Store

Store

Leo Sowerby: Symphony No. 2 & Other Works

Leo Sowerby, Paul Freeman, Chicago Sinfonietta, Czech National Symphony Orchestra

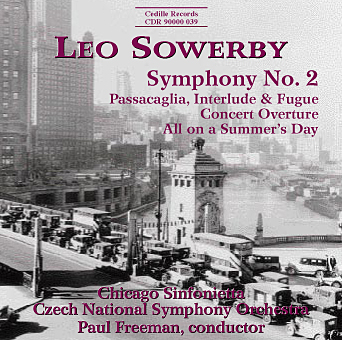

The roaring ’20s cover photo for Cedille Records’ disc of American composer Leo Sowerby’s symphonic music shows bumper-to-bumper traffic heading south on Michigan Avenue in the direction of Orchestra Hall, home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. If any of those motorists in their now-classic cars were headed to a symphony concert, the odds are high they would hear something by Sowerby (1895-1968).

This CD aims to restore Sowerby’s stature as a symphonist who “can be rated favorably with . . . his exact contemporary Howard Hanson and the younger Samuel Barber” (Fanfare). Paul Freeman conducts both of “his” orchestras, the Chicago Sinfonietta and Czech National Symphony Orchestra, in world premiere recordings of Sowerby’s Concert Overture; Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue; and Symphony No. 2 in B. Also on the disc is the jazz-ifused program overture All On a Summer’s Day (1954), commissioned and first recorded by the Louisville Orchestra and conductor Robert Whitney (a former Sowerby student). The music is presented in concert format, with each “half” containing an overture followed by a larger work.

The Second Symphony (1927-28), Sowerby’s most popular, “is vintage Sowerby”, writes Francis Crociata of the Leo Sowerby Foundation, citing its “brilliant orchestration . . . a heart-on-sleeve inner movement with its memorable horn solo, and explicit and virtuosic use of counterpoint culminating in a grand orchestral fugue.”

Sowerby originally composed Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue for solo piano. Following the success of his Second Symphony in Chicago and tone poem Prairie in Detroit, Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Chicago, he orchestrated Passacaglia for Frederick Stock of the Chicago Symphony. Sowerby wrote, “While the classic design of the Passacaglia has been adhered to rather strictly, the entire conception of the music is unacademic, and if anything, romantic.”

Little is known about Sowerby’s Concert Overture (1941), which bears a kinship to the music of William Walton, a friend of Sowerby’s since 1927. According to Crociata, “Walton’s spare, swift, and humorous orchestral writing was very much in Sowerby’s ear and consciousness” at the time.

All on a Summer’s Day (1954) was one of the earliest of the Louisville Orchestra’s celebrated series of contemporary music commissions. “My desire,” Sowerby wrote, “was to express and carry over to those who listen the sense of joy which June brings – a joy sometimes happily carefree, sometimes marked by a touch of wistfulness – and which I experienced at the time of its making.”

Once a precocious twenty-something composer as comfortable writing for Paul Whiteman’s band as for the Chicago Symphony, Sowerby was later dismissed as passé by much of the post-World War II musical establishment and its academic theorists, becoming pigeonholed as an organ and choral composer, albeit a stellar one. (In all, he composed 550 works for every medium except opera.)

Cedille’s restoration of Sowerby the symphonist began with its 1997 release, Prairie: Tone Poems by Leo Sowerby, with maestro Freeman and his Czech orchestra. That disc, brimming with what Fanfare called “the glories of Sowerby’s orchestral cosmos,” was deemed “one of the most important contributions to American discography in recent years . . . Not to be missed!”

Preview Excerpts

LEO SOWERBY (1895-1968)

Symphony No. 2

Artists

5: John Fairfield, solo horn

Program Notes

View Album BookletLeo Sowerby: The Crcuial Piece of The Puzzle at Last

Notes by Francis Crociata

“Some philanthropist should buy up every Sowerby record in the world, smash them all, destroy them, burn all the scores, obliterate the name of Sowerby from the face of the earth.”

