Store

Store

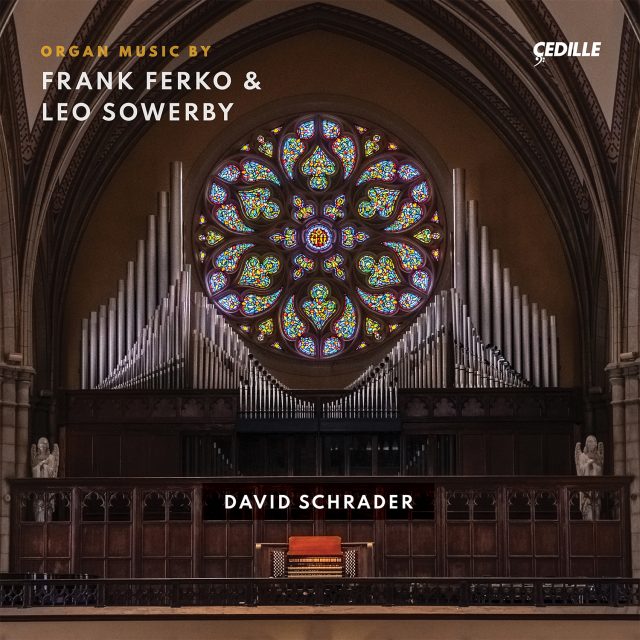

Organ Music By Frank Ferko & Leo Sowerby

Versatile keyboard virtuoso David Schrader, heard on more than two dozen Cedille Records albums, performs attractive 20th- and 21st-century solo organ works by Frank Ferko (b. 1950) and Leo Sowerby (1895–1968), prolific composers known for their organ mastery and closely associated with the city of Chicago.

Ferko’s works, all world-premiere recordings, are heard on three different mechanical-action organs at The House of Hope Presbyterian Church, St. Paul, Minnesota. The intimate Music for Elizabeth Chapel is performed on the organ it was written for: the 19-rank Jaeckel, Opus 41. Variations on a Hungarian Folk Theme, also written for the textures and colors of a small instrument, is heard on an authentic Romantic-era French organ, with 13 ranks, built by Joseph Merklin in 1878 for a church in southern France.

Ferko compositions performed on the 97-rank C.B. Fisk Opus 78 (1979) include Variations on “Veni Creator Spiritus,” based on a ninth-century plainsong hymn; Angels — Chaconne for Organ, Missa O Ecclesia: Communion, and Mass for Dedication, all based on chants by 12th-century abbess, composer, and Christian mystic Hildegard von Bingen; Symphonie brève, dedicated to Schrader; and Tired Old Nun, a novelty piece scored for pedals alone, with waltz, slow blues, and boogie variations.

Schrader offers his Sowerby program on the 68-rank Wicks Opus 2918 organ at St. Ita’s Catholic Church, Chicago, renovated in 2003 by H.A. Howell. Like the great Skinner organs that Sowerby knew well, it includes a Solo division with stops that are essential to performing the composer’s large-scale works. Repertoire includes some of Sowerby’s best-known organ music: the brilliant program overture Comes Autumn Time; the virtuosic Pageant, championed by Virgil Fox; Toccata, a recital staple for generations of American organists; and the monumental Symphony in G Major, first recorded in 1942 by British organist E. Power Biggs for RCA Victor. Schrader also includes a Sowerby rarity, the March from Suite for Organ.

The world-premiere recording of a late Sowerby work, Two Sketches, is included as a bonus on digital editions of the album.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with David Schrader on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

FRANK FERKO (b. 1950)

Music for Elizabeth Chapel

Symphonie brève

Mass for Dedication

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletOrgan Music By Frank Ferko & Leo Sowerby

Notes by Frank Ferko and Francis Crociata

My works presented on this recording were all composed, first performed, and published between 1987 and 2005. Most of the pieces are in the form of theme and variations, but other forms and genres are represented as well. In a few cases the pieces were commissioned specifically for dedication recitals of new or renovated instruments, and thus, they were designed to showcase the specific tonal colors of the organs for which they were written. The three mechanical-action organs at The House of Hope Presbyterian Church in St. Paul, Minnesota provided a variety of organ design and tonal palette that is well suited for these pieces, so I am delighted that these works were recorded on those instruments.

