Store

Store

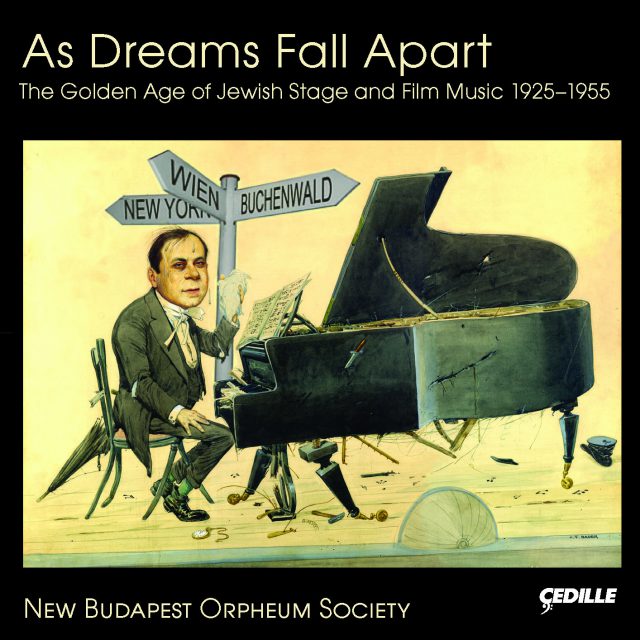

As Dreams Fall Apart: The Golden Age of Jewish Stage and Film Music (1925–1955)

Ilya Levinson, Julia Bentley, Stewart Figa

The New Budapest Orpheum Society, ensemble-in-residence in the Division of Humanities at the University of Chicago, has been tracing the origins, development, and influence of European Jewish cabaret music through extensive historical research and compelling performances in concert and on a series of widely acclaimed albums on Cedille Records.

The ensemble’s third and newest project for Cedille focuses on Jewish stage and film music from the early to mid-20th century, ranging from a turn of the 20th century Viennese broadside to songs from the 1948, Billy Wilder-directed film A Foreign Affair.

Preview Excerpts

On the Shores of Utopia

ELLSTEIN

PERLMUTTER

KÁLMÁN

Dreams from Yesterday & Tomorrow

KORNGOLD

ABRAHAM

LEOPOLDI

Dreamworlds

STRAUSS

Between Traum and Trauma

ULLMANN

Artists

1: (Viennese broadside ca.1900) Instrumental, arr. Levinson

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAs Dreams Fall Apart: Historical Counterpoints of Traum and Trauma

Notes by Philip V. Bohlman

Lay, thus, the foliage together with the souls.

Swing lightly the hammer, let the face bear witness.

Create a crown with the blows absent in the heart,

For the knight who jousts with distant windmills.

They are only clouds that he tolerates not.

Still, his heart clatters with the footfalls of angels.

I quietly gather about me what he does not strike down:

The boundary of red, the center of black.

Paul Celan — “Traumbesitz” / “Grasping Dreams”

The history of sound film begins on a musical stage indebted to the long history of Jewish cabaret. In history’s very first synchronized sound film, Alan Crosland’s 1927 The Jazz Singer, the title character, Jakie Rabinowitz takes to the stage as Jack Robin, enacting and envoicing the struggle between Jewish tradition in Samson Raphaelson’s original play, The Day of Atonement, and the dreams of stardom awaiting him in the jazz clubs and vaudeville stages of New York City. The (real life) jazz singer’s musical transition from stage to film formed at the confluence of real-life transitions for European Jews at the beginning of the twentieth century — migration from rural shtetl to urban ghetto, immigration from the Old World to the New — and of allegorical transitions — from religious orthodoxy to modern secularism, from diaspora to cosmopolitanism. As the old order of European empire collapsed in the wake of World War I, the Jewish musical traditions that had metaphorically represented its political and ideological boundaries (heard in the repertoire recorded on the The New Budapest Orpheum Society’s Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano) gathered new metaphors: those of modernity and modernism, ripe for the tales that would move from the skits of the cabaret stage to the scenes filling the frames of sound film.

