| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

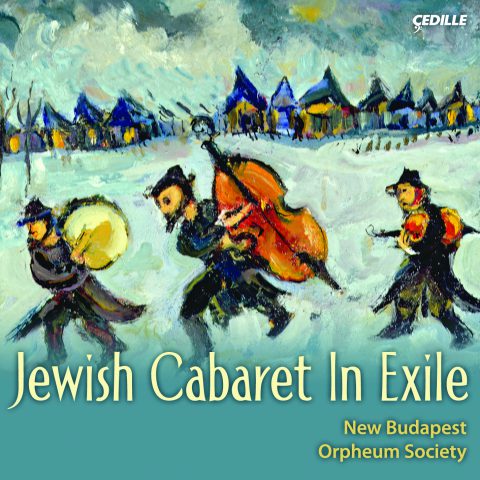

There’s more to traditional Jewish popular music than klezmer clarinet and Fiddler on the Roof. Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano revives the lively genre of Jewish cabaret and music hall songs from early twentieth-century Vienna and other vibrant centers of Jewish life.

Based on new scholarship from the University of Chicago, the CD entertains with songs of self-deprecating humor, political and cultural commentary, and social idealism (made all the more poignant by the unthinkable catastrophe soon to unfold).

You’ll discover unfamiliar works by familiar names — Weill, Milhaud, and even Schoenberg — plus gems by once-prominent songsmiths such as Friedrich Holländer, a cabaret compatriot of Weill in the intimate cellar nightspots of Weimar Germany, and the inventive and gifted Hanns Eisler, closely associated with the cutting-edge political theater of Bertolt Brecht.

The songs offer vivid storytelling set to music drawn from varied sources including waltz, tango, and jazz. Featured singers are two Chicago cantors, exuberant soprano Deborah Bard and idiomatic baritone Stewart Figa, and mezzo-soprano Julia Bentley, a sublime and highly sought interpreter of 20th century music. Cabaret-jazz accompaniment is by the (all-American) New Budapest Orpheum Society, an ensemble of violin, double bass, piano, and percussion.

Preview Excerpts

GUSTAV PICK

Anton Groiss

CARL LORENS

Viennese Broadside

ANONYMOUS

Viennese Broadside

Viennese Broadside

Carl Lorens

IRVING BERLIN

GERHARD BRONNER

ADOLF MÜLLER

FRIEDRICH HOLLÄNDER (1896–1976)

FRIEDRICH HOLLÄNDER

from Head to Toe I Am Prepared for Love

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

GUSTAV PICK

from Akiba hat recht gehabt in the repertory of the Arche Revue, an exile cabaret in New York City during World War II

HANNS EISLER

HANNS EISLER

HANNS EISLER

HANNS EISLER

HANNS EISLER

KURT WEILL

PAUL DESSAU

DARIUS MILHAUD

DARIUS MILHAUD

STEFAN WOLPE

KURT WEILL

AARON COPLAND

Artists

21: with Elizabeth Ko, flute

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDancing on the Edge of the Volcano

Notes by Philip V. Bohlman

Figure 1 – Refrain to the broadside, “Das jüdische Schaffner-Lied” – “The Jewish Conductor’s Song” – Broadside version of cabaret song, fin-de-siècle Vienna

Disembarking at Vienna’s North Train Station in the closing decades of the nineteenth century, the Jewish immigrant family to the Habsburg capital had arrived at the threshold between two worlds. There below them lay, on one side of the tracks, the Prater, Vienna’s world-renowned amusement park, seductive with its fantastic realization of multiculturalism and modernity. On the other side of the tracks stretched Vienna’s growing Jewish neighborhood, the Second District, known to the Viennese as the “Leopoldstadt” but to the new immigrants as the “Mazzesinsel,” the “Matzo Island,” in symbolic recognition of the Jewish foodways in the world from which the immigrants had just come (see, e.g., Beckermann 1984). The train trip had transported them from the lands of the Empire, which had increasingly spread across the traditional heartlands of European Judaism—Galicia, Transylvania, the Bukovina in the east; Bohemia, Moravia, the western Carpathian Mountains to the north; the Balkans to the south.

Such lands provided the landscapes for the culture of Ashkenaz, and, for those who created, sang, and heard the songs, they were very real places indeed. Großwardein in the song, for example, was the German name of the western Romanian city of Oradea. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire it also bore the Hungarian name, Nagysvarad, not least because its population was officially Hungarian-speaking. At times 70% Jewish in the century prior to the Holocaust, Großwardein also contained a substantial Yiddish-speaking population. Tarnow was the German name for Trnva, today in Slovakia, but from the Middle Ages to the modern era a center of Jewish art and music, for example, a school of Passover haggada illustration and a tradition of training cantors. For the audiences hearing “The Jewish Conductor’s Song” in fin-de-siècle Vienna, Großwardein and Tarnow symbolized Jewish tradition writ large across the face of empire.

The two sides of the railroad track were no less real, and they presented the new immigrants with tough decisions, indeed, decisions that would become no easier as they settled in Vienna and charted their individual destinies across its cosmopolitan landscapes. Did one opt for tradition, that is, the seemingly familiar Jewish world of the Leopoldstadt, which substituted the urban ghetto for the rural shtettl? Or did one abandon oneself to the dizzying fantasy of the Prater, which in its own way was also a metaphor for an Empire that distinguished itself by embracing, even absorbing, difference through experiments in the arts, the sciences, and the human mores that forged the path of modernism?

These are the questions that we encounter in the cabaret and popular songs on the CD, Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano. Jewish cabaret took the dilemma of the Jewish immigrant to the metropole seriously, which is to say, seriously enough to poke fun at the dilemma in just about every way the songsmiths and musicians of fin-de-siècle Vienna could imagine. Jewish cabaret, too, was an immigrant tradition, and not surprisingly it accompanied the Jewish immigrants who traveled to the Habsburg capital in search of opportunity. Rooted in the narrative and theatrical traditions of Eastern Europe Yiddish culture, Jewish cabaret found new soil in the city. Seasonal folk–song repertories, say, those performed in a shtettl for Purim, absorbed new themes and took advantage of the transition from oral to written transmission. The Jewish instrumental music of the country—klezmer, but much, much more—similarly became urbanized, not least because musicians turned to professional opportunities they could never have known before. It was all very dizzying. The world around the immigrants changed more quickly than they could possibly have imagined, even from the train bearing them to Vienna.

The question still remained, not unlike the question posed to the train conductor by the kosher kid in the “The Jewish Conductor’s Song” of Figure 1: “Oh, dear conductor, what have you done?” Maybe the train really was headed in the wrong direction after all. In the end, the kosher kid might indeed be out of luck in Vienna. That question, in subtle and not-so-subtle variants, also finds its way into almost every song on this CD. And it was the challenge to respond to, if not answer, the question that led Europe’s Jews toward the edge of the volcano that these songs increasingly represented during the course of the early twentieth century.

