Store

Store

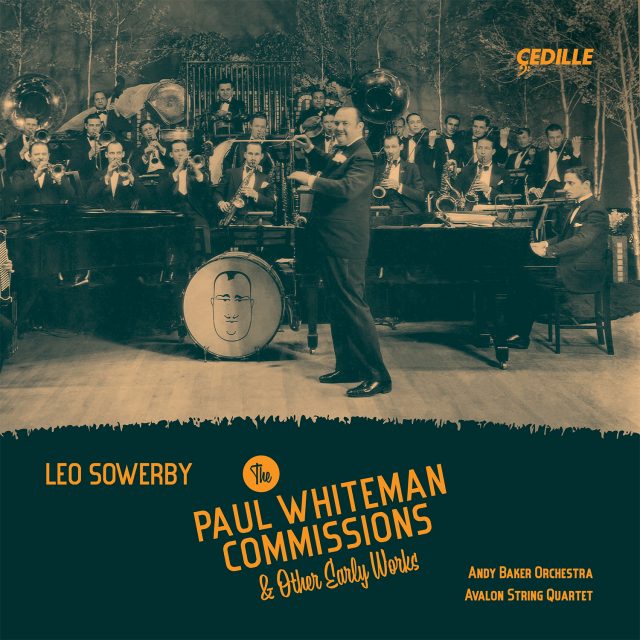

Leo Sowerby: The Paul Whiteman Commissions & Other Early Works

Andrew Baker/Andy Baker Orchestra, Avalon String Quartet, Winston Choi, Alexander Hanna

Evoking the Roaring Twenties, Chicago composer Leo Sowerby’s engaging and ingenious Synconata (1924) and Symphony for Jazz Orchestra (“Monotony”) (1925), critically praised for their distinctive harmony, counterpoint, and humor, receive world-premiere recordings by Chicago bandleader-trombonist Andrew Baker and his Andy Baker Orchestra, making their Cedille Records debuts.

Sowerby was among the leading young American classical composers commissioned by celebrity bandleader Paul Whiteman to create fresh repertoire for his landmark series of “symphonic jazz” concerts — a roster that also included George Gershwin, Ferde Grofé, and Zez Confrey.

The same Jazz Age concerts that saw the premieres of Sowerby’s Synconata and Symphony for Jazz Orchestra also launched Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue into America’s consciousness.

The program also includes Sowerby chamber works from the same period: his Serenade for String Quartet and the world-premiere recordings of his String Quartet in D minor and Tramping Tune for piano and strings, all performed by the Avalon String Quartet, an ensemble “prizing grace, charm and elegance” (WQXR Radio). Joining the Avalon in Tramping Tune are pianist Winston Choi, head of the piano program at Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts, and Alexander Hanna, principal double-bassist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

This recording is made possible in part by grants from the Leo Sowerby Foundation and the University of Ilinois at Chicago College of Architecture, Design, and the Artts School of Theater and Music.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview with

Andy Baker & Avalon String Quartet’s Anthony Devroye

on Cedille’s Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

LEO SOWERBY (1895–1968)

String Quartet in D minor H 172 (1923)

Symphony for Jazz Orchestra (“Monotony”) H 178 (1925)

Artists

1: Andy Baker Orchestra / Andrew Baker

2: Avalon String Quartet

3: Avalon String Quartet

6: Winston Choi, piano; Avalon String Quartet; Alexander Hanna, double bass

7: Andy Baker Orchestra / Andrew Baker

Program Notes

Download Album BookletLeo Sowerby: The Paul Whiteman Commissions & Other Early Works

Notes by Francis Crociata

Before we consider the music on this recording — selected compositions by Leo Sowerby spanning the decade from 1916 to 1925 — I must take a moment to acknowledge the unusual challenges of making the sounding of these particular works possible. Specifically, I would like to commend the work of Andrew Baker and the members of the Avalon String Quartet, all of whom did far more than “just” perform these scores with great instrumental virtuosity and sensitivity to style. They were called upon to make a variety of creative judgements in order for these pieces to work musically and emotionally. In his quest to evoke the sound and virtuosity of Whiteman’s famous band, Andrew Baker had to bring all his experience as a band-leader and session player to bear to navigate the difficulties presented by two sets of scores and parts often in disagreement with one another. The challenge to the Avalon String Quartet was even greater, essentially calling upon the players to assume the role of co-creators.

