| Subtotal | $12.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $0.92 |

| Total | $9.92 |

Store

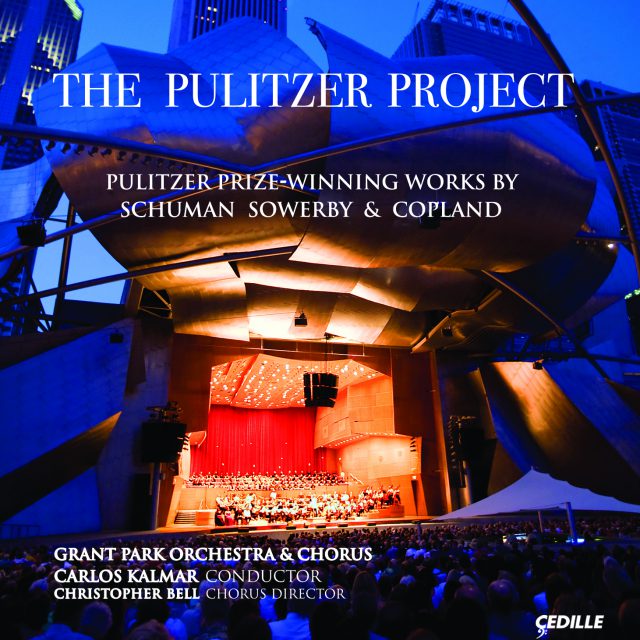

The Pulitzer Prize in Music, established in 1943, is perhaps the most coveted award in American concert life. This new CD with Chicago’s Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus and principal conductor Carlos Kalmar presents three Pulitzer Prize-winning works from the competition’s earliest years: William Schuman’s Secular Cantata No. 2, “A Free Song”; Aaron Copland’s Suite from Appalachian Spring; and Leo Sowerby’s The Canticle of the Sun for chorus and orchestra. These are the world-premiere recordings of the Schuman and Sowerby cantatas.

William Schuman’s A Free Song, winner in 1943 of the first Pulitzer Prize in Music, uses excerpts from Walt Whitman’s Drum Taps, a poetic record of his humanitarian visits to Washington, D.C.’s Civil War hospitals. Schuman (1910-1992) set Whitman’s vigorous, expansive verse to a fierce and concentrated musical style. In its review of the Grant Park Orchestra’s 2010 concert performance, the Chicago Tribune observed, “Kalmar’s account was, by turns, poignant and electric.”

One of the most recognizable and beloved American orchestral works, Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring began life as a ballet score for the Martha Graham Dance Company. A favorite of many listeners is its five variations on the Shaker theme “Simple Gifts.” The original ballet score, for chamber orchestra, won the 1945 Pulitzer Prize. Copland (1900-1990) later arranged an orchestral suite, its most familiar incarnation and the one heard on this CD.

Based on St. Francis of Assisi’s 13th-century hymn praising God and his creations, Sowerby’s The Canticle of the Sun won the 1946 Pulitzer. Sowerby (1895-1968) was attracted to the text because of its opportunities for musical color. The program annotator for the Canticle‘s 1945 world premiere at Carnegie Hall wrote, “He has made of it a panorama of all the elements of heaven and earth . . . it unfolds in a series of tonal pictures, each motivated by the phase it describes.” Chicago Classical Review‘s Lawrence Johnson wrote in a concert review, “Under Kalmar’s firm, incisive direction, the Canticle opens with impassioned sweep in the orchestra.” Canticle “shows Sowerby’s confident handling of orchestra and voices, often drawing a striking organ-like sonority from the instrumental choirs.” </p

Preview Excerpts

A Free Song (1943 Pulitzer)

Appalachian Spring (1945 Pulitzer)

The Canticle of the Sun (1946 Pulitzer)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Pulitzer Project