— Alan Starr in Jane Langton’s

Divine Inspiration

The composer of 550 works for every medium except opera, Leo Sowerby (1895-1968) received his fair share of negative reviews. In 1921, subscribers of the San Francisco Symphony protested the “dissonant modernism” of A Set of Four—Ironics for Orchestra. By the 1940s, critics tended to dismiss Sowerby as a hopeless romantic reactionary. As late as 1963, New York Times critic, Harold C. Schonberg, reported the flight of several handfuls of mostly elderly patrons attending the Philadelphia Orchestra’s first visit to Lincoln Center’s “Philharmonic Hall” as if “pursued by the assembled hordes of Berg, Webern, Schoenberg, middle-period Bartok, accompanied by the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.” The bemused Schonberg returned to the incident in a charming Sunday meditation entitled “A Portion of Fryed Snake.” The refugees, he posed, had reacted not to the music (Sowerby’s Organ Concerto in C, “a thoroughly romantic affair — with cadenzas and everything”), but to the appearance of Leo’s unfamiliar name, much like the 18th century Jesuit who observed that he might have enjoyed his “portion of fryed snake” had he not been told it was snake.

However, the most malevolent notice Sowerby actually received never quite surpassed the fictional one put in the mind of the protagonist of Divine Inspiration, the 1993 novel by Jane Langton (©1993 Jane Langton, publ. Viking/Penguin) in her elegant “Homer Kelly” detective series. The Kelly stories deal with artistic and literary premises, this one the world of concert organists and organ builders. And for her purpose, Langton could not have chosen a more appropriate irritant: the voice on tape of the suspected murderer is inaudible due to the “background noise” of an organ recording — playing Sowerby! Her organists and builders were the organ world’s equivalent of the “original instruments” movement. Leo Sowerby, both in his music and the romantic-era “symphonic pipe organs” he wrote for, embodied the” excesses” they set out to reform.

Even as late as 1993, it would not have required an excessively wealthy philanthropist to work Langton’s hero’s wish; nor would “every Sowerby record in the world” have made much of a bonfire. But Ms. Langton was right on one count: Sowerby’s published music and recordings would have comprised mainly organ literature. Only an organist would have been in a position to make an informed judgment, intemperate or otherwise, about Leo Sowerby. Anyone venturing an opinion of his symphonic, instrumental, and song literature would have, of necessity, formed a judgment based upon the scantiest possible evidence: a single performance of a single work, hearsay or, worst of all, exposure to the most widely available recording of Sowerby’s orchestral music. This contained the tone poems Prairie and From the Northland, in a 1953 sight-reading by the Vienna Symphony and an acoustic atmosphere redolent of a cardboard box.

The appearance of this disc changes everything. The release of Leo Sowerby: Symphony No. 2, on May 1, 1998 — Sowerby’s 102nd birthday — together with the release last year of its companion disc, Prairie: Tone Poems by Leo Sowerby, offers the first opportunity to survey a broad and representative portion of Sowerby’s orchestral repertory.

Thanks to a committed, capable, and sympathetic musician, conductor Paul Freeman (who includes Sowerby champion Howard Hanson among his early mentors), and a skilled and enterprising record producer, James Ginsburg (whose label, Cedille Records, concentrates on the estimable contributions of Chicago’s musical voices), one can hear the first recording of any of Sowerby’s five orchestral symphonies in the context of a thoughtfully chosen cross-section of some of Sowerby’s strongest works spanning the years 1916 to 1954.

Less than ten percent of Sowerby’s secular music is as yet recorded. Nevertheless, it can no longer be said that there is insufficient information from which to form a judgment about his music. For the first time since the mid-1940s, Sowerby’s music can be accessed on something approaching equal footing with the most prominent of his contemporaries — be they “friends” like Hanson, Creston, Gershwin, Diamond, and Barber, or figures less sympathetic to Sowerby, such as Copland and Thomson.