On July 6, 1968, the day before he died, Leo Sowerby laid down his pencil for the last time. He had just completed his final work, a set of organ variations. While he left most of his catalogue of 550 works in good order, about 30 of his known works were missing either their full scores, or solo or orchestral parts, or were otherwise in a state that made their performance or publication problematic. Four of these, Synconata, the Symphony for Jazz Orchestra (“Monotony”), String Quartet in D minor, and Tramping Tune, appear on this CD in their first recordings. In fact, the only piece presented here that didn’t require some kind of posthumous “triage” is the Serenade for String Quartet, because it was one of the small number of his concert works engraved and printed during the composer’s lifetime.

The two works commissioned by Paul Whiteman were scored specifically for the individual players in the Whiteman orchestra, most of whom played a variety of instruments — and the names of these instrument-switching performers, such as “Mr. Sharpe” and “McLane,” appear next to their staves rather than specific instruments. To further complicate matters, when Whiteman carried over the pieces in his tour repertory from one season to the next, the conductor called upon Sowerby to re-score, reassigning instrumental lines to different players and, in several instances, changing instrumentation altogether. After Whiteman moved on from his symphonic experiment (except for Rhapsody in Blue, which remained in his repertory), Sowerby’s friends tried to promote the Jazz Symphony and Synconata to established symphony orchestras. Had they been successful, Sowerby might have made a conventional performing edition. But they were not, and the composer made no practical performing edition. So it fell to Maestro Baker to pull both compositions together. With the release of this recording, perhaps some enterprising doctoral candidate will be inspired to take up the challenge of making permanent performing editions of both of these works, so evocative of the Roaring Twenties jazz age.

As mentioned, the challenge for the musicians of the Avalon String Quartet was even more daunting. Right from the Leo Sowerby at age 21 beginning, when Master Leo Sowerby, age 4 ten, composed his first work, his method was to make a pencil sketch, followed by a pencil copy with full notation but little in the way of tempo and dynamic indications, followed by an inked copy meticulously annotated. The vast majority of his choral and organ works were then sent off to publishers for engraving. But only a small fraction of his solo, chamber, and orchestral works were ever engraved and published, so his inked copies would be used for both study and performance, often circulating beyond his immediate control. At the time of his passing, unaccounted for were the inked scores for his first piano concerto, two of his violin sonatas, the orchestral tone poem Theme in Yellow (a new conductor’s score was reconstructed from the orchestral parts for Paul Freeman’s two-CD Cedille edition of selected symphonic works), and both mature string quartets. These and other missing scores may turn up eventually and, indeed, one of the missing violin sonata manuscripts was recently found when the Library of Congress finished cataloging its collection of scores belonging to Jascha Heifetz, received upon the great violinist’s passing two decades before.

For the String Quartet in D minor, the Avalon musicians worked from an engraved score made from the pencil copy and carefully proofread by two of Sowerby’s former students. So they had all the notes but only the descriptive movement headings — no dynamics, accents, or bowings. And, in fact, they wouldn’t even have had those movement indicators had we not found copies of concert programs from a handful of performances from the 1920s and 30s. So all the Avalon had to go on were published scores of other string pieces from around the same time, their experience in performing the published Serenade, and suggestions from former Sowerby students Michael McCabe and Ronald Rice and experienced Sowerby instrumental performers Neal Campbell and James Winfield, with whom they shared iPhone recordings of their rehearsals in the run-up to the recording.

Have they recreated the Sowerby String Quartet in D minor as the composer (or anyone else) last heard it on March 1, 1937 in the foyer of Chicago’s Orchestral Hall? Unless the inked manuscript is found, we shall never know for sure. But until then, to my ears and heart, they have given us an intelligent, committed, and moving account that communicates its creator’s lyric gift and fertile imagination. I can only hope that they, or some other quartet having their qualities, will someday render the same service for Sowerby’s later (and larger) String Quartet in G minor.