Notes by Dr. Richard E. Rodda

Joseph Pulitzer, born in Hungary in 1847 and well educated in Budapest, decided to become a soldier when he was seventeen. Unable to get into the military of Austria, Britain, or France due to poor eyesight and frail health, he encountered a bounty recruiter for the United States Army in Hamburg and enlisted as a substitute for an American draftee who had paid to escape service in the Civil War. Legend has it that Pulitzer jumped overboard as his ship sailed into Boston harbor, swam to shore, and collected the bounty for himself. Pulitzer eventually made his way to St. Louis, where he impressed the owner of a local German-language newspaper during an impromptu chess game at the city’s Mercantile Library in 1868 and got hired as a reporter. Pulitzer was a diligent and enterprising journalist, and within four years became the paper’s publisher. Shrewd business deals and tireless work brought him ownership of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1878. Through populist appeal, crusades against public and private corruption, and ingenious promotions, the Post-Dispatch flourished. Thanks to this success, Pulitzer was able to buy the struggling New York World from financier Jay Gould in 1883. Pulitzer used the same business formula in New York that had worked in St. Louis (one of his promotions raised funds for a pedestal so that the Statue of Liberty could be erected in New York harbor) and made the World into one of the nation’s leading newspapers despite frequent controversies, ferocious competition, and his own fragile health.

Among Pulitzer’s bequests upon his death, in 1911, was $2 million to establish a school of journalism at Columbia University; one-fourth of that amount was to be “applied to prizes or scholarships for the encouragement of public service, public morals, American literature and the advancement of education.” The first Pulitzer Prizes were awarded in 1917 “to honor excellence in journalism and the arts.” The original award categories were for biography or autobiography, history, editorial writing, and reporting; fiction, drama, and public service were added a year later. Categories have continued to change over the years, including the addition of an award in 1943 “for a distinguished musical composition by an American that has had its first performance or recording in the United States during the year.” The award’s first recipient was William Schuman, for his A Free Song. Pulitzer Prizes for Music in the following three years went to Howard Hanson (Symphony No. 4), Aaron Copland (Appalachian Spring) and Leo Sowerby (The Canticle of the Sun). The Pulitzer has since been recognized as concert music’s most prestigious award. Its recipients include Ives, Menotti, Piston, Barber, Carter, Crumb, Druckman, Rorem, Del Tredici, Sessions, Bolcom, Harbison, Zwilich, Schuller, Kernis, Adams, Reich, Higdon, and many other of the most gifted American composers. The award took on additional significance when its scope was broadened in 1997 to include jazz and other mainstream music: Winton Marsalis won in that year for his “jazz oratorio” Blood on the Fields; Ornette Coleman prevailed in 2007 for Sound Grammar; and George Gershwin, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, and John Coltrane have received special posthumous citations. Though not considered in the music category, some of Broadway’s most memorable shows have received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama: Of Thee I Sing (George and Ira Gershwin), South Pacific (Rodgers and Hammerstein), Fiorello! (Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick), How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying (Frank Loesser and Abe Burrows), A Chorus Line (Marvin Hamlisch and Edward Kliban), Sunday In The Park With George (Stephen Sondheim), Rent (Jonathan Larson), and Next to Normal (Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey).

William Schuman, born in New York City in 1910, was one of America’s most distinguished composers and educators. As a teenager, his interest was in jazz and popular music, but he turned to concert music before leaving high school. Following study at Columbia University and privately with Roy Harris, Schuman joined the faculty of Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York in 1935. The American Festival Overture of 1939 was his first work to gain popular notice. During the ensuing five years, he became one of the leading artistic figures of his generation, receiving the first Pulitzer Prize in music in 1943 for A Free Song. In 1945, he left Sarah Lawrence to assume the dual responsibilities of Director of Publications for G. Schirmer, Inc. and President of the Juilliard School of Music in New York City. At Juilliard, where he remained for eighteen years, his tenure was notable for the establishment of the renowned Juilliard Quartet and for the thorough overhaul of the teaching of music theory. This latter achievement, which influenced the curricula of music schools throughout the country, arose from his philosophy of basing instruction directly on the experiences of listening to and creating music rather than on any rigid pedagogical system. From 1962 to 1969, Schuman served as President of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, a period that began with the opening of Philharmonic Hall and ended with the complex’s completion. He was also among this country’s most prominent spokesmen and advisors for the arts, acting as consultant to, among many others, CBS, the Rockefeller Foundation, Broadcast Music, Inc., and the MacDowell Colony while remaining active as a composer. Thanks to his strict and methodical work schedule, Schuman produced an enormous amount of music for a man of so many parts: ten symphonies; concertante works for piano, violin, horn, cello, and viola; five ballets; an opera; several independent pieces for concert band and orchestra; two dozen choral works; and numerous chamber music scores.