The Many Worlds of Jewish Cabaret

Jewish cabaret and popular music mirrored the complex circumstances that accompanied the growing confrontation between traditional Jewish culture and the modern world. That confrontation occurred in many places, which together engendered the modernism that challenged and enveloped Jewish music and culture. That it really was a matter of “place” is revealed in the songs of the Jewish popular stage, for they consciously employ geographical references that are, on one hand, specific while, on the other, often imaginary if not rich in fantasy. The life-transforming detour in “The Jewish Conductor’s Song” might simply have referred to East and West, or even more suggestive terminology, such as shtetl and ghetto, but instead we know that the trains of the misadventure traveled along routes from Vienna to Tarnow to Großwardein.

In most of the songs on this CD, in fact, the poets and lyricists who wrote their texts provide us with specific places to chart what amounts to a map of the worlds of modernity. As specific as such places were—for example, the Viennese streets and districts in the several versions of the “Jewish Coachman’s Song,” or the kibbutzim in Kurt Weill’s “Ba’a m’nucha”—they were also imbued with the power to convey meaning through stereotype. And this is where the stage tradition really entered the popular-song scene, for it was on the stage itself that Großwardein or Vienna acquire diverse and cosmopolitan Jewish populations. When it reaches the stage, a song invokes a distinctive world, which we might even call a microcosm that itself sets a further stage on which encounter and confrontation take place.

If they were to have meaning for their audiences, the songs had to stage worlds that were both familiar and unfamiliar, which is to say modern in some unexpected way. While listening to these songs, indeed, it is important to keep in mind that they were produced intentionally with the audience in mind. They needed to grab the audience’s attention, usually by transporting them to worlds in which the familiar and unfamiliar were juxtaposed. Most songs, therefore, contained specific references to both East and West, the two larger worlds of Ashkenazic Jewry from which the cabaret audiences came. East and West were, in fact, crucial themes in the discourse of Jewish modernism, particularly at the turn of the century, when attempts to bridge the differences between the two found their way into popular and scholarly literature, and popular and serious musical practices.

There was, in fact, nothing subtle about the attempts to find common ground between Yiddish-speaking Jews of the East with German-speaking Jews of the West (see Aschheim 1982). We find cabaret songs, for example, with titles like “Der Vergleich zwischen den deutschen und polnischen Juden” (“The Comparison of the German and Polish Jews,” performed in fin-de-siècle Vienna by the well-known duo, Emil Schnabl and Eduard Blum (see Bohlman 1994: 442). The coupling of East and West found its way into the titles of books, pamphlets, and journals, such as the literary journal, Ost und West, which was published in Berlin from 1901 to 1923 (see Brenner 1998). Jewish intellectuals and writers embraced the dual theme of East and West, not least among them the religious philosopher, Martin Buber, and the novelist, Joseph Roth.

Most important for the musical streams that emptied into the cabaret repertories, the folk song of the Eastern Jews—the Ostjuden, as they came universally to be called—captured the fancy of Jews in Central Europe, whether the secular and religious social organizations of various kinds, or the burgeoning publishing industry dedicated to make Jewish secular music available to a modernizing Jewish public. From the turn of the century until the late 1930s, an overwhelming majority of Jewish folk-song anthologies appeared and increased their girth by absorbing songs in Yiddish from the East. Many Jewish songbooks, moreover, wore their easternness on their sleeves by employing titles such as Ostjüdische Volkslieder, “Folk Songs of the Eastern Jews” (Eliasberg 1918). The songbooks, however, did not simply import songs from the East, rather they provided transliterations and translations of the Yiddish into German, thus inventing—or reinventing—a previously non-existent folk-song repertory for the cosmopolitan Jews of Central Europe (see Bohlman 1989a: 47-78).

The worlds of Jewish popular and cabaret song, however, exposed even more complex confrontations between tradition and modernity. One of the most common of all juxtapositions placed the shtetl side-by-side with the ghetto. The shtetl—Yiddish for “little city,” but referring to the isolated Jewish village—embodied the world of traditional Jewish culture, symbolized by orthodox and hassidic customs, and by the Yiddish language. The ghetto—a term originally referring to the Jewish quarter of Renaissance Venice—was the urban Jewish community that straddled the boundaries between Jewish and non-Jewish worlds. Both geographical images appeared in the popular songs, serving as an index to the transformations of Jewish culture along the journey from tradition to modernity. The songs not only rendered the shtetl and the ghetto with vivid imagery, but they placed diverse Jewish communities in the shtetl and ghetto, effectively bringing them together on the stage, but also providing a mirror for the audiences, which too had roots in the shtetl but found itself occupying the ghetto on the long journey to a fuller existence in the modern world of the metropole.

As sharply as the cabaret stage portrayed these different worlds, the border between the stage and the audience, in other words, the very edge of the stage itself, was indistinct, if not actually blurred. The edge of the stage might well be confused with a mirror, in which the audience saw itself, recognizing the familiar and the unfamiliar as they played out in the songs and skits of the stage. Some would recognize themselves in a song unfolding along a rags-to-riches trajectory; others might see their neighbors from the old days in the shtetl; still others might wonder if a new song was meant to be quite as personal as they found it to be. The worlds of the cabaret stage did not stop and start at the edge of the stage. They flowed across it and thus also flowed together, making the confrontation between tradition and reality more real and more fantastic. And ultimately, by the 1930s, more tragic too.

Form, Function, Genre

Cabaret was not a genre of music theater in itself, but rather a loose collection of skits, monologues, and poems, into which were mixed sundry musical acts ranging from the folklike to the popular. An evening of cabaret unfolded as one actor or singer, or ensemble with singers and actors, took to the stage to perform. An evening of cabaret might hang together because the diverse acts contained some elements of a common theme, perhaps from the cabaret itself or a few notable performers associated with certain types of acts. There were comic-singers (Gesangskomiker), those known best for singing Couplets, and others who concentrated on political topics or preferred to stick close to more serious themes, as in the literary and socialist cabarets (see Scheu 1977). Because the characters who appeared on the cabaret stage were usually stock figures, individual actors and singers often acquired fame by playing one type of stock figure or another, demonstrating a malleability that also allowed them to move from one stage to another, not just at Jewish cabarets but also at non-Jewish and topical cabarets, as well as other settings for the musical stage, from Yiddish theater to the operetta (see, e.g., Dalinger 1998 and Czáky 1996).

Lyrics and musical style, too, might display some attempt at unity, but more often than not diversity, which is to say mishmash, was the rule rather than the exception. Mishmash, however, was not simply the random product of mixing different repertories and styles. Quite the contrary, cabaret arrangers and the directors of cabaret ensembles seized on the qualities that were inherent in mixed programs and transformed them into hybrid forms. Individual medleys (e.g., “. . . To Großwardein” on this CD) were styled as potpourris. The insertion of instrumental interludes between songs and skits, too, created an overall impression of potpourri, in which one act gave way to the next, sometimes with the seams smoothed over, often not.