SYNCONATA H 176a (1924)

MONOTONY: A Symphony for Metronome and Jazz Orchestra H 178 (1925)

I. “Nights Out” The Weary Babbitt—The Invitation Out—The Ineffectual Protest — Table d’hote—Aisle Seats—The Snore — Relapse — Snatched Home

II. “Fridays at Five” Chatter — Pekoe and Pique — Neurasthenics — Choice Bits — The Scandal — tst-t-t-t-t

III. “Sermons” Voluntary — Warming Up —The Offertory — Full-Cry — Working to Beat Hell

IV. “Critics” Enter the Chairmen of the Board — The Sycophant — The Sentimentalist — The Fussbudget — The Ancient Mariner — The Sophisticate — Orpheus at Bay

Leo Sowerby, says a note from Eric DeLamarter, is in a fair way to become a jazz hound. A recent trip east has been prolonged because he met Paul Whiteman, and “Paul seduced him into trailing with that gang as far as Boston.” There are certain indications that one of his next moves will be to write another piece for the Whiteman orchestra. This, says Mr. DeLamarter, is an epochal fall from the holy state of sanctification, in whose mystic beatitudes live only those owning the sky scraper frontal bone. — Gossip column, Chicago Tribune, May 3, 1925

A pivotal moment in American music history occurred on November 24, 1924. Paul Whiteman, the larger-than-life society band leader, brought his jazz orchestra from Los Angeles to New York City’s Aeolian Hall to perform the first of what he called his “Revolutionary Concerts,” conceived to give Americans, particularly young composers interested in mining native idioms such as jazz, gospel, and folk music, the kinds of opportunities to be heard that their European counterparts took for granted.

One composer on that first program took his opportunity to the bank. Although incomplete and first orchestrated by other hands, George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue was played by popular demand on every subsequent “Revolutionary” concert (and thousands of times since). That first program brought together arranged works of Zez Confrey (“Kitten on the Keys”) and John Alden Carpenter (“Krazy Kat”), and arrangements by Ferde Grofé and Whiteman himself. One critic, Deems Taylor, a composer himself, lamented the dearth of material for Whiteman’s revolution, titling his article, “All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go.” In interviews and his own article in Vanity Fair titled “The Progress of Jazz,” Whiteman promised he would see to it that there would be somewhere to go: “We will even have some good music — for the best men we have in America today — men like Carpenter, Sowerby and Taylor are convinced of the really great art and educational value of jazz treated with a serious intent.”

One of the first men Whiteman turned to was Chicago’s Leo Sowerby, who was already the most frequently performed classically trained American composer. Most significantly, Sowerby had been incorporating jazz and folk music into his musical vocabulary since the mid-1910s. Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan on May 1, 1895, and recognized as a musical prodigy by the time he was ten, Sowerby’s parents sent him to Chicago in 1909 to pursue a conservatory education. He made that city his home, teaching at his alma mater, the American Conservatory of Music, and serving as organist-choirmaster at St. James Episcopal Cathedral, picking up the 1946 Pulitzer Prize for Music along the way and leaving Chicago in 1962 to become founding director of the College of Church Musicians at the National Cathedral in Washington.

In addition to those formal appointments, beginning in 1917 and continuing until the passing of conductor Frederick Stock in 1942, Sowerby enjoyed an even more significant position of prominence as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s de facto composer-in-residence. Largely self-taught as a composer, by the time of his passing in 1968, Sowerby had composed 550 works, as he put it “in all forms except opera.” Beginning with the premiere of his Violin

Concerto in 1913 (at age 18), more than a dozen Sowerby scores were premiered by the Chicago Symphony, including his first three symphonies, his violin and first piano concertos, and a host of suites and tone poems. He was frequently heard as a pianist and organist on the Chicago scene, and quickly gained national and international attention both as performer and composer. When the American Academy in Rome introduced a three-year fellowship in music in 1921, Leo Sowerby received the first appointment without having to compete, based on the reputation his works had already achieved. He was joined there by the first competition winner, his lifelong friend Howard Hanson.