A Free Song (1942) takes its texts from Drum Taps, Walt Whitman’s powerful response to his observations and feelings while volunteering for much of the Civil War in the hospitals of Washington, D.C. The G. Schirmer company’s press release announcing its publication of A Free Song declared, “The vigorous, expansive verse of Whitman finds a congenial association with Schuman’s fierce and concentrated style, where grace and charm are crowded out by the impact of granite-like blocks of dissonant harmony and sharp-edged counterpoint.”

The two contrasted passages from Drum Taps set in A Free Song embody Whitman’s belief in America’s fundamental strength and optimism in a time of great strife. These spoke with special force to a country in the midst of another brutal war in 1943. The first movement concerns the hard truths drawn from a time of national testing: Long, too long, America … you learned from joys and prosperity only, But now, ah now, to learn from crises of anguish. Schuman captured not only the pervasive mood of troubled uncertainty in these words but also the pictorial implications of such phrases as “Traveling roads all even and peaceful” and “Pour softly down night’s nimbus.” The second movement begins with a muscular, rhythmically dynamic fugue that ascends through the woodwinds into the full orchestra to preface the jubilant chorus that distills the expressive essence of Whitman’s heroic verses: We hear the drums beat and the trumpets blowing, A new song, a free song, We hear the jubilant shouts of millions of men, We hear Liberty!

In 1942, one of America’s greatest patrons of the arts, Mrs. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, went to see a dance recital by Martha Graham. So taken with the genius of the dancer-choreographer was Mrs. Coolidge that she offered to commission three ballets specially for Graham. Martha Graham chose the composers: Darius Milhaud, Paul Hindemith, and an American whose work she had admired for over a decade ‚Äî Aaron Copland. In 1931, Graham had staged Copland’s Piano Variations as the ballet Dithyramb, and she was eager to have another dance piece from him, especially after his recent successes with Billy the Kid and Rodeo. Graham’s scenario based on memories of her grandmother’s farm in turn-of-the-20th-century Pennsylvania proved a perfect match for the direct, quintessentially American style Copland exhibited in those years.

The premiere was set for October 30, 1944 (in honor of Mrs. Coolidge’s 80th birthday) in the auditorium of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. The theater’s small stage allowed for a chamber orchestra of only thirteen instruments: flute, clarinet, bassoon, piano, and nine strings. Copland began work in June 1943 in Hollywood (while writing music for the movie North Star) and finished a year later in Cambridge, where he was delivering the Horatio Appleton Lamb Lectures at Harvard. The plot, music, and most of the choreography were completed before a title was chosen. Graham was taken at just that time with the name of a poem by Hart Crane ‚Äî Appalachian Spring ‚Äî and she adopted it for her new ballet, although the content of the poem bears no relation to the stage work.

Appalachian Spring was unveiled in Washington in October 1944 and repeated in New York in May to great acclaim, garnering the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Music and the New York Music Critics Circle Award as the outstanding theatrical work of the 1944‚Äì1945 season. Soon after its New York premiere, Copland revised the score as a suite of eight continuous sections for full orchestra, eliminating about eight minutes of music in which he said, “the interest is primarily choreographic.” On October 4, 1945, Artur Rodzinski led the New York Philharmonic in the premiere of this version, which has become one the best-loved works of 20th-century American music.

Edwin Denby’s description of the ballet’s action from his review of the New York premiere in May 1945 was reprinted in the published score:

[The ballet concerns] a pioneer celebration in spring around a newly built farmhouse in the Pennsylvania hills in the early part of the 19th century. The bride-to-be and the young farmer-husband enact the emotions, joyful and apprehensive, their new domestic partnership invites. An older neighbor suggests now and then the rocky confidence of experience. A revivalist and his followers remind the new house-holders of the strange and terrible aspects of human fate. At the end, the couple are left quiet and strong in their new house.

Copland wrote:

The suite arranged from the ballet contains the following sections, played without interruption:

- Very Slowly. Introduction of the characters, one by one, in a suffused light.

- Fast. Sudden burst of unison strings in A-major arpeggios starts the action. A sentiment both elated and religious gives the keynote to this scene.

- Moderato. Duo for the Bride and her Intended — scene of tenderness and passion.

- Quite fast. The Revivalist and his flock. Folksy feelings — suggestions of square dances and country fiddlers.