Music for Elizabeth Chapel

Commissioned by Mark and Audrey Schindler, Music for Elizabeth Chapel was written for the 2002 dedication concert of the 19-rank Jaeckel organ, Opus 41 (2001) in Elizabeth Chapel at The House of Hope Presbyterian Church. The work is in three movements, each based on a different hymn melody, each selected by the Schindlers.

I. Leoni: Chorale Variations (chorale with 6 variations)

II. St. Elizabeth (Crusader’s Hymn): Chorale Variations

(chorale with 6 variations)

III. St. Anne: Toccata and Fugue

Because the entire work was composed for a small organ, specifically, the Jaeckel instrument in Elizabeth Chapel, much of it makes use of various types of counterpoint, both imitative and non-imitative. The individual variations have been conceived in different styles, including the 18th century musette and chorale prelude, a contrary motion canon in trio style, a waltz, and even one variation played entirely by the feet on the organ pedals. The Toccata on “St. Anne” is written in a minimalist style with the hymn tune appearing in the pedals on a high pitched (4’) solo stop;

the fugue incorporates an eclectic mix of styles to continue the idea of “variation.”

Variations on “Veni Creator Spiritus”

The basis of this work is the plainsong hymn, Veni Creator Spiritus, attributed to Rabanus Maurus Magentius, a ninth-century Frankish Benedictine monk, theologian, author, and poet. The work was commissioned by St. Chrysostom’s Episcopal Church in Chicago for one of the dedicatory concerts for its 33-rank C.B. Fisk organ in 2005. Designed to showcase the organ’s variety of tonal colors, the individual variations were created to feature specific stops and stop combinations available on that instrument. As with all but one piece on the rest of the album, it is played here on C.B. Fisk’s Opus 78, installed in 1979.

Musically, the variations employ harmonies derived from standard major and minor scales as well as the octatonic scale, and they range in texture from small clusters (theme) to sparse octaves (variation III), two-voice “commentaries” (variations I and V), melody and accompaniment in three totally different styles (variations VI, VII, and VIII), accompanied canon at the interval of the fourth (variation IV), and a toccata with full organ (variation IX). Variation III was composed in two versions: manuals only (no pedals), and manuals with pedals. The latter version, with pedals, is the version presented on this recording.

Angels: Chaconne for Organ

Although the traditional chaconne form is a set of variations performed over a repeating musical pattern in the bass

line (also called a “ground” bass), this chaconne is based on a repeating harmonic pattern played on one of the organ manuals. The pattern is a harmonization of the first phrase of the chant, O aeterna Deus, composed in the 12th century by Hildegard von Bingen. Each variation is derived from the interval of the perfect octave or the perfect fifth to depict the perfection of the angels themselves. The perfect intervals manifest themselves in various ways, including expansions of the original harmonies in the fifth and sixth variations, and the rhythmic variation extends to a full-blown tango (sixth variation) to express the exuberant joy of the angels praising Almighty God.

Angels was commissioned for the dedication of the 25-rank Hellmuth Wolff organ at St. Giles Episcopal Church in Northbrook, Illinois and received its premiere on November 13, 1994.

Symphonie brève

This short symphonic work was composed for a concert performed by the composer at the Church of St. Paul and Redeemer in Chicago on October 4, 1987.