When Sowerby returned from Rome in fall 1924, he was contacted by Paul Whiteman. Classically trained, Whiteman had formed his own “jazz” orchestra in Los Angeles and hit upon the idea of writing out parts for his musicians instead of the usual improvisation. Among the performers who were at one time or another part of the Whiteman Orchestra were Bix Beiderbecke, the Dorsey Brothers (Tommy and Jimmy), Joe Venuti, and Henry Busse.

Whiteman asked Sowerby for a work of symphonic jazz in a recognizable classical form and the composer responded with a one-movement sonata he named (at the advice of advertising agency chief Arthur Kudner) Synconata, with a second theme (unwittingly and unmistakably) foreshadowing Cy Coleman’s “If My Friends Could See Me Now” from the 1966 Broadway hit, Sweet Charity. Synconata’s premiere at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House on December 28, 1924, was warmly received by audience and critics, and the piece was taken on a 100-city transcontinental tour. Shortly afterward, Sowerby arranged the piece for the duopiano team of Guy Meier and Lee Mattison (a version you can hear performed by Gail Quillman and Julia Tsien on Cedille 7006).

The New York Sun’s music critic wrote of the premiere: “Sowerby’s impressive rushes of chords were often amusingly interrupted by ironic chuckles and snickers from the muted clarinets and saxophones.” When Synconata was heard in Chicago in April 1925, the Tribune’s veteran critic, Edward Moore, wrote: “in what it is trying to be, it is considerably better than Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ which, effective as it is, has always struck me as being agglutinative rather than cohesive. The Synconata is quite as effective and better music.”

This last comment, though well-meant by Moore, a longtime Sowerby-partisan, probably did Synconata and its composer a disservice, creating an unreasonable expectation. George Gershwin, who Sowerby said taught him to drink martinis, was a jazz musician first, last, and always — at home in the idiom. Sowerby was a visitor, often hinting at jazz harmonies and rhythms in unexpected surroundings such as the sublime organ works and choral anthems for which he is best-remembered today. Whiteman, himself, also meant well but did the composer’s professional reputation no favor when he told a Washington Evening Star interviewer he considered Leo Sowerby a greater genius than Igor Stravinsky.

With the resounding success of Synconata, Whiteman requested a larger work for his tour the following season. Sowerby wrote for him a “Symphony for Metronome and Jazz Orchestra,” entitling it ironically and, as it turned out, unfortunately, “Monotony.” Sowerby often stated he didn’t write opera, or in fact anything for the stage — no ballets, no incidental music for dramatic works. That isn’t quite true. “Monotony” was conceived as a stage work, the centerpiece of which was a 6’5” metronome from which the title “Monotony” was derived. Whiteman, who was 6’4” tall (and nearly as broad of girth) conducted (from the audience’s perspective) from behind the metronome. The metronome’s arm was

set to swing silently at a constant 40-beats per minute through the entire work. The beat was subdivided in various ways, so as to draw attention away from the great variety of tempos Sowerby actually called for. Nino Ronchi designed a set in front of which was a scrim on which interlocking rotating gears were projected. The band was costumed, as was a woman carrying placards bearing movement titles and subtitles, such as would be seen at a Vaudeville theatre or silent movie. I can find no evidence that the whole multi-media show ever worked or was even attempted after the premiere (which occurred after a Kalamazoo, Michigan “preview”) in Chicago’s Auditorium Theatre on October 11, 1925.

Sowerby’s Symphony for Jazz Orchestra (and would that he had called it only that!) was not only a theatre piece; it had a literary subtext: Sinclair Lewis’s best-selling 1922 novel, Babbitt, the portrayal of a businessman who conforms unthinkingly and complacently to prevailing, and often pretentious, middle-class standards of respectability. Babbitt makes the attainment of material success his religion and is utterly incapable of appreciating artistic or intellectual values. The Symphony’s four movements follow along as the work-weary Babitt is dragged against his will to the theater (“Nights Out”), to a cocktail party-masquerading as a tea party — this being at the height of Prohibition (“Fridays at Five”), to Sunday services (“Sermons”), and to a concert, the content and quality of which is explained to him in the following day’s newspapers by six archetypical music critics (“Critics”).

