Store

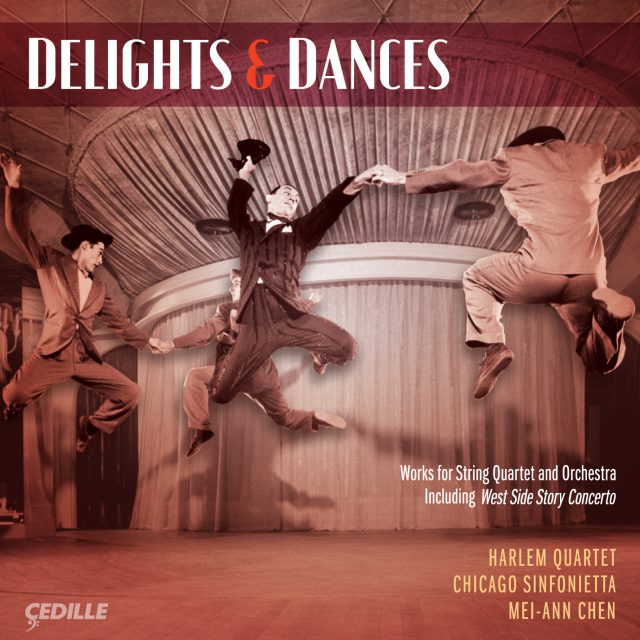

Delights & Dances, the Chicago Sinfonietta’s first recording with its new music director, award-winning conductor Mei-Ann Chen, does what this singular ensemble does best: it captivates listeners of all ages and diverse ethnic backgrounds through irresistible music and superb musicianship. On Delights & Dances, the Chicago Sinfonietta, a standard-bearer for racial diversity in the orchestral world, works its magic through a one-of-kind program featuring music for string quartet and orchestra, with guest artist, the Harlem Quartet.

The album takes its title from Michael Abels’ witty, soulful, and infectiously rhythmic Delights & Dances, which receives its world premiere recording. The greatly admired contemporary African-American composer wrote the work for the Harlem Quartet, an ensemble of first-place laureates of the Sphinx Competition for outstanding young black and Latino string players. A New York Times review of the work’s 2007 premiere, presented at Carnegie Hall, described the piece as “an energetic arrangement . . . which incorporates jazz, blues, bluegrass and Latin dance elements” — and which the Harlem Quartet “played with panache.”

Preview Excerpts

MICHAEL ABELS

BENJAMIN LEES

Concerto for String Quartet and Orchestra

AN-LUN HUANG

LEONARD BERNSTEIN arr. RANDALL CRAIG FLEISCHER

West Side Story Concerto for String Quartet and Orchestra

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDelights and Dances

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The incomparable PDQ Bach— better known as composer and classical music comedian Peter Schickele—once wrote a Concerto for Two Pianos vs. Orchestra. The spoof reflects on what would happen if a pair of virtuoso soloists decided to show off with no regard for what the orchestra was playing; and if the orchestra then decided to show off with no reference to what the soloists were doing. It’s hilarious in performance, but it ignores the principle of concerto writing: the term comes from the Latin word “concertare,” which means “to sing together.”

Our image of a concerto today posits a single soloist in front of an orchestra, pouring out beautiful solo melodies. Of course, these melodies would be far less impressive without the contributions of all the supporting musicians. In the 17th and 18th centuries, when concertos originated, they were quite different, calling for a small group of soloists trading themes with a slightly larger ensemble, about the size of a modern chamber orchestra. This genre, known as the Concerto Grosso, was practiced by Handel, Telemann, Corelli, and many of their contemporaries. Bach composed the concerti grossi most often heard today: the six Brandenburg Concertos. He was also a pioneer of the solo concerto, having borrowed and expanded on the example of Antonio Vivaldi, who wrote hundreds of concertos featuring a single soloist, although he also composed some of the concerto grosso variety.

In the 19th century, with the solo concerto firmly established as the preferred musical idiom, only a few composers carried on the concerto grosso tradition. Ludwig Spohr was one; England’s Sir Edward Elgar composed his Introduction and Allegro for solo string quartet and string orchestra; and in the first half of the 20th century, prolific Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu created several works of the concerto grosso variety. On this album, the Chicago Sinfonietta compiles three recent examples of this type of work, showcasing the virtuosity of the Harlem Quartet, which performed these works with the Chicago Sinfonietta under the leadership of music director Mei-Ann Chen in concert prior to their recording sessions.

