Store

Store

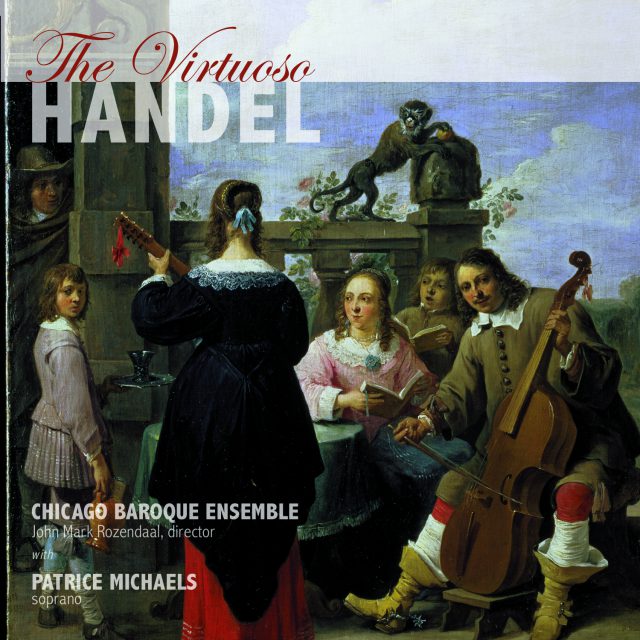

The Virtuoso Handel

Chicago Baroque Ensemble, Patrice Michaels

John Mark Rozendaal, David Schrader

Experience a side of Handel that’s rarely heard these days: exquisitely refined vocal and instrumental chamber music, including three cantatas from his early years in Italy. On The Virtuoso Handel, you’ll encounter the type of intimate music making that small, privileged audiences of discerning connoisseurs enjoyed during Handel’s sojourn in Rome from 1706 to 1709.

Italy at the start of the 18th century was obsessed with singing. It is in this vocally-infused spirit that The Virtuoso Handel was conceived.

The Chicago Baroque Ensemble and soprano Patrice Michaels previously collaborated on Cedille’s acclaimed A Vivaldi Concert (“A stellar level of artistry.” – Cleveland Plain Dealer) and The World of Lully (“All this virtuosity invites repeated listening.” – Early Music America). Here they perform secular cantatas on themes of romantic love, history, and mythology, including the dramatic and harrowing La Lucrezia. These challenging pieces showcase Ms. Michaels’ silvery voice, lively interpretations, and exceptional mastery of florid Baroque passagework and ornamentation.

Also included are instrumental arrangements of arias from three of Handel’s Italian operas: two for flute and strings, with irresistible “coloratura” playing on the transverse flute, and one for solo harpsichord. Completing the program is a charming Sonata in C Major for viola da gamba and harpsichord, which casts both players in virtuoso roles.

Participating on this recording are Chicago Baroque Ensemble members Anita Miller-Rieder, transverse flute; Jeri-Lou Zike, violin; Susan Rozendaal, viola; John Mark Rozendaal, viola da gamba and cello; and David Schrader, harpsichord.

Preview Excerpts

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685-1759)

Cantata: Un alma innamorata

from "Floriodante" transcribed for harpsichord solo

Cantata: Chi rapi la pace al core?

Sonata in C for viola da gamba & harpsichord

Artists

1: transcribed for flute and strings

25: transcribed for flute and strings

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Virtuoso Handel

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

Both in his own time and after his death, Handel’s high reputation as a composer has rested mainly on the grandly stirring gestures of his most public works: the operas and oratorios he composed for the theaters of Georgian London. Yet Handel’s œuvre includes a substantial body of chamber music, including some of the most satisfying and beautiful secular music of the period. The works selected for this disc come from a variety of sources; they include works created as vocal chamber music as well as operatic excerpts adapted for small-scale instrumental presentation.

The earliest works on our program are the three cantatas, all dating from Handel’s Italian sojourn of 1706 –1709. During his stay in Italy, Handel produced at least for ty solo cantatas, most of them scored for soprano and continuo — a body of work that represents the zenith of an important genre in Italian music. Between 1650 and the end of the Baroque era, Italian composers wrote dozens of such works to fill an apparently insatiable demand. Alessandro Scarlatti composed over 600. Marc’ Antonio Cesti satirized the craze in a mock cantata titled “Aspetate, addesso canto!” (“Wait! I’m Singing Now!”):

Everyone is looking for texts, all women want them . . . Ladies, nuns, old maids, wives, widows, female relations, public women, private ones, princesses, damsels; I don’t say which ones; enough only that so, so many want fantastic stuff and don’t know how to sing fa la la la la. . . . Some ask for canzonets and some want recitatives, some sacred, some lascivious, and some full of tales; you assure each one that these are verses and not gold pieces; if they wanted so many coins even all Peru could not satisfy!

