Store

Not since the LP era of the 1970s has there been anything like Cedille Records’ African Heritage Symphonic Series.

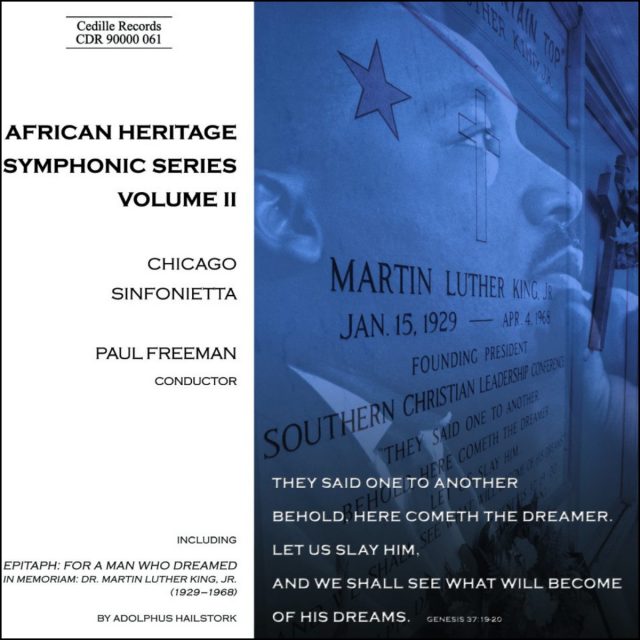

Volume II features compositions by exceptional Black composers from the 1940s to the 1980s, performed by the Chicago Sinfonietta led by its founder and music director, Dr. Paul Freeman,”one of the finest conductors our nation has produced.” (Fanfare)

Ulysses Kay’s ebullient Overture to Theater Set (1968) exudes a broad and good-natured energy. George Walker’s intensely romantic Lyric for Strings (1941) is one of the great gems of the string orchestra repertoire. With his acclaimed Eight Miniatures for Small Orchestra (1948), Panama’s Roque Cordero succeeded in synthesizing the avant-garde techniques he learned in the U.S. with the Latin and Afro-Caribbean music of his homeland. Accented with archetypal African drumming patterns, Hale Smith’s Ritual and Incantations (1974), radiates an aura of mystery and suspense. Adolphus Hailstork’s An American Port of Call (1985) takes the listener on a lush, fanciful, and jazzy excursion. Ten years in the making, Hailstork’s Epitaph for a Man who Dreamed (1979) pays tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King with passages of exquisite tenderness and noble power.

Preview Excerpts

ULYSSES KAY (1917-1995)

GEORGE WALKER (b. 1922)

ROQUE CORDERO (b. 1917)

Eight Miniatures for Small Orchestra

ADOLPHUS HAILSTORK (b. 1941)

HALE SMITH (b. 1925)

HAILSTORK

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAfrican Heritage Symphonic Series - Vol. II

Notes by Dominique-René de Lerma

The history of composition by figures of African ancestry, perhaps still considered exotic, now covers five centuries. Those figures not of American or recent African birth generally wrote music compatible with the style of the times, nuanced by their immediate environment. Those writing for the churches in colonial Mexico or Brazil, for example, were influenced by their Spanish and Italian models but, when engaged in non-liturgical composition, sometimes showed more ethnic characteristics. It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States that individual composers began to assert their cultural legacy. (In Africa, this did not occur until the twentieth.) By transforming spirituals into art songs, and with the emergence of Black musical theater, composers were responding to Dvorák’s call for the development of a distinctly American music, as well as to the inspiration provided by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s visits from England. This was the era of composers such as William Grant Still, Hall Johnson, William Dawson, John Work, Eubie Blake, Duke Ellington, Harry Burleigh, and Florence Price — most of whom secured their education in Black academic circles.

That the time would come for some degree of assimilation was inevitable. Even before the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in favor of school desegregation, a few northern institutions already accepted African American students — Oberlin, the New England Conservatory, and the Curtis Institute of Music are examples. In this atmosphere, the embryonic composer was no longer nurtured on the spiritual and, quite often, not raised on blues or jazz either. An influx of European musicians in the vanguard overtook the influence of distinctly Black idioms. Many African American composers gravitated toward neo-classicism — a style more universal and objective than regional or ethnic. This perspective is exemplified by the music of Ulysses Simpson Kay.

