| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

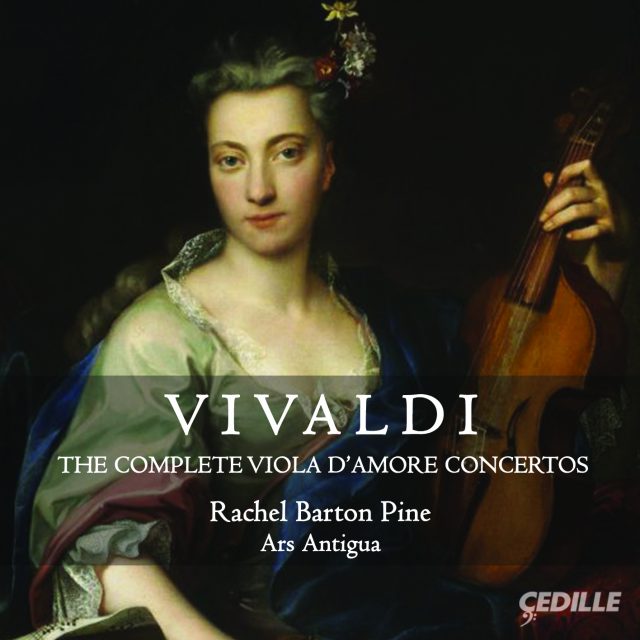

The seductively charming sound of the Baroque-era viola d’amore takes center stage in this new, all-Vivaldi recording with Billboard classical chart-topping violinist Rachel Barton Pine and the veteran Chicago-based period instrument ensemble Ars Antigua, making its Cedille label debut. Pine, Cedille’s all-time best-selling artist, and Ars Antigua perform all eight of Vivaldi’s virtuosic concertos for viola d’amore, an unusual instrument of the violin family with 12 strings: six played with the bow, the others resonating passively for a sweet, silvery tone. In reviewing a program that Pine and Ars Antigua performed at the Chicago Humanities Festival, the Chicago Tribune praised Pine’s “deft, stylish playing” of her 1774 Gagliano viola d’amore. “In everything, the spirit and sensitivity of Barton Pine’s playing were informed by her mastery of the instrument’s intricate technical demands. As much could be said of the alert contributions of her colleagues.”

Rachel Barton Pine is “one of the rare mainstream performers with a total grasp of Baroque style and embellishment” (Fanfare) and “a most accomplished Baroque violinist, fully the equal of the foremost specialists (Gramophone). Founded in the early 2000s by double-bass virtuoso Jerry Fuller, Ars Antigua (“ancient art” in Medieval Latin) comprises seasoned early music veterans from the Chicago area. Pine’s period-instrument discography on Cedille Records includes six acclaimed albums with her ensemble Trio Settecento: Handel Sonatas for Violin and Continuo, An Italian Sojourn, A German Bouquet, A French Soirée, An English Fancy, and the recently released Veracini: Complete Sonate Accademiche. She has performed with her trio colleagues (cellist/gambist John Mark Rozendaal and harpsichordist David Schrader) at New York’s Frick Collection, the Boston Early Music Festival, the Indianapolis Early Music Festival, Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., Houston Early Music, and elsewhere.

Preview Excerpts

ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678—1741)

Concerto in D major, RV 392

Concerto in D minor, RV 393

Concerto in F major, RV 392

Concerto in D minor, RV 394

Concerto in D minor, RV 395

Concerto in A major, RV 396

Concerto in A minor, RV 397

Concerto in D minor, RV 540*

Artists

22: *Hopkinson Smith, lute

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Complete Viola d’Amore Concertos

Notes by Paul V. Miller

On August 25, 1717 in Cento, Italy, Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) performed on an instrument that was evidently just as unusual then as it is now. According to an eyewitness, the instrument in question was “a special kind of twelve stringed viola called the viola d’amore.”[1] Six of the strings would have been playing, and six resonating. This kind of instrument was not new to him. Records indicate that in 1708 and 1709 Vivaldi was reimbursed for providing viola d’amore strings at the Pietà in Venice, his regular job at a school for orphaned and abandoned girls. Vivaldi’s association with the viola d’amore might have gone back even further. In 1689 he probably had his first chance to play it when he met a certain Nicolo Urio at San Marco. Urio was known to play the d’amore. One of Vivaldi’s last works, the D minor double concerto, RV 540, is for viola d’amore and lute. In his long relationship with the viola of love, Vivaldi not only wrote eight concertos for it, but also worked it into several vocal pieces.