Together, these metaphors, tales, and scenes became the stuff of dreams that proliferated in the films of the next thirty years. These were the dreams that fired the imagination of surrealists, launching their own experimental art forms in the mid-1920s and asserting a course for European arts and letters untethered from reality and redeployed on the repeatability of form in new media, above all film. These are the dreams that would fill the arts of the Shoah, the verses of one of its greatest poets, Paul Celan (1920–1970), whose “Grasping Dreams” epigrammatically opens the brief history for whose close it also stands a sentinel. These dreams offered hope and documented its destruction; they shaped the images of utopian worlds, yet accompanied their disintegration into dystopia; they embodied the fruits of lives well lived, yet clung to the shreds of those torn apart. Dislodged by the tragedy of history from 1925 to 1955, these are the dreams we capture musically on this double-CD, allowing us to hear them once again even as they were falling apart.

Jewish music provided far more than just the dialect for the jazz singer’s voice in early sound film. In 1924–25, Hanns Eisler (1898–1962) — whose songs from the Hollywood Songbook appear on each of the New Budapest Orpheum Society’s albums, including the “Five Elegies” and “L’automne californien” on this one (disc 2, track 8–12) — collaborated with filmmaker Walter Ruttmann to compose a passacaglia for the experimental film, Opus III, synchronizing shifting abstract shapes with the modernist musical vocabulary Eisler had developed in his years of study with Arnold Schoenberg. Eisler’s Opus III symbolizes the moment of beginning for the history of stage and film music that frames this recording.

Eisler’s work was followed five years later in Berlin by Josef von Sternberg’s 1930 Der blaue Engel (The Blue Angel), the first German-language synchronized sound film. “The Blue Angel” of the film’s title (the film was based on Heinrich Mann’s 1905 novel, Professor Unrat) was a cabaret in a German harbor city, and the most of the music was filmed diegetically (i.e., performed on screen, not recorded separately) on or around the stage in the Blue Angel cabaret, performed by Friedrich Holländer’s jazz band, Weintraub’s Syncopators, and Marlene Dietrich. Another ontological moment for film music, and Jewish cabaret, was there. It would be there once again — and composed once again by Friedrich Holländer (1896–1976) for diegetic performances by Marlene Dietrich in the Lorelei cabaret in Billy Wilder’s 1948 A Foreign Affair, the three songs from which close this album (disc 2, tracks 16–18). The historical arc from the stage of the Blue Angel to that of the Lorelei, from the eve of Nazism to the wake of the Holocaust, once again realizes a narrative of film music from which Jewish cabaret is inseparable.

Film music and its early history contain fundamental narratives for the historical transition and tragedy faced by Jews from the mid-1920s to the decade after the Holocaust. Film provides a medium that moves between what the viewer and listener perceive as real and the fictional representation of life. It is for this reason, too, that it attracted the attention of Hanns Eisler and Theodor W. Adorno (1903–1969), who together wrote the first large-scale monograph on composing for moving picture synchronization, Composing for the Films (Oxford University Press, 1947), the product of their collaboration in American exile for the Rockefeller Foundation’s “Film Music Project.” The book results from the intertextuality of counterpoint on many levels, provided by Eisler, already famous for the music in films such as Kuhle Wampe (1931–1932, to a script by Bertolt Brecht), Hangmen Also Die (1943, directed by Fritz Lang), None but the Lonely Heart (1944, directed by Clifford Odets), and The Circus (1947, directed by Charlie Chaplin). Adorno, who tried his hand at composition but was known primarily as a philosopher at the Frankfurt School of Social Research, before and after World War II, provided the sociological and philosophical counterpoint in the book.

