| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

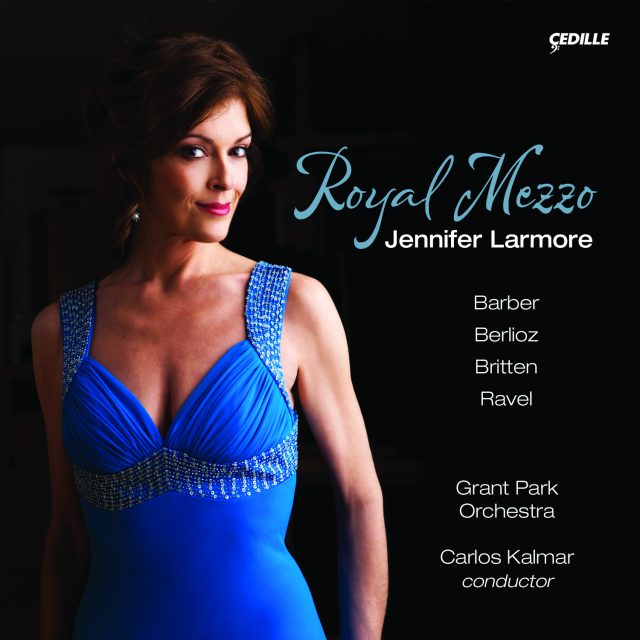

World-renowned mezzo-soprano Jennifer Larmore sings four royal roles in a tour de force program of dramatic orchestral works.

Surging with epic emotions, Royal Mezzo showcases Ms. Larmore in symphonic portraits of commanding characters from legend, literature, and mythology.

Samuel Barber’s haunting Andromache’s Farewell depicts the anguish of a Trojan queen forced to give up her son after the Greeks conquered her city. The bold harmonies and orchestral colors of Hector Berlioz’s La mort de Cléopâtre (The Death of Cleopatra) shocked the French musical establishment. Maurice Ravel’s dreamy and sensuous song cycle Shéhérazade was inspired by the storytelling queen of The Arabian Nights. And Benjamin Britten’s graphic Phaedra recounts a mythic tale of lust and guilt in ancient Athens.

Jennifer Larmore delivers it all with her trademark dramatic intensity and “faultless technique” (BBC Music), matched by the “exuberance, commitment and edge” (The New York Times) of the Grant Park Orchestra under Carlos Kalmar. </p

Preview Excerpts

SAMUEL BARBER (1910–1981)

HECTOR BERLIOZ (1803 - 1869)

La mort de Cleopatre

MAURICE RAVEL (1875 - 1937)

Sheherazade

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976)

Artists

7: Mary Stolper, solo flute

Program Notes

Download Album BookletRoyal Mezzo

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The word “Cantata” had two meanings in the Baroque era. One is represented by Bach’s compositions for Lutheran church services in Leipzig: works for soloists, chorus, and small orchestra that both reproduced and commented upon texts from the Bible in a succession of recitatives, arias, and chorales. The secular cantatas of Handel and Alessandro Scarlatti (and numerous lesser-known contemporaries) are quite different. Usually scored for one singer — sometimes two — with accompaniment from perhaps five or six instrumentalists, these short and vivid dramas depict stories from classical mythology or poems about rejected and despairing lovers. Recitative portions laying out the plots are alternated with arias expressing the character’s feelings. These cantatas were an alternative to opera for aristocratic audiences who would otherwise be deprived of theatrical entertainment during seasons (such as Lent) when edicts from church and crown kept opera houses dark.

The generation that followed Bach and Handel kept up the tradition of the secular cantata but called it by different names. It might be called a “scena” (scene) or a concert aria. (Mozart produced quite a few concert arias.) The intention remained the same whatever the terminology: to create a miniature music drama.

A slightly different but parallel development arose in vocal music during the early 19th century. The purpose of the song-cycle was less dramatic than narrative: Schubert’s “Die schöne Müllerin” (The Beautiful Miller-Maid), for example, which tells a continuous story and sets a prevailing mood, rather than displaying a colorful emotional moment — more tapestry than portrait. Song-cycles often accompany the voice just with piano, though some, like Berlioz’s “Nuits d’Été” and Richard Strauss’s “Four Last Songs,” are scored with orchestra. Maurice Ravel followed this route in “Shéhérazade.”