The songs of the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft were sometimes big hits, usually not, even though they were one of the best of all Jewish cabarets, surviving through the 1920s and into the 1930s, even as the specter of the Holocaust loomed more menacingly. The biggest hit for the Budapesters was a skit about a card game, Adolf Bergmann’s Klabriaspartie, “The Sheepshead Game,” which was actually a series of skits played out by actors on the stage playing cards (see Rösler 1991: 56-59). “Klabrias” may or may not lend itself to translation as “sheepshead,” probably the closest North American equivalent, but the persistence of the name itself symbolizes the catalytic role of the skits, which appeared first on the Jewish cabaret stage and then spread to other Viennese cabarets, where under the same name it became a standard opening act. “Klabrias” became one of many Yiddish words that entered Viennese dialect and German, mediated in this case by the popularity of cabaret. The skits and monologues of the Klabriaspartie were themselves like a card game, constantly shuffled, with songs thrown in, among them Gestanzeln, traditional four-line stanzas that allowed the singers to poke fun at everyone and everything, and to play with words and melodies as if they were individual hands waiting to be dealt in rapid succession.

For the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft the cabaret evening started with the Klabriaspartie, and it is hardly surprising that the card-games-cum-skits became so famous that many versions survived in printed forms. The card players took to the stage as if it were the world, and in Yiddish and Viennese dialect, they shaped that world as they wanted, even when that meant dealing an extra card, or betting more than they had in their pockets. Just a taste of the Budapester’s signature skit follows:

Werde jetzt’n G’stanzeln singen,

Tei ti ti to! Tei ti ti to!

Möchte Si zum Lachen bringen,

Tei ti ti, ti ti to!

Sollte mir das nicht gelingen – ach waih!

Dann soll’n Se zerspringen!

I’m going to sing G’stanzeln now,

Tei ti ti to! Tei ti ti to!

I want to make you laugh,

Tei ti ti, ti ti to!

If I don’t succeed at that – ach vey!

Then you’ll fall into pieces!

The different skits, or “stanzas” of the game took aim at specific individuals or stereotypes in Viennese Jewish society. A g’stanzel like the following took on religion and rabbis, recognizing at the same time that Jewish life in the metropole had become increasingly secular:

Ein Rabbiner that in’ Tempel gehen,

Er wollte fromme Juden sehen,

Heraus kam er mit böser Min’ – ach waih!

Er war Kaner d’rin’.

A rabbi went to temple,

He wanted to see observant Jews,

He left with a bad temper – ach vey!

There was nobody inside.

Politics, too, ran through the stanzas and the skits, providing the Jewish audiences an opportunity to laugh openly about the anti-Semitism that afflicted them, especially during the many years when Karl Lueger served as mayor of Vienna.

Es kaufte e Jud’ e alte Hosen,

Ä Paraplüi, ä Zuckerdos’n,

Kurz, alles kauft er, was er sieht – ach waih!

Nur an’ Lueger kauft er nicht.

A Jew bought an old pair of pants,

An umbrella, a package of sweets,

In short, he bought everything he saw – ach vey!

Only he didn’t buy anything from Lueger.

The members of the audience—a mixture of new and old immigrants to Vienna, of working and middle class, of observant and assimilated urban dwellers—were meant to see themselves and their own confrontation with modernity in the card game. The struggle to survive, in other words to make a living in the metropole, took center stage as the game wound down, and to bring it closer to home, Simon Dalles, the stock character who was the allegorical and literal (dalles means “poverty” in Yiddish) representative of poverty, would sing:

Simon Dalles:

Das Klabrias, das Klabrias,

Das ist mein ganzes Leben.

E Dadel geb’ ich nix eher

Far e Barches mit Zibeben.

De Karten können meine Frau

In größten Zorn oft bringen.

Ich glaub’, sie wird vor Gift und Gall

Noch einmal gar zerspringen.

Ich mach’ mir aber gar nix d’raus,

Denn ich heiß’ Simon Dalles.

[:Das Klabrias, das Klabrias,

Ist auf der Welt mein Alles.:]

Simon Dalles:

Sheepshead, sheepshead,

That’s everything in life for me.

I’d rather play a hand

Than eat chala on Shabbas.

The cards often bring

My wife’s wrath down upon me.

Seems to me she’ll explode again

From all that bile and poison.

But that doesn’t bother me,

Because my name is Simon Dalles.

[:Sheepshead, sheepshead,

It’s everything in the world for me:]

Couplets, Contrafacts, and Covers—The Music of Jewish Cabaret

Musicians and actors collaborated to perform Jewish popular music long before we have specific records of their identities. Among the first musicians were no doubt the forerunners of what we today call klezmer musicians, and chief among the actors were probably the traditional wedding and festival merrymakers, the badkhanim. Both klezmorim and badkhanim were professionals at least as early as the seventeenth century, and as professionals they moved from community to community, already negotiating the boundaries between the traditional private sphere and the public spaces of an emerging modernity. Even during the Middle Ages, moreover, it is the popular Jewish musician who finds his or her way into the public record and therefore symbolizes the transformation of Jewish musical traditions from sacred, private, and communal to secular, public, and cosmopolitan.

We know about these popular musicians because they were professionals, in other words, because they were paid money and records of payments to them were made. Under various guises, Jewish popular musicians appear in records as early as the thirteenth century, where Walter Salmen has uncovered substantial evidence for their activities in the Rhineland, that is, in the main centers of the Holy Roman Empire, such as Mainz, Speyer, and, above all, Worms, all cathedral towns with large Jewish populations (see Salmen 1991). In other areas of intensive Jewish settlement, such as Burgenland, the border area today shared by Austria and Hungary, but home since the fifteenth century to the sheva kehillot, or “Seven Holy Cities” of the Jews, Jewish instrumentalist were apparently active even during the threat from the Ottoman Empire during the seventeenth century. Combing the tax rolls of the Hungarian capital of the area, Sopron/Ödenburg, for evidence of Jewish music-making during allowed me to find frequent payments from musici (pl. for the Latin musicus, “musician”), obviously the local instrumental musicians who were distinguished from the singers of vocal music, cantus, no doubt the Jewish cantor or hazzan.

Printed broadsides also provide considerable evidence of popular music in early modern Europe. Among the very first printed versions of ballads and other popular songs in the fifteenth century, for example, were songs printed by Jewish printers and intended for Jewish consumption, a fact made clear not only because they were printed in Hebrew characters, even when in a German dialect, and they might eliminate specifically Christian references. Music and text for the well-known German ballad, “The Count of Rome,” found its way into early modern popular tradition in precisely this way, appearing first as a printed melody in 1510, but then a text with Hebrew characters around 1600, which survives as the earliest extant version (Bohlman and Holzapfel 2001: 90-102).