Forming what they called “dramaturgical counterpoint,” Adorno and Eisler regarded film music as moving — mediating as a technological and aesthetic medium — between the real and the imaginary. Film music intensifies this capacity to mediate between the diegetic and the non-diegetic (music the viewer sees on the screen and music performed and recorded elsewhere), thereby paving the way between reality and dream. Here, we witness the critical issues about representing reality and dreams: film and music combine to constitute the aesthetic foundations of both. Many consider film the most highly representational of the modern arts. Viewers want to believe they are witnessing real people in real-life situations on the screen. In The Jazz Singer the great immigrant Jewish cantor, Yosele Rosenblatt (1882–1933), both was and was not himself as he sang Yiddish and Hebrew songs on the stage of Chicago’s Auditorium Theatre in the film. Music, by contrast, is often considered the least representational of the arts. The relation between film and music, it follows, is one of contrast and dissonance, and this is critical for the ways film transforms reality into dreams.

Film and music interact in particularly intricate ways through processes I call “cabaretesque.” The worlds represented by the cabaretesque on stage and in film are turned inside-out. Self becomes other, other becomes self. The world on the stage is made to appear as if it were everyday, albeit with reflections and shadows that change the ways we perceive it. Musicians perform diegetically in film as in an intimate space, where the self and other explore their intimacy through the interplay of darkness and light — that which is hidden and that which is revealed. Revelation and reflection become one, as the cabaretesque becomes the mirror through which spectator and listener enter the moment in which we see ourselves as others.

Historically, the cabaretesque emerged at a moment when cultural theory and the techniques of cultural production explored the transformation of meaning through reflections from mirrors. The mirror was as important for the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud as it was for that of noted French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Mirrors enter the gaze of cubists and surrealists — Pablo Picasso and René Magritte are obvious examples — and of impressionist and the twelve-tone composers. And mirrors become the lens of the alter-ego in the films that captured cabaret and embedded it in Jewish film history. The mirror in film noir becomes the oracle for the film song of the great cabaret composers, Hanns Eisler and Friedrich Holländer, as well as the other composers and lyricists whose songs fill this recording.

The metaphorical mirror in the cabaretesque also shapes the ways in which nothing is really as it seems. The cabaretesque engenders dreams, and it creates the illusions that allow the listener to believe it is possible to enter alternative worlds. Is Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin, the Al Jolson title role in The Jazz Singer, white or black, Jew or non-Jew, star of the New York stage or son of the immigrant cantor? He is, of course, all of these because, in cabaretesque style, he performs all these roles. What would cabaret be if it did not possess the power to distort, distract, and divert our gaze from the harsh realities of the world beyond the footlights? What would it be if it did not unleash dreams in a golden age during the most tragic period of modern Jewish history?

Allegory, Alienation, and Exile: Song and the Yiddish Film Musical

Sound entered film at one of the most auspicious and spectacular moments in the history of Yiddish theater. From its earliest years in the 19th century, Yiddish theater troupes had been mobile and cosmopolitan, moving from across the shtetl culture of Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe to the metropoles of Central Europe as they absorbed growing numbers of Jewish immigrants entering the public sphere of the 19th century. In Vienna, Berlin, and other cities with growing Jewish populations, Yiddish theater provided a musical and narrative mirror for new forms of Jewish stage music. Jews arriving from the shtetl shed the traditional cloaks of tradition and engaged — sometimes haplessly, often successfully — with the challenges of modernity (e.g., “Die koschere Mischpoche,” disc 1, track 1). Both allegory from the biblical past and alienation from present modernity heightened the fragility of the characters on the Yiddish stage. The cabaretesque in Yiddish musicals restaged that fragility, rerouting immigration to exile, from the familiarity of the past to exile into the future.

The future for Yiddish theater and the Yiddish musical was the New World, especially the great metropoles of the United States and Argentina. Already by the beginning of the 20th century, Yiddish stage music was attracting audiences in New York City and Chicago. By the 1920s, an active Yiddish theater scene had established roots and spread into most areas of American popular music, from vaudeville to jazz to cinema. It was this theater scene that The Jazz Singer captured in 1927, weaving together the larger themes of allegory, alienation, and exile from the many streams of American popular music. Yiddish theater paved the way for new film composers and stars, such as Boris Thomashevsky (1890–1957), Abraham Ellstein (1907–1963), and Molly Picon (1898–1992) (disc 2, track 7; disc 1, track 2; and disc 2, track 15). Because these themes from American Jewish music continued to reflect the traditions of Yiddish stage music, it is hardly surprising that they could quickly be transformed by Yiddish cinema and its golden era of the 1930s, which would prove to be perhaps the most spectacular — and short-lived — of all traditions of Jewish film music.