I have been continually amazed by the extreme reactions evoked by the mere mention of the name, “Leo Sowerby.” Few Sowerby performances I have attended over the past thirty years have failed to make a positive connection with the audience (so rare — four out of several hundred — that I recall each vividly). Yet more often than not, the eyes of conductors I have approached seem to glaze over at the mention of his name. Did it evoke an unpleasant aural memory, perhaps the turgid LP recording of that ephemeral masterpiece of “Midwestern impressionism, “Prairie? Sir Georg Solti’s single Sowerby effort: Comes Autumn Time played in the manner of The Ride of the Valkyries? An overmatched choir or organist attempting one of the big anthems or cantatas?

Even those naturally attracted to the Sowerby repertory — usually through the organ works or one or another of the anthems — can be dismissive of the symphonic and chamber works. For years I quarreled with a great organist and teacher, Indiana University’s Robert Rayfield, who dismissed Sowerby’s secular music. A former Sowerby student, he has always been a wonderful and persuasive Sowerby interpreter. When we finally met, I learned that the reason for his rejection was simple: Rayfield knew only the organ works! The symphonic music was unplayed, the instrumental works unpublished. “Leo never mentioned them. I just assumed Leo wanted it that way.”

A more provocative example is the composer and diarist Ned Rorem. In his early diaries, Rorem barely mentions the first notable figure to treat his creative gifts with understanding and respect: his theory teacher at Chicago’s American Conservatory. Until recently, Rorem’s only relevant entry was a note from the day of Sowerby’s death, July 7, 1968, that Sowerby was the first estimable figure to take him seriously as a composer. Sowerby as a figure comparable in stature to Rorem’s vividly-drawn mentors, Virgil Thomson and Aaron Copland, had yet to appear.

Since 1980, memories of his early teacher have figured more prominently in Rorem’s meditations, with the fullest treatment to date appearing in his recent book Knowing When to Stop (©1994 Ned Rorem; publ. Simon & Schuster). Rorem’s first impression of Sowerby, dating from 1938, can hardly be improved upon:

Leo Sowerby was, with John Alden Carpenter, the most distinguished composer of the Middle West . . . Of my parents’ generation, a bachelor, reddished complexioned . . . and milky skinned, chain smoker of Fatima cigarettes, unglamorous and nonmysterious, likable with a perpetual worried frown, overweight and wearing rimless glasses, earthy, practical, interested in others even when they were talentless, a stickler for basic training. Sowerby was the first composer I ever knew and the last thing a composer was supposed to resemble. He was a friendly pedagogue.

Sowerby’s music was another story, clouded and mysterious in Rorem’s recollection. Rorem mentions regular attendance at Chicago Symphony concerts at the end of Frederick Stock’s long reign as conductor. Stock’s commitment to American music was as significant as that of the legendary “champions of American music,” Koussevitsky and Stokowski; and Sowerby was, by far, the American composer Stock loved best and played most. The young Ned Rorem’s musical consciousness was formed in the final years of the quarter-century Stock/Sowerby partnership, during which Sowerby was the Chicago Symphony’s de facto composer-in-residence. Yet Rorem’s early impressions of Sowerby’s music seem to evoke the prevailing wisdom of the years following Stock’s (and Koussevitsky’s) death, when one might have thought a malevolent philanthropist had, indeed, intentionally set out to “obliterate the name of Sowerby from the face of the earth” (and — excepting the organ works, anthems, and Comes Autumn Time — nearly succeeded). Nevertheless, I can hardly quarrel with the recollection Rorem does offer:

As to Leo’s music, I was shy of it. That he served as organist and choirmaster of Saint James’ Church on Rush Street (between two gay bars, though he wouldn’t have known), and excelled in sacred music, was stuffy and off-putting. Not until 1943, when I heard Paul Callaway in Washington play the haunting and sinuous Arioso for organ solo . . . and a few years later the cantata on texts of St. Francis, did I realize there was more to Sowerby than academic facility.