Kay was born in Tucson in 1917. Although this would seem an unlikely place for a large Black population, most of Kay’s elementary school classmates were Black or Mexican. Before he reached his teens, Kay had studied piano and violin, but it was the saxophone that captivated him. He was urged to give the piano no less attention, however, by his uncle Joe in Chicago — better known as the classic jazz musician King Oliver. Despite this family connection, and although he did play jazz when younger, Kay the composer mostly avoided jazz idioms. While an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, Kay received encouragement from William Grant Still. He went to the Eastman School of Music in 1938 for graduate study with Howard Hanson and Bernard Rogers. In the summer of 1941, he studied at the Berkshire Music Center with the ardent neo-classicist, Paul Hindemith. Teaching at Yale University, Hindemith encouraged Kay to continue his studies in New Haven. Though only for the 1941-42 academic year, this was a formidable experience. From then until the end of the Second World War, Kay served as a musician in the Navy. An Alice M. Ditson Fellowship allowed Kay to study under Otto Luening at Columbia University after the war. In 1949, he moved to Rome for yet more study, having won a Fulbright Scholarship, the Prix de Rome, and a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship. Upon his return in 1953, he was engaged by the performing rights organization, Broadcast Music, Inc., with which he remained until 1968. Kay was selected in 1958 by the U.S. State Department to visit the Soviet Union along with Peter Mennin, Roger Sessions, and Roy Harris. In 1968, he was appointed distinguished professor at Lehman College of the City University of New York, retiring after two decades. He died in 1995.

Kay wrote the orchestral suite, Theater Set in 1968 on a commission from the Junior League of Atlanta. The work is dedicated to Robert Shaw, who led the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra in its premiere that September. The good-natured, richly scored overture is in ternary form. March-like fragments at the beginning reappear at the end in new guise, while the middle section presents a contrasting, angular melody. The other two movements of the suite are titled “Ballad-Chase Music” and “Finale.”

Born the same year as Kay (1917) but in Panama, Roque Cordero’s heritage, like that of most of his compatriots, includes African, Spanish, and Native American elements — pretty much the same ethnic background as William Grant Still. Sociology being what it is, however, Cordero is considered a Panamanian composer, while Still is seen as a Black composer.

As a teenager, Cordero was attracted to the popular music of his native country. At age 17, he began thinking about composing, and specifically about creating an idealization of Panama’s folk idioms. At 21, he was appointed director of the Orquesta Sinfónica de la Union Musical and subsequently joined the Orquesta Sinfónica de Panamá as a violist (which, along with the clarinet, he had studied since childhood). Formal training in composition, not then available in his homeland, became possible in 1943 when he received a nine-month scholarship from the Institute of International Education for study at the University of Minnesota. John K. Sherman, music critic for the Minneapolis Star Journal, observed Cordero’s conducting and brought him to the attention of Dimitri Mitropoulos, then music director of the Minneapolis Symphony. Mitropoulos enthusiastically examined the young composer’s first orchestral score and elected to provide funding for four years of study, but at Hamline University in St. Paul. There Cordero could study with Ernst Krenek, whose music Mitropoulos championed. At the time, the student had never heard of Krenek, nor was he familiar with the twelve-tone, or “serial” system of composition in which the teacher was involved.

This concept, as devised by Arnold Schönberg, arranges all 12 pitches into an arbitrary order prior to the start of a composition. By using this tone-row in its original form, backwards, inverted, in retrograde inversion, and in transpositions, the composer has 48 versions for use as melody and harmony. Dr. Cordero has written that while he has been quite willing to employ the technique in his own way, he never used this system in a completely orthodox manner (except in his exercises for Krenek).

William Grant Still was exposed to vanguard techniques when he studied with Edgar Varèse, but pushed those concepts aside when they conflicted with his interest in ethnic expression. Similarly, Cordero would readily eschew the dictates of the serial system when they might interfere with his proud Panamanian nationalism. Nonetheless, Cordero has been fascinated by the possibilities inherent in securing a synthesis of the twelve-tone technique with Panamanian folk idioms.

Despite his patriotism, Cordero has been hesitant to accept the nationalist label without qualification. In Music in Latin America, author Gerard Béhague cites the following quotation:

“If a composer is sincere towards himself and his fellow men … his music (by being his) will present more or less clear national characteristics – rhythmic figures, melodic contours, etc. – without resulting necessarily in local product. In such a case, the author … will create a work with strongly native character but with a spiritual message which communicates to the universe, obtaining thus a national art but not nationalistic in the narrow sense of the term.” (Gerald Béhague, Music in Latin America, Prentice Hall, 1979, p. 261.)

The original version of Miniaturas took shape in 1944, as the composer was beginning to try for a serial/folk synthesis. Cordero revised the suite for a smaller orchestra four years later and gave it a different concluding movement. The première of the revised version took place on April 10, 1950, with the National Symphony Orchestra of Panama conducted by Eleazar de Carvalho. The eight movements alternate tempos as follows:

- Marcha grotesca. A humorous introduction to the suite with fragmentary motives scattered among the instruments.

