| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

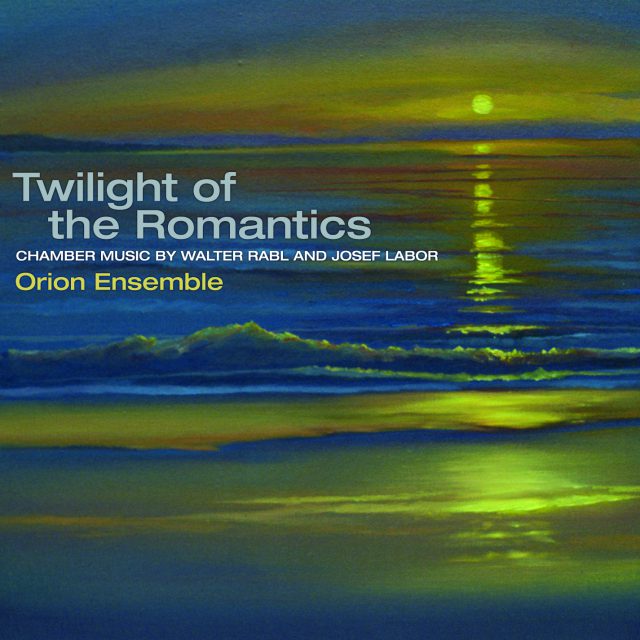

The Orion Ensemble – an unusual combination of piano quartet and clarinet known for its insatiable musical curiosity and stylish performances – makes its commercial recording debut with world premiere recordings of two forgotten gems from late-Romantic Vienna.

Walter Rabl’s Quartet in E-flat major for Clarinet, Violin, Cello, and Piano, Op. 1 (1896) and Josef Labor’s Quintet in D major for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, and Piano, Op. 11 (1900) are highly expressive, melodically rich musical journeys that share the same sound world as the late clarinet chamber music of Johannes Brahms, who enthusiastically championed Rabl’s quartet.

Preview Excerpts

WALTER RABL (1873-1940)

Quartet in E-flat Major for Clarinet, Violin, Cello, and Piano, Op. 1

JOSEF LABOR (1842-1924)

Quintet in D major for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, and Piano, Op. 11

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletTwilight of the Romantics: Chamber Music by Walter Rabl and Josef Labor

Notes by Bonnie H. Campbell

The works on this recording were written in an extraordinary time and place: Vienna on the brink of the 20th century. A visit to the “golden city” at the fin-de-siècle would have been the experience of a lifetime. Vienna was the major crossroads of Europe and among the five largest metropolises on the globe. Her residents were incredibly diverse, encompassing over twenty nationalities, five religious traditions, and twelve major languages.

With such a multiplicity of currents, it is little wonder that the “city of dreams,” as it was also called, was the locus of unprecedented cultural activity, where luminaries from virtually every arena of life interacted and informed each other’s work. Prominent personalities in art, architecture, literature, music, philosophy, psychology, and science tipped their hats to one another on daily noontime strolls along Vienna’s most famous thoroughfare — the Ringstrasse, toasted varying causes in her beer gardens, and sat side by side in her theatres and concert halls.

A few names will remind readers of the explosion of talent in Vienna at the time: Gustav Klimt in art; Adolf Loos, Josef Hoffmann, and Otto Wagner in architecture; Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Karl Kraus, and Arthur Schnitzler in literature; Johannes Brahms, Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schönberg, and Richard Strauss in music; Martin Buber in philosophy; Alfred Adler and Sigmund Freud in psychology; and Ernst Mach in physics. This confluence of cultural stars helped all the players polish their positions and created a cauldron of divergent ideas that would ferment and rise to change the world.

In music, as in other realms, the promise of a new century was accompanied by an acceleration of change and the birth of new ideas. The major defining ideals of romanticism — such as the supremacy of individual expression and the concept of organicism, which held that musical works had their own self-contained meaning — were beginning to lose currency. The heated debate about the course of music that had ignited in the 1860s following the arrival in Vienna of its two principle protagonists — Brahms and Wagner — was yielding to another, modernist discourse.

But as the shadows of the 19th century grew long, there came a final brilliant shimmer of romantic spirit. Brahms was drawn out of a self-imposed retirement by the superb playing of clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld. Upon hearing Mühlfeld in March 1891, Brahms immediately pledged to write new chamber works for clarinet. By the end of that summer, Brahms had finished both the Trio for Clarinet, Twilight of the Romantics: Chamber Music by Walter Rabl and Josef Labor Notes by Bonnie H. Campbell 5 Cello, and Piano, Op. 114 and the Quintet for Clarinet and Strings, Op. 115. Two years later, following the completion of the sublime piano pieces Opp. 116–119, Brahms again wrote for Mühlfeld. This time the result was the two Sonatas, Op. 120.

