| Subtotal | $54.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $5.55 |

| Total | $59.55 |

Store

Store

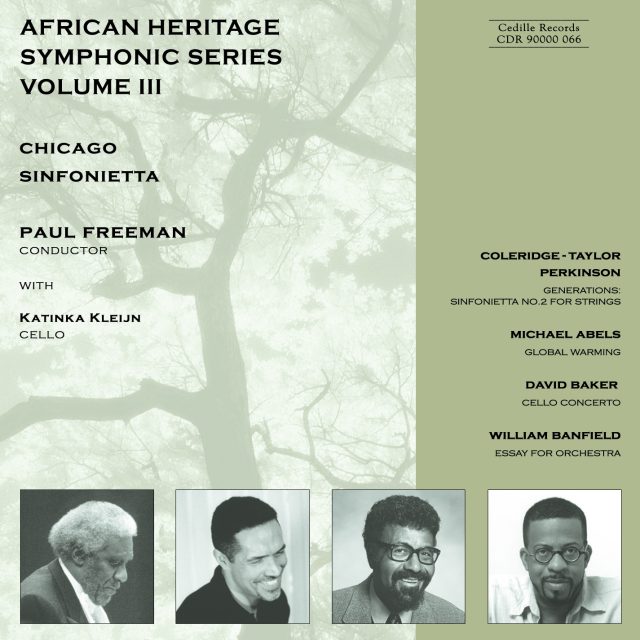

African Heritage Symphonic Series – Vol. III

Chicago Sinfonietta, Paul Freeman

Katinka Kleijn, Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, Michael Abels

Works by four leading Black American composers comprise the third and final installment of Cedille Records’ acclaimed African Heritage Symphonic Series. Volume III features compositions from the last quarter of the 20th century performed by the Chicago Sinfonietta led by maestro Paul Freeman, “one of the finest conductors our nation has produced” (Fanfare). Freeman spearheaded the landmark Black Composers Series of Columbia LPs in the 1970s, which inspired the new undertaking.

Renowned composer David Baker (b. 1931) performed and recorded as a jazz trombonist with Quincy Jones, Maynard Ferguson, and Lionel Hampton. He later became enamored of the cello but never abandoned his jazz roots, as his evocative and highly virtuosic Cello Concerto (1975) beautifully demonstrates. Soloist on the CD is the noted young Chicago Symphony Orchestra cellist Katinka Kleijn.

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932-2004) studied with Earl Kim at Princeton and with expatriate African American conductor Dean Dixon in the Netherlands. He co-founded New York’s Symphony of the New World and composed a tribute to Charlie Parker for the Alvin Ailey dance company. Perkinson’s Generations: Sinfonietta No. 2 for Strings (1996) draws on a wide range of influences, displaying the composer’s musical wit and uncommon ability to transform familiar melodies.

William Banfield (b. 1961) is probably the most noted figure among the younger generation of African American composers. His music echoes his belief that the juxtaposition of styles in pop music has prepared listeners for similar explorations in art music. That credo is particularly evident in his eclectic, percussion rich Essay for Orchestra (1994). One conductor called the piece “. . . a huge, Wagnerian Jazz Romp.”

A genuine rising star, Los Angeles-based composer Michael Abels’s (b. 1962) Global Warming (1990) has multiple meanings. Its opening passage suggests a vast, arid desert, but it soon moves on to lively Irish and Middle Eastern sounding themes. The jaunty congruence of these culturally disparate sounds connotes a very different kind of “Global Warming.” The piece has received more than 100 performances and was the first work by a Black composer to enter the repertory of South Africa’s National Symphony.

Preview Excerpts

MICHAEL ABELS (b. 1962)

DAVID BAKER (b. 1931)

Cello Concerto

WILLIAM BANFIELD (b. 1961)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON (1932-2004)

Generations: Sinfonietta No. 2 for Strings

Artists

2: Katinka Kleijn, cello soloist

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAfrican Heritage Symphonic Series - Vol. III

Notes by Dominique-René de Lerma

The quartet of composers represented here have a particular distinction in common: Each displays remarkable stylistic versatility, working not just in concert idioms, but also in film music, gospel music, and jazz.