What was it about this curious instrument that captured Vivaldi’s imagination? The viola d’amore is an intriguing conglomeration of Eastern and Western ideas. Borrowing resonating strings from the East and mounting them on what is essentially a treble viol altered for playing under the chin like a violin, the viola d’amore allows for great virtuosity while producing a shimmering, halo-like tone. The resonating strings, usually made of wire, go through the bridge, continue through a tunnel underneath the fingerboard, and usually enter the pegbox from behind. Although Praetorius knew of an instrument like the viola d’amore as early as 1619, the English diarist John Evelyn first mentions it by name in 1679, writing that he had “never heard a sweeter instrument or more surprising.” Confusion arises in the 17th century because some instruments with resonating strings were more like the treble viol, whereas others called “viola d’amore” lacked resonating strings. By the time of Bonanni’s Gabinetto Armonico (Rome, 1723) the viola d’amore almost certainly had a set of resonating strings underneath the playing set. From then on, the instrument was associated with the unusual additional strings.

Unlike the violin, no standard approach to building the instrument ever gained dominance; so every instrument is a testament to the builder’s ingenuity and skill in solving a challenging set of problems. Although Stradivarius sketched plans for building one, he apparently never followed through. Our best period examples come from Gagliano, Eberle, Schorn, Stadelmann, Lambert, and others. The instrument fell out of favor in the 19th century because its tone was not loud enough to hold its own against a large orchestra, and it was hard to keep in tune. In the 20th century, virtuosi like Henri Cassadesus and Paul Hindemith rediscovered the instrument and musicians such as Carl Zoeller, Louis van Waefelghem, Karl Stumpf, and Jan Kral tried to prod it into the modern virtuoso tradition, even though no such tradition really existed. At the same time, amateur players such as the novelist Thomas Mann picked it up. Composers such as Puccini, Massenet, and Pfitzner incorporated the d’amore into their operas while Janáček tried and failed to work it into his second string quartet (in place of the standard viola). After World War II, more resonant instruments closer to the specifications of the 18th century won favor. Since then the d’amore has enjoyed a certain renaissance thanks to the efforts of players such as Thomas Georgi, Garth Knox, and now Rachel Barton Pine.

However many twists and turns the viola d’amore took through history, there is no doubt that the cornerstone repertoire for the instrument, at least in the concerto realm, lies with Vivaldi. In the Pietà, concertos on unusual instruments such as the viola d’amore were popular. As Charles de Brosses wrote, “[The girls] play the violin, the recorder, the organ, the oboe, the cello, the bassoon; in short, there is no instrument large enough to frighten them.”[2] Michael Talbot opines that Vivaldi dedicated two of his d’amore concertos to a Pietà student and longtime collaborator, Anna Maria. According to Talbot, by spelling “Amore” as “AMore” in the headings of the concertos RV 393 and 397 Vivaldi alludes to her name. But Vivaldi also brandished a keen and sometimes hard-selling business style. In addition to the concertos he sold, he often induced patrons to take lessons from him. The “Red Priest,” as he was known (for his red hair), clearly recognized not just the musical possibilities of the d’amore but also the commercial value he could realize from teaching an unusual instrument. Because of the instrument’s scordatura tuning, which usually includes one string placed between an open fifth, filling in the triad, (e.g. D3 – A3 – D4 – F#4 – A4 – D5) certain chords and barriolage effects were possible on it that would not be idiomatic on a traditional violin. Vivaldi consistently exploits these effects to good effect in his concertos.