Unfortunately, these four magnificent works constitute Brahms’s entire output for clarinet. The pieces on this disc, however, could well be considered the finest examples of Brahmsian clarinet chamber music not written by Brahms. Both Rabl and Labor would have been well acquainted with Brahms’s late chamber works and quite possibly even heard them performed by Mühlfeld. Thus, it is probably no coincidence that both Rabl’s Quartet and Labor’s Quintet feature the clarinet as the only wind addition to the more established instrumentation of piano trio and piano quartet.

Given the ingratiating Viennese style and firstrate craftsmanship present in both pieces, it is natural to wonder why they fell into obscurity. The precise reasons are unclear, but probable causes can be hypothesized based on known circumstances. In the case of Rabl, his short career as a composer may have played a role. Rabl gave up composing at age thirty, turning his attention toward conducting and vocal coaching. As for Labor, his blindness may have limited his ability to disseminate and promote his works. Whatever individual factors may have been at play, both composers were eclipsed by Brahms — the standard bearer for “conservative” or “classical” romanticism. So, lacking Brahms’s reputation, the rise of modernism likely caused Rabl and Labor’s work to be relegated to the back shelf as “last year’s fashion.”

Today, the modernist style that obscured these works has itself yielded to postmodernism. It therefore seems fitting, with the benefit of hindsight at the beginning of yet another century, to review the life’s work of Rabl and Labor and rediscover their forgotten chamber music gems.

Walter Rabl

In 1896, eighteen compositions were submitted to a prestigious composition contest sponsored by the Vienna Tonkünstlerverein (Musicians’ Society), a group whose aim was to foster musical culture and whose honorary president was Johannes Brahms. The esteemed composer played an active role in this competition, donating prize money and serving as head of the adjudication committee.

According to critic Eduard Hanslick, Brahms “was a zealous promoter of competitions, especially chamber music competitions, to bring young talents to the fore. When it came to the examination of anonymous manuscripts that had been submitted, he showed astonishing acuity in guessing from 6 the overall impression and technical details, who the author was, or at least his school or teacher. Last year Brahms was very interested in an anonymous quartet whose author he was quite unable to identify. Impatiently he waited for the opening of the sealed notice. On it was written the heretofore entirely unknown name: Walter Rabl.”

As it turned out, Rabl’s Quartet in E-Flat Major for Clarinet, Violin, Cello, and Piano, Op. 1 caught the attention of the other judges as well and was awarded first prize. (The second prize went to Joseph Miroslav Weber, the third to Alexander Zemlinsky.) Brahms was so taken with the piece that he recommended it to his own publisher, Simrock, who released it the following year along with three other Rabl works: the Fantasy Pieces for Piano Trio, Op. 2, and two sets of Four Songs, Op. 3 and Op. 4. In 1899, Simrock published four additional pieces: Four Songs, Op. 5; the Violin Sonata, Op. 6; Three Songs, Op. 7; and the Symphony, Op. 8.

Walter Rabl was born in Vienna on November 30, 1873. In childhood, he became an accomplished pianist and was profoundly influenced by the works of the classical masters. Early on he moved to Salzburg, where he studied music theory and composition with J. F. Hummel, director of the Mozarteum, and graduated with honors from the Kaiserlich und Königlich Staatsgymnasium (Royal and Imperial State School) in 1892. Rabl then returned to Vienna in order to further his musical studies with theorist Karl Navratil.

After a period, he enrolled in the doctoral program at the German University in Prague as a student of noted musicologist Guido Adler. In addition to his regular studies, Rabl assisted Adler with research for the eightyeight volume Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich (Monuments of Music in Austria), along with another young composer, Anton Webern.

It was while he was a doctoral candidate that Rabl captured the composition prize. This success led him away from previous thoughts about a career in law and cemented his resolve to make his way in music. At twentyfive, he finished his Ph.D. and began to volunteer at the opera house in Prague. Soon after, he accepted a paying position at the Royal Opera of Dresden as coach and chorus master. His next series of compositions, Opp. 9–15, consisted entirely of songs and were published in Leipzig by Rahter.

Just after the beginning of the century, Rabl turned his attention toward opera. Up to this point his work had continued in the tradition of Brahms. But his opera, Liane, which premiered in Strasbourg in 1903, took a different turn. According to A. Eccarius-Sieber, “In larger circles of the musical world, conductor and composer Dr. Walter Rabl has made himself known through performances of his romantic 7 fairy tale opera Liane. Since this opera in its entire design and setting follows the Wagnerian artistic style while Walter Rabl — award-winning composer of a beautiful clarinet quartet — previously had been considered to belong to the Brahms faction, its appearance had to draw considerable attention.