The publication and dissemination of early modern Jewish ballads were similar in almost every way to the use of broadsides to popularize Jewish cabaret songs in fin-de-siècle Vienna three centuries later. Jewish popular musicians appear in both expected and unexpected places during the centuries stretching from early modern to modern Europe. One of the most common places to find them depicted visually was in drawings of weddings, where the distinction between badkhanim and klezmorim becomes increasingly evident. Popular music, we might imagine from the numerous etchings and drawings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was parsed into different repertories, for which different musicians—soloists and ensembles—were responsible. There was a division of labor, which in turn required specialized knowledge and musical skills. It is hardly surprising, then, that the popular musicians we encounter first in the nineteenth century possessed an impressive range of skills.

The first popular musicians to whom a measure of visibility and even fame accrued during the nineteenth century began their careers as traditional performers in Eastern Europe and then succeeded in winning over audiences in Central Europe by the mid-nineteenth century. The “Broder Singer” were a troupe from Brody, in Galizia, then a province in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today a region in western Ukraine. The milieu for the Broder Singer was the café and the inn, and they took their skits, monologues, and songs on the road to Poland, Romania, and Russia. Until the 1860s, they were the model for all aspiring Jewish popular musicians and actors. From the 1860s until the end of the nineteenth century, that mantle was taken over by the “Herrenfeld Brothers,” a theatrical troupe from Russia, which extended its tours increasingly into East-Central and Central Europe. In the early 1880s, the repertories of the Herrenfeld Brothers were so well known that they were gathered in 1888 as an anthology, which today stands as the earliest surviving publication of Yiddish songs (see Dalman 1891).

Jewish popular musicians were mobile, traveling especially from the provinces to the metropole; it was, therefore, the newly forming outer districts that became the entrepôt for the musicians and audiences who translated the traditional and provincial into the modern and urban. Theaters and dance halls of all kinds sprouted up on the outskirts of European cities in the second half of the nineteenth century, serving particularly the entertainment needs of a new bourgeoisie, within which growing Jewish middle and upper-middle classes were increasingly visible. In Vienna, the stages of the so-called Vorstadt—best translated as “edge of town” until the twentieth century—were laboratories for popular music. It was on the stages of the Vorstadt, for example, that the hit quartet of late nineteenth-century Vienna, the Schrammel Quartett (listen to the fourth verse of the “Viennese Coachman’s Song”) had its start, and where dialect songs mixed, matched, and poked fun at the languages spoken by the new immigrants. The stage of the outer districts also provided a venue for new acts to start out, or for new songs to survive or fall victim to the first waves of critical response.

The suburban theaters and dancehalls were home to the couplet, a genre of popular song characterized by its mobility and flexibility. Singers and actors could take couplets with them, inserting them in just about any skit and making a few quick adjustments to their texts so that they would appeal to any audience. Couplets fitted the performative needs of the cabaret stage perfectly, and the historical trajectory of the couplet from the urban periphery to its center narrates the history of the cabaret from the late nineteenth century until the 1920s. The couplet variously detailed, criticized, or simply made fun of the social pretentions of the very audiences that were listening to it and watching the skits and monologues it accompanied. The cabaret tightened the interrelations among these popular performance genres, heightening and politicizing its critique.

The broadsides, couplets, and parody songs that form the first group of songs for Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano grew from and served as symbols for the modern, cosmopolitan European city, whose cultural profile after 1850 increasingly bore witness to the influx of minorities and cultural Others, not least among them Jews from the rural regions and shtetls of Eastern Europe. Couplets and cabaret were among the modern products of this city music culture, “modern” because because the songs themselves were produced—or more precisely, reproduced—using the machines of modernity, such as the printing press, and because the song texts addressed the conditions of modernity, especially the confrontation of the individual with a society undergoing rapid, usually disjunct change.

When couplets first began to appear on the city soundscapes of Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, they were already something other than folk songs, but because of their own rapid change and often ephemeral lives, they were also not, strictly speaking, popular songs. They came into existence in a cultural domain between the folk and the popular, depending on both but fully participating in the musical life of neither. The melodies, for example, had to be familiar, if not well known, and it is for that reason that they drew frequently from folk-song repertories, which were their musical common culture. The mechanical reproduction of couplets, however, made it possible to juxtapose a wide variety of disparate symbols from an urbanized popular culture, which, while not a musical common culture, provided a set of experiences that life in the city rendered as common.

Just as Jewish couplets negotiated a space between folk and popular traditions, so, too, did they depend not only on the growing presence of Jews as Viennese musicians and consuming publics, but also on the reaction of non-Jews to the transformation of Vienna effected by a growing Jewish population. Jewish couplets, therefore, were often about the relation between Jews and non-Jews, and the dynamic shaping of the modern city that this relation engendered.

Once established in the metropole, Jewish cabaret musicians sought to achieve greater musical sophistication, which might well also provide the key for more success on the stage in general, especially if the musical stages in the middle of the city were willing to extend opportunities to them. By no means were even the earliest musicians folk musicians in any traditional sense, but rather they demonstrated great prowess to move from genre to genre, repertory to repertory. The parody of cabaret traditions frequently depended on an ability to juxtapose country and city traditions, for example, to transform scenes from operas, especially Italian operas, into folklike skits that gained a considerable measure of humor because the parts were not supposed to fit together. Scenes from operas such as Verdi’s Nabucco, for instance, found their way into the Jewish cabaret repertory because they provided a representational template for the East and the historical past of the Jewish people. Serious art song, too, was not immune from the attack of cabaret parodies (see, e.g., Kabarettisten singen Klassiker 1988). Both audiences and musicians, the repertories of the most popular Jewish cabarets, such as the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft, possessed considerable musical sophistication. That sophistication surfaces again and again in the songs of Dancing on the Edge of the Volcano, from unexpected musicians, such as Arnold Schoenberg, as well as professionals, such as Friedrich Holländer, who made their careers by knowing the stage intimately.

The Jewish cabaret formed at the convergence of a musical tradition based on couplet-singing and of a theatrical tradition arriving with theater troupes from Eastern Europe. The cabaret embodied many different genres of popular song and entertainment, which together made it possible to move deftly through various forms and degrees of cultural and political critique. Music, because of its capacity to bear multiple meanings—its semiotic slipperiness—enhanced and particularized the many forms and genres of song and theater, allowing for the formation of cabarets that served specific constituencies—poets and modernist artists, for example, in Berlin’s Literary Cabaret—and that juxtaposed social issues, as in the substantial number of socialist cabarets, especially during the 1920s and 1930s. The distinction between themes and genres in Jewish cabarets that were political and those that were socialist or even Zionist, therefore, proved not to be very great at all. For these reasons, the cabaret attracted Jewish writers, critics, intellectuals, and musicians such as Karl Kraus, Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler, and Arnold Schoenberg, works by all of whom appear on Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano.