- Meditación. Solo cello with higher shimmering strings.

- Pasillo. This dance became popular during Columbia’s colonial period (when Panama was part of its now Southern neighbor). Descended from the European waltz, it is Africanized by the hemiola division of six into two groups of three units and three groups of two.

- Danzonete. The prominent rhythm here, strongly Afro-Caribbean, is the pattern of 3+3+2, on the claves most conspicuously, which serves as a background for brass solos and string passages.

- Nocturno. The transparent textures of this contrasting movement are set for winds and strings.

- Mejorana. The additive rhythm of the hemiola returns vividly, its articulated rhythms serving as a background to the aggressive trumpet.

- Plegaria (prayer). This highly ardent and expressive movement for strings is almost minimalist in the economy of its material, virtually unharmonized.

- Allegro Final. The suite concludes with a reminder of previously stated ideas, much in the style of the tamborito, the prime national dance of Panama, according to Cordero.

In just under a dozen minutes, Cordero successfully captures the essence of Panama’s popular musical culture and, at the same time, transforms it into something more enduring. Cordero’s accomplishment recalls William Grant Still’s “elevation” of the blues in his Afro-American Symphony, as well as earlier composers who managed to raise the musical level of popular 19th and early-20th century dances: Schubert with his waltzes and Joplin with his rags.

Dr. Cordero has enjoyed a major career as both composer and educator. He returned to Panama in 1950 and taught composition for a decade and a half. Following a stay at Indiana University, he joined the faculty of Illinois State in 1969, where he remained until his retirement in 1999.

In 1996, George Walker became the first living African American composer to win the Pulitzer Prize, awarded for his Lilacs, which received its premiere that year by soprano Faye Robinson and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Seiji Ozawa. The composer’s credentials are enormously impressive. Born in Washington, D.C. in 1922, he entered the Oberlin Conservatory at age 15 and later became one of the first African Americans to attend the Curtis Institute of Music (where he studied piano with Rudolf Serkin and Mieczyslaw Horszowski, and chamber music with Gregor Piatigorsky and William Primrose). He followed this with advanced studies in piano at the Eastman School of Music, and lessons with Robert Casadesus and Clifford Curzon. Nadia Boulanger praised his early efforts and accepted him, uncharacteristically, as a private student. Following various faculty appointments in Maryland, Massachusetts, Louisiana, and Colorado, he went on to chair the music department at Rutgers University.

Walker considered himself foremost as a pianist. He did not become widely known as a composer until Paul Freeman began to issue recordings of Walker’s orchestral music in the 1970s. Natalie Hinderas also enhanced Walker’s reputation by championing his piano works in her tours and lecture-recitals and on her recorded anthology of music by Black composers. Commissions began to arrive for new works from the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Washington Society for the Performing Arts, Baltimore Symphony, Symphony of the New World, Eastman School of Music, American Guild of Organists, and pianist Leon Bates. Performances of Walker’s music soon became frequent.

Walker wrote Lyric for Strings in 1941 as a memorial to his grandmother. He later incorporated it as the second movement of his First String Quartet (1946). Lyric opens with the instruments entering one at a time, establishing the dark warmth of its F-sharp major key. An eloquent melody weaves its way through the different string groups. After a brief interlude of cadential figures, the melody returns and builds to an intense climax. A varied restatement of the theme is again followed by cadential figures that draw this work of remarkable expressiveness and simplicity to a quiet close.

Lyric for Strings exhibits the intense romantic spirit of a composer better known as a neo-classicist. Completely tonal, and as tender and heartfelt as any work in the string orchestra repertoire, the elegiac piece is unique in the composer’s output: Dr. Walker has stated that he does not repeat a success.

Hale Smith was born in Cleveland in 1925. After completing his studies with Marcel Dick at the Cleveland Institute of Music, he moved to New York and became active as a composer. At the same time, Smith drew on his early experiences in publishing (working as an apprentice to his father) to serve as an editor for several major music publishers and as a consultant to Chico Hamilton, Isaac Hayes, Quincy Jones, Ahmad Jamal, Dizzy Gillespie, Oliver Nelson, and Horace Silver. As mid-career approached, Smith was on the faculties of both C. W. Post College and the University of Connecticut, and appeared frequently as a panelist or guest lecturer on major campuses.