The first movement is based on the principle of the ground bass played on the pedals. Each repetition of the bass line is a slight variation of the original, however: as the music progresses, the bass line becomes shorter on each repetition. A contrasting central section continues the basic eighth-note rhythmic motion established in the first section but abandons the bass line to provide a harmonic commentary played on the manuals. The ground bass returns as a brief recapitulation of the first section, this time with a more aggressive shrinking process. The second movement, written in a very quiet minimalist style, is based on the plainsong “Alleluia” from the Mass for the Day of St. Francis, played on a solo 4’ stop. This movement was originally improvised at the 1987 concert and later transcribed for the publication of the score. A massive chorale, organized in A-B-A form and based on motives from the first movement, concludes the work.

David Schrader took a particular interest in this work shortly after it was composed, and he has performed it, either in whole or in part, on many occasions. With much gratitude, I dedicated Symphonie brève to David.

Missa O Ecclesia: Communion

In 1995, my publisher, Robert Schunemann, requested a short organ piece for publication, and the result was “Communion.” It was my intention to incorporate this movement into a complete organ mass, but as it turned out, I never wrote the remaining movements. Based on the opening of the chant, O Ecclesia by Hildegard von Bingen, the piece is a very quiet meditation featuring some of the milder tonal colors of the organ. It is, thus, quite suitable for performance on small instruments.

Variations on a Hungarian Folk Tune

Composed in 1994, this work consists of a theme and six variations. It was originally conceived as a teaching piece to be played on a small organ, but it has often been performed as a concert work. The various treatments of the theme include bicinium (theme and variation IV), two-voice canon (variation II), inversion (variation III), and a tango (variation VI). As in Music for Elizabeth Chapel, also written for a small organ, this work presents a variety of textures, each requiring distinctive tonal colors of the organ. This is the one piece on the album performed on the church’s 13 rank, two-manual, 1878 Joseph Merklin organ, restored by C.B. Fisk and installed in 1987.

Tired Old Nun

Tired Old Nun dates from 1996 and was written as a birthday gift for Chicago organist Richard Sobak. As the title suggests, the work is a novelty piece, and although it is based on the plainsong “Alleluia” from the Mass for the Day of St. Richardis, it is not intended for liturgical use. Consisting of a theme and six variations, the entire work is intended to be played on the organ pedals, that is, performed only with the organist’s feet. The various tonal colors required come not only from the pedal division of the organ but also from the coupling of manual stops to the pedals.

The musical styles represented in the variations include a waltz (variation II), slow blues (variation V), and boogie (variation VI).

Mass for Dedication

This five-movement work was commissioned for the 2002 dedication of the renovated 57-rank Howell organ at Christ Church in Winnetka, Illinois. It is organized in the standard organ mass format: (1) Entrance — (2) Offertory — (3) Consecration — (4) Communion — (5) Finale. Thematically, the work is based on three fragments of the 12th century chant O orzchis Ecclesia by Hildegard von Bingen, and these fragments can be heard in their original and varied forms throughout the piece. Since the chant was originally written to be sung at a time of dedication, it was appropriate to use this particular chant as the basis of this work.

“Dr. Sowerby, is it true that you’ve written a piece you can’t play yourself?”

The name of the American Conservatory student whose question challenged the Chicago music school’s most famous graduate and faculty member is now long forgotten, as is whether the piece in question was the pedal tour de force, Pageant, or the treacherous middle movement, “Fast and sinister,” from the Symphony in G major. But either work neatly fits the legend and the punchline, no doubt delivered with his trademark mock-serious huffy deadpan delivery as retold by generations of his students: “I don’t know if I can or not… and I don’t intend to find out!”

Pageant and the Organ Symphony date from the very heart of Leo Sowerby’s “Golden Age.” In the early 1930s, his astonishingly inventive lyric gift, technical mastery of the elements of musical form, and virtuoso keyboard performance led him to be, for several years, the most frequently performed American composer of symphonic music and, for the remainder of his life, the most frequently performed American composer of choral and organ music. The Organ Symphony and Pageant conquered the concert organ world at almost exactly the same moment that a performance of his tone poem, Prairie, resulted in a feature profile in Time Magazine.