In perusing the several dozen reviews I could find, I’ve come to the conclusion that “Monotony” was for many critics and audience members, in theatrical terms, a “flop.” Audiences were disappointed that the piece was not another Rhapsody in Blue, the concluding piece on every program on which either Sowerby commission was performed. It didn’t matter to 1925–1926 Paul Whiteman audiences that “Monotony” was never intended by its composer, or the man who commissioned it, to be another Rhapsody. And if the title itself weren’t an inviting enough target for critics to use as their review’s springboard (and several did not resist the temptation), the fourth moment send-up of their profession was, at the very least, an imprudent move for even so well-established a young composer as Sowerby. I imagine several of the negative notices were penned by critics feeling a bit prickly, but the critic of the Louisville Courier-Journal (“A.L.H.”) took explicit personal umbrage and penned a protean example of early 20th-century critical invective: “Mr. Whiteman did the best he could for this composition, explaining the programme in detail, from the first barbaric yawp of the Tired Business Man doomed to attend the theater against his will through the brassy chat of 5 o’clock tea and the soothing murmer of a sermon to the noisy and unflattering portraits of four [sic] critics, who probably had the same opinion of Mr. Sowerby’s music as that expressed by the present writer.”

Although it didn’t work as a theater piece — probably confirming Sowerby’s own conviction that he wasn’t “a man of the theater” and never would be — shorn of “special effects” and even of the title “Monotony” (which Whiteman dropped in the last few performances, calling it simply “Jazz Suite”), Leo Sowerby’s Symphony for Jazz Orchestra, like the overture-length Synconata, emerges from the mists of time as an engaging, ingenious, virtuosic piece of symphonic music. It may not be as sublime as Sowerby’s greatest masterpieces such as the Organ Symphony; the Lenten cantata, Forsaken of Man; and (the very next work in the Sowerby canon after the Whiteman commissions) his sublime Medieval Poem for organ and orchestra — works that have never fallen out of the repertory. But as with his still mostly overlooked body of symphonic, instrumental, and vocal music, performers today would certainly find visits with Sowerby’s Whiteman commissions to be as rewarding for themselves and their audiences as their forays into most regularly programmed works by other American composers of the first half of 20th-century. (At the sessions for these recordings, many of the musicians, especially the younger ones, expressed astonishment that the composer of this music was so obscure.)

Following the Auditorium Theater premiere performance of the Symphony for Jazz Orchestra, one of Sowerby’s critical champions, Glenn Dillard Gunn, wrote in the Chicago Herald-Examiner: “It was concerned, its whimsical and sometimes subtle humor apart, with much brilliant contrapuntal technique, with a gorgeous sense of instrumental color.” As the Whiteman orchestra repeated “Monotony” from coast to coast, other critics described the work as “exceedingly eccentric and amusing,” “fourth dimensional jazz,” “a satire on the machine age, in the form of a tonal nightmare,” and “the symbolic composition which may herald the advent of the long-awaited new American music.”

Gunn’s extended review perfectly diagnosed the problem for Sowerby’s jazz orchestra works: Paul Whiteman might have been the right man to commission, and even to perform Synconata and “Monotony,” but his audience was the wrong one to receive it. Gunn postulated that their performance histories would have been very different had they started life in the hands of Sowerby’s greatest champion and benefactor, the Chicago Symphony’s Frederick Stock:

Let it be stated at once that Sowerby’s symphony for metronome and jazz orchestra called “Monotony,” which had its first hearing, would have had an enormous success with the Saturday evening audiences at Orchestra Hall. It is clever, racy, daring, funny without being grotesque. It is a bit too long even for a symphony audience, but Mr. Stock would have remedied that fault before it came to performance.… In Orchestra Hall, let me repeat, it would have been a great success.

I hope these recordings will inspire some enterprising symphony orchestra to put Mr. Gunn’s 20th-century premise to the test with their 21st-century subscription audiences.