Yiddish film musicals were the product of musicians and music on the move, a process of triangulation that witnessed the journeys of actors and directors from the United States, and musicians from Vienna and Berlin, all of whom would gather in Poland for the filming and production of films in the Yiddish studios of Warsaw and elsewhere in Poland and Lithuania. One of the best-known of all Yiddish film directors, Joseph Green (1900–1996), illustrates this tripartite cosmopolitanism quite strikingly. Born in Łódź, Poland, Green immigrated to New York in 1924, where he immediately received roles on the Yiddish stage and soon thereafter in film (e.g., a brief appearance in The Jazz Singer). By the 1930s, Green had become increasingly involved with Yiddish film, and by the late 1930s he was one of its most important directors. In the late 1930s, he directed several of the most famous of Yiddish film musicals in Warsaw, including Yidl mitn fidl (Yidl with a Fiddle) and A brivele der mamen (A Letter from Mother). The latter employs the themes of alienation and exile in the song of the same name on this recording (disc 2, track 6).

The characters in Green’s films sing of and in their dreams that seek a better future, beyond the poverty of traditional diaspora and exile. In the 1937 Der purimshpilr, for example, exile and displacement are rendered as normative, growing from the musical contrafacts of biblical texts, and the myths that emerged from them. The Jewishness of the production is undeniable but, critically, the symbols and narratives multiplied so that they juxtapose tradition and modernity. They form narrative counterpoint as plays within plays, obscuring the very boundaries between reality and the dream sequences performed through song. The distinction between fact and fiction, reality and dreaming, is traditional and historically situated in the medieval and ancient Jewish past. The title character plays the double role of Ahasver, both the “wandering Jew” and a real character within the Purim story in the biblical book of Esther. In Der Purimshpilr he once again seeks a place of rest, realized through the love of the Esther in the movie, the beautiful daughter in a traditional shtetl family. As the film draws to a close, music portrays the continuing allegory of alienation and exile. Accompanied by the Purim actor and her new lover, Esther sings the song, “Mein Shtetl,” on one stage after another, in a mise en scène that unfolds as a Yiddish folk song becomes an art song and then a popular tango before culminating in a full-fledged jazz dance, realizing the dream of a brighter future on the stages of the world, hauntingly only two years before Germany invaded Poland, closing the curtains on Yiddish film musicals forever.

The Journey from Stage to Film

Jewish music found its way from stage to film in many different ways, some direct, others circuitous. Early film musicals often kept the stage clearly in view of the camera, giving the viewing public the sense that they were witnessing a live musical performance, not merely its representation in a cinema. We see the front of the proscenium and backstage, and the characters enter the stage as if passing from the real world to a dreamworld. Musical films often took musical performance on the stage as their subject matter, becoming musicals about musicals, connecting stage to film through the cabaretesque in music. The 1936 filming of Showboat is one of several notable examples of the history of film musicals about musicals. (The 1929 filming of Edna Ferber’s novel, Showboat, was itself one of the first-ever talkies.) In 1937, Der Purimshpilr follows its title character through layer upon layer of stage performances, from the medieval Purim play in the Polish shtetl to the popular-music stage in the metropole.