Sowerby once told his former student, Robert Rayfield, that he divided his 92 organ compositions into three periods, and David Schrader has selected works from all three: “Orchestral” (1913–1926), in which he thought of the organ in orchestral terms; “Pure Organ” (1927–1937), in which he wrote more idiomatically, placing less emphasis on tone colors; and “Baroque Response” (1937–1968), during which his writing became more linear.

Four of the five works that Mr. Schrader selected for this CD would surely number among Sowerby’s dozen or so “greatest hits.” Indeed, the Organ Symphony has received more than a dozen commercial recordings on CD, LP, and, beginning with E. Power Biggs’ landmark 1942 Victor recording on 78 RPM shellac discs. I am especially grateful that Mr. Schrader includes the rarely performed March from Suite for Organ and, as digital tracks separate from the physical album, the even more rarely performed late work, Two Sketches, one of which (“Nostalgic”) extends the Sowerby style into the realm of serial techniques, at least for about four minutes.

Comes Autumn Time H 124a (1916)

Eric DeLamarter (1880–1953) is an obscure figure in 20th-century American music, even in Chicago, which was home for much of his life. He was a prolific and much-performed composer, conductor, church musician, and critic. Yet if he is remembered at all today, it is mainly as a footnote to the anti-German current that swept several prominent German maestros, including Chicago’s Frederick Stock, off their podiums during World War I, leaving DeLamarter, briefly, chief conductor of the Chicago Symphony. He is also remembered by Sowerby fans for announcing in the Chicago Tribune in 1916 that he would be playing the world premiere of “From the Southland” by Leo Sowerby on the following Thursday at Fourth Presbyterian Church.

DeLamarter pulled the title, and indeed the piece, out of thin air, as he had neglected to mention the “commission” to his young assistant. Inspired by verses of Canadian poet Bliss Carmen (1861–1929), Sowerby completed in a single afternoon the brilliant program overture that numbers among dozen or so of his 550 compositions for which he is best known today, both as a staple of the organ recital repertory (Marcel Dupré played its Paris premiere) and in its orchestration, also premiered by DeLamarter. The latter was also conducted by Stokowski, Koussevitzky, Walter, Reiner, Hanson, Rostropovich, Solti and, in his magisterial Cedille Records survey of Sowerby orchestral works, the late Paul Freeman.

In his 1933 The Diapason survey of Sowerby’s organ works, Albert Riemenschneider (1878–1950) drew a connection between the interplay of the overture’s two main themes and the autumnal season the composer portrays: “…one can class this composition as a sonata, which, in the recapitulation, presents the second subject first in order…. After presentation of the first theme there follows a coda… a brilliant and dissonant ascending passage as if to suggest the closing in a burst of autumnal glory.”

Pageant H 205 (1931)

One doesn’t expect flamboyant technical display to be the most prominent feature of a Sowerby organ work, although formidable technical challenges abound throughout Sowerby’s organ repertory. Pageant is the exception to the rule, intentionally so, for it was commissioned by the young firebrand virtuoso Fernando Germani (1906–1998), famous for his service as first organist at the Vatican from 1948 to 1959, during the papacy of Pius XII. During his Rome Prize fellowship (1921–1924), Sowerby met Germani, then organist of Rome’s Augusteo orchestra. In 1926, Germani played his first American tour, the centerpiece of which was Sowerby’s Mediaeval Poem for Organ and Orchestra, including performances in New York and Philadelphia conducted by the composer. He asked Sowerby to compose a work to spotlight his much admired pedal technique and, upon receiving Pageant, telegraphed one of music history’s great one-liners: “Now write me something really difficult!”