History, myth, and legend have transmitted memorable images of extraordinary individuals trapped in crises. Playwrights and composers have portrayed these figures again and again to re-interpret and re-illuminate the emotions that drive them — passion, grief, guilt, revenge — and to remind us of the vulnerable mortality all humans share. Royal Mezzo brings together three portraits from ancient times cast in widely divergent musical languages and poetic styles. All three are descended from the tradition of the solo cantata and the quasi-operatic scena.

In contrast to these dramatic vignettes is Ravel’s song-cycle, a diffuse sequence of songs drawn out of the world of dreams: no less colorful than the scenas, but inspired by a poetic imagination that longed for exotic escape from reality, rather than seeking a dynamic confrontation with reality as seen across centuries and millennia.

Though he called his cycle “Shéhérazade,” Ravel didn’t choose his texts from The Arabian Nights. Those tales, famously told by Queen Scheherazade to hold her husband’s fascinated attention through 1001 nights — and thus distract him from his original plan, which was to kill her — drew Ravel at one point to contemplate a full-scale opera. (The only survival of that project is a “fairy overture” also called “Shéhérazade.”) Meanwhile, the French poet Arthur LeClère, who preferred to call himself Tristan Klingsor (apparently he liked Wagner), was creating an evocative volume of Asian-inspired verse, for which he also borrowed the name “Shéhérazade.” Three poems from this collection make up Ravel’s 1903 cycle.

Fast-forward 60 years to 1962–63, the New York Philharmonic’s first season in its new home at Lincoln Center. The Philharmonic commissioned a new work for soprano and orchestra from Samuel Barber, a composer who was himself a singer and whose previous vocal achievements included atmospheric settings of both prose and poetry: “Dover Beach” (Matthew Arnold), “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” (James Agee), and “Hermit Songs” (anonymous medieval verses). For the commission, Barber delved into the remote past of ancient Greece. Often described as “neo-Romantic,” admired for his lyrical gifts but sometimes dismissed as old-fashioned, Barber employed a decidedly contemporary musical language for “Andromache’s Farewell,” focusing on the fury in the text as much as on the grief and pathos: several orchestral passages are marked to be played “with hatred.”

The Trojan War has ended. The Greeks have killed the city’s warriors and captured their widows and orphans. Euripides’s tragedy The Trojan Women explores the fates and emotions of these survivors, who face no future to speak of. The women are being parceled out among the victors… the children, what of them? Andromache is the widow of Hector, the Trojan hero who fought hardest and bravest against the Greeks. She will be allotted as “slave-wife” (in the words of the preface to Barber’s score) to the son of Achilles, the man who killed Hector. Not content with just this revenge, the Greeks have decided that Andromache and Hector’s son, Astyanax, must be thrown over the ramparts of Troy. A hero’s son cannot be allowed to live; that he’s a little boy, still clinging to his mother’s skirts, means nothing.

John Patrick Creagh translated Andromache’s words from Euripides especially for this composition, which opens with a powerful motive on trombone and tuba that recurs throughout the scena. Flutes and violins screech a contrasting motive of grief and despair. The orchestral introduction continues to build in intensity, punctuated by a large percussion battery. The sizeable orchestra often plays as a unified ensemble, but there are also numerous solo passages that add individual voices to the chorus of despair. A clarinet solo lends its motive to the singer’s first entrance: “So you must die, my son.”

Both voice and instruments perform melodic patterns that emphasize dissonance and agitation: intervals of minor seconds, minor thirds, diminished fifths, sevenths, and ninths abound. The vocal line especially features wide leaps. There’s a dramatic descent on the words “Falling, falling, thus will your life end.” At several points the singer portrays emotion not fortissimo but pianissimo: soft high notes give special meaning to the phrases “Was it for nothing that I nursed you” and “Come close, embrace me.”

The climax of rage comes in the Allegro molto section that forms an intense coda to the work. Here Andromache turns her wrath upon Helen, whose abduction from Greece by Hector’s brother Paris unleashed the 10-year Trojan War. Andromache curses Helen’s fateful beauty, then gives up her son and allows herself to be led away. A powerful instrumental interlude leads to her final words: “Hide my head in shame? across the grave of my own son I come.”