That observation is especially prescient in light of Sowerby’s own revelatory description of Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue (to follow). Later, while recalling the Cantata for which Sowerby received the 1946 Pulitzer Prize, Rorem gets to the nub of Sowerby’s obscurity and, perhaps, his own thirty-year silence on the subject:

Leo Sowerby came through town to hear . . . the world premiere of the Canticle of the Sun. He had been to Manhattan twice before, introducing me to . . . the specialized field of organ and church music, but never hobnobbing with the more cosmopolitan milieu, i.e., Aaron and Virgil. Instead, Leo seemed aloof to that he would name modish, the very milieu I longed to be accepted by, and which today would be called the Power Elite. Leo had met these ‘powers’ on committees, but they were as little aware of him as he them. If when Canticle of the Sun won the Pulitzer that spring of 1946 he felt vindicated, he didn’t let on. Vindicated of what?

Rorem did not know, and his modest teacher would certainly not have told him, about Sowerby’s Manhattan “hobnobbing” in the 20s and 30s — with George Gershwin, a colleague from the Paul Whiteman Orchestra jazz experiments; with Percy Grainger, who “mentored” Sowerby toward his twin passions of folk music and the English iconoclast Frederick Delius; and with Eugene Ormandy, whose own Carnegie Hall Philadelphia Orchestra debut in 1933 included Prairie and saw its composer the object of a flattering Time Magazine profile.

Rorem probably endows his teacher with more self-effacement and self-assurance than is justified. A few more years would pass before a stark reality became very evident: his secular music was disappearing from concert halls. But even in 1946, Sowerby could not have ignored the fact that his orchestral and chamber music had never received the kind of “fair hearing” in New York that he had enjoyed for so long in Boston, Philadelphia and, especially, Chicago. Copland and Thomson, both of whom dismissed Sowerby in print with the faintest possible of praise, didn’t have to go out of their way to do so. No Sowerby symphony has ever been heard in a New York concert hall. Nor did any of Koussevitsky’s Sowerby performances occur at Tanglewood, where Copland, Thomson, and others of the “Power Elite” would likely have been present to hear it. Stock’s Chicago Symphony was broadcast seldom, recorded little, and visited New York (seat of the Power Elite) hardly at all.

We do not know if Sowerby was aware that the Pulitzer jury in 1946 comprised his friend Howard Hanson, the Columbia University factotum Chalmers Clifton, and . . . Aaron Copland. Nor could he have known that the only other serious figure under consideration for the 1946 Pulitzer was, in fact, Virgil Thomson. We do know that Sowerby was savvy enough to recognize the pigeon-hole (“Dean of American Church Musicians”) fast enclosing him. Stock died in 1942. The few Chicago Symphony performance of the 1940s were initiated by prominent soloists: organist E. Power Biggs (“Classic” Concerto) and violist William Primrose (Poem for Viola and Orchestra). Koussevitsky retired in 1946, though he would give one more Sowerby premiere, the Fourth Symphony on January 11, 1949. Koussevitsky also promised a New York performance, but died before it materialized, leaving his Boston performance of the Fourth the last Sowerby symphony to be heard anywhere until 1989. After 1946, most major performances and broadcasts of Sowerby’s concert music were of the concertos commissioned by the faithful Biggs, which only reinforced the composer’s organ-choral stereotyping. Is it any wonder that, to the end of his life, Sowerby vainly insisted Canticle was a secular (i.e. “concert”) work?

Notwithstanding the marginalization of Sowerby on concert stages, the composer remained prolific and varied to the end of his life. His monumental Piano Trio in B, many instrumental sonatas and suites, the still unperformed Symphony No. 5 and Organ Concerto No. 2, sublime settings of poems of John Donne (La Corona for Chorus and Orchestra) and Emily Dickinson (Five Songs) nestle quietly among the hundreds of published and frequently performed organ and choral works of his final three decades. Of the four works on this disc, only All On a Summer’s Day follows his Pulitzer recognition. All four tone poems on Maestro Freeman’s companion disc pre-date the Pulitzer. In fact, most of Sowerby’s known orchestral works date from the years of his remarkable collaboration with Frederick Stock. Dr. Freeman could not have selected two better “offspring” of that collaboration than the Second Symphony and Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue.

