Store

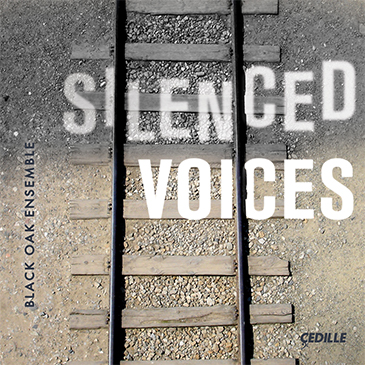

Black Oak Ensemble, a string trio boasting three of Chicago’s most enterprising and dynamic chamber musicians, makes its recording debut with Silenced Voices, an album of intriguing works by six promising, early 20th century Jewish composers originally from Austria-Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the Netherlands. One survived World War II as a member of the Dutch resistance, the others perished in concentration camps and elsewhere in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Silenced Voices includes the world premiere recording of wartime survivor Géza Frid’s early Trio à cordes, Op. 1, an inventive work infused with Hungarian folk music influences. Composer-cellist Paul Hermann’s Strijktrio, a forward-looking, cosmopolitan work from the early 1920s, shares its melodies among all three instruments. Dick Kattenburg’s youthful Trio à cordes was praised in a 1938 concert review for its “remarkable mastery and a very personal style.” Gideon Klein’s Trio for violin, viola and cello is notable for its treatment of a Moravian folk song that serves as the theme of its middle movement. Hans Krása’s Tánec (“Dance”) is a five-minute whirl of dancelike episodes framed by the sonic evocation of trains. His Passagalia is more somber, with its own train motifs, while its companion Fuga bears shades of Germanic and Czech influences and occasional grotesque touches. Sándor Kuti’s Serenade for String Trio brims with Hungarian folk music and piquant chord clusters. His Franz Liszt Academy classmate, conductor Sir Georg Solti, later proclaimed that Kuti “would have become one of Hungary’s greatest composers.”

This album is made possible by support from Eva Lichtenberg and Arnold Tobin

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with the Black Oak Ensemble on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

DICK KATTENBURG (1919–1944)

SÁNDOR KUTI (1908-1945)

Serenade for String Trio

HANS KRÁSA (1899–1944)

Passacaglia & Fuga for String Trio

HANS KRÁSA (1899–1944)

Tánec for String Trio

GIDEON KLEIN (1919–1945)

Trio for violin, viola, and cello

PAUL HERMANN (b. 1902–1944)

GÉZA FRID (1904–1989)

Trio à cordes, Op. 1

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletSilenced Voices

Notes by Robert Elias

What do we hear when we listen to works that have a fraught history? Do we hear only the music or, given the compelling and tragic back stories of each of the composers featured here, do we hear more than that?

Whenever we attend a concert or listen to a recording, we hear the music through the aural prisms of our own musical experiences and our personal histories. Is music enhanced, diminished, or something else entirely when we first hear works that were written by composers murdered by the Nazi regime (as was the case for all but one of the pieces on this recording)?

The composers featured on this recording would likely prefer that the listener find their pieces interesting, appealing, perhaps moving, not because of the circumstances of their deaths, but because the music itself evokes these feelings through their compositional mastery. Yet we cannot fail to recognize and take into account that were it not for the crimes perpetrated against them, the music of these composers would surely be more plentiful and better known than it is today.

These larger questions notwithstanding, what is certain is that the works on this recording receive committed, brilliant performances by Black Oak Ensemble, and such performances are a gift to any composer. These works “spoke” to these musicians in ways that compelled them to devote many hours to their study, rehearsal, repeated performances, and this recording.

Perhaps that is all we really need to know.

DICK KATTENBURG (1919–1944)

Trio à cordes

Written when the composer had just turned 19-years-old (and perhaps experiencing the flush of first love), Dick Kattenburg’s String Trio is a five-minute burst of youthful exuberance. It appears to have been composed as an independent piece and not necessarily part of larger multi-movement work. According to musicologist Carine Alders:

A local newspaper published a review in December of 1938 of a concert at Hugo Godron’s home. With violinist Dick Kattenburg and Theo Kroeze on viola, they played Mozart’s flute concerto in a chamber music arrangement. At this concert, a string trio by one of “Godron’s advanced composition students,” Dick Kattenburg, had been performed for the first time and according to the critic it was: “A fairly compact piece showing remarkable mastery and a very personal style; looking forward with great interest to his further development.”…A remarkable ink and watercolor drawing adorns the cover page, dated 1938, depicting the three musicians: right Dick Kattenburg, center Theo Kroeze and left cellist Anton Dresden, who later became conductor of Toonkunst Bussum Choir and Orchestra… The score of the string trio is signed with the pseudonym “Van Assendelft Van Wijk,” and on the back cover, between some small sketches, is a portrait of Hitler and sketch of a soldier giving a Hitler salute. To what extent were these young musicians aware of the dark times ahead?

