| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

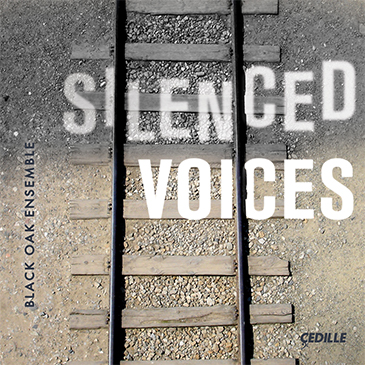

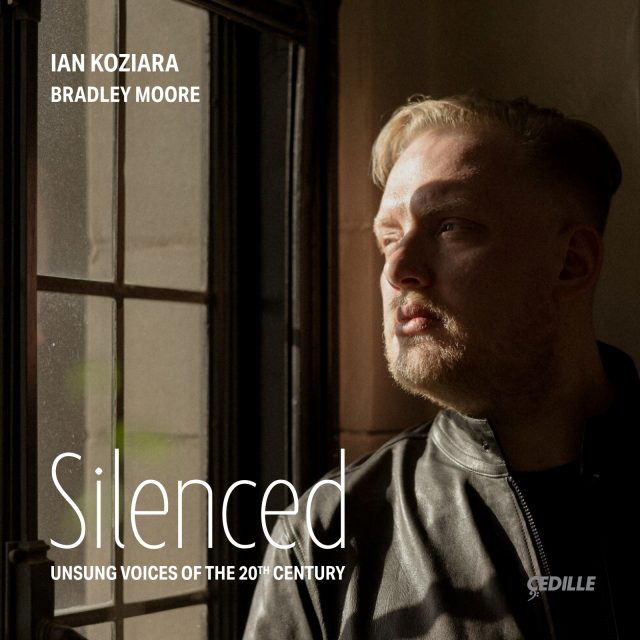

Silenced – Unsung Voices of the 20th Century

Silenced – Unsung Voices of the 20th Century, featuring tenor Ian Koziara and pianist Bradley Moore, shines a light on art songs by Franz Schreker, Vítězslava Kaprálová, Viktor Ullmann, and Alexander von Zemlinsky, whose musical achievements were overshadowed by the oppression of the Third Reich. This album marks the first tenor-voice recording for almost all of these rare songs.

Described as “an exciting Wagner tenor” (New York Times) and “a wonderful artist” (Washington Post), Chicago native Ian Koziara has performed at leading venues including the Metropolitan Opera, Carnegie Hall, Glimmerglass, Teatro La Fenice, and Opéra National du Capitole, among others. He sings regularly at Oper Frankfurt, where he recently starred in Franz Schreker’s Der ferne Klang.

Bradley Moore has served as associate Music Director at the Houston Grand Opera and assistant conductor at the Metropolitan Opera and Salzburg Festival. He has performed as a piano soloist with orchestras including the National Symphony Orchestra and Buffalo Philharmonic, and has collaborated in recital with artists such as Renée Fleming and Susan Graham.

This recording explores the operatic and chromatically rich German harmonies of early 20th-century composers Franz Schreker (1878–1934) and Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871–1942), alongside the esoteric textures of Viktor Ullmann (1898–1944), who wrote his Hölderlin-Lieder and Drei Lieder, Op. 37 during his internment at the Terezin concentration camp.

Vítězslava Káprálová (1915–1940), the least known and shortest-lived composer on the program, was a trailblazer as the first Czech woman to become a professional conductor and the first woman ever to conduct the Czech Philharmonic. Káprálová possessed extraordinary talent and technical virtuosity, and her passion for song and poetry are reflected on this program in sets such as Dvě písně, Op. 4 and Jablko s klína, Op. 10. Tragically, Káprálová’s career was cut short by her untimely death at age 25.

Click here for a playlist inspired by this album.

Silenced – Unsung Voices of the 20th Century was produced and engineered by the Grammy-winning team of James Ginsburg and Bill Maylone. It was recorded July 26–28, 2023 in the Mary Patricia Gannon Concert Hall at DePaul University, Chicago, IL.