The F Major concerto, RV 97, has the most unusual scoring of the eight. A representative of the so-called “chamber concerto,” Vivaldi scored the work for two oboes, two horns, bassoon, and continuo. There are some 20 Vivaldi concertos of this type written after 1716–1717, when the Saxon Elector Friedrich Augustus (1696–1763) made a trip to Venice, bringing many accomplished musicians in his entourage. The ingenious mixture of wind instruments with the viola d’amore creates many unusually colorful moments in the orchestration. Ever sensitive to the overall ensemble balance, Vivaldi indicated that the oboes and horns should be muted, a problem for which each individual player must devise his or her own solution. RV 97 is the only one of these concertos to begin with a slow introduction, which includes echoes of the French overture style in the bassoon part. The d’amore remains silent as Vivaldi launches the first solo section of the subsequent Allegro, allowing the horns to take center stage; the more chromatically agile woodwinds get their due in subsequent solo sections. The middle movement treats the viola d’amore and oboe as equals in a trio sonata texture, while the bassoon provides the bass line alone. The full instrumental forces return in the finale, where the opening motive clearly relates back to the first movement. By no means is the viola d’amore always the center of attention; in fact, the way the instruments are deployed is reminiscent of Bach’s first Brandenburg Concerto, although obviously on a smaller scale.

The D Major concerto, RV 392, sets the basic pattern for the others: a string orchestra accompanies the solo instrument, and clearly delineated ritornelli involving the entire orchestra alternate with passages in which only a small subset of the ensemble accompanies the soloist. In certain places, Vivaldi indicated that only the cello should play the continuo line, providing evidence for a nuanced approach to deploying the bass instruments. The score of the D Major concerto is in Dresden, and exists only in a copy of Vivaldi’s original manuscript. It might have been brought to Dresden by Johann Georg Pisendel (1687-1755), one of the great violinists of the 18th century who knew Vivaldi and shared his enthusiasm for the viola d’amore. Opening with a cheerful first movement, the second veers away towards B minor and explores a more lyrical style. The finale takes advantage of the d’amore’s ability to play narrow double stops rapidly and accurately, building to a climax in the final solo section where many unison double stops brighten the color of the sound.

The next three concertos — RV 393, 394, and 395 — are all in D minor. Their manuscripts can be found in Turin and are part of a large collection acquired in the early 20th century from the Salesian monks of the Collegio San Carlso in Monferrato.[3] The first movement of RV 393 calls for different accompanying forces in each of the solo sections: first, the viola d’amore plays against unison violins, then after the intervening ritornello the continuo alone accompanies. The haunting third and final solo section returns to unison violins as the accompanying part. Vivaldi chose this strategy not only to build a symmetrical structure but also because it was easy and quick to write just one part against the solo line. The third movement includes more elaborate orchestral accompaniments and a rare case of a written-out Vivaldi cadenza over a dominant pedal (another example is the violin concerto Il Grosso Mogul, RV 208a). The concerto RV 394 includes a lovely middle movement in the siciliana style, with a full four-part orchestral accompaniment. The last movement includes an opportunity for the soloist to execute a cadenza just before the da capo, but Vivaldi does not proscribe anything specific, writing only a fermata and leaving the rest up to the soloist’s imagination. The third D minor concerto of this set, RV 395 (which Vivaldi later reworked into the violin concerto RV 770), seems to play overtly with the idea of the cadenza and its place and in the concerto. At the end of its opening movement, the soloist almost launches into a cadenza at the customary place over the dominant chord at the end, but soon defers, guiding the orchestra back to the final ritornello. Two middle movements exist for this concerto. The original one, marked Largo, contains many chords for the viola d’amore that are impossible to execute on the violin. The Andante alternative features gentle triplet figures idiomatic to either violin or viola d’amore, and takes the unison accompaniment idea to its extreme by having the entire orchestra play the same notes in different octaves. The concerto’s third movement again teeters on the brink of a full-out tonic-key cadenza at the end, but after a tense moment the soloist again leads back to the ritornello. This concerto might leave one with the impression that the solo part fails in some way, but it seems Vivaldi was after a more tense and dramatic confrontation between soloist and orchestra.