Although proud of his heritage, Smith has ardently rejected any a priori racial designation. He has not wanted this to be a primary consideration for notice: it is his fervent wish that his works be evaluated purely for their merit and not featured exclusively at all-Black events. Nonetheless, Smith has stated that his compositional style does exhibit his particular relationship to his heritage:

“I am a Black composer who has extensive experience in jazz and non-jazz areas. When I write of these experiences, my way of sensing rhythm, pitch relationships, formal balances, and so on, are influenced by my background. The fact that a lot of my music would come off much better if it were played by performers with jazz backgrounds doesn’t mean that I’m writing jazz, but it does mean that it’s written by a person who had that type of experience, who thinks that way.” [CITATION TO COME]

Smith is thus a distinctly American composer.

Ritual and Incantations is dedicated to Francis Thorne, whose Thorne Music Fund commissioned the piece. Paul Freeman conducted its première during a weeklong symposium held in 1974 with the Houston Symphony Orchestra at local universities. While Smith has also been influenced by the 12-tone system, he has remained as independent of its orthodoxy as Cordero. Smith does, however, admit to using a set early in Rituals and Incantations as a source for what follows. He makes extensive use of percussion throughout this work, basing the writing on idealized African drumming. Although Smith has offered no program for the work, it is highly evocative, creating an atmosphere of mystery with decidedly sinister undercurrents.

Adolphus Cunningham Hailstork was born in Rochester, New York in 1941, but spent most of his childhood in Albany, where he joined the choir of the Episcopalian cathedral. From this experience he developed an interest in vocal melodic writing that asserts itself not only in his choral works and art songs. Directing his attention to composition, Hailstork entered Howard University in 1959, where he studied with Mark Fax and Warner Lawson. This was followed by study in France with Nadia Boulanger, at the Manhattan School of Music with David Diamond and Vittoria Giannini, and doctoral studies with H. Owen Reed at Michigan State University.

Hailstork’s first faculty appointment was at Youngstown State University in Ohio. During this time, he attended the 1975 Black Music Symposium in Minneapolis, where Paul Freeman was conducting a series of events, including a reading session devoted to new works. One of these was Hailstork’s Celebration!, a work commissioned by the J. C. Penney Foundation in anticipation of the American Bicentennial. It proved to be exceptional in all respects. Freeman chose to include it on the Minnesota Orchestra concert at the Symposium’s conclusion, and the piece has been widely performed since. Soon after this success, Hailstork joined the faculty of Norfolk State University. In 2000, he became professor of composition at Old Dominion University in the Tidewater, Virginia area, where he also serves as choral director at the Unitarian Church of Norfolk.

Hailstork’s large-scale works include two symphonies, a piano concerto, and two operas: Paul Laurence Dunbar: Common Ground (written for the Dayton Opera Company) and Joshua’s Boots (commissioned by the Opera Theatre of St. Louis). While his works have long been championed by Dr. Freeman, many have now been added to the repertoires of Daniel Barenboim, Leon Bates, Lorin Maazel, Kurt Masur, violist Amandi Hummings, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Boys Choir of Harlem and, very frequently, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra.

From the start, Hailstork has identified himself as a pragmatic composer. “Culture,” he has stated, “does not have to stop at the doors of the symphony hall” — a credo by which Hailstork has consistently lived. In 2000, for example, he came to Albany, Georgia to serve as professor at both Darton College and Albany State University, and as visiting choral director at Mt. Zion Baptist Church; he also worked with fifth-grade students. When the city’s orchestra presented a series of concerts of his works, these included performances with students from Albany’s high school choruses.

The death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. has been commemorated by many composers, not only Americans. One of the earliest such works is David Baker’s 1968 cantata, Black America, filled with many contrasting moods, but essential a cry of pain and protest. Hailstork’s 1979 Epitaph, by contrast, comes after a decade of reflection. Showing his distinctive mastery of orchestration and harmony, it is a work of transcendent beauty that conveys the nobility of its subject, and serves as a tribute of acceptance.

In his exuberant moods, Dr. Hailstork creates an infectious excitement that sometimes glosses over the very careful details of the organic construction of his music. Such is the case with both Celebration! (1974) and An American Port of Call (1985), commissioned by the Virginia Symphony. The work is in a ternary form: the initial presentation of melodic ideas is followed by a section that plays with their implications and a conclusion that serves as a reminder of the original materials.

Album Details

Total Time: 51:02

Recorded: May 10, 1995 (Tracks 3-11, 13) & January 15, 2001 (Tracks 1, 2, 12) in Lund Auditorium at Dominican University, River Forest, Illinois.

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone Cover

Photography: Martin Luther King Jr. Before a Speech © Bettman/CORBIS and Memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. © Flip Schulke/CORBIS. License granted by Intellectual Properties Management, Atlanta, Georgia, as manager of the King Estate.

Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Dominique-Rene de Lerma

* Under license from Platinum Entertainment, Inc.

©2001 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 061