Michael Abels was born in 1962 in Phoenix, Arizona, where he also attended grammar school. He spent his youngest years, however, in rural South Dakota and began studying piano there at an early age. A graduate of the University of Southern California, he studied composition with James Hopkins and Robert Linn and was named Outstanding Senior among student composers for his “Queries” for piano and prepared piano. In 1985–86, Abels studied West African music with Alfred Ladzekpo at the California Institute for the Arts. Abels remains a resident of Los Angeles.

Abels wrote Global Warming in 1990, not long after the Berlin Wall fell. It attracted international attention when it was featured at the Detroit Symphony Orchestra’s 1992 African-American Symphony Composers Forum and has enjoyed more than 100 performances since its debut. Most notably, Global Warming became the first piece by a Black composer to enter the repertory of the National Symphony of South Africa.

Abels has stated that “living in Los Angeles, I’ve been able to learn about music from around the world simply by opening the window; among my neighbors are immigrants from every corner of the world. I was intrigued by the similarities between folk music of divergent cultures, and decided to write a piece that celebrates these common threads as well as the sudden improvement in international relations that was occurring.” The title Global Warming seemed suitable for the incorporation of these ideas. It was commissioned by the Phoenix Symphony Guild and first performed by the Phoenix Youth Symphony in 1991, with conductor Mark Russell Smith. Abels describes the work as follows:

The opening section of the piece is a vision of the traditional idea of global warming — a vast desert, the relentless heat punctuated by the buzzing of cicadas, and an anguished, frenetic solo violin (with help from a solo cello). This scene gives way to several episodes reminiscent of folk music of various cultures, most noticeably Irish and Middle Eastern. At the climax of the piece, a Middle Eastern melody is transformed, through gradual changes in rhythm and ornamentation, back into the Irish refrain, and many counter-melodies join in to present a noisy — yet harmonious — world village. This joyous moment is broken by a sudden return to the stark vision of the opening, leaving the listener to decide which image may more accurately reflect our future.

Among Abels’s other works is Tribute (2001), a short DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 orchestral memorial to the events of September 11. He has also written works for chorus, two operas, and other compositions for orchestra, many created on commission. His output manifests an interest in sports (he is a triathlete) and his dedication to outreach projects, with particular concern for social welfare and for young people. Abels ascribes to the philosophy of many contemporary artists of color who see international implications inherent in their ethnic heritage.

Born in Indianapolis in 1931, David Baker spent the first part of his remarkable career as a jazz musician. Baker’s undergraduate and graduate studies were at Indiana University, where he is now a Distinguished Professor and chair of the jazz department. His original intention to become an orchestral trombonist was short lived — orchestral work was more or less out of reach for African Americans at the time — so Baker entered the jazz world. He enjoyed rapid success, performing and recording in the U.S. and Europe with several jazz legends including Quincy Jones, George Russell, Maynard Ferguson, and Lionel Hampton. An accident put an end to Baker’s trombone playing in 1966. That same year, he joined the faculty at Indiana and began training a new generation of jazz musicians. Baker then took up the cello, studying with faculty colleague Janos Starker.

In 1968, Baker’s interest in liturgical jazz produced a blockbuster: a massive memorial to Martin Luther King Jr., in which an orchestra of cellos appears amid several other ensembles. Over the next two years he wrote a violin concerto (for Joseph Gingold) and a flute concerto (for James Pellerite), both featuring jazz band accompaniment. Baker described his next concerto, completed in 1975 and dedicated to his cellist colleague, Starker, as follows:

The first movement is lyrical in nature, featuring the cello in a somewhat transparent environment, ending with harmonics. The second movement opens with an extended solo cello recitative in which all of the principal thematic material of this movement is presented. The first theme is reminiscent of the material from the first movement; and special effects, including glissandi in the upper strings and the use of exotic percussion, create an impressionistic atmosphere. The third movement is jazz-influenced. The first theme uses the harmonic progression from Back Home Again in Indiana and is introduced over a series of rhythmic interjections. The second theme is a clever and charming twelve-tone row conceived by Starker and incorporated into this movement over a rhythmic bass line.