Michael Abels composed his Delights & Dances for string quartet and string orchestra specifically for the Harlem Quartet. Born in 1962 in Phoenix, Arizona, Abels studied composition at the University of Southern California. Along with the standard curriculum, he explored his African-American roots by studying gospel music and African drumming. Abels received two Meet the Composer (now New Music USA) grants, one allowing him to work with young musicians through the Watts Tower Arts Center in Los Angeles, the other providing a residency with the of Richmond Symphony (VA) and its youth orchestra. His works include the 1997 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. tribute Dance for Martin’s Dream and 1991 composition Global Warming, which is not just a reference to climate change, but also to the thawing of international relations Mr. Abels hoped for after the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

Delights & Dances, a single-movement work, often features rapidly-paced chord patterns and 16th-note runs for the solo quartet. These are rhythmically varied by the insertion of triplet patterns, which tend to relax and slow down the pace.The introductory section commences at a measured pace, Largo, with the further notation, molto rubato, indicating rhythmic freedom. Indeed, the opening passage for solo cello sounds almost like a cadenza. The solo viola picks up the cello’s ascending seven-note motive and they combine in a short duet, joined soon by the two solo violins. When the orchestra enters, it plays pizzicato, in short, detached, syncopated patterns. This “Bluesy” first section has the smokey sound you would expect, but still manages to feel upbeat and rhythmic. The blues theme is reintroduced by the solo cello, then viola and violins, and finally as a solo for the first violin. Each instrument in the solo group gets its own riff, and for the first time we hear the orchestra playing bowed strings. The final section, “Bluegrassy,” begins with the theme in the solo viola part, but soon all four soloists are engaged in a lively hoedown. Eventually, the solo quartet and the strings of the orchestra are united in a grand unison tutti for a full-throttle, upbeat conclusion.

Born Benjamin George Lisniansky in 1924, American composer Benjamin Lees (d. 2010) came from Russian-Jewish parents who settled in San Francisco after Lees was born in China. He served briefly in the U.S. Army during World War II. After the war, Lees studied composition at the University of Southern California, where his teachers included Halsey Stevens. His most fruitful student-teacher relationship, however, was with the iconoclastic American George Antheil. In a conversation with musical commentator and record reviewer Martin Anderson, Lees recalled, “George never considered himself a teacher per se. His role was one of analyst…. It was a true master-apprentice relationship.” Subsequently, Lees received fellowships from the Fromm and Guggenheim foundations, which allowed him to travel and compose in Europe during the 1950s. These experiences encouraged his individualistic approach to music without reference to any prevailing “school” of composition.

Returning to the U.S., he undertook teaching posts at the Peabody Conservatory, Manhattan School of Music, Queens College and, eventually, Juilliard—continuing to compose all the while. Several works were commissioned by the Dallas Symphony: his Symphony No. 4, “Memorial Candles,” a commemoration of the Nazi Holocaust, and Concerto for Brass Choir and Orchestra among them. Lees wrote a similar work for the Detroit Sym-phony, using a wind-solo group. His very first work in this concerto grosso vein was the Concerto for String Quartet and Orchestra of 1964. This work exhibits several Lees trademarks including vigorous rhythmic activity with frequent shifts of meter. Some of the meters in the String Quartet Concerto are unusual, such as 7/8 and 5/4; these tend to make the pulse feel unsettled and more propulsive. Another characteristic is the repeated use of semitone intervals (e.g., C to C-sharp), either as reiterated thematic or accompanimental patterns, or as dissonant chordal strikes.

The orchestral winds and trumpets open the Allegro con brio first movement with just such a passage of insistent semitonal chords. This is virtually a perpetual-motion movement, with little slackening of pace or lightening of texture. The solo quartet enters as a body, with a short, questioning theme. The only brief moment of relaxation comes with a cello solo, curiously marked Calmo ma inquieto (quiet yet restless) — the underlying tension remains even where the sound is momentarily more mellow. Orchestral tutti passages re-introduce the opening chord pattern, this time with the addition of pounding tympani. Another solo cello passage leads to a return of the opening material and an abrupt end.