When Cedille originally committed to recording the two jazz works Paul Whiteman commissioned from Leo Sowerby and engaged trombonist/bandleader Andrew Baker to direct the recording, the remainder of the disc was to comprise two large, jazz-infused works for concert band, Spring Overture (which quotes “It Ain’t Necessarily So” from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess) and American Rhapsody, and the briefer, Ivesian/Graingeresque romp, Tramping Tune, in its concert band version. Once again, missing scores beset the project: the score and parts for Spring Overture disappeared after it was played by the Goldman Band in 1984 and the score of American Rhapsody with it, although, fortunately, a photocopy was made of that. The next repertory proposal would have completed the recording with two major symphonic works not included in Paul Freeman’s two-album survey of Sowerby orchestral works for Cedille occasioned by the 1995 Sowerby Centennial. Again, a delay occurred when instrumental parts for Portrait: Fantasy in Triptych, last played by the Indianapolis Symphony in 1953, could not be found and had to be re-extracted. And then COVID-19 arrived to turn the whole world upside down. Recording a 50-piece orchestra was off the table. One of Cedille’s acclaimed recording ensembles, the Avalon String Quartet, came to the rescue, learning three works Sowerby wrote during his 20s — all three very much in keeping with the exploratory/experimental spirit of Synconata and “Monotony.”

TRAMPING TUNE H 122c (1916–1917)

Tramping Tune exists in at least five versions and was written coincident with the Chicago arrival of Australian composer-pianist Percy Grainger. Grainger became teacher, mentor, colleague, and friend to the young Sowerby. He encouraged Sowerby to explore not only contemporary works by traditional “classical” composers, but especially jazz and folk idioms. Grainger also made two introductions crucial in Sowerby’s creative and professional advancement, the music, and eventually the person, of Frederick Delius and the proverbial Godmother of chamber music in America, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, for whom the performance auditorium in the Library of Congress is named.

Tramping Tune began as a song, “Tramping,” recalling Grainger’s penchant for back-packing from concert to concert. “Tramping” then became the solo piano piece Tramping Tune, taking on an almost burlesque quality as close to the style of Charles Ives as Sowerby ever came. Lest we miss this point, Sowerby penned the following subtitle to the piano score, completed on October 16, 1916 (and repeated it in all subsequent arrangements): “Descriptive of political rally times, off key bands, street corner harangues, stirring come-along spirit.” The work’s performance indication was in the picturesque (English) language inherited from Grainger that became a life-long Sowerby trademark: “Poundingly, but not fast. Whole-souledly.”

In January 1917, as the inevitability of entry into the European war gripped the nation, Sowerby arranged Tramping Tune for “piano and string orchestra or solo strings” and played that version in Chicago’s Armour Square on Valentine’s Day, 1917 with strings from the Chicago Symphony. (No piano/strings score exists. The composer apparently banged out the solo piano version together with the separately scored string ensemble, the approach taken here.) Finally, as Sowerby (on Grainger’s advice) learned to play the clarinet in the event he were to be drafted into the Army, he made one more arrangement of Tramping Tune, this time at the recommendation of another mentor: the composer/conductor/organist/critic Eric DeLamarter, then Frederick Stock’s assistant conductor at the Chicago Symphony. This score — itself with five variants from wind ensemble to full concert band to symphony orchestra — bears this inscription: “Arranged Dec. 8, 1917, 7 a.m. Enlisted U.S. Army, 9 a.m., Dec. 8, 1917.”

SERENADE IN G MAJOR FOR STRING QUARTET H 137 (September 1917)

The organ and, later, orchestral overture Comes Autumn Time and this Serenade for String Quartet were the works by which Leo Sowerby was introduced to the wider world of music. In the latter case, Percy Grainger was the lynchpin. Later in life, Sowerby was increasingly vague about the nature of his study with Grainger. The rare times he did mention Grainger, he generally described what were ostensibly piano lessons as little more than repertory “bull sessions.”

Nonetheless, the documentary evidence makes clear Grainger’s importance to Sowerby and his music during this early period of his creative life. The starting point was their mutual love of the three Organ Chorales of Caesar Franck and the weaning of Sowerby, then still more pianist than organist, from what Grainger felt was an unhealthy passion for German organ literature in general and the music of Max Reger in particular. Grainger gave Sowerby his first significant engagement outside the Midwest: the chance to perform one of the two solo piano parts of Grainger’s The Warriors at Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge’s Berkshire Music Festival in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. There, the 21-year-old Sowerby became the first of a host of young Americans to be “adopted” by Mrs. Coolidge, her adoption taking the form of a major commission fulfilled by Sowerby’s First Piano Concerto. (In its original version, the concerto included a vocal part for a female singer, possibly intended for Mrs. Coolidge herself, later removed when he revised the concerto to its final form in 1919). The Coolidge commission enabled Sowerby to buy a building lot and to erect on it a summer cottage/cabin in the resort community of Palisades Park, Michigan. There, on the weekends of September 22–23 and 29–30, he wrote the Serenade, containing elements of folk music influenced by concerts of the touring folk trio of English sisters Dorothy, Rosalind, and Cynthia Fuller. Sowerby inscribed the score, “To my friend, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge – A Birthday Gift for 1917.”