There is one particularly remarkable feature about the instrumentation of Baker’s Cello Concerto: the orchestra itself contains no cellos.

Since 1975, Baker has written several more works for Starker, including Ode to Starker, for an orchestra of cellos, unveiled at a surprise birthday gala for the cellist in 1999.

Baker’s talent and hard work have won him endless awards (including the Jazz Education Hall of Fame award, the Arts American Jazz Masters Award, and nominations for both the Pulitzer Prize and the Grammy Awards), commissions (including from the New York Philharmonic, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, the Beaux Arts Trio, and the Fisk Jubilee Singers), and appointments (including to the National Council on the Arts, as Senior Music Consultant for the Smithsonian Institution, and to panels with the National Endowment for the Arts and for the Kennedy Center). He continues to write jazz compositions regularly, and also remains a prolific publisher of scholarly essays on jazz greats and manuals for jazz students.

Born in 1961, William C. Banfield secured his initial education in his hometown of Detroit, where he graduated from Cass Technical High School in 1979. Banfield began learning guitar at the age of eight, eventually winning a grant from the Chrysler Corporation, which he used for study in Acapulco. He majored in guitar at the New England Conservatory of Music, earning his B.M. degree in 1983. In his final undergraduate year, Banfield studied composition with T.J. Anderson at Tufts University, and with Michael Gibbs at the New England Conservatory. From 1985 to 1987, Banfield continued his composition studies with Theodore Antoniou at Boston University, while obtaining his M.A. degree in theological studies. From 1988 to 1992, Banfield pursued his D.M.A. degree at the University of Michigan, where he worked with composers William Albright, Leslie Bassett, Fred Lerdahl, and William Bolcom.

During his student years, Banfield maintained an intense schedule as a performer and conductor of various ensembles in Boston, Detroit, and Sénégal, and also taught. From 1992 to 1997, he served on the faculty of Indiana University and also held visiting residencies at the University of St. Augustine college, Duke University, and the University of Texas, Austin. Leaving Indiana University in 1997, Banfield accepted the endowed chair in Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he currently serves as Associate Professor of Music and director of American Cultural Studies. In 2000–2001, he was a W.E.B. Dubois fellow at Harvard University, completing two operas. In 2002, Nobel Prize winning author Toni Morrison invited Banfield to Princeton University as a visiting Atelier artist.

Banfield’s impressive list of symphonic commissions began with one from the Detroit Metropolitan Orchestra in 1983. Since then he has had works commissioned and performed by the Washington D.C. National Symphony and the symphonic orchestras of Detroit, Dallas, San Diego, Sacramento, Savannah, Grand Rapids, Atlanta, Indianapolis, Richmond, and Minnesota. His catalog contains works for various instrumental ensembles, orchestra, and band, as well as choral music, operas, and songs. He has also penned numerous popular songs and jazz compositions. Guthrie Ramsey’s entry on Banfield in the International Dictionary of Black Composers encapsulates the composer’s aesthetic: Banfield “believes that the juxtaposition of the many styles that comprise the popular music scene today has prepared younger audiences for similar developments in art music.” (Ramsey, Guthrie R., Jr., “Banfield, William Cedric,” in International Dictionary of Black Composers, Volume 1, Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., ed. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1999., pp 66–74.)

About his piece on this CD, Banfield has written:

Essay for Orchestra is taken from a larger work for percussion and orchestra. The movement seemed so well suited as a moving orchestral essay with themes and evocative musical sweeps to be adapted for a short concert piece. It is simply that, an attempt to hear the various orchestral voices interacting. One observer called it “. . . a large 19th-century Romanticism infused with contemporary jazz harmonic and rhythmic sensibilities.