This recording is made possible by the generous support of Patricia Kenney & Gregory O’Leary, Eva Lichtenberg & Arnold Tobin, and the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Fund for Vocal Recordings at Cedille Records.

Eva Fishell Lichtenberg and Arnold Tobin dedicate their support for this recording to the memory of her parents, Margaret and Walter Fishell. Eva and her parents were born in Liberec, Czechoslovakia, now the Czech Republic. Alone among an extensive family, they survived the Holocaust through an arduous journey to the United States (1938–1941). Presenting the music of composers who lived, worked, and/or were imprisoned in the former Czechoslovakia is a tribute to their personal histories.

Preview Excerpts

Franz Schreker

Fünf Lieder, Op. 4

Vítězslava Kaprálová:

Dvě písně, Op. 4

Viktor Ullmann

Drei Lieder Op. 37

Kaprálová

Jablko s klína, Op. 10

Alexander von Zemlinsky

Fünf Gesänge, Op. 8

Zemlinsky

Ullmann

Kaprálová

Navždy, Op. 12

Ullmann

Hölderlin-Lieder

Kaprálová

Sbohem a šáteček Op. 14

Artists

1: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

2: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

3: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

4: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

5: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

6: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

7: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

8: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

9: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

10: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

11: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

12: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

13: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

14: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

15: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

16: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

17: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

18: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

19: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

20: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

21: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

22: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

23: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

24: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

25: Ian Koziara, Bradley Moore

Program Notes

Download Album BookletProgram Notes

Notes by Roger Pines

As National Socialism emerged in 1930s Germany and grew to horrific proportions during World War II, it ravaged the lives and careers of innumerable musicians in central and eastern Europe. Among these were the four composers to whom this disc pays tribute. Their music has been dismayingly under-recorded (especially that of the least familiar figure here, Vítězslava Káprálová). They all excelled in art song, yet this repertoire is among the least-known areas of their work. Their songs reached heights of expressive eloquence, achieved through stunning musical imagination and acute textual intelligence.

Son of a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, Franz Schreker (né Schrecker, 1878–1934) had an unsettled childhood. Due to his father’s work as a photographer, he lived in five different countries before the age of five. The family wound up in Linz, Austria, where Schreker spent six years before completing his musical education at the Vienna Conservatory. As a composer, Schreker moved quickly up the ladder of public recognition. One of his earliest works, the “Ekkehard” overture (1902–1903), was premiered by the Vienna Philharmonic, no less. One of Vienna’s most active propagators of new music, Schreker premiered his first opera there: Flammen (1902). Having taught in Vienna for several years, he relocated to Berlin in 1920 to become director of the Hochschule für Musik. His tenure there exerted an incalculable influence on the next generation of central European composers.

Schreker thrived professionally throughout the 1920s, but rapidly escalating antisemitism eventually led to his resignation from the Hochschule. Although allowed to teach at Berlin’s Preußische Akademie der Künste, he was forced to leave this position in September 1933 and died of a (likely stress-induced) stroke three months later. Only after decades of neglect (starting with a ban on his music during the Third Reich) did his music gain greater notice internationally, with particular acclaim for his two magnificent operas: Der ferne Klang and Die Gezeichneten.

A Straussian gift for lyrical outpouring springs instantly to mind in many of

Schreker’s more than 40 songs, the majority of which date from the closing

years of the 19th century. Among the five glorious songs that make up Schreker’s opus 4, a special joy is “Unendliche Liebe,” with text by Tolstoy. The singer exults that the earth’s boundaries cannot restrict his love, which is as wide as the sea. Schreker confirms this declaration with a rippling accompaniment, beautifully supporting the singer’s flowing legato. Equally memorable is “Frühling,” with its captivating text by a surprising poet: legal scholar Karl Freiherr von Lemayer. A true gift for a radiant, yet full-bodied lyric voice, “Frühling” withstands comparison to any of the many memorable depictions of spring in German Lieder.

The celebrated realist poet Theodor Storm was in an extravagantly emotional mood with the text of the third song, “Wohl fühl ich wie das Leben rinnt.” Anticipating death, the singer mentions one “last” after another — the last kiss, last magical drink, last sunset, last star — that he’ll experience as his life ebbs away. Schreker continually enhances the fervency of the vocal line with the notably varied piano part, whether in slow chordal movement at the start or, in more vigorous sections later, when the singer indicates that his beloved has offered him “der Jugend letzter Gruß” (youth’s last greeting), as the pianist’s left hand launches a series of virtuosic 16th-note sextuplets.