Performances of the Serenade and Comes Autumn Time became Sowerby’s calling cards, and their early publications carried Sowerby’s name to Europe and Great Britain for the first time. The story of receiving the first American Prix de Rome Fellowship without competing for it was the keynote of Sowerby’s “official” biography until he won the Pulitzer Prize a quarter century later. The Serenade, Comes Autumn Time, and the first Sowerby work Frederick Stock commissioned for the Chicago Symphony — A Set of Four: Suite of Ironics (1917) — were, in practical effect, Sowerby’s “competition” pieces, and on them his reputation as the most promising of the new generation of American composers was made.

The Berkshire String Quartet played the world premiere of the Serenade in New York’s Aeolian Hall on March 5, 1918.

The unsigned New York Times review affirmed that Sowerby’s Serenade “proved interesting and novel, raucously so in its shifting harmony, yet relieved by much humor in the interplay of instrumental voices, and by a spirited and songlike theme carried mainly by the first violin.… The piece was not too long, and it did not attempt great fervor of emotion or literalness of description.” The iconoclastic critic James Huneker wrote in the New York Sun:

Mr. Sowerby shows a feeling for the type of melody most readily accepted by Americans — melody leaning toward the Negro idiom and with syncopation of rhythm occasionally close to “rag time.” In treating this melody the young composer displayed good taste, which prevented him from falling into mere cheapness or vulgarity. His part writing was frequently good and sometimes bad, the latter especially when he made some very youthful attempts at bizarre effects in the closing measures.

All his life, but especially in the 1910s and 20s, Sowerby was fascinated by the effects made possible by harmonics and overtones. To this day, I encounter his former students from the College of Church Musicians remembering their measure-by-measure analysis of Ravel’s Sonata for Violin and Cello, a work he adored. He was to make full use of those effects and rhythm and blues in the two large scale String Quartets that would follow the Serenade.

STRING QUARTET IN D MINOR H 172 (January 1923)

In November 1921, the newly-minted first American Rome Prize Fellow departed New York Harbor having already composed 163 opuses, including a symphony and three concertos. By the time he arrived in Le Havre, he had completed his 164th: harmonizations of “La Marseillaise” and “The Star Spangled Banner,” both dated November 11, 1921 — the third anniversary of the Armistice ending World War I. He wasted no time on arrival at Villa Chiaraviglio, home of the American Academy. The terms of the fellowship were loose but clear. He was not a student, but a finished artist. He received room, board, travel expenses, and a stipend. He was expected to interact creatively with the other music fellows (the first actual competition winner, Howard Hanson and, starting the following year, Randall Thompson), to professionally see and be seen, and to write music. By the time he returned to Chicago three years later, 19 works were added to the Sowerby canon, including a violin sonata; a “ballade” for two pianos and orchestra (“King Estmere”); the orchestral suite From the Northland; the bluesy Rhapsody for Chamber Orchestra; and a still-unperformed, five-movement, unnamed symphony for chorus, eight soloists, organ, and orchestra based on the Book of Psalms — a work rivaling in scope, scale, and ambition Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, Busoni’s Doktor Faust, and Scriabin’s The Universe.

And, about midway through his term, he wrote the String Quartet in D minor. With composition in progress, the composer wrote to his former student and lifelong friend Lorry Northrup:

Now that I have returned I have gotten into work again; I am writing a string quartet in three movements, and am now in the middle of the last one, and expect to finish it in a couple of days. That is, the sketch will be finished, but you know that it is always supposed to be very difficult to do a string quartet, and I find it perfectly true, and I know that I shall be mulling it over a lot before I consider it finished. The means are so limited in one way, and yet in another the resources are great. One thing is sure — about such a form there can be no trickery, and no harmonic fluff — it all has to be solid meat. The first movement of this thing will surely bring a howl of protest from some quarters, for it is a glorified fox-trot, with plenty of blues thrown in for good measure.