The cosmopolitan character of Jewish cabaret and popular song notwithstanding, the traditional always breaks through in poignant and powerful ways. The most socially critical songs intentionally employ texts in dialect; the loss of folk and religious traditions of the past is at once mocked but mourned with a cloying nostalgia; and the instrumental sounds that mark a repertory as Jewish are worked into new arrangements in order to hold on to the past. At any one moment of performance and in any single repertory, Jewish popular music achieves its power and meaning because of the multiple genres that it consolidates. There was, indeed, a common denominator: the Jewishness of songs chronicling the confrontation of tradition and modernity, and presaging an impending specter of crisis.

The Public Face of Popular Music and the Paradox of Stereotype

Jewish popular song depended on the interplay of image and stereotype. As a musical genre that needed to capture the public’s attention immediately, whether from the printed page or from the stage, popular song relied on a vocabulary that was familiar and accessible. The humor in its texts was not subtle, rather direct and often vulgar. Social critique, in and of itself, did not make a hit, but when it poked fun or stripped its victims of their respectability, it often did make a hit. The music of popular song, too, depended on stereotype. Because these songs plied the borders between oral and written traditions, they relied on melodies that were familiar to everyone, not just a single community. Still, when attempting to broaden that community and to expand the audience for Jewish popular song, it was necessary to create and canonize stereotype, in other words, to make a song “sound Jewish,” which is what Hermann Rosenzweig does in “. . . To Großwardein” by using a potpourri of melodic fragments that many listeners to Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano will imagine they have “heard before.” In fact, they have.

By the end of the nineteenth century the face of Jewish public culture, which it displayed as self-identity to the outside, increasingly depended on standardized images. The fundamental axis for the standardization of the public face was that of East vs. West. As Jewish communities entered the public sphere of Western cosmopolitan culture, they often chose to display Easternness. The construction of synagogues to look like Moorish mosques, covered with arabesque, inside and outside, is probably the most familiar example, even in the United States, where mosque-like synagogues were also built in large numbers at the end of the nineteenth century. The same architectural style was employed for the major synagogues of many of Europe’s biggest and most important synagogues (e.g., Europe’s largest synagogue, the Dohány Street Synagogue in Budapest, and Berlin’s largest synagogue, the Oranienburgerstraße Synagogue), precisely at an historical moment they were including mixed choruses and proudly building organs.

Jewish popular music underwent complex processes of orientalism. The East signified the traditional world, be it the East in which Yiddish was spoken, or be it the East (mizrakh) of Jerusalem, to which the synagogue was oriented. The play and interplay of images and melodies signifying the East overflow especially in Hermann Rosenzweig and Anton Groiss’s “. . . To Großwardein,” the cover of which illustrates this CD booklet. For the cosmopolitan public of Budapest and Vienna, Großwardein was the East, geographically and literally at the eastern edge of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The stage on the cover of the sheet music, persumably that of the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft, included a group of dancing hassidic Jews, stereotyped images of the world of Eastern European Jewry. Behind them, however, is another image of the East, this time a city in the Eastern Mediterranean, framed by palm trees and replete with mosques and minarets. Alone, these images are not completely meaningful, but when they are juxtaposed, which is also what the potpourri style in the music achieves, they pose questions about the ways in which changing Jewish identities contrast and conflict with modernity.

Insert near here – Cover of “. . . Nach Großwardein”

The boundaries between images and sounds that encode Jewishness and those that rely on codes of anti-Semitism are often blurring and all-too-often non-existent. There are moments even in the texts of several songs in Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano where stereotype produces images that are easily lend themselves to being read as offensive. The codes of anti-Semitism, thus, became even more complex when imported into Jewish popular-song traditions through the stocks of image and stereotype. Quite commonly, Jewish popular songs intended for German and Austrian urban audiences made fun of Eastern European Jews trying to find their way in the big city. Anti-Semitic songs often employed the same theme, but in these songs directed toward a non-Jewish public, all Jews trying to find their way in the metropolis came from the shtetls of Eastern Europe.

The song genres in cabaret and parody depended extensively on the potential of making fun of others. This was how contrafact and parody worked when it worked at all. Dialect songs and the right mixtures of Yiddish and hassidic dances were crucial to the meanings that popular song could communicate. Musicians and actors, therefore, needed to develop stores of Yiddish words and phrases, and of melodic fragments that made their songs sound Jewish, but not too Jewish, which is to say not so Jewish as to contain an unrecognizable set of symbols.

The technologies of popular-music reproduction also bear responsibility for the stylization and trafficking of stereotype. Broadside printers, such as Carl Fritz, who printed several of the broadsides used as sources for the repertory of the New Budapest Orpheum Society, would employ the same illustrations again and again. We can trace the images of observant Jews or coachmen or, for that matter, schlemiels as they move from broadside to broadside. Melodic fragments, too, are reduced to the bare minimum, often to a few phrases, and used as often as possible, with or without particular sensitivity to their appropriateness. Such technologically reproduced images were, nonetheless, appropriate when they reflected the trafficking of images on the cabaret stage, where actors and singers relied on their audiences’ ability to recognize the images. It is perhaps for such reasons that the stereotyped images are depicted on the printed music itself as if they were on the stage, from which they turned their faces to publics who were both literally and figuratively present.

Jewish Cabaret and the Landscape of the Metropole

The epicenter of the Jewish cabaret scene in Vienna, the Second District, or Leopoldstadt, was also one of the most multiethnic and rapidly changing quarters of the city. Its main streets radiated out from the Vienna North Train Station, the point of debarcation for the in-migration of Jews, but also of Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ukrainians, indeed, just about anyone coming to the capital of the Habsburg Monarchy from its northern and eastern provinces. The Second District was the center of popular entertainment in the changing metropolis, the Prater, recognizable for many readers because of the massive ferris wheel that has come to symbolize it. The popular music of the Second District not only took the multicultural and multireligious character of the quarter as its point of departure, it moved across the landscape of cultural difference with a dynamics dependent on each group’s willingness to laugh at itself and its neighbors. Within the Second District itself there was even a dynamic sense of transmission and shifting repertories, for example, when cabaret ensembles such as the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft would offer one set of performances on their home stage, originally the Hotel Schwarzer Adler, and then appear for some guest performances at one of the many stages in the Prater amusement park. At the Hotel Schwarzer Adler, they played to unsre Leut, “our own people,” whereas in the Prater they played for a mixed ethnic audience and for the mixture of classes that frequented the amusement park.

The density of Jewish stages in the Second District notwithstanding—there were eight that held regular performances by ca. 1900, with others offering a less regular fare—Jewish cabaret rubbed elbows with the popular entertainments of other ethnic groups. Songs and singers, actors and satires, moved from troupe to troupe, from one side of the city to the other. Mobility of repertory and changeability of audiences were both crucial factors in the shaping of cabaret traditions, and it was essential for the best cabarets to respond to all these factors with appropriate adaptability. The best troupes were careful not to remain only in the Second District, and they made sure that they varied their repertories sufficiently not to be stereotyped only as Jewish. This meant incorporating dialect songs that attracted several ethnic groups and a mainstream Viennese population. It also required that the troupe be mobile enough to make guest appearances in other city and suburban areas, and to go on tour beyond the city’s borders on occasion. At all such venues, the best cabaret troupes were sensitive to the cultural and linguistic differences, and they turned such differences to their advantage, absorbing new songs and acts, and adapting new versions of more standard fare.

