| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

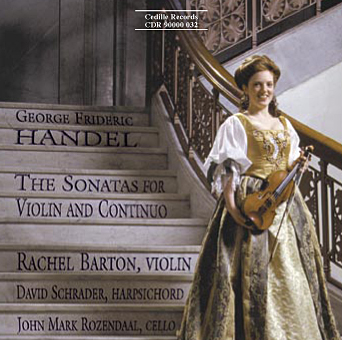

Handel’s violin sonatas, familiar to violinists and chamber audiences, have been inexplicably neglected on disc. These intimate, inviting sonatas show the seldom-heard side of Handel’s genius.

The violin sonatas span Handel’s long career, from the early, Corelli-inspired G Major Sonata, HWV358 (c. 1706-8) to the exciting Sonata in D major (c. 1750). On the CD, the works are sequenced for a pleasing progression of key relationships and mood changes.

The CD opens and closes with sonatas that are authentically Handel’s and written expressly for violin: the Sonata in A Major (HWV371), notable for its virtuosic treatment of violin and continuo parts and its noble melodic lines. Handel’s last violin sonata, it’s widely considered his masterpiece in the genre.

Scholars agree that some sonatas were erroneously attributed to Handel. Three of these are included in the program (HWV368, 370, and 372). “Regardless of authorship, they are very beautiful and well worth playing and hearing,” cellist Rozendaal writes in the CD booklet. Another, the Sonata in E major (HWV373) is excluded, “not because of its questionable authorship but because of its inferior quality,” he adds.

The program also includes several fine (and authentic) pieces from the 1724-26 period: the Sonatas in d-minor (HWV359a) and g-minor (HWV364a), the a-minor Andante (HWV412) and the c-minor Allegro (HWV408)

These performances are “historically informed,” employing a combination of 18th-century and modern practices and equipment. Ms. Barton Pine plays a 1617 Amati violin, in “modern” condition with steel strings. Mr. Rozendaal plays a 1740 cello in restored Baroque condition with gut strings. The bows used are reproductions of 18th-century models. Mr. Schrader plays a 1983 US-built harpsichord based on one in the museum of the Conservatoire National de Paris.

Preview Excerpts

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685-1759)

Sonata in A Major, HWV361

Sonata in D minor, HWV359a

Sonata in F Major, HWV370

Sonata in G Major, HWV358

Sonata in G minor, HWV364a

Sonata in A Major, HWV372

Sonata in G minor, HWV368

Sonata in D Major, HWV371

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletHandel: The Sonatas for Violin and Continuo

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

Handel’s solo sonatas for violin, oboe, flute and recorder are less celebrated works of a major master composer. Yet their beauty has earned for them a cherished place in the repertoire of instrumentalists as works both satisfying to play and effective for audiences.

Handel’s surviving violin sonatas span his entire career, beginning with the brilliant HWV358 in G major (c. 1706-08), and ending with the great D-Major sonata of c. 1750, HWV371. Unfortunately, nothing is known of the occasions for which these works were created or their first performances. However, careful study of the autograph manuscripts has allowed scholars to establish dates of composition with some accuracy.

HWV358 survives in a manuscript that dates from Handel’s brief Hanover residence (1710). Its style suggests it was composed previously, however, possibly early in Handel’s Italian sojourn (1706-09). While in Rome, Handel received the support of the Arcadian Academy, a group of the most prestigious patrons of the arts in the eternal city. His work in the palaces of Prince Ruspoli, Cardinal Pamphili, and Cardinal Ottoboni brought him into collaboration with Arcangelo Corelli, the most influential violinist of the time. Corelli’s impassioned playing and refined Apollonian style of composition became the ideal for violinists throughout the eighteenth century. Personal contact with this paragon clearly influenced Handel’s concept of writing for the violin. Corelli participated in the first performances of some of Handel’s works; he was concertmaster for the famous 1708 production of Handel’s oratorio La Resurrezione. It is tempting to imagine that Handel composed HWV358 for Corelli, perhaps as an offering at one of the meetings of the Arcadian Academy. The theatrical brilliance of the piece suggests an ear-opening prelude to a sumptuous cantata or serenata. Yet the style of this early sonata – virtuosic fast movements connected by a brief linking Largo – suggests that Handel had not completely absorbed the more lyrical Corellian approach to the violin and the sonata genre.