Sowerby’s Quartet stayed in the repertory for about a decade, until it was supplanted by his larger, more formal/classical response-style Quartet in G minor, written for the Jacques Gordon String Quartet, comprising the concertmaster and principal second violin, violist, and cellist of the Chicago Symphony. The last known performance of the D minor Quartet was in 1937 by the Philharmonic String Quartet, another group of Chicago Symphony string players. For that Chicago Chamber Music Association concert, Sowerby provided this written note, referring to himself in the third person:

The work is rather freely constructed, only the final movement being, more or less, in the traditional Sonata form. The first movement is a sort of “blues,” preceded by a short introduction based on a violent motive, which is the germ of most of the thematic material of the entire work. The second movement is in three sections — slow, fast, slow — and commences in the three upper instruments muted, while the unmuted cello sings a langourous [sic] melody to their accompaniment. The middle portion of the movement is a somewhat grim scherzo; the final section a much modified restatement of the first. The third movement presents a theme which is an inversion of the original “germ” motive, over an impetuous, surging accompaniment. The composer’s Roman friends felt a distinct American Indian influence in this section, but he maintained that it reminded him more of some of the primitive fragments of melody he had heard sung in the Trastevere. After a quieter section, and a development, the music rushes headlong to a turbulent conclusion.

The Trastevere is residential district of Rome across the Tiber, picturesque in architecture, language, cuisine, and music — an “Old Rome” neighborhood.

A year would pass before the premiere but it was an auspicious one, in Rome by the Pro Arte Quartet of Brussels. Back in the U.S., the Gordon Quartet played the American premiere in Chicago and then toured with it to New York and Boston. The Boston Transcript critic picked up on the fox-trot aspect right away in an October 10, 1927 review titled “Chicagoan and Good”:

There is a “blue” theme, almost a “blue” tune in the first division of Mr. Sowerby’s String Quartet. There is also the rhythm of the fox-trot, occasional hints of the usage to which stringed instruments are subjected in a jazz orchestra. The “blue” matter returns in the finale… along with the rhythm and the hints. All this, flavorsome as it is, is relatively incidental. Rather, Mr. Sowerby has sought to make music out of his own head and to impregnate it, out of himself and his world, with a veritable and audible American spirit. We Americans answer to rhythm; we syncopate not only in the night clubs… but also in many a relation of life. We are a nervous, changeful, and hectic people “speeding up” even in our moods. Hence, Mr. Sowerby’s ejaculatory first movement and the pelter and the rush of his finale. We also sit in the sun; if we are artistically, poetically, or sentimentally minded, dream dreams and see visions — then shake ourselves into reality and go striding away. Therefore, Mr. Sowerby’s middle movement, warm, musing, then of a sudden “snapping out of it.” Designedly, his Quartet is abrupt, fitful, even short-breathed; but it has clear musical substance. The workmanship is modern, yet falls into none of the formulas of “modernism.” All of which… is to write a “truly” American music.

The author of over 50 articles and papers on the lives and music of Leo Sowerby and Sergei Rachmaninoff, Francis Crociata has served as president of the Leo Sowerby Foundation since 1993.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Recorded

Synconata and “Monotony” January 9 and 10, 2020, Kennedy-King College, Chicago, IL

Tramping Tune, Serenade, and String Quartet January 23 and 24, 2021, Boutell Memorial Concert Hall at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL

Cover Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra, Portrait, 1920’s

Photo JT Vintage/ glasshouseimages.com

Graphic Design Bark Design

Publishers

Synconata ©1993 Leo Sowerby Foundation

String Quartet in D minor ©1996 Leo Sowerby Foundation

Tramping Tune for Piano and Strings ©1994 Leo Sowerby Foundation

“Monotony” ©1993 Leo Sowerby Foundation

CEDILLE RECORDS © 2021

CDR 90000 205