Ethnic difference was not the only factor upon which cabaret played. Amost as important—and surely more so at moments of crisis, such as the inflationary years of the 1920s and early 1930s—was the impact of socioeconomic factors and class distinctions. It is impossible not to notice that class is one of the most central themes running through the songs on this CD. The narrators in the several coachman songs sing with pride of their success as working-class heroes, all the while looking over their shoulders at the wealthy passengers in the coaches, whose lives may not be as admirable as many might imagine. The several songs that trace the careers of immigrant Jews from Eastern Europe to the metropole also fix their critical gaze on class, particularly the spectacular rise from innocence (Eastern European traditional culture) to ill-gained fortunes (cosmopolitan assimilation). Class differences are also stereotyped as intraethnic differences, above all when distinguishing between Eastern European, Yiddish-speaking Jews and Central European, German-speaking Jews. The two Jewish groups pursue entirely different occupations in the songs, producing easily recognizable caricatures in text and melody, as well as the costumes worn by the cabaret actors playing the stereotyped roles in the songs.

Gender differences, too, appear again and again in the songs of the cabaret stage. The folk and folklike repertories from which many broadside ballads came commonly included repertories of songs with texts that reflected the feminine ideals of family and tradition. The predominance in some areas of songs about the travails faced by women, no doubt borrowing extensively from Yiddish folk song, suggests that women’s issues found their way to popular singing traditions that remained more or less isolated in the Jewish community (Bohlman 1989b). Once the broadside traditions hit the cabaret stage, however, they had entered the public sphere, and it was there that an entirely new set of stereotypes accrued to them. Women still anchored the traditional pole of the social continuum, symbolizing as often as possible the family as a cultural and religious cornerstone. Women appear also as victims of violence, less so in the cabaret than on other popular stages. By the 1920s and 1930s, with the collapse of imperial Germany and Austria, and the subsequent rise of fascism and anti-Semitism, women occupy new roles in the political songs reaching the popular stage, roles we witness vividly in the songs by Hanns Eisler: those most affected by the destruction of traditional Jewish culture.

The Jewish cabaret provided a stage that allowed spectators to see themselves in the guise of others. The audiences recognized themselves, but just barely; indeed, the scenes and couplets on the stage narrated the familiarity of a world the audiences had once known, but now had become foreign. Cabaret allowed musicians, actors, and audiences to pick and choose, and ultimately to assemble their own images of the popular against the backdrop of modernism. For these reasons, the cabaret had a seductive attraction for diverse audiences, but also for modernist composers, such as Arnold Schoenberg, who wrote several sets of songs for the “Überbrettl” cabaret at which he played.

Jewish cabaret would survive World War I, and it would thrive again in the 1920s and 1930s, when it proliferated and assumed new forms, especially the political and socialist cabaret. In Vienna it was only a short distance for Jewish cabaret performers from the socialist cabaret to the Marxist cabaret and, following a different trajectory, to Zionist cabaret. Hanns Eisler, Bertolt Brecht, and Kurt Weill all recognized the expressive opportunities that such cabarets opened for their political songs. More tragically, it was also but a short distance from Jewish cabaret to the cabaret of the Holocaust, such as the stages in the Jewish ghettos of Poland or in the concentration camps (see, e.g., Migdal 1986). The cabaret of the Holocaust brought the traditions of Jewish popular music could no longer be restrained at the edge of the volcano.

The Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft—Then and Now

“Was gibt es Neues—What’s New?”

The Pester Orpheum-Gesellschaft in Vienna. The well-known musical stage director, Lautzky, has engaged the members of the Budapester Orpheum, and those same members, under the direction of J. Modl, will make a brief guest appearance here in Vienna. The Society can point to a number of different players and musicians, which are particularly beloved in the Hungarian capital; among the members are the Württemberg Sisters and the Duo Singers Rott, and thus there can be no doubt that they will quickly conquer the Viennese public. For the first time ever, on Thursday, June 27th, the guests from Budapest will appear at the Hotel “Zum schwarzen Adler” on Tabor Street, where they will present a very interesting program.

Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt, June 27, 1889, page 9

With the appearance of the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft in early summer 1889, the world of cabaret in Vienna changed forever. The Budapesters really did burst upon the cabaret scene, transforming Vienna’s culture of music and entertainment as if a revolution had been waiting to happen. The announcement above might seem innocent enough, buried as it was inside the pages of Vienna’s most widely distributed arts and entertainment newspaper. The announcement states clearly that the Budapesters had arrived for a “guest performance”—a Gastspiel—and a short one at that, but before the summer had passed, it was evident that the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft truly had fulfilled the prediction that it would “conquer” the Viennese public. In that first summer of 1889, the troupe would perform at several venues in the Leopoldstadt, as well as in the newly integrated suburbs, such as Hernals (today the Seventeenth District of Vienna), but by the end of the summer, it was the venue for their very first performance, the Hotel Schwarzer Adler—the Black Eagle Hotel—that would provide them a stage to call their own for the next seven years. It was on that stage that the Budapesters would not just conquer the Viennese public, but would lay the very foundations for Jewish cabaret in fin-de-siècle Central Europe and beyond (Wacks 1999).

Why were the contributions of the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft so revolutionary? Were they somehow the first troupe to consolidate a modern Jewish cabaret tradition? Did they appear at just the right moment in the history of Jewish modernism in Vienna, on the eve of the outbreak of a new wave of anti-Semitism, but also at a moment when many professional and cultural boundaries between the Jewish community and the public sphere were being broached? To all these questions one has to answer both “yes” and “no.” The Budapesters entered a popular music and stage scene that was clearly primed for their appearances in the summer of 1889. Perhaps more than they themselvees had expected, they received an increasing number of invitations for guest performances, so that by summer’s end they were playing on some stage in the metropole every night.

The Budapesters became so visible so quickly, that they had no choice but to respond to their rising fame by unleashing a remarkable creativity. From early programs, from early advertisements and announcements in the entertainment media, not just the Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt but the Wiener Vergnügungs Anzeiger, and from the public censors’ records approving or rejecting new songs and plays proposed by the troupe, we know that the Budapesters were constantly changing and expanding their repertories into many directions. In a word, they seized upon the success they encountered in Vienna. As we follow their successes in the entertainment media, we recognize that they took their initial potpourri of a songs, operetta arias, skits, and satires, and transformed them into longer, well integrated forms and genres. Skits, for example, became one-act plays. The Gestanzeln, or additive stanzaic songs they borrowed from Austrian folk song, were woven into larger improvisatory genres, not least among them their signature work, the Klabriaspartei. Not surprisingly, they attracted the best singers and actors from Vienna, its outlying districts, and the rapidly growing cosmopolitan culture of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Their successes were so remarkable that, by 1913, they no longer needed to appear on the stages of hotels or small theaters, but they could claim a hall near the Prater amusement park (Praterstraße 25) as their own.