Kattenburg managed to survive most of the war and the German occupation of the Netherlands by changing his location often. In the spring of 1944, however, his luck ran out — possibly as a result of an informant — and he was sent to the Dutch concentration camp at Westerbork, which served as a Dutch way station to Auschwitz, where Kattenburg is presumed to have perished. [1]

SÁNDOR KUTI (1908–1945)

Serenade for String Trio

Like the artistic milieus of most major cities that fell under Nazi control from the late 1930s through 1945, the musical community of Budapest was devastated by the persecution and murder of the Jewish creative class. The crop of composers that had recently emerged from the famed Franz Liszt Academy was particularly hard-hit, including the very promising Sándor Kuti. Sir Georg Solti, one of Kuti’s Academy classmates, later called him “exceptionally gifted” and wrote: “I used to visit him at his family’s desperately poor little catacomb of a home. I am convinced that, had he lived, he would have become one of Hungary’s greatest composers.” [2]

Kuti died in 1945 (or possibly late-1944) while held in a forced labor camp in Ukrainian territory. He continued to compose during his imprisonment (using scraps of paper that he painstakingly lined with musical staves) and, with the help of a sympathetic guard, even managed to send to his pregnant wife (who remained hidden in Budapest) his final work, a Sonata for Solo Violin.

Kuti wrote his Serenade for String Trio in 1934, when he was in his mid-20s. In the first movement, as with the works by Géza Frid and Pál Hermann, the spirit of Hungarian folk music can be clearly discerned, with piquant chord clusters reminding the listener that this is a work of the academy, not the provinces. The machine-like drive of the second movement, marked Giocoso, may suggest the sounds of some of Kuti’s Russian contemporaries such as Shostakovich or Prokofiev — although it is impossible to know if Kuti had encountered their music or whether these aural “memes” were simply floating in the air of Eastern Europe. The third and final movement, marked Adagio ma non troppo, is a stark contrast to the preceding movements: an unresolved lament, evoking memories of his teachers Laszlo Weiner and, perhaps most strikingly, Béla Bartók.

HANS KRÁSA (1899–1944)

Passacaglia & Fuga

Tánec

Hans Krása was firmly 20 years older than Gideon Klein and had established himself as a substantial composer when he too was interned in Theresienstadt for approximately the same two-year period prior to October 1944, sent to the infamous ghetto-concentration camp within the fortress walls of the Czech garrison town of Terezín. Called Theresienstadt during the German occupation, this place was both dreadful and remarkable: sitting on the edge of the certain death that awaited the vast majority of its internees while, at the same time, existing as an artistic and intellectual bastion of creativity that was unlike any place, large or small, under Nazi control during the war. After two years there, Krása when he was sent to Auschwitz in October 1944 and murdered two days after his arrival.

Krása is best known for his children’s opera Brundibár, which, written before his internment, was performed more than 50 times in Theresienstadt. This little allegorical opera deserves its many revivals and productions, although it is a bit unfair to Krása’s musical legacy that, for many people, Brundibár is their only experience of his work. (It is as if the only Prokofiev composition we ever heard was Peter and the Wolf.) The Krása works featured here — Tánec and the Passacaglia and Fugue — were written in Theresienstadt during the final year of his life and provide a fuller view of a composer who wrote vocal works, orchestral works, cantatas, chamber music, and a major opera that premiered in Prague in 1933 with the young George Szell conducting.

The Passacaglia is a somber exercise, with episodes of florid interactions and ominous-sounding train motifs. The Fugue takes flight immediately with the appearance of the theme in the viola and charges onward, with shades of Germanic and Czech influences and the occasional grotesque touches that gave Krasa’s music an extra sonic bite. Although titled Tánec (“Dance”), this five-minute romp suggests not a traditional dance, but rather an almost parodic whirl of dancelike episodes, framed by an aural depiction of trains in motion — approaching and receding, perhaps even stopping for water in a provincial village as the townspeople sleep.

GIDEON KLEIN (1919–1945)

Trio for violin, viola and cello

20 years younger than Krása, Gideon Klein was a promising pianist and composer when, in December 1941, he was interned in Theresienstadt for much of the same period as Krása. sent to the infamous ghetto-concentration camp within the fortress walls of the Czech garrison town of Terezín. Called Theresienstadt during the German occupation, this place was both dreadful and remarkable: sitting on the edge of the certain death that awaited the vast majority of its internees while, at the same time, existing as an artistic and intellectual bastion of creativity that was unlike any place, large or small, under Nazi control during the war.