The Sowerby/Stock partnership began on January 16, 1916 with the unprecedented all-Sowerby concert at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall. Stock did not conduct. In fact, until then, he conducted little, if any, American music. The “Sowerby Concert” was organized by CSO associate conductor Eric DeLamarter. DeLamarter prevailed upon his boss to attend and, from that moment, Frederick Stock became committed to American music in general and a slight (5’4″), red-haired, 21-year-old prodigy in particular. No Mahler symphony, Strauss tone poem or Rachmaninoff concerto (Rachmaninoff played more often under Stock than any other conductor) — staples of the Stock repertory — received a more painstaking preparation or sympathetic interpretation than he lavished, year-after-year, upon the succession of symphonies, concertos, and tone poems brought up to Orchestra Hall from Sowerby’s Hyde Park apartment (or “down” from the choirmaster’s study at St. James’).

SYMPHONY NO. 2 IN B, H.188 (1927-28)

Leo Sowerby composed five orchestral symphonies plus an, as yet, unperformed “Psalm Symphony” for the same forces (and of the same length) as Mahler’s “Symphony of a Thousand.” He also composed two symphonies for solo organ: the widely known Symphony in G, and the late, unjustly neglected Symphonia Brevis.

Since this is the first recording of a Sowerby Symphony, a chronological context would be helpful.

No. 1 in E minor, H. 163 (1920-21) — premiered by Stock and the Chicago Symphony on April 7, 1922.

“Psalm Symphony,” H.175 (1923-24) — not as yet performed.

No. 2 in B minor, H.188 (1927-28) — premiered by Stock and the Chicago Symphony on March 29, 1929.

No. 3 in F-sharp minor, H.245 (1939-40) — written for the 50th Anniversary of the Chicago Symphony and dedicated to Dr. Frederick Stock and the Orchestra; premiered by them on March 6, 1941.

No. 4 in B, H.284 (1944) — premiered by Serge Koussevitsky and the Boston Symphony, January 7, 1949.

No. 5 in G, H.404 (1964) — requested by Eugene Ormandy, but apparently never seen by him and, in any event, not as yet performed.

Sowerby’s second orchestral symphony can be called his most “popular,” having been performed on a dozen occasions to date. It may well be his finest, but its currency may be as much due to its brevity and concision. It is “vintage Sowerby” with all of the composer’s hallmarks: brilliant orchestration (a virtual “concerto for orchestra,” specifically the Chicago Symphony Orchestra), a heart-on-sleeve inner movement with its memorable horn solo, and explicit and virtuosic use of counterpoint culminating in a grand orchestral fugue.

The first and second movements were composed in Chicago in March and April 1927, the fugue finale in November. The orchestration was completed during the spring of 1928. Much was happening in Sowerby’s life around this time. In September 1927, he began his tenure as organist-choirmaster of St. James’ Episcopal Cathedral. He was busy as an organ soloist thanks to the popularity of his Medieval Poem for organ and orchestra (a Stock favorite). He was also finishing his most popular tone poem, the Carl Sandburg-inspired Prairie, and beginning his masterpiece, Symphony in G for solo organ — whose publication by Oxford University Press and dozen recordings (the first by E. Power Biggs for RCA in 1941) would assure his “immortality.”

The composer provided these notes for the Symphony:

The first movement (Sonatina) is in B minor. The principal subject (in alternating 3-8 and 2-4 time) begins at the third measure in the woodwinds . . . heard in a variety of forms, and comes to an abrupt conclusion some ninety measures later. A very short bridge passage follows [leading] to the second theme, given to the oboe and accompanied by divided strings. The Development is concerned almost entirely with the two principal subjects, and commences in 5-4 time with a fragment of the first theme in the bass and a fragment of the second in the upper voices. At the conclusion of the Development a climax is attained and the Recapitulation sets in, fortissimo. This Recapitulation differs materially from the Exposition, the bridge passage having been lengthened and the second theme omitted altogether. The movement ends solemnly with the principal subject in augmentation.