Born in Vienna and raised Jewish, Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871–1942)

trained at his hometown’s conservatory. In his early ventures as a composer, he earned gratifying encouragement from Johannes Brahms. His own music represents perhaps the ultimate bridge between the twilight of romanticism and the introduction of the modernism exemplified, above all, by Schoenberg. A profoundly influential teacher (his students included Berg, Krása, Korngold, Weigl, and Webern), Zemlinsky also conducted superbly for the two Vienna opera companies and at Prague’s Deutsches Landestheater. He moved to Berlin in 1927 to conduct at the Kroll Opera, while also undertaking engagements with major orchestras across Europe.

With Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Zemlinsky left Germany. He led an itinerant existence until 1938, when he and his wife settled in New York, but he achieved little recognition thereafter. Today, he remains most celebrated for one of the 20th century’s greatest works for vocal soloists with orchestra, the Lyrische Symphonie (1923). In recent decades, enterprising companies worldwide have produced several Zemlinsky operas successfully, especially Der König Kandaules (1936) and two one-act works often paired as a double-bill: Eine florentinische Tragödie (1917) and Der Zwerg (1922).

In Zemlinsky’s opus 8 (1899), the tower guard of “Turmwächterlied” addresses his words to people everywhere around him, whether in castles or on the street. Urging them to look heavenward and pray, he asks the Lord to take them into His grace. A certain stirring gravitas invades the song, with its very stately vocal line — initially marked Langsam (slowly) and feierlich (solemnly) — plus its quiet introduction and heavily chordal accompaniment

For “Und hat der Tag all seine Qual,” Zemlinsky set a translated text by the

short-lived Danish writer and scientist, Jens Peter Jacobsen. The composer

aptly marked it Sehr langsam und leise (very slowly and quietly), with the singer describing the spirits of heaven who confront all the miseries of the earth that have floated skyward. As the voice flows in legato, Zemlinsky enhances it with the piano’s own separate lyrical line, integrated beautifully with the voice.

“Tod in Ähren” finds Zemlinsky masterfully setting a text by Detlev von Liliencron, one of Germany’s most outstanding lyric poets of the mid- and late-19th century. The picture here is devastating: mortally wounded, a soldier thinks of home as he lies dying in a field of corn, wheat, and poppies. The piano begins by playing heavy chords in dotted rhythms, with equally heavy octaves underneath and an angular vocal line above it. Midway into the song, as the soldier has his final dream, the voice suddenly turns quieter and offers a sweeter legato, yet one punctuated with unexpected intervals. Listen especially for the ascending leap of a ninth and descending leap of a minor sixth in the first phrase.

In “Mit Trommeln und Pfeifen,” another Liliencron text, the singer remembers marching with drummers and pipers in battle — something he can no longer do, owing to his wooden leg. Now he finds the drums’ and pipes’ noise hard to bear, but can still bring himself to cheer for the Emperor and his army. The song is marked Marschmässig (march-like), with that feeling emphasized in each bar by the repeated figure of two eighth notes and a quarter note in the piano part, a good match for the assertive vocal line.

With “Herbsten” (1895–1896), Zemlinsky chose to set a melancholy poem by Austrian writer Paul Wertheimer. In music marked Unruhig bewegt (uneasily moving), the dark mood emphasized by an F-sharp-minor tonality, tree branches moan in the wind, and all wishes that had bloomed so brightly now sink sadly into “das große, große Sterben” (death). Much of the time, the vocal line moves stepwise in a narrow range, but punctuated by

unsettling jumps to high F-sharp.

Austrian Silesia was the birthplace of Viktor Ullmann (1898–1944), whose

father — to get ahead in the military — converted from Judaism to Catholicism. Having shown obvious musical promise in high school, Ullmann entered the military himself and did well there, but eventually enrolled as a law student at the University of Vienna, concurrently studying composition under Schoenberg. Mentored by Zemlinsky in Prague, Ullmann worked as a chorus master and opera conductor there while producing a good deal of his own music including, most prominently, his Symphonic Fantasy and Concerto for Orchestra.