- Still faster. Solo dance of the Bride — presentiment of motherhood. Extremes of joy and fear and wonder.

- Very slowly (as at first). Transition scene to music reminiscent of the introduction.

- Calm and flowing. Scenes of daily activity for the Bride and her Farmer-husband. There are five variations on a Shaker theme. The theme, sung by a solo clarinet, was taken from a collection of Shaker melodies compiled by Edward D. Andrews, and published under the title “The Gift To Be Simple.” The melody I borrowed and used almost literally, is called “Simple Gifts.” It has this text:

‘Tis the gift to be simple,

‘Tis the gift to be free,

‘Tis the gift to come down

Where we ought to be.

And when we find ourselves

In the place just right,

‘Twill be in the valley

Of love and delight.

When true simplicity is gain’d,

To bow and to bend we shan’t be asham’d.

To turn, turn will be our delight,

‘Til by turning, turning we come round right.- Moderate. Coda. The Bride takes her place among her neighbors. At the end the couple are left “quiet and strong in their new house.” Muted strings intone a hushed, prayer-like passage. The close is reminiscent of the opening music.

Program annotator for the Grant Park Music Festival, Dr. Richard E. Rodda received a prestigious 2010 ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for his program note for Elgar’s The Dream of Geronitius, published in the program book of the Festival. Dr. Rodda has also provided program notes for many of the world’s top orchestras and musical institutions and liner notes for numerous major and independent classical record labels. Dr. Rodda teaches at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music.

Leo Sowerby's The Canticle of the Sun

Notes by Francis Crociata

“CONGRATULATIONS ON THE PULITZER AWARD. NOW YOU’LL BE HARDER TO SELL THAN EVER.”

This tongue-in-cheek message from his publisher, William Gray, arrived slightly ahead of the telegram from the Trustees of Columbia University. Thus Leo Sowerby learned he had received the 1946 Pulitzer Prize for his cantata The Canticle of the Sun, his setting for mixed chorus and orchestra of Matthew Arnold’s translation of the famous St. Francis of Assisi poem. The selection committee for the 1946 Pulitzer included two previous Pulitzer recipients, Howard Hanson (1944, for his Symphony No. 4) and Aaron Copland (1945, for Appalachian Spring), and Columbia University factotum Chalmers Clifton.

The Canticle of the Sun was commissioned by the Alice M. Ditson Fund, which is administered by Columbia University (as is the Pulitzer Prize). Sowerby received the commission at Christmas-time, 1942. For a $1000 stipend, he was to produce a choral-orchestral work of 15‚Äì30 minutes duration on whatever text he chose, secular or sacred. Sowerby considered setting two different texts: the Benedicite (canticle from the Book of Daniel used in Anglican and Catholic daily prayer) and Francis Thompson’s “Hound of Heaven,” but settled on the Arnold translation of St. Francis’s canticle, on which Leo’s friend Mrs. H.H.A. Beach had already fashioned a version for chorus and organ. (After Sowerby’s setting came ones by Seth Bingham and Roy Harris.)

At the time of the commission, the 48-year-old composer had enjoyed a 30-year run as the Chicago Symphony’s de facto composer-in-residence, a status effectively ended two months earlier with the death of his champion, longtime CSO conductor Frederick Stock. Sowerby was beginning to have difficulty finding publishers for his solo and chamber works, while H.W. Gray published every piece he wrote for organ and/or chorus as fast as they emerged from his pen. Perhaps for this reason, Sowerby always insisted that Canticle was a secular concert work, belonging to his imposing body of symphonies, concertos, and chamber works, distinct from his equally sizable group of compositions for the church, for which he is mainly remembered today.

Over a life span of 65 years, The Canticle of the Sun has received only a dozen performances ‚Äî and most of those were of Jack Ossewaard’s odd, yet surprisingly effective, arrangement for organ, two pianos, brass, and percussion. Sowerby’s original orchestration was heard at the New York premiere, two composer-led performances in the early 1950s, and the pair of 2010 Grant Park Music Festival performances documented by this recording. Nonetheless, Leo’s Canticle was his good luck piece. It kept his name before the public when his regard among symphony conductors and soloists was waning. It prompted the 1954 invitation for Sowerby to conduct the Chicago Symphony. In 1953, Leo’s conducting of Canticle with the National Symphony and Cathedral Choral Society in Washington set in motion a chain of events including his commission for The Throne of God to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Washington Cathedral in 1957. The Cathedral Rector, Francis Sayer, was explicit in asking for a work modeled in scope and sonority on The Canticle of the Sun. The Cathedral performances of Canticle and Throne made Sowerby’s selection as the first director of the Cathedral’s College of Church Musicians an inevitability.