Although this attention was highly favorable, Liane was Rabl’s last work. Based on comments made by Rabl’s son, Kurt, it seems that the critical comparison of Liane to Wagner’s operas so discouraged this Brahmsian disciple that he stopped composing and turned his energies more fully to operatic conducting. From 1903 until 1924, Rabl held a string of conducting posts throughout Germany and championed works by progressive composers such as Mahler, Goldmark, Schreker, Korngold, and Richard Strauss, and also directed many performances of Wagner’s music. In 1905, he married the Wagnerian soprano Hermine von Kriesten and conducted her in major roles such as Brünnhilde and Elektra. After his retirement from conducting in 1924, he continued to use his impressive piano skills in collaboration with many notable singers until his death in 1940.

Rudolf Felber states in Cobbett’s Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music, “Rabl’s chamber works are influenced by both Schumann and Brahms, but they are fresh and enjoyable compositions of considerable artistic worth, clear and simple in form, thoroughly natural and unforced in expression.” This description applies to the Quartet, which is the only known 19th century work scored for this combination of instruments, according to Rabl scholars John and Virginia Strauss. Rabl uses the myriad of possibilities inherent in this grouping to great expressive effect, masterfully combining a wide variety of textures into a cohesive, organic whole. Especially notable are frequent sonata-like textures for piano and one other instrument, often the clarinet. Like Brahms, Rabl employs traditional forms, but takes them further and is freer in his “play,” particularly with tempos, meters, and rhythmic material.

Not surprisingly, the Quartet’s opening movement in E-flat major is in sonata form and contains mainly conventional key relationships. The clarinet introduces the exposition’s two main themes, both of which are soft and lyrical. In contrast, the dramatic development, marked Vivo, introduces more motivic material, uses hemiola and other rhythmic devices, and quickly progresses through a wide variety of keys, eventually returning to the original tempo and snippets of the first theme in E major. Following the recapitulation in E-flat, the coda begins in D major and uses ascending melodic fragments to build to a final climactic reiteration of the theme in E-flat.

The second movement is structurally the most radical. It begins with a funeral march 8 that proceeds through a mazurka and a song, then morphs into a fugue, and ends with a march of triumph. In spite of six different tempo indications, two meter signatures, and a variety of textures, this movement is astonishingly cohesive. The third movement, only sixty-four measures, is in a simple song form (ABA) and epitomizes Viennese charm. Faint echoes of Johann Strauss can be heard in the B section. The finale, also in sonata form, explores vast harmonic territory even in the exposition. The development, using first theme motives, builds intensity via rhythmic manipulation. Following a slightly abbreviated recap, Rabl again creates energy through rhythmic means, this time with two striking meter changes in the coda.

Josef Labor

Although not directly mentored by Brahms, Labor had, in many respects, a stronger ideological connection with Brahms than did Rabl. Only nine years apart in age, Brahms and Labor had frequent contact in Vienna’s artistic circles, and Labor remained true to the “conservative” romantic vision for which Brahms was the figurehead.

Labor was born in 1842 in the Bohemian town of Horowitz. He was left completely blind by smallpox at the age of three and was subsequently sent to Vienna to attend the Institute for the Blind. Because he showed precocious musical talent, he was enrolled in the Konservatorium der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Conservatory of the Society of Music Lovers) where he studied composition with Bruckner’s teacher, Simon Sechter, and piano with Eduard Pickhert.

After finishing his formal education, he concertized as a pianist throughout France, England, Russia, and Scandinavia. Concurrently, he struck up an enduring friendship with King Georg V of Hannover, who was also blind. (The King had lost one eye due to a childhood illness and the other in a riding accident.) Georg was so enamored of Labor that he named him Royal Chamber Pianist in 1865. The following year, the two men settled in Vienna, where Labor began organ lessons with the famous church musician Johann Evangelist Habert and became a well-respected teacher, while continuing to compose and perform.

In 1904, Labor received the title Kaiserlich und Königlich Hoforganist (Royal and Imperial Court Organist) and is today best known for his organ works. Like many organists, Labor took a keen interest in early music. For example, he wrote continuo elaborations for Heinrich Biber’s sonatas that appeared in Guido Adler’s Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich (Monuments of Music in Austria) — the series that Rabl helped to edit.

As a teacher, Labor worked with many notable musical personalities including Julius 9 Bittner, Frank La Forge, Francis Richter, Alma Schindler (who became Alma Mahler), Paul Wittgenstein, and for a short time Arnold Schönberg. His relationships with Alma Schindler and Paul Wittgenstein are among the most documented and reveal much about his personality, life, and work.