The musical journey between stage and film also unfolded as detours through the rise of fascism, World War II, and the Shoah, resulting in both the survival and revival of Jewish music thereafter, often unexpected and paradoxical, as in the case of the two most popular Heimatfilme (homeland films) of Germany and Austria, Schwarzwaldmädel (Black Forest Girl) and Im weißen Rößl (The White Stallion Inn). No composer of operetta and popular song was more intimately connected with the nostalgia of Heimatfilm — the vastly popular postwar genre, that took traditional life in the German countryside as its subject — than Léon Jessel (1871–1942). In 1917, still during World War I, Jessel composed Schwarzwaldmädel, which quickly became an enormous stage success. A decade and a half later, it became even more beloved as a sound film that captured the essence of Germanness. Its Jewish composer notwithstanding, Schwarzwaldemädel was frequently performed during the era of National Socialism and throughout World War II, thereafter enjoying the honor of becoming one of the first films to be remade in the postwar era. The fate of the Schwarzwaldmädel’s composer, Léon Jessel, could not have contrasted more with that of his most famous work for stage and film. Believing that there were still possibilities for cooperation and compromise with Nazi cultural organizations, Jessel remained in Germany. In 1942, he was arrested for “medical reasons” and died in Gestapo custody.

How do we disentangle the life of Léon Jessel from that of his Schwarzwaldmädel, the quintessential Heimatfilm in postwar Germany? Schwarzwaldmädel symbolized Germanness through the aesthetic lens of volkstümliche Musik (folklike music), which nostalgically drew Germans into the timeless space of the past. The works of other Jewish operetta composers (and there were many) suffered quite different fates. For example, Emmerich Kálmán’s 1928 Die Herzogin von Chicago (The Duchess of Chicago), with its representation of ethnic and racial difference on the stage, was banned and led to Kálmán’s exile and demise. And yet, when Kálmán composed his final work in the United States, Arizona Lady, in 1953, the last year of his life, it was a German radio performance that brought it briefly to life. Arizona Lady’s revival came almost sixty years later, first in Chicago (2010) and then in Berlin (2014–15 season). With Julia Bentley’s performance of Kálmán’s “Wir Ladies aus Amerika” (disc 1, track 4) the New Budapest Orpheum Society seeks to rechannel the historical journey of Jewish stage and film music.

The Cover of Emmerich Kálmán’s 1928 Die Herzogin von Chicago (piano-vocal score)

Irony and imperfection become the stuff for cabaret and film music, quickly opening a public space for other Jewish musicians after World War II. The history of cabaret in postwar Germany intersects in many ways with that of film and film music. Both are settings for the represence of Jewish musicians. We witness this most clearly when we see Friedrich Holländer lead the house band, Hotel Eden Syncopators, in A Foreign Affair, just as he did in Der blaue Engel (disc 2, tracks 16–18).

Friedrich Holländer and Marlene Dietrich on the Lorelei Stage in Billy Wilder’s A Foreign Affair (1948)

In postwar Germany and Austria the cabaret of the past became the basis for a new generation of films that used music to re-present the utopia of Heimat. Great cabaret musicians, such as Hermann Leopoldi (1888–1959), barely survived the Holocaust, and it was too late in their careers to return to the stage, but their music, cloyingly searching for another world, became the basis for film. We see this, for example, in Ralph Benatzy’s Im weißen Rößl, the most important Austrian Heimatfilm of the postwar years. Among its cabaret techniques, it uses Jewish potpourri in the opening scenes. No work of opera or operetta has been filmed as many times as Im weißen Rößl. The sound-film version of the revue-operetta, directed by Austrian Carl Lamac, dates from 1935. After World War II, the revue-operetta was transformed into several well-known film versions, all of them reshuffling the pieces of the potpourri and stylistic mix that played with nostalgia in a non-ironic way.