The Canticle of the Sun was originally envisioned for the 1944 Worcester Festival but, for reasons this writer has been unable to discover, that performance never materialized and Canticle was premiered instead at a Carnegie Hall benefit for the Armed Forces Recording Service on April 16, 1945. A slightly reduced New York Philharmonic joined the Schola Cantorum, conducted by Hugh Ross, which also performed a Mozart Mass, Holst’s Te Deum, Randall Thompson’s Testament of Freedom, and a setting by Charles Martin Loeffler, for soprano and orchestra, of the St. Francis poem in its original Italian. Hugh Ross, in consultation with Sowerby, wrote for the occasion:

No doubt the subject appealed to the composer because of its opportunities for musical color. He has made of it a panorama of all the elements of heaven and earth which join in praising their creator, and it unfolds in a series of tonal pictures, each motivated by the phase it describes. The order of the pictures is determined by the structure of the poem.

The music begins with an orchestral prelude, combining the elements of the chief keys, F, D, and B, in a species of cosmic spectrum. This prelude expounds the main theme of the work, a leaping corrugated scale passage. It motivates the theme of sunlight and fire, undergoes a weird transformation in the music of the moon, is inverted to describe wind and cloud, provides the choral theme for “our mother the Earth,” and comes as a cry of judgment against those “dying in mortal sin.”

Even where it does not provide the thematic content, it is heard brooding over the other music as in the praise for those “who pardon one another” or in the final admonition to “serve God with great humility.” It is fully restated with its attendant choral outburst of praise in the final section to give balance and coherence to the whole plan.

The themes most closely derived from this main subject are those for sun and fire, which, therefore show great similarity to each other. They are both scherzando movements in fast triple time. The section least alike, though still of a chromatic nature, is that “for our sister Water,” where only the final phrase and its accompaniment derive from the opening. But there are certain passages of a totally different character. These occur where St. Francis refers to specifically human elements. The keys also change conspicuously.

The second statement of divine praise is viewed from the human angle ‚Äî (this comes at the end of the first paragraph of the poem). The spectrum fades away, and we have a simple key of F minor changing to E major, until the unmentionable element of the Divine Name merges everything into a conglomerate harmony once more. “Our sister the Death of the Body” is typified by a direct phrase of lamentation. Those who walk by the Divine Will are described in a veiled walking rhythm and a serene choral phrase is reserved for those “who pardon one another,” and who “serve in great humility.”

This latter phrase, in its final form, is sung in a pure example of the Lydian mode. This mode is especially important, as it characterizes every single theme and section except that of those who pardon one another, and in its last version, mentioned above, has an extraordinary effect as of looking upwards in complete serenity.

Sowerby’s Canticle elicited widely varied reactions from the New York critics. In New York PM, musicologist Paul Henry Lang described the music and its creator approvingly as “Like Delius through stained glass.” In the Times, Olin Downes cited the sophistication of Sowerby’s setting in preference to Loeffler’s. In the Herald-Tribune, Virgil Thomson took the opposite view, dismissing Sowerby’s score as Wagnerian-Lisztian. The audience included former Sowerby student Ned Rorem and a young composer for whose Prix de Rome candidacy Sowerby had advocated: Samuel Barber. Barber’s later penned a touching tribute to his older colleague: “Dammit, Leo, I wish I could write for chorus like you!”

Francis Crociata has been president of the Leo Sowerby Foundation since 1993 and works in the advancement division of Saint Leo University in Florida

Album Details

Total Time: 74:00

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineers: Eric Arunas, Bill Maylone

Patch Session Director: Christopher Bell

Cover: Grant Park Orchestra & Chorus performing in Chicago’s Jay Pritzker Pavilion at night, photo by Norman Timonera

Recorded in concert at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance in Millennium Park, Chicago, June 25 and 26, 2010

Art Direction: Adam Fleishman – www.adamfleishman.com

Made possible in part by grants from The Aaron Copland Fund for Music and the Leo Sowerby Foundation

© 2011 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 125