The Recitative opens with a passage in 4-4 time for a solo horn, really the principal theme . . . answered nine measures later by muted and divided strings. Again the horn takes the theme, and once more the strings reply. There is a duet on the same motive for the clarinet and English horn. The violins gradually assume a more important part . . . playing one of the motives in an unbroken succession of melody. After a climax has been reached there is general subsidence, and the duet is heard once more, this time between the flute and muted trumpet. The movement ends quietly, as it began, with the horn theme, accompanied by the kettle drum. The horn comes to rest on B flat while the drum obstinately sticks to C — the result being uncertainty as to whether the movement is in E-flat major or in F major . . .

A passage of rough woodwind chords (4-2 time) and a rough trumpet theme ushers in the final movement [Fugue]. The subject of the fugue is foreshadowed in this, but the fugue proper does not begin until the twenty-eighth measure. In the meantime the brass have built up a climax under an inverted pedal-point on B, held in the higher strings. This note B then becomes the first note of the fugue subject, which appears tranquilly in the first violins, divided in octaves. The second violins answer a fourth lower, the first violins continuing with the counter-subject. It may be said the fugue is strict, and all the devices of inversion, diminution, stretto etc., are used in due course and in the orthodox places . . . Toward the close there is a stretto in which the complete subject appears fifteen times. The music becomes more jubilant and the speed is increased. The conclusion is grandiose . . .

Stock introduced the Second Symphony on March 29 and 30, 1929. This was, in fact, Good Friday and Holy Saturday — about which the composer complained in a letter to his mother and sister: “[Mr. Stock] . . . certainly picked the worst time for me, on account of the terrific amount of work at the Church. . .” Reviews — both local notices and dispatches to the national musical press — were unanimously positive. Everyone singled out the fugue. Sowerby struggled with rousing endings: many of his most popular works — Prairie; Medieval Poem; Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue; and Canticle of the Sun — end quietly. That he succeeded here so decisively must have been especially gratifying, as critic Edward Moore’s Chicago Tribune notice attests: “. . . the third movement was a gorgeous fugue which was at the same time a stirring piece of music. The fact is worth recording because so may modern fugues have turned out to be just fugues. This one became music and was one reason why Mr. Sowerby’s presence was demanded on the platform after the performance was over.”

Moore also raised the issue of the numbering of Sowerby’s Symphonies. Although announced in the program as the second, Moore correctly identified it as the third, noting that Sowerby’s grandest work, “Psalm Symphony” for chorus, orchestra and organ, composed during his Rome Prize fellowship, is actually the composer’s unnumbered second orchestral symphony.

PASSACAGLIA, INTERLUDE AND FUGUE, H. 207 (1931-32)

Much has been made of the fact that Leo Sowerby composed the first orchestral passacaglia by an American. In an interview a year before the first performance, Sowerby credited Paul Hindemith, his only contemporary to make a contribution in the form and a figure for whom Sowerby had a growing admiration. Hindemith reciprocated and delighted in repeating Oscar Sonneck’s complement: “the Three B’s of music — Bach, Beethoven and ‘SowerB.'”

In the Passacaglia (and the related Chaconne form) Sowerby found his favorite, most comfortable, and most successful form of expression. His 1930 Organ Symphony in G concludes with a memorable passacaglia. After it, Sowerby immediately turned to this passacaglia, originally as a work for piano solo. (It is, in fact, an attractive and effective work in that form.) Then — hard on the heels of the success of the Second Symphony in Chicago, and Prairie in Detroit, Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Chicago — he orchestrated it for Stock. There followed the only unpleasant moment in their relationship. Stock announced the work’s world premiere for the last concerts of the 1932-33 season. Sowerby had already received a prominent CSO performance that season, the Ballade for Two Pianos and Orchestra (“King Estmere”), and Stock was being pressured by his financially beleaguered board and management to “stick to the classics.” Stock was embarrassed. Due to the publicity the work had already received because of the novelty of the form, Sowerby was also embarrassed, but the work was withdrawn two weeks before the concert.

Stock made good on his promise on February 22, 1934 and successfully revived the work in 1937. When Fritz Reiner (who gave the American premiere of From the Northland with the Cincinnati Symphony in 1923) began his Chicago tenure in 1953, he took up Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue and performed it during the 54-55, 57-58, and 61-62 CSO seasons. On each occasion, the CSO published this note by the composer:

The Passacaglia (F sharp minor, 3-4 time) presents twenty-three variations on a six bar theme. A connected passage of five bars for flute and bassoon in octaves leads to the Interlude (A major, 6-4 time), which presents melodic phrases for the [woodwinds]. The thematic material is derived from the Passacaglia theme.