The piece is in the form of an introduction and variations on a martial theme, which one British critic called “the epitome of Yankee jingoism.” Riemschneider described the opening as “a clarion call to battle and the fight his on… As a means for maintaining both their mental and physical properties at their best condition of fitness this selection is highly recommended to those organists who are capable of mastering its difficulties. It was written as a challenge to the fleet-footed young Italian organist, and a challenge it will remain for any fleet-footed organist of the virtuoso type.” Riemschneider was probably thinking of Virgil Fox, who attended the American Conservatory and was among the first to ride Pageant to his early recital success. Ever since, it has become a rite of passage for young organists (much as the Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto has been for young pianists) and, in the age of cameras and projection screens, a visual treat for their audiences.

Toccata H 259 (1941)

In the pre-war year of 1941, Sowerby produced toccatas for piano and organ, both on requests from former students.

The piano work was commissioned for the Mercury Music series of publications by his composition student, Gail Kubik (who, like Sowerby, would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize). The Toccata in C for organ was chosen by conductor William Strickland to inaugurate a new H.W. Gray series of contemporary organ works that would eventually include works by, among others, Piston, Krenek, Sessions, Schonberg, Milhaud, and Copland.

Three-part in structure, the Toccata proceeds from a graceful, expansive arching modal theme over an intricate accompanying figure. Gradually, that accompaniment recedes preparing for the quieter, though no less intricate, middle section in which the main theme is broken into bits and pieces that dialog with one another until Sowerby gracefully draws them together for a final, grand triumphant statement in the pedals.

Sowerby obviously loved and took satisfaction in his Toccata, including it on every program he played for the rest of his years as a recitalist. This work has been a fixture in the repertories of countless American organists. Catharine Crozier (1914–2003) recorded the Toccata three times; it was also championed and recorded twice by Sowerby’s friend and colleague, the composer-organist of England’s York Minster Cathedral, Francis Jackson (b. 1917).

Suite for Organ H 222 (1934) IV. March

Two of Sowerby’s most frequently performed works are movements from the Suite for Organ, which he composed for Oxford University Press to follow on the great success Oxford enjoyed with the Symphony in G. The Suite’s March is not one of those perennial favorites. Those are the two middle movements, Air with Variations and Fantasy for Flute Stops. The opening Chorale and Fugue is, like the March, rarely encountered on recital programs.

Oxford published the four movements separately before gathering them in a single volume. The March may owe its obscurity to its being overshadowed by the two very popular movements that precede it in the Suite and also by confusion with another march published a decade before, A Joyous March (H 148). The Suite’s March couldn’t be more distinct from that earlier, straightforward, Grainger-like outpouring of post-war optimism. Like the Toccata,

it has an overall ternary structure, built around a rather urbane theme, by turns raucous, then insinuatingly sly, quietly melancholic, caustic, sarcastic, and finally boldly triumphant. Depending on the organist’s approach, it can strut or swing or meander. The composer told one of his students it was inspired by a painting by Rainey Bennett, as was the Suite’s Fantasy for Flute Stops. To a contemporary friend and colleague, Sowerby said the March reflected a variety of ceremonial marches and processions he’d experienced as a bandmaster and Anglican organist-choirmaster. That colleague, the organist-composer M. Searle Wright (1918–2004), also mentioned the composer’s request that he play the entire Suite, something he’d never had the opportunity to hear in a recital program before. Wright complied with this request by performing the full Suite on three separate American Guild of Organists recitals.

Symphony in G major H 206 (1930–1931)

I. Very broadly

II. Fast and sinister

III. Passacaglia

and life for over 50 years and long ago surrendered objectivity in appraising the composer’s place, and even the relative strengths of his immense 550-work oeuvre. I do feel safe, however, in suggesting that he left two incontestable masterpieces that will live as long as music lives: the Lenten cantata Forsaken of Man and the Symphony in G for organ.