The earliest of our compositions is the 1829 lyric scene called variously “Cleopatra” or “The Death of Cleopatra,” which the young Hector Berlioz wrote as part of his ongoing quest to win the Prix de Rome. This prestigious honor was awarded to aspiring French composers by Paris’s Académie des Beaux Arts and provided a stipend for study in Rome. The catch was that to win the prize you had to follow the academy’s rather conservative rules of musical construction and style using a pre-selected cantata text. Berlioz (never too big on following rules) eventually did win the prize, although not for “Cleopatra,” which was considered too dramatic and perhaps too new-sounding; the composer allowed his romantic imagination free rein in this highly-charged tale from the days of the Roman Empire. Hearing it today, especially on this CD, where it comes after Barber’s dissonant work, “Cleopatra” seems decidedly “classical” in its harmonic language. But Berlioz’s flair for the dramatic and his brilliant, colorful orchestration are readily apparent, even in this piece from his days of artistic apprenticeship.

Without aspiring to the level of great poetry, the text by P.A. Vieillard fully serves Berlioz’s purpose of setting up a dramatic situation to exploit musically. The story of Egypt’s glamorous queen is familiar to us from sources as varied as Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Richard Burton, and Elizabeth Taylor. Having loved and captivated both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, Cleopatra has lost them both, one killed in a political assassination, the other in battle with Octavian. She has discovered that Octavian is not susceptible to her charms: “the daughter of the Ptolemies has suffered the insult of refusal.” Exacerbating her feelings of shame and guilt is her realization that it is partly her fault that her homeland has been conquered by the Romans.

The short orchestral introduction, a mini-overture, presents a vigorous, agitated string theme punctuated with a couple of measures of rhythmic syncopation leading to a fortissimo chord for the whole orchestra and an ominous low-clarinet theme that brings us to the soloist’s first recitative: “So, then, my shame is complete.” Cleopatra reflects upon her unsuccessful attempts to sway Octavian. As in operatic recitative, the singer must get through quite a lot of words quickly to set out the story. The light accompaniment is mostly for strings alone. The first aria, marked Lento Cantabile, settles the full orchestra into the key of E-Flat Major to offer a beautiful introductory melody, but syncopated accents reveal that all is not peaceful. The aria recalls Cleopatra’s days of triumph: “Tormenting memory of days gone by, when I shared the glory of Caesar and Antony, beautiful as Venus.” The midsection finds the cruel recent memory of Octavian intruding upon her happier thoughts of the past. A slightly varied reprise brings the aria to a close.

The second recitative, accompanied by strings alone, is shorter but no less agitated than the opening: “Au comble des revers… “. Cleopatra acknowledges the harm she has done not only to herself but also to her country; she accuses herself of tarnishing the heritage of Egypt’s past glories and dishonoring the proud line of Pharaohs. It is to these dead Pharaohs that she speaks in her second aria, subtitled Meditation and introduced by a slowly-evolving chromatic theme in the lower winds and brasses, with syncopated pizzicatos in the strings. The key is F Minor; the tempo is Largo misterioso. In the score, the Shakespeare-loving Berlioz inserted a line from Romeo and Juliet: “How if, when I am laid into the tomb… “. Cleopatra asks in the aria’s first phrase: “Mighty Pharaohs, noble Lagides, will you, without wrath watch her enter, to rest in your pyramids, a queen unworthy of you?” “No!” she emphatically concludes in a faster section marked Allegro assai agitato: she would shame them by her presence, and their ghosts would rise up against her. She repeats these sentiments several times, and the orchestral sound, as if reflecting the Pharaohs’ anger, grows steadily in intensity. The mode shifts from minor to major as Cleopatra’s frenzy of guilt increases. The mood and instrumentation of the Meditation’s opening are briefly recalled, but Cleopatra has arrived at her answer: she cannot continue to live with her dishonor, she must die. The disjointed vocal motives of the coda reveal her decision: “In the face of the horror which hems me in, a vile reptile is my resort.” Leading up to this fateful decision we hear a long descending chromatic line in the strings, almost an instrumental scream. Thereafter, the orchestra somewhat effaces itself to give prominence to the words of the dying queen. With her last breath she invokes Caesar. The violins and violas, beginning pianissimo, play ostinato two-note patterns that suggest the beating of the queen’s heart. These become louder and faster, then die away on a slow diminuendo as the tempo slows from Allegro to Adagio. A rumbling final phrase for all of the strings swells briefly, then diminishes and dies away very softly. She is dead.