Singing in Italy must have had a social function similar to the role that athletics plays in our society today: a popular, stimulating pursuit for amateurs, a medium for self-improvement, a highstakes career track that could take a lucky few out of the ghettos into the most glittering social circles, and a source of wonder and admiration for the audiences who relished the awe-inspiring achievements of the pros. The young Handel had the good for tune to enter this intensely vocal culture at the very top of the heap. His entrée into Italian society was through the Medici family; hence his first stop in the peninsula was Florence. It was in Rome, however, that Handel found the most fertile grounds on which to cultivate his musical genius. Handel was housed and patronized there by Marchese Francesco Ruspoli, who introduced him to the Academy of the Arcadians, an influential circle of noblemen and clerics with interests in literary reform and music. At the Academy, Handel’s cantatas were performed by some of the finest musicians in Europe (including Arcangelo Corelli and the soprano Margherita Durastante) and heard by a small audience of highly discerning connoisseurs. These intimate occasions seem to have inspired some of Handel’s most exquisitely refined work. Handel’s cantatas resemble their Italian models in that most of the texts are about love, often with pastoral conceits. A relatively small number of exceptional pieces deal with mythological or historical topics (e.g., La Lucrezia).

In the love cantatas, the texts are often bizarrely abstracted. Personal and situational references are stripped away; the lover and beloved are not named or described. What remains is a narrative in which the characters are hearts, souls, eyes, with all of their Petrarchian significance — subject to the alchemical powers of Love personified as the blind archer god. One can only guess what sorts of sublimations were involved in the production and presentation of such poetry in a circle of persons that included a large number of clergy as well as unmarried men and women.

Livy’s History of Early Rome was one of the most widely read books of the seventeenth century. Its themes of personal heroism in opposing despotism made it a favorite in circles with republican ideals. The book includes the dramatic story of Lucretia, a faithful wife whose rape by Prince Tarquin drove her to suicide and inspired the Romans to depose their monarchy and establish a republic. The tale was a favorite theme of artists, poets, and musicians throughout Europe for centuries, with treatments by St. Augustine, Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Tintoretto, Keiser (Handel’s mentor at the Hamburg Opera), Botticelli, and Giambologna, to name only a few. The tale admits innumerable angles for treatment — moral, political, erotic, psychological. Handel’s cantata is a masterpiece of characterization that involves the audience in a harrowing emotional spiral of grief and rage. The heroine’s initial expression of her sorrow and sense of injustice elicits sympathy that only grows as we follow her progression of appeals to hell for vengeance and fits of self-condemnation, culminating in a hateful suicidal frenzy. The survival of an unusual number of manuscript copies suggests that this cantata was one of Handel’s more famous chamber works during his lifetime.

One of the manuscript sources of Sonata in C Major bears conflicting attributions to Handel and to the Nüremburg organist Johann Michael Leffloth (1705 –1731). Both attributions are considered unreliable on stylistic grounds. Regardless of authorship, this charming piece is valued in par t for its unusual treatment of the harpsichord in a virtuoso role, something rarely found in chamber music of this period. The arias “Non saria poco” from Atalanta and “Spera si mio Caro” from Admetus are presented here in transcriptions originally published by the prolific London music printer, John Walsh. Star ting in 1739, Walsh became Handel’s exclusive publisher, and produced dozens of prints of the composer’s operas, oratorios, concer tos, and chamber music. Some of these publications seem to have had scant supervision by Handel. These offerings were principally designed not for use by professional musicians, but rather for domestic use. As such, they bear testimony to the public’s craving for this music, and the satisfaction listeners had in savoring Handel’s fine airs in the intimacy of a musical household.

The impulse to enjoy the most memorable moments of operas in homemade renditions was not confined to amateurs and “wanna-bes,” however. Handel himself could not resist. The harpsichord transcription of “Sventurato godi, o core abbandonato” from Floriodante comes from an autograph manuscript and represents Handel’s own recasting of the gestures of this moving opera air in his own favored performance medium.

Album Details

Total Time: 79:00

Recorded: September 3-6, 2000 at WFMT Chicago, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: “The Artist and his Family in Concert” by David the Younger Teniers (1610-1690). Courtesy of Noortman, Maastricht, Netherlands / Bridgeman Art Library.

Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: John Mark Rozendaal

© 2001 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 057