The Interlude, which is but twenty-four bars long, ends very quietly in the lower strings and the Fugue (F sharp minor, 4-4 time) commences without pause. The subject of the Fugue . . . closely related to the Passacaglia . . . pursues a course of development proper to the form and rises to its principal climax just as the stretto commences. From this point it subsides to the close through a gradual ritardando and ends tranquilly.

It may be added that while the classic design of the Passacaglia has been adhered to rather strictly, the entire conception of the music is unacademic, and if anything, romantic. [emphasis mine — FC]

CONCERT OVERTURE, H.251 (1941)

Virtually all of Sowerby’s orchestral works from before 1945 were commissioned, or at least requested, by either a prominent orchestra (Boston or Chicago) or soloist (Biggs, Alfred Wallenstein, Jacques Gordon). Concert Overture is the first exception, and we know very little about it. It was published immediately, but not played in Chicago or by any other major orchestra. (The CSO added it to its Sowerby repertory for Orchestra’s 100th Anniversary season in 1991.) The first known performance occurred on Oct. 19, 1942 by the New Haven Symphony under Hugo Korschak, though that program does not claim a “world premiere.” There is not a single mention of the work in Sowerby’s correspondence.

I find in this work a kinship to the music of William Walton — a friend of Sowerby’s since 1927. In his capacity as Stock’s “composer-in-residence,” Sowerby naturally provided the principle commissioned work for the CSO’s 1940-41 50th anniversary season: his Third Symphony. Sowerby also advised Stock on other anniversary commissions. The most significant of these was, arguably, Walton’s comedy-overture, Scapino. Walton’s spare, swift, and humorous orchestral writing was very much in Sowerby’s ear and consciousness during the writing of Concert Overture. Unfortunately, the publisher did not challenge Sowerby to provide a more colorful or descriptive title as his organ publisher, H.W. Gray, did in the case of a previous “Concert Overture” for organ, rechristened for publication as Pageant of Autumn.

ALL ON A SUMMER’S DAY, H.325 (1954)

When Stock fulfilled his promise to play Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue in 1934, the very next concert included a work by the composer Robert Whitney, then a student of Sowerby’s at the American Conservatory. Whitney would become conductor of the Louisville Orchestra and creator of its singular program of contemporary orchestral commissions and recordings. One of the earliest “Louisville Commissions” was for this jazz-infused program overture, introduced by Whitney on January 8, 1955 and subsequently recorded. Sowerby provided these comments for the first performance:

This work was sketched in June, 1954, and scored in August. In writing it my desire was to express and to carry over to those who listen the sense of the joy which June brings — a joy sometimes happily carefree, sometimes marked by a touch of wistfulness — and which I experienced at the time of its making. So many art manifestations of our time are studded with problems or seem to be demonstrations of theories, there is much anxiety and gloom expressed in today’s music — and I myself have to answer for my share of it. This time, however, I felt the urge to put these things to one side and to write music which should mirror the sunny moods of exhilaration most of us experience “all on a summer’s day.”

In addition to the attributed quotations, I have drawn upon the writings and recollections of and collaborative work with my late friend and colleague, the great Sowerby scholar, Ronald M. Huntington (1931-1994). He is the “H” in the chronological catalogue of Sowerby’s music.

Francis Crociata is President of The Leo Sowerby Foundation.

Album Details

Total Time: 60:51

Recorded: Oct. 21-24, 1996, studios of Czech National Radio, Prague and April 2, 1997 at Trinity Hight School, River Forest, Illinois.

Producers: James Ginsburg & Burke Morton

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Production Assistants: Francis Crociata and David Dieckmann

Cover: Michigan Avenue Bridge, Chicago, 1929; photo © Chicago Historical Society ICHi-23634

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Francis Crociata

© 1998 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 039