Sowerby’s impetus for composing the Symphony in G was two-fold: one practical and one personal. From the practical standpoint, friendly professional acquaintances, including composer William Walton, gained Sowerby entry with the prestigious publisher Oxford University Press. Oxford wanted a new, large-scale composition to follow the success of the five-movement piano suite, Florida. From a personal standpoint, Sowerby wanted to write a major work for the organist he and the rest of the American organ community regarded as the one peer to the great French masters Vierne and Widor: Lynwood Farnam (1885–1930), founding chairman of the organ department at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.

Sowerby began his Organ Symphony with the finale, its Passacaglia, and indeed the Passacaglia had several public performances before the entire work — particularly the 20-minute opening movement with its five successively more passionate/exultant climaxes — was completed. Right from the beginning, the Symphony’s first movement was a challenge for organists and listeners alike, demanding attention to the complex unfolding of classical form in a emotion-laden romantic language that has as much in common with Mahler and Bruckner as with Bach, Franck, and Vierne. The scherzo/rondo and the passacaglia are much more easily accessible on first hearing, especially to modern ears, but the first movement reveals more of its beauty and power with repeated hearings.

Of the first movement, the composer wrote to his greatest champion, the British organist E. Power Biggs (1906–1977) before Biggs’ 1942 recording for RCA Victor:

The development is fairly long and complicated and concerns itself with material from both the first and second themes. A great climax is finally reached with the full organ… after which the recapitulation of the first theme is introduced (G major) considerably shortened. The second theme is now heard in G major (opening record side 4). The coda which concludes the movement is designed to unite the two principal themes… and to demonstrate that they are one theme, after all.

I don’t know who originated it, but the famous quip about the “Fast and sinister” second movement is that it is “fast for the audience and sinister for the organist.” I am grateful to Michael Barone, the estimable organ scholar and host of Public Radio’s PipeDreams, for the inciteful suggestion that the second movement’s opening dissonant dialogue of chords is evocative of car horns on Chicago’s Michigan Avenue at dusk — a sound that would have been very familiar to Sowerby, seated at his customary dinner table in the Cliff Dwellers Club atop Orchestra Hall. I’m fond of this rather tongue-in-cheek commentary from G.D. Cunningham, an English writer who performed the Symphony in 1938:

The second movement, marked “fast and sinister,” is in 5-4 time, and is very original. After some preliminary bars the first subject is announced on the pedals. It is very lively and energetic, and indeed the whole movement, in its unceasing rhythmic vitality, is a complete contrast to the previous one. It is in Rondo form and at each return of the subject the composer adds some new feature of interest for the listener, and (alas!) some fresh trials for the performer.

The last movement is a fine Passacaglia, full of clashing harmonies and consecutive fourths, fifths and sevenths. The whole symphony is extremely difficult, and there are several passages of double-pedaling with the feet at opposite extremes of the pedalboard. (I may add that this sort of thing is becoming so common that the anatomical risks which we organists run are too frightful to dwell upon!)

Sowerby wrote to Biggs:

The Symphony was composed in 1930 [Ed. — actually completed in 1931]; I don’t know the date of the first performance. Since it was published by the Oxford University Press in London, it was probably first played in England…. It is dedicated to my friend, Lynnwood Farnam, who is certainly the greatest organist I ever knew; it so happened that the Symphony was published after his death, but I wanted the dedication to stand nevertheless…. I might say that my Symphony has no “program” or no extra-musical significance or intent. It is as much a piece of architecture in sound as any of the works of the masters of the Baroque period, though I do not pretend to make any further comparisons.

To the composer’s remarks I add these concluding lines from Albert Riemenschneider’s study of the organ works:

The manner in which each new climax is begun, either by the addition of rhythmic interest or by the application of structural forms, shows a master hand and adds much to the worth of the architectural side of the work. With it all Mr. Sowerby does not for a moment lose sight of his spiritual values, which are always such a strong factor in his work. With all this in view the statement may be repeated that this passacaglia compares very favorably with any others with perhaps the exception of those by Brahms and Bach.

Available as additional tracks in online versions of the album.