Over the next few years, Ullmann led performances at another Czech opera

house, in Ústi nad Labem (then Aussig); triumphed with the Geneva premiere of his Schoenberg Variations; and composed extensively for Zürich’s Schauspielhaus. Surprisingly, he then halted his musical activities for two years. During that time, in Stuttgart, he ran his own bookstore devoted to anthroposophy, the spiritual movement founded by Rudolf Steiner, a significant influence on Ullmann.

Once Hitler took power, Ullmann resettled in Prague. His most imposing work at the time was his first opera, Der Sturz des Antichrist, a work rooted in anthroposophy and a searing response against the increasingly terrifying autocracy of National Socialism.

Ullmann and his wife sent their children to Britain via the Kindertransport, but the couple was deported to the Terezin concentration camp in 1942. Miraculously, Ullmann composed more than 20 works there, including his bestknown work today, the one-act operatic parable Der Kaiser von Atlantis. He died two days after being transferred to Auschwitz in October 1944.

Ullmann composed several dozen songs. For his opus 37 (1942), he chose three texts by Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, the 19th-century Swiss poet and novelist. “Schnitterlied” celebrates the young men and women who reap corn in rain or shine. One’s ear is struck immediately by the song’s exhilarating rhythmic drive, consistently unsettled harmony, and jagged vocal line demanding maximum flexibility and accuracy. Much calmer is the second song, “Säerspruch.” Here the sowers are reminded that rest is good for the seeds (a certain ambiguity colors the harmony again, however: one doesn’t know whether the seeds will grow or not). Ullmann marked “Die Schweizer” with the adjective Wuchtig (massive), entirely suitable, given the almost unrelievedly heavy, foursquare phrasing required for this song of the Swiss guards. The song’s tonality is strikingly indeterminate throughout, with the vocal line presenting another formidable test for the singer’s intonation.

The writing of German poet-philosopher Friedrich Hölderlin has attracted composers from Beethoven and Brahms to Henze and Ligeti. Boston-based professor Jennifer Zabelsky has noted that “[Hölderlin’s] verses are Classical in syntax and form, but are seen as Romantic because of the mysticism they invoke and his use of topics related to nature.” In “Sonnenuntergang,” the first of Ullmann’s three Hölderlin-Lieder, (generally thought to date from 1943 and 1944), the singer wonders where his beloved can be, after the pleasures they’ve shared. Here Ullmann returns to lyricism, although the song covers a two-octave range within which the vocal line’s intervals are, once again, enormously challenging to negotiate. Much the same applies in the next song, “Der Frühling” — if anything, an even more exacting piece for the singer.

Lengthiest by far of the three songs is “Abendphantasie.” Here the singer feels the evening’s calm, yet his aching heart will be comforted only in death. The third verse turns agitated as he wonders whether the predictable daily alternation between work and rest will calm his heart. Otherwise the song is all legato and, yet again, exceedingly wide-ranging. Note especially the most welcome (and exquisitely beautiful) F major that enters the harmony at “Komm, sanfter Schlummer” in the last verse.

The precocious child of musical parents, Vítězslava Káprálová (1915–1940) began composing at a very young age. Eventually studying composition at the Brno and Prague conservatories, she was equally gifted as a conductor and learned from some of the best: Zdenek Chalabala and Václav Talich in Czechoslovakia and, in Paris, Charles Munch, who began teaching her in 1937.

The first Czech woman to become a professional conductor, Kaprálová was also the first woman to lead a performance with the Czech Philharmonic, with which she conducted her own Military Sinfonietta. That work also graced her debut with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1938. Among Kaprálová’s other major works are two piano concertos, a large-scale cantata, diverse choral and chamber music, and works for solo piano. When her scholarship to work in France was revoked by the Nazis, she chose to stay nevertheless, composing with almost maniacal intensity before succumbing to typhoid fever (or, in some accounts, possibly tuberculosis) in Montpellier at age 25.