During the 1890s the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft came to play a foundational role in the cosmopolitan popular culture of fin-de-siècle Vienna. It may well not be an exaggeration to say that everyone in Vienna knew who they were and what their repertory was. Distinguishing the thirty-year career of the Budapesters was their preference to claim one stage as their “home,” but then to perform at other venues, both in the Jewish Leopoldstadt and in Vienna’s central and peripheral districts.

1889-1896 – Hotel Schwarzer Adler

1896-1903 – Hotel Stephanie

1903-1912 – Hotel Central

1913-1919 – Praterstraße 25

The permanence of such halls allowed them to adopt and adapt different programs, to build their stock of performances, and to respond differently even to the varying degrees of tolerance that characterized the different parts of the city. Depending on where they played, their programs might be more or less “Jewish.” In the Leopoldstadt, where all four of their home stages were located, they could employ a much more varied use of Jargon, texts in Yiddish or with Yiddish words, or songs that were gejiddelt, sung, that is, with the characteristic markers of Eastern European Jewish vernacular speech. Press announcements and reviews often referred to the Budapester as a Singspielhalle, literally a “hall for musical theater,” but in fact a designation that the ensemble was mobile and that it could “take the show on the road” (Wacks 1999: 14-16).

The Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft disappeared from Vienna’s cabaret scene in the summer of 1919 almost as suddenly as it had appeared forty years earlier. World War I had taken an enormous toll on the musical and popular culture of Vienna, and the Budapesters’ own demise in some ways paralleled that of the multicultural empire and cosmopolitan city that produced them. Just as they had constantly and consciously transformed their programs and identity as a cabaret troupe in fin-de-siècle Vienna, so too did they introduce seemingly deliberate changes into their performances during World War I. On one hand, their musical performances became more substantial and required larger performing forces. Several operettas by the great composer for the musical stage, Robert Stolz, among them some premières, appear in the wartime announcements. Their own “house composer,” Alexander Trebitsch, also created several significant new works for the company during the war. On the other hand, the theatrical side of the programs veered sharply toward comedy, with single Possen, or satires, laced through an evening’s performance. As substantial as the programming was, it departed from the Budapesters’ stock in trade, and in so doing it may well also have caused them to abandon the cabaret stage.

On May 1, 1919 the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft announced that its performance in the hall on the Praterstraße that had been its home since 1913 would be its “Farewell Performance,” and that the troupe would play the Klabriaspartei for the “1900th and final time.” As it had in June 1889, the Budapesters placed ads in the Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt to announce several guest performances, the final ones in June 1919 at Marie Pertl’s coffeehouse in the Prater amusement park. On June 17th, the very last performance at the Pertl coffeehouse contained two operettas, Robert Stolz’s Familie Rosenstein, and Alexander Trebitsch’s Der Kerzenfabrikant. On June 18th, the Cabaret “Hölle” initiated the summer season at the Pertl coffeehouse. There is no surviving evidence to suggest that Vienna’s most famous Jewish cabaret, the Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft, ever performed again (Wacks 1999: 123-41).

Jewish cabaret survives at the beginning of the twenty-first century, sometimes openly so, as in the work of Gerhard Bronner (e.g., “Love Song to a Proletarian Girl”), sometimes in the revived cabaret scenes of European urban centers, but more commonly in other forms of the musical stage, be they vaudeville, Tin Pan Alley, or the modern genres of the musical whose genealogy began with Yiddish theater and the Jewish cabaret, and whose repertories of popular song would be unimaginable without the repertories that coalesced on the stage of the Jewish cabaret around the turn of the last century. After World War II, cabaret enjoyed, first, recovery and, then, an upsurge that led to revival by the 1970s. Cabaret can claim audiences and new traditions throughout Europe, with specializations ranging from comedy to political satire. Cabaret was able to survive transitions to radio and television, and new musical styles have come to share the stage with the more traditional genres and repertories of cabaret.

After the Holocaust—after the eruption of the volcano, that is—the Jewishness of cabaret, however, slid precariously close to a different periphery. The several stars of Jewish cabaret who survived in exile—for example, Fritz Spielmann, Georg Kreisler, and Friedrich Holländer—turned their talents toward other media and different stages. Whenever possible, they chose to develop their trade in Hollywood, and several were greeted by notable success in the American film industry. At the turn of our own century, nonetheless, we are fortunate to be able to greet a minor revival, though really more a sort of final reprise. Historical recordings have been remastered for CD (see the “Selected Discography” below), and the older stars, most now retired from Hollywood, have more or less open invitations to revisit the cabaret stages they left in their youths. We begin to realize, if only tentatively, that the Jewish cabaret tradition of Central Europe, against all odds, retains its integrity even after the eruption of the volcano. Its complex web of dialects, its subtle jokes and knee-slapping skits, and its surfeit of cloying love songs notwithstanding, the core of the tradition itself remains somehow intact, inviting us to revisit the many sites that were very real milestones along the journey traveled by composers, musicians, and actors of Jewish cabaret. If we listen, the final refrain of Gustav Pick’s “Viennese Coachman’s Song” still resonates.

Mein Stolz is i bin halt an aechts Weanakind,

A Fiaker, wie man net alle Tag findt,

Mein Bluat is so lüftig und leicht wie der Wind

I bin halt an aecht Weanerkind.

He was proud to be a true child of Vienna.

He served as a coachman, the top of the line.

His blood coursed and ran as swiftly as the wind.

He was truly a child of Vienna.

Selected Bibliography

Akademie der Künste, ed. 1992. Geschlossene Vorstellung: Der Jüdische Kulturbund in Deutschland, 1933-1941. Berlin: Edition Hentrich.

Aschheim, Stephen E. 1982. Brothers and Strangers: The East European Jew in German and German Jewish Consciousness, 1800-1923. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Beckermann, Ruth, ed. 1984. Die Mazzesinsel: Juden in der Wiener Leopoldstadt 1918-1938. Vienna: Löcker Verlag.

Bohlman, Philip V. 1989a. “The Land Where Two Streams Flow”: Music in the German-Jewish Community of Israel. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Bohlman, Philip V. 1989b. “Die Verstädterung der jüdischen Volksmusik in Mitteleuropa, 1890-1939.” Jahrbuch für Volksmusikforschung 34: 25-40.

Bohlman, Philip V. 1994. “Auf der Bima/auf der Bühne – Zur Emanzipation der jüdischen Popularmusik um die Jahrhundertwende in Wien.” In E. T. Hilscher and T. Antonicek, eds., Vergleichend-systematische Musikwissenschaft, pp. 417-49. Tutzing: Hans Schneider.