Two Sketches H 393 (1963)

1. Nostalgic

2. Fancy-Free

World Premiere Recording

Among the works of Sowerby’s last decade, there are ample examples that conform to the composer’s description of his late period as his “Baroque Response” stage. There are also a few works that do not fit neatly into this classification, however — the best examples being these two little gems. Even knowledgeable Sowerby experts might guess they date from the late 1910s rather than the 1960s, even taking into account what was thought, until recently, to have been his first and only use of a tone-row.

The Two Sketches were the first solo organ works Sowerby composed after he retired from his Chicago posts at the American Conservatory and St. James Episcopal Cathedral to lead the College of Church Musicians at Washington National Cathedral. Health issues aside, these were happy years with honors and festivals galore, and a redoubling of his protean creative output: mostly choral works, but also his fifth orchestral symphony, second organ concerto, song cycle on Emily Dickinson poems, and even two carillon pieces. Most of these were specific commissions but the Sketches, written in April 1963 during a rare stretch when he composed nothing else, are tied to no commission or occasion. So far as is known, they did not receive their first performance until one of his former students, Adrien Moran Reisner, played them at Temple Emanu-el in Dallas in March 1965. The first of the Sketches, “Nostalgic,” is akin to the sensuous, atmospheric organ tone paintings that began with Sowerby’s Madrigal of 1915. One critic dubbed such pieces “mid-western impressionism” — two works from the 1940s, Arioso and the “very slowly” movement of his Sonatina, being the best known examples. Around this time, one of Sowerby’s students was a serial composer, so Sowerby’s use of a tone-row in “Nostalgic,” though notable, may simply be a demonstration to his student that the “old master” could learn a new trick. Or not so new: University of Alabama doctoral candidate, Jackson Borges, recently discovered hiding in plain sight the ground base of a chaconne — the fourth movement of an unpublished organ sonata written between 1914 and 1917, 50 years before “Nostalgic” — constructed of 12 non-repeated tones. The quiet, somber mood of “Nostalgic” is the perfect set-up for a classic Sowerby mood-swing into “Fancy-Free.” (Sowerby described himself as “The Jekyl and Hyde music,” referencing the variety of styles and influences heard in his 550 works “for every medium except opera.”) In these Two Sketches, he takes us from the late-Mahler, early-Schonberg tinged world of early experimentation in “Nostalgic” to the merry-go-round of the 1920s in “Fancy-Free.” Gordon Reynolds called it “a Waltonesque romp” in Musical Times and its one interpretative instruction, “Chipper,” could as easily describe the composer in the 1910s and 20s as enjoying his well-earned “second spring” in the 1960s. Lester Groom, a former Sowerby student, summed-up the Sketches and their composer in The American Music Teacher, “Dr. Sowerby in recent years has taken increased liberties with tonality, and his harmonic structures are bold and assertive… the romantic spirit endures, giving both the organist and the audience something to enjoy.”

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Recorded

Ferko August 24–26, 2019

House of Hope Presbyterian Church St. Paul, Minnesota

Sowerby August 17–20, 2020

St. Ita’s Catholic Church

Chicago, Illinois

Photos The organ at St. Ita’s

Elliot Mandel Photography

Graphic Design Bark Design

Publishers

Ferko

All works published by

E.C. Schirmer Music Company

Music for Elizabeth Chapel ©2002

Variations on Veni Creator Spiritus ©2006

Angels ©1999

Symphonie brève ©1999

Missa O Ecclesia: Communion ©1999

Variations on a Hungarian Folk Tune ©2006

Tired Old Nun ©2019

Mass for Dedication ©2004

Sowerby

Pageant ©1931

Fred Bock Music Company

Toccata ©1941

The H.W. Gray Co., Inc.

March from Suite for Organ ©1935 Oxford University Press

Symphony in G major ©1932

Oxford University Press

Two Sketches ©1964

Leo Sowerby Foundation

CEDILLE RECORDS © 2021

CDR 90000 204