The poetry for Kaprálová’s opus 4 is by a writer known pseudonymously as

“R. Bojko.” In “Jitro,” the first of the two opus 4 songs, the 17-year-old Kaprálová already displays an astonishing instinct for vocal writing. Setting a text that depicts a lovely morning scene, she gives the singer moments of near-Straussian expansiveness. A great contrast can be heard in the melancholy Kaprálová achieves with the text of the second song, “Osiřely.” There are highly distinctive images in this poem, such as when the lover, longing for his beloved, observes that “silvery arms of white rivers” were

rising “for a kiss from the stars.”

For opus 10, Kaprálová set texts of Jaroslav Seifert, the 20th century’s best-loved Czech poet, who expressed vehement public opposition to the Nazis and, later, the Communists (In 1984, he became the first Czech to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature). These poems’ sentiments are instantly accessible, and not at all grand-scale. In the first song, there’s the hope that God will care for even the world’s littlest creatures. Then comes a lullaby, in which the singer tells the child to go to sleep and not think about his absent father. The third song finds the singer dreaming in the streets of Nineveh. Then comes the delightful last song, instantly communicating the appeal of a spring fair. Kaprálová’s music illuminates each text, particularly in the lulling of eighth notes supporting the floating vocal line of the second song. Also notable are the somber, almost eerie, aura of mystery pervading No. 3 and the scintillating piano part in No. 4, perfectly evoking the fair’s giddy atmosphere.

For the first two songs of her opus 12, Kaprálová turned to poetry by another compatriot, Jan Čarek. In the first song, the composer gracefully evokes the image of south-flying geese overhead. Considerable intensity colors the second song, as the singer asks, “What is my grief against your seas, what is my pain against the sand of your deserts?” Kaprálová turned again to Seifert for the last song; here the lover’s increasingly passionate phrases rise to a spectacular climax on a series of high As at the conclusion. The singer’s smooth legato is excitingly supported by the piano’s coruscating quintuplets and sextuplets.

In the language of another distinguished Czech poet from the first half of the 20th century, Vítězslav Nezval, Kaprálová found her text for “Waving Farewell” (opus 14). The lover imagines what might follow his final goodbye to his beloved, concluding that if they are indeed meant to see each other again, they should at this moment say nothing, and instead, simply wave. Sweetness and tenderness turn to passion, only to have a return to calm in the song’s final pages. One hears all the expressive variety and technical virtuosity (not just in the voice but also in the piano part) that will cause listeners genuine grief that Kaprálová’s gifts had so little time to flower.

One can’t help feeling overwhelmed by sadness when listening to this recital. And yet, at the same time, these four courageous, sublimely gifted composers all remind us that we must continue to express our outrage whenever we see artistic freedom compromised — or even destroyed altogether — by any authoritarian regime. We’re fortunate indeed that, with their performances here, Ian Koziara and Bradley Moore can introduce this extraordinary music to new audiences, inspiring in them a thrilling sense of discovery.

Roger Pines has contributed program notes to eight major recording companies, among them Decca, Sony Classical, Deutsche Grammophon, and Erato. His feature articles and reviews have appeared in Opera News,

Opera magazine (U.K.), Das Opernglas (Germany), and many opera-company programs. He has been a faculty member in the voice and opera department of Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music since 2019.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Steinway Piano Technician Richard Beebe

Recorded

July 26–28, 2023, Mary Patricia Gannon Concert Hall, DePaul University, Chicago, IL

Publishers

Kaprálová : Dvě písně, Op. 4 © 2005 Amos Editio

Ullmann: Drei Lieder, Op. 37 © 2005 Schott Music

Kaprálová: Jablko s klína, Op. 10 © 2005 Amos Editio

Zemlinsky: Herbsten © 1995 G. Ricordi & Co.

Ullmann: Schwer ist’s, das Schöne zu lassen © 2004 Schott Music

Kaprálová: Navždy, Op. 12 © 2005 Amos Editio

Ullmann: Hölderlin-Lieder © 2005 Schott Music

Kaprálová: Sbohem a šáteček, Op. 14 © 2005 Amos Editio

Cover Photo Jaclyn Simpson

Graphic Design Bark Design

CDR 90000 231