Berlioz’s Cleopatra has suffered through the kind of remorse and anguish philosophers have described as “the dark night of the soul.” Her resolution was self-destruction. Barber’s Andromache protested and lamented her fate and moved on to a kind of living death: sent into exile, bereft of husband and son. The world of “Shéhérazade” has no such hard edges of reality. It is a kind of extended daydream, with three allusive and evocative poems that are set in no particular place or time, relevant only to the workings of poetic and musical imagination. Ravel’s orchestra enhances the other-worldly exoticism with its emphasis on tone color: we hear the mellow, haunting sound of the English horn as often as that of its brighter cousin, the oboe, and harp glissandi shimmer around the singer’s words. The varied percussion battery includes cymbals of different sizes, a Basque drum, and the bell-like celesta. The first song, by far the longest, is like an extended recitative; voice and instruments present evanescent motives instead of shaped melodies. We’re being taken on an extended armchair tour of a highly fictionalized Asia by an anonymous narrator who admits he’s fantasizing: “Asia, Asia, Asia, marvelous old land of nursery tales.” Muted strings and a floating oboe theme launch these words almost in a whisper. As we continue our journey, we hear hints of themes that employ the whole-tone scale, an “Oriental” color-effect that charmed both Ravel and Debussy. The singer, meanwhile, comments on some delightfully strange sights: a sailing ship that departs by night, islands of flowers, the minarets of the Middle East, merchants clad in rich velvet and long fringed coats. Woodwinds and harps swirl and swoop as scenes quickly succeed one another. The tempo slows down a bit, but picks up again after we have passed Persia and India to reach the high point of the narrator’s anticipation: China. The orchestra puts a fortissimo exclamation point on this word, then immediately subsides to pianissimo.

In “China” we are shown both dark and light, painted landscapes and beautiful princesses, but also swords, “paupers and queens, . . . roses and blood.” Tempo contrasts are frequent in this China narrative. A climax is reached as the singer exclaims, “People dying of love or [even better] of hate.” The orchestra brings us back from this symbolic brink of death with a powerful tutti interlude that anticipates the Sunrise passage in Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe ballet. This subsides into another muted passage as the singer looks forward to returning home and spellbinding her listeners with tales of her great adventure. And yet she has never left home. The quiet ending — flutes, percussion, and strings — seems to say, “Only a dream after all.”

“La flute enchantée,” the second and most familiar of the songs, opens with the first real tune of the cycle, played on the flute, recurring as a main theme. The slow, soft opening evokes an elderly man asleep. But his young servant is still awake, and as the pace quickens and brightens, she tells us the flute music is being played by her lover outside the window. The entire orchestra picks up a broadened version of the flute theme as the singer muses on the melody and on love. But there will be no rendezvous tonight: the only kisses are from the haunting notes of the flute, whose theme has the last word, pianissimo.

“L’indifferent” is the most dreamlike and elusive of the three songs. Over undulating, repeated string figurations, flute and clarinet offer a wandering theme.

The singer’s opening theme, contemplative and rhythmically free, sets a mood of distant observation as she views a handsome youth with an almost girlish figure passing by the window. The singer wishes to invite him in, but the stranger passes by, oblivious. Woodwind figures, sometimes solo, muse as if from a distance. The pace remains slow, the tone almost muffled: another dream, its unreality heightened by the implication of gender ambiguity.

Almost single-handedly, Benjamin Britten revived the tradition of British opera in the 20th century. Not long after World War II, Peter Grimes was premiered in London to enormous acclaim. The title character was portrayed by Britten’s life partner, tenor Peter Pears, who also created Captain Vere in Billy Budd and Aschenbach in Death in Venice. The long Britten-Pears collaboration is so well known that we tend to forget the composer’s close artistic associations with other performers, including cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and mezzo-soprano Janet Baker. One of his last major works was for Baker: the cantata “Phaedra,” which can be heard as a one-character miniature opera. Britten, however, conceived of it as a cantata in the tradition of Handel: a composer of whose works Baker had been a distinguished interpreter. The Baroque connection in “Phaedra” is emphasized by the use of a harpsichord-and-cello continuo part; the orchestra consists only of strings and percussion.