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson was named for the celebrated Afro-British composer, Samuel ColeridgeTaylor. Befitting his name, Perkinson seemed destined for a musical career almost from the moment of his birth in New York in 1932. Perkinson’s mother was a piano teacher in the Bronx who also directed a theater company and played organ for a church choir there. Perkinson studied dancing early on, working under the tutelage of Ismay Andrews and Pearl Primus; but it was his keen musical ear that gained him admission to New York’s prestigious High School of Music and Art, where Perkinson met Igor Stravinsky for the first time (thanks to his mentor, choral conductor Hugh Ross). Perkinson began conducting and composing in high school. Upon graduation in 1949, he won the LaGuardia Prize in music. For the next two years, he majored in education at New York University. He changed course in 1951, however, enrolling in the Manhattan School of Music where he earned his master’s degree in composition (and later taught). His composition teachers there included Vittorio Giannini and Charles Mills. He later worked with Roger Sessions’s assistant, Earl Kim, at Princeton University. Already on the faculty of Brooklyn College (1959–1962), Perkinson went to the Netherlands during the summers of 1960, 1962, and 1963, where Franco Ferrara and the African American expatriate, Dean Dixon coached his conducting. Perkinson also pursued conducting studies at the Mozarteum in Salzburg later in the summer of 1960.

In 1965, he co-founded New York’s Symphony of the New World, and later became its Music Director, a title he has also held with Jerome Robbins’s American Theater Lab and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. More recently, Perkinson was a guest lecturer at Indiana University, and has been Coordinator of Performance Activities at Columbia College’s Center for Black Music Research since 1998.

The performances of Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach, and Perkinson’s own contacts with fellow Manhattan School of Music students Max Roach, Julius Watkins, Herbie Mann, and Donald Bird, led Perkinson to make a detailed study of the music of the highly influential jazz great Charlie “Bird” Parker. The most palpable result of this interest was Perkinson’s ballet For Bird, With Love, composed for Alvin Ailey’s dance group.

Perkinson’s compositions range from unaccompanied solo instrument to works for chorus and orchestra. He has also worked as a composer, arranger, and supervisor of recordings by many pop figures, including Marvin Gaye. He has served as a panelist on campuses throughout Europe and America, and has been conductor and/or featured composer with numerous orchestras. Most recently, his Symphony of the Sphinx, with a text by Nikki Giovanni, was commissioned by Michigan’s TexacoSphinx Competition (2002). He has also composed and conducted music for several films, including the Martin Luther King documentary Montgomery to Memphis, and A Warm December, starring Sidney Poitier. Perkinson wrote Generations: Sinfonietta No. 2 for Strings in 1996 on a commission by Michael Rudiakov and the Manchester Music Festival. The score bears the following words by the composer:

The inspiration for this composition, though non-programmatic, is somewhat autobiographical in that it represents my attempts at what were and are my relationships to members of my family — past and present. While each of the movements is without a strict “formal” mode, an informal analysis of their structures is as follows:

I. Misterioso and Allegro (to my daughter) is based on two motifs: the B-A-C-H idea (in German these letters represent the pitches Bflat, A-natural, C-natural, and B-natural), and the American folk tune “Mockingbird,” also known as “Hush Li’l Baby, Don’t Say a Word.”

II. Alla sarabande (sarabande, a 17th- and 18th-century dance in slow triple meter) is dedicated to the matriarchs of my immediate family (of which there were for me, three), each of whom contributed a unique form of guidance for life’s journey.

III. Alla Burletta (to my grandson). A burletta is an Italian term for a diminutive burlesca or burlesque-type work — a composition in a playful and jesting mood. Thematically, this movement is based on the pop tune “Li’l Brown Jug.”

IV. Allegro vivace. This movement is a loosely constructed third rondo which thematically begins with a fughetta (original melody), has a second theme (African in origin), and a third theme (“Mockingbird” paraphrased). Once

again, the B-A-C-H idea from the first movement is the musical thread that ties these elements together. This movement is dedicated to the patriarchs of my family, known and unknown, past, present, and future, for generations.

Album Details

Total Time: 58:45

Recorded: May 21 & 23, 2002 in Lund Auditorium at Dominican University, River Forest, IL

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Front Cover Photographs: “Acacia Tree, Africa” by Stuart Westmorland © The Image Bank. Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson photo courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research, Chicago IL. William Banfield photo by Andy Marino. Michael Abels photo by Rick Castro

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Dominique-Rene de Lerma

Sara Lee Foundation is the exclusive corporate sponsor for African Heritage Symphonic Series, Volume III. This recording is also made possible in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts & The Aaron Copland Fund for Music.

©2002 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 066