The two outer movements of Klein’s Trio for Strings, jaunty and propulsive, frame a deeply moving Theme and Variations middle movement. So dominant is the middle movement of the work — its length is greater than the first and third movements combined — that much has been written about its musical and philosophical significance. The work appears to have been completed shortly before Klein and most of the other artists and intellectuals held in Terezín were transported to Auschwitz in October 1944. Klein was sent on to a camp at Fürstengrube, where he perished just days before the camp’s liberation in 1945.

Musicologist Michael Beckerman has written much about Klein’s String Trio, the significance of the Moravian folksong that serves as the theme of the middle movement, hidden references, and even hidden messages. More importantly, Professor Beckerman cautions against reading too much into too little information. In a probing essay for the website of The OREL Foundation, Beckerman cautions against “giving preference to the stories we would most like to tell.” [3]

PAUL HERMANN (b. 1902–1944)

Strijktrio

Pál Hermann (aka Paul Hermann), also a product of Budapest’s Franz Liszt Academy, drew less directly from folk music sources, leaning instead toward a more cosmopolitan style that exhibited signs of what Bartók celebrated as freedom from the “tyrannical rule of the major and minor keys.”

In this work from the 1920s, Hermann demonstrates a particular mastery of stringed instruments and, while he was a cello virtuoso of the first rank, in this Trio he is careful to share the melodic wealth with the violin and viola, each instrument performing in the foreground as well as in accompaniment throughout this one-movement gem. The structure is episodic, a mix of rondo and variation form, in which two main melodies, modal in character, are passed among the players.

Hermann too sought refuge from Hungary’s Fascist policies in the Netherlands. When the Nazis arrived in that country, he fled to France, where he managed to hide near Toulouse, before being swept up in an April 1944 raid. He was sent to the infamous Drancy concentration camp outside Paris, and then sent eastward toward Lithuania, never to be heard from again.

Thanks to the composer’s grandson, Paul van Gastel, all of Hermann’s extant works can be found on the website of the IMSLP (International Music Score Library Project). Through sampling other Hermann works, the composer’s distinctive compositional voice is easily discerned.

GÉZA FRID (1904–1989)

Trio à cordes, Op. 1

Géza Frid was born and spent his early years in Máramarossziget, which lies in within the historic border region of Hungary and Romania. It is an area rich in folk music traditions, and its melodies were among the earliest catalogued by Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály in their ethnographic research and recording efforts in the early years of the 20th century. Frid spent his formative musical years at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest, where he also came to know, and eventually concertized with, Pál Hermann (whose work is also on this recording). Frid left Hungary and its proto-Fascist anti-Semitic policies in the late 1920s, settling in the Netherlands, where he managed to avoid detection as a “stateless Jew,” and eventually became a citizen and celebrated composer.

Considering the pedagogical influence of Bartók and Kodály, it is not surprising that Frid’s early String Trio exhibits Hungarian folk music influences. The first movement is underpinned by the rhythmic qualities of the Hungarian hurdy-gurdy (tekerő) and bagpipe (duda). In these instruments a drone pitch tends to dominate the harmonic landscape, and this infuses the work with the spirit of regional folk melodies. In the middle movement, a cantabile in 9/8 sets the mood, although the pull of Hungarian duple meter returns in a surprising agitato episode that intrudes on the peaceful scene. The third movement, marked Allegro giocoso all’ ungherese, draws us once again into the provincial musical scene of eastern Hungary in ways both varied and surprising in their invention.

Robert Elias

The OREL Foundation

A music historian by training and an arts executive in practice, Robert Elias has served as the President of The OREL Foundation since its founding by conductor James Conlon in 2007. The foundation is an invaluable online resource for information on the music of composers who were suppressed during the years of the Nazi regime in Europe.

[1] https://www.forbiddenmusicregained.org/search/composer/id/100003

[2]http://orelfoundation.org/journal/journalArticle/remembering_seven_murdered_hungarian_jewish_composers

[3]http://orelfoundation.org/journal/journalArticle/what_kind_of_historical_document_is_a_musical_score

Album Details

PRODUCER James Ginsburg

ENGINEER Bill Maylone

EDITING Jeanne Velonis

GRAPHIC DESIGN Bark Design

RECORDED July 30–31 and September 18–19, 2018, Mary B. Galvin Recital Hall at Northwestern University

PUBLISHERS

Kattenburg: Trio à cordes © 2018 Stichting Donemus Beheer

Kuti: Serenade for String Trio © 1966 Universal Music Publishing Editio Musica Budapest

Krása: Passacaglia & Fuga for String Trio © 2004 Boosey & Hawkes

Klein: Trio for violin, viola, and cello © 1944 Boosey & Hawkes

Hermann: Strijktrio © 1921 Stichting Donemus Beheer

Frid: Trio à cordes, Op. 1 © 1926 Music Center of the Netherlands

© 2019 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 189