If the D minor concertos are more serious in character, the A major concerto, RV 396, opens into a world of sunny cheer, epitomizing Vivaldi’s best-loved qualities as a composer: an effortless flow of ideas, simplicity of means, and appealing clarity of orchestration. This is the only concerto where the solo part is notated in alto clef, which Michael and Dorothea Jappe rightly point out was usually used to indicate scordatura; if this were the case, however, an unusual key signature would be necessary, which Vivaldi never used.[4] Instead, the viola d’amore part is read an octave higher than written in order for its sound to hold up to the orchestra. Because of this, the A major concerto lies relatively high on the instrument. The first movement ends in a brilliant flurry of 16th-note triplets, while the second movement steps back into a more contemplative, lyrical mood. The finale includes a series of up-bow staccatos, a technique that requires a high level of coordination between the hands.

Copies of the A minor concerto, RV 397, exist in Turin and Dresden, although the scores differ in a few places. Unlike in any of the other viola d’amore concertos, the solo instrument has a slightly different part than the orchestra in the opening ritornello, adding extra intensity to the throbbing chords. The second movement showcases the lower reaches of the d’amore, demanding a mastery of perilous string crossings. In the finale, the use of the Neapolitan chord (bII) along with its characteristic diminished-third voice-leading lends an unusual quality not explored fully in any of the other concertos.

Probably one of the last pieces Vivaldi wrote, and almost certainly his last manuscript, the D minor double concerto for lute and viola d’amore, RV 540, is one of many Vivaldi concertos for more than one instrument. The manuscript is a presentation copy, given to the Saxon prince-elector Fredrick Christian when he visited Venice in 1740. The use of mutes in the orchestra indicates Vivaldi’s awareness of the danger that the orchestra could overpower the soloists (especially the lute), but the solo instruments make a natural pairing as the shimmering quality of the d’amore matches well with the lute. J.S. Bach also used this combination to his advantage in the viola d’amore arias of his Johannespassion , BWV 245. The first and third movements involve a number of witty dialogues between the solo instruments. In the middle movement, the lute accompanies the viola d’amore along with a single unison violin part.

After Vivaldi, the viola d’amore went on to enjoy a somewhat prominent place as an auxiliary instrument in the 18th century. Telemann wrote an appealing triple concerto for viola d’amore, flute, and oboe d’amore; and the works of Atillio Ariosti form the bedrock of its 18th century sonata repertoire. Later in the century, music by Franz Götz, Anton Huberty, and Johann Stamitz proved that the instrument was adaptable to the Classical style. Nevertheless, Vivaldi’s works have never been displaced from their spot at the front of the catalog of viola d’amore music: their variety, wit, and grace have inspired many generations of violinists and violists to pick up what often seems at first a wholly impossible instrument to play. Mattheson’s statement that the viola d’amore “fulfills its lovely name . . . and has a most languishing and tender effect” still rings true today.

Paul V. Miller is a scholar and performer of modern and baroque music. His research has been published in Perspectives of New Music, Music and Letters, and Twentieth-Century Music, and he has taught at Temple University, the University of Colorado in Boulder, and Cornell University. He has also performed the viola d’amore at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Library of Congress and National Cathedral in Washington, DC.

[1] Bolletino dell’Istituto Italiana Antonio Vivaldi, No. 20 (Milan: Ricordi, 1999), p. 137.

[2] Le president De Brosses en Italie: lettres familières écrites d’Italie en 1739 et 1740, ed. R. Colomb, vol. I (Paris, 1858), p. 194.

[3] Michael Talbot, Vivaldi (New York: Schirmer, 1992), p. 5.

[4] Michael and Dorthea Jappe, Viola d’Amore Bibliographie (Winterthur: Amadeus Verlag, 1997), p. 192.

Album Details

Total Time: 79:11

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Editing: Jeanne Velonis

Recorded: November 15—16, 2011 (RV 392—395), July 1, 2, 8, and August 27, 2014 (RV 97, 396, 397 & 540), Nichols Hall at the Music Institute of Chicago

Graphic Design: Nancy Biescke

Cover Art: Woman with a Viola d’Amore (Portrait of Maria Helena Sabina Imhoff?), Jan Kupecky (1720s), oil on canvas, used with permission from the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest

Viola d’amore: Nicola Gagliano, 1774

Viola d’amore bow: Chris English

Viola d’amore strings: Daniel Larson

© 2015 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 159