Andante cantando, the marking for the second movement, means moderately paced with a singing tone. Here the atmosphere is much more relaxed and lyrical, and the solo quartet stands out more from the surrounding orchestral texture. Soft tympani strokes support a sinuous theme for the solo quartet, presented in imitation. A later passage for the solo group unfurls a melody full of semitones. An orchestral climax ensues and is succeeded by a lyrical first-violin solo. The quartet then re-unites to provide a tranquil ending based on diatonic triads, punctuated by high-pitched closing comments from the flute and piccolo.

Launched by brass fanfares followed by rapid figures from the solo quartet, the Allegro energico finale takes us back to the perpetual motion feel of the opening. Musicologist Niall O’Loughlin describes this closing movement as a rondo, typical of Classical era concertos, where a recurring theme is interspersed with contrasting episodes. The overwhelming impression here, though, is of themes and motives tumbled one upon another at a headlong pace, with constant emphasis on those ever-important semitones: as repeated motivic figures or percussive chords. The music sweeps the listener along on a wave of virtuosic sound culminating in a fortissimo final chord.

Mei-Ann Chen and the Chicago Sinfonietta include on this recording an audience favorite, Saibei Dance by An-Lun Huang. Born in China in 1949, a former student at the Beijing Central Conservatory of Music, Huang emigrated to Canada in 1980 and currently resides in Toronto. After emigrating, Huang continued his composition studies in Canada, England, and the U.S. He has forged his own blend of Eastern and Western sounds in compositions for orchestra, stage, and film. Saibei Dance‘s Oriental-inspired opening theme is played first by a solo flute and then picked up by the full orchestra; a similar tune sounds from a clarinet and is likewise enlarged. The string section introduces a new melody, soon combined with the previous ones. Sudden dynamic contrasts, brass fanfares, and prominent percussion punctuate the melodic texture as the full orchestra carries this lively dance to its bright conclusion.

Conductor, composer, and arranger Randall Craig Fleischer says of his West Side Story Concerto: “The challenge for me in crafting this arrangement was to retain everything that is unique about the score, its sensual colors in the love duets, its edgy bite in the gang scenes, the Latin jazz flavor, and transfer all of Bernstein’s unique genius from voices to string instruments.” Fleischer’s rich and vivid scoring echoes the original sound of Bernstein’s 1950s Broadway hit, which updates the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet by transferring the story to the streets of modern-day New York City. A motive that unifies the arrangement is the rising three-note pattern that identifies the song “Maria.” It is an echo throughout, constantly reappearing amid other tunes.

The “Mambo” beginning for full orchestra, dominated by the brass, is contrasted by the gentler “Cha Cha” dance. This leads directly to the solo quartet’s first presentation of “Maria,” characterized by a poignant cello solo. The quartet then harmonizes on the “Tonight” duet, followed by another tutti passage before the quartet launches into the big cadenza. The orchestra returns to play music from the show’s jazzy “Prelude” before introducing the popular “America” theme, which is then varied by the members of the quartet. Next comes the “Tonight” ensemble piece known as the “Quintet.” This contrasts the sounds of the gang rumble with the love song. The sharp juxtaposition of romance and violence echoes this most intense and poignant scene from the show. Fleischer concludes his arrangement with a second cadenza, which returns to “Maria” before introducing the heartbreaking “Somewhere” (“There’s A Place for Us”) as the basis of the work’s touching “Finale.”

Andrea Lamoreaux is Music Director of 98.7WFMT, Chicago’s classical experience.

Album Details

Total Time: 64:10

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: June 19–20, 2012 in Wentz Concert Hall at North Central College, Naperville, Illinois

Cover: Harem Dancers (the Jack Cole Group) performing at the Harem Nightclub in New York City, January 1, 1947; (Photo by Gjon Mili//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Cover Design: Sue Cotrill

Inside Booklet & Inlay Card: Nancy Bieschke

Publishers:

Abels ©2007 Subito Music Publishing

Lees ©1968 Boosey & Hawkes

Huang ©1975 An-Lun Huang

Bernstein/Fleischer ©2011 Boosey & Hawkes.

© 2013 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 141