Alma Schindler studied with Labor for six years, beginning when she was fourteen, and her diaries contain numerous references to her esteemed teacher. A few entries, as translated by Anthony Beaumont, offer a glimpse of their time together. On February 8, 1898 she wrote: “Labor. I’d learnt his pieces in secret, and today I played them to him. He was absolutely thrilled, made a few comments, then played me his latest organ work, nine variations on a theme (‘The Kaiser hymn’), for the forthcoming Jubilee. He played me the introduction, which is really magnificent.” On March 14, 1899: “Labor — last lesson [for a time]. He was as kind as ever, and blew kisses with the tips of his fingers.” On February 13, 1900: “Anniversary of Wagner’s death. This morning: Labor. . . . During the conversation his face assumed a strange, transfigured expression. That’s how I imagine a martyr must look. And indeed he is a martyr, a martyr for his art. I felt so sorry for him today. What has he had in life? Little recognition, little affection and — little money. And yet he said boldly: If I were born again, I’d still want to be an artist.” On May 8, 1900: “Labor. — We talked at length about our domestic problems. He’s like a father to me.”

Labor’s relationship with the famous pianist Paul Wittgenstein, son of Karl Wittgenstein, the wealthiest man in Austria and ardent supporter of the arts, is also revealing. When Paul lost his right arm to a Russian sniper’s bullet in WWI, Labor was the first person he asked to write a piece for the left hand only. (Paul later commissioned works from several other distinguished composers including Strauss, Ravel, Britten, and Prokofiev.) Paul wrote, “Before I as an invalid was exchanged and via Sweden returned to Vienna, I was held prisoner of war in Omsk (Siberia). From there I had — through the Danish Consul, Wadsten, sent a letter to Austria asking my former teacher, Josef Labor to compose a concerto for the left hand and orchestra for me. A couple of weeks later I received an answer that he was already working on it.”

Labor became a surrogate member of the Wittgenstein family. He attended an untold number of musical “abends” at the Wittgenstein’s famed mansion and there interacted with the most notable Viennese musicians of the day including Johannes Brahms, Clara Schumann, Gustav Mahler, Bruno Walter, and Richard Strauss. Paul’s brother, seminal philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (also an amateur clarinetist who reportedly played through Brahms’s sonatas with Labor), numbered Labor among “the six truly great composers” along with Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms.

Ludwig and Labor became close friends. Often when the philosopher returned from his teaching post at Cambridge, he would spend large chunks of time with Labor instead of his own family. For Labor’s 70th birthday the Wittgensteins urged Universal Edition to print some of his works and take over others that had already been published. Labor remained active until shortly before his death in 1924. At seventy-seven, he performed a well-received Buxtehude program at the Musikverein, the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde concert hall.

Although the exact date of composition for Labor’s Quintet is unclear, it was almost certainly written in early 1900. Alma Schindler mentions attending a rehearsal of the work on March 29. She wrote, “Yesterday p.m. I was at the Wittgensteins’ for the final rehearsal of the Baumeyer concert, which opened with a clarinet quintet by Labor.”

Like Rabl’s Quartet, the first movement of Labor’s Quintet is cast in a sonata form. It uses traditional harmonic pillars, but touches on many keys in transit, often with tertian (third) or slippery chromatic relationships. Labor frequently contrasts the sonority of the strings plus clarinet with that of the piano in concertante fashion. The second movement, a modified song form, begins with a folk-like melody in the clarinet, perhaps suggestive of Labor’s Bohemian roots. The B theme, marked molto appassionato, begins in the parallel minor (B-flat) and is sinuously chromatic. Its material develops in an increasingly fragmentary fashion, and this trend continues into the return of A, which this time is elaborated with cadenza-like material in the piano and clarinet.

The most unusual structure in the Quintet occurs in movement three, marked “Quasi Fantasia: Adagio.” It includes sixteen meter changes and almost as many tempo changes, along with sudden dynamic shifts. The first half is primarily a keyboard fantasia. This is followed by short solos in the cello and violin, and finally the violin leads directly into the last movement via a cadenza.

The finale is a theme and variations with changes of tempo, meter, and texture for each variation. Most of the variations retain the theme’s slightly asymmetrical phrase structure (8, 8, 9, 8, 5), and the listener has a sense that each variation builds upon the last, dramatically and sometimes thematically. The movement ends with a return, not to the theme of this movement, but to the opening material of the first movement, thus bringing the work full circle.

Bonnie Campbell, a freelance clarinetist in Chicago, holds degrees in music from Indiana University (D.M.) and the Yale School of Music (M.M.). In addition to performing regularly with pianist Diana Schmück as the Daedalus Duo, Dr. Campbell is a faculty member at the Merit School of Music and maintains a private studio

Album Details

Total Time: 57:46

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: February 3 (Rabl) and May 10-11 (Labor), 2005 at WFMT-Chicago

Steinway Piano – Piano Technician: Charles Terr

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Front Cover: Romance (oil on canvas) by Lee Campbell (Contemporary Artist). Private Collection. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

© 2006 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 088