For his text, Britten selected passages from Robert Lowell’s English translation of the 17th-century French tragedian Jean Racine’s Phèdre. Like “Andromache’s Farewell,” it takes us back to Greek mythology, in this case to one of its most tortured figures: a woman who descends from obsession to sin, thence to madness and suicide. Like so many of Britten’s protagonists, including Peter Grimes and Billy Budd, Phaedra is a tormented outsider in the society that surrounds her. In the mythological story, she is literally an outsider: a princess of the vanquished royal family of Crete, whom the conquering hero Theseus marries and brings to his kingdom of Athens. Theseus had earlier loved and abandoned Phaedra’s sister, Ariadne. His subsequent relationship with Hippolyta, queen of the warrior Amazons, produced a son, Hippolytus, now grown into a heroic, almost godlike young man. Phaedra, now queen of Athens and Hippolytus’s stepmother, cannot keep her eyes or mind off him. One part of her is horrified at this impulse toward a love at best adulterous and at worst incestuous, yet she cannot help herself. Her obsession isolates her completely, making her fearful, scheming, secretive.

Racine’s five-act drama lays out the fateful tale as it came down from ancient times. Her advances to Hippolytus rejected, Phaedra is urged by her servant and companion, Oenone, to accuse the boy of rape. Theseus believes the charge and orders his son exiled. Hippolytus is killed by a sea monster, Oenone commits suicide, and Phaedra is forced to reveal her role in the tragedy. She confesses her crimes to Theseus after taking poison.

To reduce this long progression of sin and betrayal to a coherent and brief narrative, Britten selected passages from various scenes of the Lowell translation to condense the story into a vivid vignette of horror. The percussive sounds of harpsichord, tympani, and cymbal emphasize Phaedra’s frenzy, guilt, and eventual insanity. An important motive of wide descending intervals is presented by the violins in the opening measures. Then we hear the first of many passionate, unmelodic vocal lines leaping and quivering on Phaedra’s first words: “In May, in brilliant Athens, on my marriage day, I turned aside for shelter from the smile of Theseus. Death was frowning in an aisle — Hippolytus! I saw his face turned white!” The instrumental accompaniment is spare as Phaedra acknowledges her guilty love and recalls that the goddess of love, Aphrodite, had been an enemy of her mother; is the goddess taking more revenge? And if so, against whom? For Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Theseus can all be regarded as victims.

This opening prologue and recitative are followed by a Presto aria in which Phaedra directly addresses Hippolytus. Intense, agitated strings reinforce the passion of her outpouring, which reaches a climax on the words “I love you!” She recounts how she pretended to hate Hippolytus so Theseus would not guess the truth, but “I ached for you no less.”

An instrumental interlude begins with soft string motives succeeded by ominous tappings from tympani and percussion. Another recitative begins, supported by the harpsichord-cello continuo, harking back to Baroque tradition. Now Phaedra is addressing Oenone. How is she to face her husband, knowing how she feels, fearful that Hippolytus will accuse her? A striking forte harpsichord figure emphasizes her desire to die: “Death to the unhappy’s no catastrophe.”

The final Adagio is introduced by a string passage that begins low and mounts to the upper registers via slow half steps and whole steps in a slow metrical pattern. The ominous effect is both shattered and enhanced by the rapid descending figure that leads to Phaedra’s final speech to Theseus: “My time’s too short, your highness…”. Rapid string figurations comment on Phaedra’s last words, with which she absolves Hippolytus and then takes blame for the whole tragedy. The instrumental texture once again becomes slow-moving and soft as the queen reveals she has taken “Medea’s poison” (a reference to the sorceress who appears mainly in the story of Jason and the Argonauts but who also played a part in the story of the ruling house of Athens). Soft strings and occasional percussion support the voice as Phaedra experiences “a cold composure I have never known” and waits for her eyes to “give up the light.” She declares, “I stand alone” — as indeed she has since the start of the drama. She is now doubly isolated in death, as she sees the day her eyes have “soiled resume its purity.” The opening motive returns via solo violin and leads to an ending soft to the point of near-inaudibility.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT, Chicago’s classical experience

Album Details

Total Time: 67:15

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineers: Bill Maylone, Chris Willis (Barber and Berlioz); Eric Arunas, Bill Maylone (Ravel and Britten)

Digital Editing: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover Photo: McArthur Photography (www.mcarthurphotography.com)

Recorded: in concert in Orchestra Hall, Chicago, August 4 & 5, 2006 (Barber and Berlioz) and at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance in Millenium Park, Chicago, June 29 & 30, 2007 (Ravel and Britten)

© 2008 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 104