As ironic interwar nostalgia, Im Weißen Rößl (first staged in Berlin, 1930) might be interpreted as a simple and straightforward projection of a lost imperial world, except for its music, which generously adapts cabaret and jazz styles to the operetta stage: waltzes become jazz, Ländlers tangos, Schottisches foxtrots, Dorfkapellen (village bands) on-stage jazz bands, and village residents become the chorus line in a revue. Im Weißen Rößl was, moreover, no traditional operetta, not even of the type Emmerich Kálmán might have composed for the Vienna stage (e.g., Die Herzogin von Chicago, which uses jazz genres throughout). Rather, it was a revue-operetta — a stage work that combined revue, vaudeville, cabaret, and other forms of theater. It was a potpourri, and it consciously drew this tradition from Jewish cabaret and stage music (cf. “Aus der Familie der Sträusse,” disc 1, track 10). The songs came from many sources and had many composers — Ralph Benatzky (1884–1957) (who received primary billing), Robert Stolz (1880–1975), and Karl Farkas (1893–1971), among others. Other songs, from the cabaret works of Friedrich Holländer and Hermann Leopoldi, were sampled and mixed into the revue. As a potpourri for the stage, Im Weißen Rößl’s form and style — cabaret and jazz — signified the Jewish roots of those who contributed musically to it.

Utopian Dream, Dystopian Nightmare

The historical counterpoint unleashed by the cabaretesque during the golden era of Jewish film music could not dislodge dreams of utopian Jewish worlds from the nightmares of the Shoah’s dystopian reality. Ideas and experiments in utopia-building had a long history in European Jewish communities, but their ability to return after World War II and the Holocaust had to respond first to the challenge of a dystopian reality. Film provided one of the most significant sites for resolving the disjuncture of utopia and dystopia. Because the historical counterpoint of the cabaretesque actually forged a space between utopia and dystopia in film and film music, I turn briefly and historically to that space in the wake of the Shoah.

After the pogroms in Russia during the 1880s and the rise of public anti-Semitism in the Habsburg Monarchy during the 1890s, forced and voluntary migrations increasingly mobilized European Jewish communities. Workers’ movements and student movements alike turned to utopian projects. Jewish workers were actively involved as leaders and foot soldiers in the rise of socialism. The socialist and communitarian models of socialism provided templates for the rise of Zionism in its several forms: religious, political, and cultural. With the organization of Zionism on an international level by its founding figure, Theodor Herzl, images of utopia were assuming concrete forms by the turn of the 20th century, for example, in his dramatic work, Das neue Ghetto (The New Ghetto) — the explicit evocation of a modern, industrial city that rose from the ashes of the Jewish ghetto.

Dystopian images of modernity also proliferatd among Jewish intellectuals and in Jewish artistic movements as the Europe of empire gave way to the Europe of modern crisis after World War I. The rapid urbanization of Jewish society, in particular, led to the spread of industrial neighborhoods, unemployment, and poverty. The migration to the city and then beyond through vast immigration waves that tore families apart and displaced traditional culture generated new forms of art and literature. These were mirrored in the Yiddish stage of the turn of the 20th century, and in Yiddish film and film musicals in the 1920s and 1930s (e.g., “Dos pintele Yid,” disc 1, track 3, and “Erlekh zayn,” disc 2, track 7).

Music as a mobilizing force for the imagination of utopia and dystopia was similarly familiar. The Jewish folk-song book, a phenomenon that first emerges in 1883, but proliferates at an enormous pace through World War I and into the rise of fascism, becomes a literal anthology of the possibilities for utopia. Yiddish song, following the Yiddish stage into cabaret and then Yiddish film, also stages utopian worlds as alternatives to lived-in dystopian worlds. Cabaret song and popular music, similarly, conjure up images of the city as a world out of control and overrun by chaos.

The stage and film composers whose songs fill this double-CD forged musical narratives that would suture the counterpoint between the utopian and dystopian worlds unleashed by the dreams of the golden era. Hermann Leopoldi, whose songs from before, during, and after the Shoah introduce very special voices of counterpoint into As Dreams Fall Apart, turned to the images of dreaming to project utopia as a means of forestalling and escaping dystopian destruction. Leopoldi’s Vienna can be a site of nostalgia (“In einem kleinen Café in Hernals,” disc 2, track 4) or of decaying modernity (“Wo der Teufel gute Nacht sagt,” disc 2, track 5). Dreams provide alternatives for the realities of the everyday (“Café Brasil,” disc 2, track 1, and “I bin a stiller Zecher,” disc 2, track 2), but they also frame the cruel realities of history (“Die Novaks aus Prag,” disc 1, track 7). As fantastic as they are (“Composers’ Revolution in Heaven,” disc 1 track 8), Leopoldi composed his dreamworlds knowing full well that, ultimately, we awaken from them.