Corelli’s influence is more clearly heard in the beautiful sonatas of 1724-26, with their extended cantabile slow movements. These sonatas all conform to the sonata da chiesa (church sonata) layout typified in the second part of Corelli’s Opus V. Each sonata consists of four movements arranged in a slow-fast-slow-fast order, with the fast movements most often in canzona style (fugue-like, with imitative entries), only occasionally in the form of a dance movement. A number of these works (including HWV371) were published c. 1730 by John Walsh in a collection entitled Twelve Sonatas or Solo’s for the German Flute, Hautboy and Violin, and sometimes referred to as “Opus I” (six of these were for violin). Walsh’s earliest publications of Handel’s music were not authorized, and much confusion has been caused by Walsh’s unscrupulous methods. In an effort to conceal his involvement in this pirated edition, Walsh’s first printing of the collection carried a fraudulent title page indicating that it was published by the Amsterdam printer Etienne Roger in 1724. The collection also includes a number of sonatas which are almost certainly not by Handel. We have included three of these in our program (HWV368, 370, 372). Regardless of authorship, they are very beautiful, well worth playing and hearing. The sonata in E-major, HWV373 is excluded from our program, however, not because of its questionable authorship, but because of its inferior quality.

Special mention should be made of several fine pieces from the 1724-26 period that do not appear in their original form in the Walsh publication (the sonatas are in Walsh but transcribed for different instruments): the sonatas in d-minor (HWV359a) and g-minor (HWV364a), the a-minor Andante (HWV412) and the c-minor Allegro (HWV408). These relatively little-known works, all surviving in autograph manuscripts in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, (and therefore securely attributed to Handel) have much to recommend them. Note the lively Italianate dialogues between the violin and the bass line in the second movements of both sonatas; the broad lyricism of the Andante; and the Beethovenian drive of the c-minor Allegro.

Handel returned to the violin sonata one last time, around 1750, to compose his masterpiece in the genre: the Sonata in D-Major (HWV371). This exciting piece, unpublished in the composer’s lifetime, surpasses its siblings in its virtuosic treatment of both parts and the nobility of its melodic lines. Handel thought so highly of this work that he reused its last movement in the oratorio Jephtha to give special brilliance to the appearance of the angel.

The performers on this recording have attempted to create historically informed performances using a combination of 18th-century and modern practices and equipment. Ms. Barton’s violin was made in 1617 by Nicolo Amati (see note below); it is in “modern” condition, strung with steel strings. The cello is the work of the Roman maker Jacobus Horil from circa 1740, in restored baroque condition with gut strings. The bows used are modern reproductions of early 18th-century models. The double-manual harpsichord used in this recording was built in 1983 by Lawrence G. Eckstein of West Lafayette, Indiana. It is based on the Dumont-Taskin harpsichord which is kept in the museum of the Conservatoire National de Paris. It has two sets of unison-pitched strings and one set tuned an octave higher. Extensive work on the instrument’s action was carried out by Paul Y. Irvin. The pitch used in this recording is the modern standard of A=440.

Given this mixed approach, the listener may ask whether this is an “authentic” rendition or a “modern” one. In fact, our performances are probably more conditioned by our particular temperaments, attitudes, and training (including performance practice study) than by any of the conditions noted above. The truth is, we strive, as all artists should, to reveal beauty in the music by whatever means seem best; and that is the most important authenticity.

About the Violin

Rachel Barton plays the “ex-Lobkowicz” Antonius & Hieronymous Amati of Cremona, 1617, on generous loan from her patron.

The Seal of the Lobkowicz Family on the back of the violin identifies it as one of the instruments held by this illustrious European family. Prince Lobkowicz was a significant patron of Beethoven.

The Amati family is responsible for the violin as we know it today. Andreas Amati invented the violin c. 1550. His sons Antonius and Hieronymous, known as the Brothers Amati, brought violin making forward into the 17th century. Hieronymous’s son Nicolo continued to nearly the end of the 17th century and was the teacher of Andreas Guarneri and Antonio Stradivari.

The violin Miss Barton plays is a particularly fine example of the makers’ work and is excellently preserved. The top is formed from two pieces of spruce showing fine grain broadening toward the flanks. The back is formed from two pieces of semi-slab cut maple with narrow curl ascending slightly from left to right. The ribs and the original scroll are of similar stock. The varnish is golden-brown in color.

Album Details

Total Time: 68:07

Recorded: December 3-5, 1996 at WFMT, Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Photography by Cheri Eisenberg & Dan Rest

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: John Mark Rozendaal

© 1997 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 032