Bohlman, Philip V., and Otto Holzapfel. 2001. The Folk Songs of Ashkenaz. Middleton, Wisc.: A-R Editions. (Recent Researches in the Oral Traditions of Music, 6)

Brenner, David A. 1998. Marketing Identities: The Invention of Jewish Ethnicity in Ost und West. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Brusatti, Otto. 1998. Verklärte Nacht: Einübung in Jahrhundertwenden. St. Pölten: NP Buchverlag.

Budzinski, Klaus. 1961. Die Muse mit der scharfen Zunge: Vom Cabaret zum Kabarett. Munich: Paul List Verlag.

Budzinski, Klaus. 1985. Das Kabarett: 100 Jahre literarische Zeitkritik – gesprochen – gesungen – gespielt. Düsseldorf: ECON Taschenbuch Verlag.

Czáky, Moritz. 1996. Ideologie der Operette und Wiener Moderne: Ein kulturhistorischer Essay zur österreichischen Identität. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag.

Dalinger, Brigitte. 1998. “Verloschene Sterne”: Geschichte des jüdischen Theaters iin Wien. Vienna: Picus Verlag.

Dalman, Gustaf Hermann. 1891. Jüdischdeutsche Volkslieder aus Galizien und Russland. 2nd ed. Berlin: Evangelische Vereins-Buchhandlung.

Eliasberg, Alexander. 1918. Ostjüdische Volkslieder. Munich: Georg Müller.

Ewers, Hanns Heinz. 1904. Das Cabaret. Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler.

Fechner, Eberhard. 1988. Die Comedian Harmonists: Sechs Lebensläufe. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne Verlag.

Henneberg, Fritz. 1984. Brecht Liederbuch. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Holländer, Friedrich. n.d. Von Kopf bis Fuß . . . Berlin and Munich: Ufaton-Verlag. (Collection of well-known Holländer songs, arranged for piano and voice)

Jelavich, Peter. 1993. Berlin Cabaret. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Keil, Martha, ed. 1995. Jüdisches Stadtbild: Wien. Frankfurt am Main: Jüdischer Verlag.

Kift, Roy. 1998. “Reality and Illusion in the Theresienstadt Cabaret.” In Claude Schumacher, ed., Staging the Holocaust: The Shoah in Drama and Performance, pp. 147-69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kraus, Karl. 1992. Theater der Dichtung: Nestroy – Zeitstrophen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag. (Karl Kraus Schriften, 14).

Der letzte Schmetterling: Kabarett und Lieder aus Theresienstadt. 1992. Ruth Frenk, mezzo-soprano; Karin Strehlow, piano. Erasmus producties WVH 037 (audio recording).

Migdal, Ulrike. 1986. Und die Musik spielt dazu: Chansons und Satiren aus dem KZ Theresienstadt. Munich: Piper Verlag.

Mittler-Battipaglia, Diana. 1993. Franz Mittler: Austro-American Composer, Musician, and Humorous Poet. New York: Peter Lang. (Austrian Culture, 8)

Nathan, Hans, ed. 1994. Israeli Folk Music: Songs of the Early Pioneers. Madison, Wisc.: A-R Editions. (Research Researches in the Oral Traditions of Music, 4)

Pressler, Gertraud. 1995. “… ‘an echt’s Weanakind’? Zur Gustav Pick-Gedenkfeier am Wiener Zentralfriedhof.” Bockkeller: Die Zeitung des Wiener Volksliedwerks 1 (1): 6-7.

Ringer, Alexander L. 1990. Arnold Schoenberg: The Composer as Jew. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Rösler, Walter, ed. 1991. Gehn ma halt a bisserl unter: Kabarett in Wien von den Anfängen bis heute. Berlin: Henschel Verlag.

Salmen, Walter. 1991. “. . . denn die Fiedel macht das Fest”: Jüdische Musikanten und Tänzer vom 13. bis 20. Jahrhundert. Innsbruck: Edition Helbling.

Scheu, Friedrich. 1977. Humor als Waffe: Politisches Kabarett in der Ersten Republik. Vienna: Europaverlag.

Segel, Harold B. 1987. Turn-of-the-Century Cabaret: Paris, Barcelona, Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Cracow, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Zurich. New York: Columbia University Press.

Shahar, Natan. 1993. “The Eretz Israeli Song and the Jewish National Fund.” In E. Mendelsohn, ed., Modern Jews and Their Musical Agendas, 78-91. New York: Oxford University Press.

Teller, Oscar. 1985. Davids Witz-Schleuder – Jüdisch-Politisches Cabaret: 50 Jahre Kleinkunstbühnen in Wien. 2d ed. Darmstadt: Verlag Darmstädter Blätter.

Veigl, Hans. 1986. Lachen im Keller: Von den Budapestern zum Wiener Werkel: Kabarett und Kleinkunst in Wien. Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau.

Veigl, Hans, ed. 1992. Luftmenschen spielen Theater: Jüdisches Kabarett in Wien, 1890-1938. Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau.

Wacks, Georg. 1999. “Die Budapester Orpheum Gesellschaft – eine Institutionsgeschichte.” Master’s thesis, Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien.

Album Details

PROGRAM

CD 1 (77:23) All songs sung in original language

CD 2 (77:40) All songs sung in English

Recorded: March 13-16, 2002 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: Elizabeth Ostrow

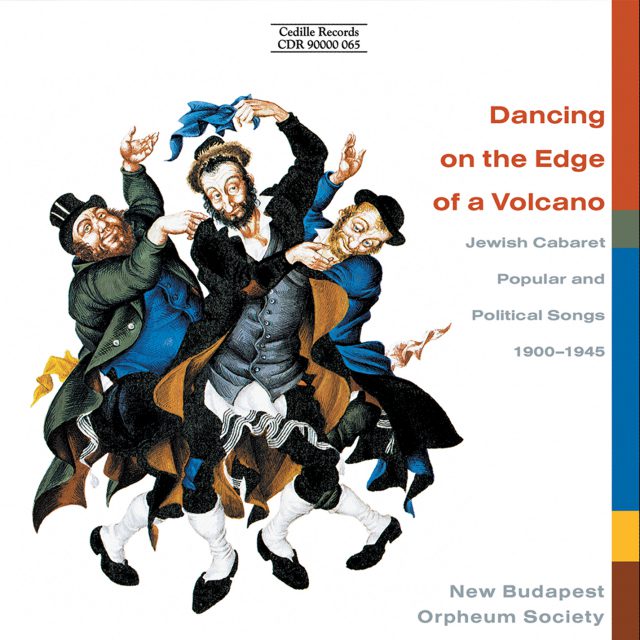

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Front Cover Illustration: “Dancing” illuminated by Arthur Szyk, Lodz, Poland, 1936. Reproduced with permission of Alexandra Szyk Bracie and Irvin Ungar/Historicana. Notecards with this image may be obtained through Historicana (650.343.9578 or www.szyk.com)

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Philip V. Bohlman

© 2002 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 065