After the Shoah, film and film music increasingly became the scripts for the counterpoint between utopia and dystopia. It is this counterpoint that stages the mise en scène for Friedrich Holländer and Billy Wilder (1906–2002) in their 1948 film, A Foreign Affair, the songs of which provide the closing set on this album (disc 2, tracks 16–18). Filmed in part in the rubble of post-World War II Berlin, A Foreign Affair blurs the cinematic boundaries between documentary film and feature-length musical film. The cruel realities of war and destruction lie in “the ruins of Berlin,” but the film itself weaves comedy and film noir together. Billy Wilder and Friedrich Holländer return to Berlin from exile once again to play their pre-war roles as film director and cabarettist. The music mixes the diegetic and the non-diegetic in complex ways. Holländer is playing, but so are Marlene Dietrich and Holländer’s fellow musicians in the Hotel Eden Syncopators on the cabaret stage. The American congressmen who are to report on conditions in Berlin after its defeat in World War II arrive to the music of a military band at Tempelhof Airport, reminiscent of army newsreels of the day. Throughout the film, mirrors are used to project images of the real and reflected — ruins and illusions (disc 2, tracks 17 and 18) — a standard technique of film noir. Upon completing A Foreign Affair, Holländer and Wilder were to pursue their own dreams in quite different ways. Holländer rediscovered his métier on the German cabaret stage and spent the remainder of his life performing before live audiences. Wilder, who had returned to Berlin in part to search for remaining traces of family members — among them his mother, who had disappeared in the Shoah — returned to Hollywood, where he would be a critical player in subsequent golden eras of American cinema.

The historical counterpoint formed by the utopia and dystopia of the Shoah rarely yielded to the resolution of return. Return to the Berlin he had left in 1933 led Hanns Eisler into a world of unresolved dreams of utopia and nightmares of dystopia. We witness the failure of resolution — of dreams falling apart — in the stark reality of the film that acts as the closing chapter and coda in the golden age of Jewish stage and film music, Alain Resnais’s 1955 Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog), for which Hanns Eisler composed the musical score. Nuit et brouillard was the first documentary film to return to the concentration camp at Auschwitz. To portray Auschwitz and create a narrative for it, Resnais exaggerated the documentary character of the filming. All subjectivity was stripped away in order to lay bare its subject, the Shoah and its accompanying mass murder.

Resnais employed a remarkable range of documentary film techniques, weaving them contrapuntally into the film: black-and-white (for Nazi Germany in the past) vs. color footage (for shots of Auschwitz in 1955); newsreels mixed with documentary stills taken by the Nazis; and a matter-of-fact tone in the voice-over. Musical intertextuality in the film, for example, in the title’s use of Nacht und Nebel (night and fog in German) as a reference to the Tarnhelm Spell in Richard Wagner’s Rheingold and to portray concentration-camp prisoners who were swept away “under night and fog” to be killed without a trace. Utopia and dystopia struggle and collapse as past and present narrate object lessons for the future. Hanns Eisler employed experimental music in the film, but also covered many of his earlier works. Musically, the film returned to the dreams of an earlier era, exposing their fragility and the tragedy that resulted from too often believing them to be real. In the mirrors of history, dreams fall apart, and we witness their horrible beauty in the closing moments of the golden era of Jewish stage and film music.

Album Details

Total Time: 96:00

Producer: Jim Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio at WFMT Chicago. March 10, 11, 13 & 14, 2014

Cover Art: Caricature of Hermann Leopoldi courtesy of the Leopoldi Society

Booklet & Inlay Card Design: Nancy Bieschke

©2014 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 151