Store

Store

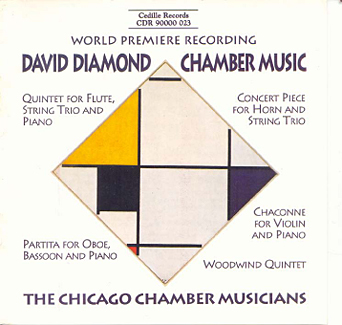

David Diamond Chamber Music

David Diamond’s symphonies have found their way into numerous record collections. Now, Cedille Records has produced the only CD devoted to his chamber music, including world premiere recordings of three works.

“I have heard many first-rate performances in my long life,” Diamond told Cedille president James Ginsburg. “But never have I heard the first-rate become remarkable, even extraordinary in the kind of perfection The Chicago Chamber Musicians have achieved. Add to their virtuosity and sensitive musicianship the superlative engineering and you have a composer’s dream come true. This CD has made my 80th year a very special one.”

According to Ginsburg, who produced the recording, “Listeners will discover music that’s as energetic, lucid, and meticulously crafted as the composer’s symphonies.”

The varied program unfolds like a well-planned concert, with Diamond’s modernist-influenced works interspersed with his neo-Romantic ones, and earlier works alternating with later pieces.

The energetic, neoclassical, tonally centered Quintet in B minor for Flute, String Trio and Piano (1937), appearing on CD for the first time, is followed by the world-premiere recording of the Concert Piece for Horn and String Trio (1978). With elements of atonality and dissonance but still basically lyrical, the Concert Piece is a complete contrast in sonority, mood, and atmosphere.

In the vivacious, contrapuntal Partita for Oboe, Bassoon, and Piano (1935), which helped launch the young composer’s career, Diamond retains a traditional form but fills it with contemporary themes, harmonies, and rhythms — as did Stravinsky and Schoenberg.

The world premiere recording of the seamlessly flowing yet imaginatively varied Chaconne for Violin and Piano (1948) is followed by the premiere of Diamond’s Woodwind Quintet (1958), a work reflecting the composer’s exposure to Schoenberg’s 12-tone serial technique, as refracted through Diamond’s uniquely faceted musical personality. It starts with serial procedure but transcends formula, winding up with instruments exchanging fragments that coalesce into lively melodic exchanges as they move toward a witty conclusion.

“Mr. Diamond provided us with many insights concerning the Wind Quintet’s composition, including his consultations with Schoenberg regarding serial technique as it relates in some ways to this amazing work,” says CCM oboist Michael Henoch.

CCM consulted with Diamond throughout the project. “He critiqued many of our taped concert performances of these works before we actually recorded them for Cedille,” Henoch says. “His advice was invaluable to us.” Concert audiences find the Diamond works engaging and enjoyable, Henoch observes. “The typical reaction is, ‘Why haven’t we heard this before?’ CCM has long prided itself on the diversity of its programming. “That each of these compositions has a different instrumentation plays to the strengths of the ensemble’s considerable resources,” Henoch adds.

Founded in 1986, CCM set out to become an internationally recognized Chicago institution dedicated to the study and performance of chamber music. Ten years later, CCM continues to win critical and popular accolades. In the words of the Chicago Tribune’s John von Rhein, “Even in a city well supplied with superior chamber ensembles, the Chicago Chamber Musicians are something special. The group . . . combines a dedication to the highest ideals of chamber music performance with a real flair for putting together zestful compelling programs. They make us glad to be sharing their music with them.”

Preview Excerpts

DAVID DIAMOND (1915 - 2005)

Quintet in B minor for Flute, String Trio and Piano

Partita for Oboe, Bassoon and Piano

Woodwind Quintet

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAbout the Program

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

David Diamond is one of many American musicians who went to Paris, and to Nadia Boulanger’s composition classes, in the years between the world wars; other established and aspiring figures who made the same artistic pilgrimage were Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. The mid-1930s were an important timer for Diamond, his ballet Formal Dance was premiered by Martha Graham’s company in New York 1935, and New York also heard his Psalm for Orchestra and Violin concerto No. 1 during these years. Among the many musicians he met during his time in Paris was Francis Poulenc, and the Quintet he wrote there in 1937 for flute, string trio, and piano has a certain Poulenc-ian flavor as the high -spirited energy of the other movements is contrasted with a very lyrical middle movement.

“The quintet for flute, violin, viola, cello, and piano,” Mr. Diamond relates, “was commissioned by the League of Composers for the Barrere-Britt Concertino and received its premiere March 8th, 1938, from that ensemble, at New York City’s Fifth Avenue Gallery. It won the Society for the Publication of American Music Award.” The Concertino, a group of solo performers who also enjoyed playing chamber music, was headed by the French-born flutist Georges Barrere.

The Quintet is officially in the key of B minor. The tempo marking of its first movement, “Allegro deciso e molto ritmico,” describes it well: vigorous, highly rhythmic themes are set out by the flutist and the string players, with piano contributions sometimes percussive and sometimes sustained. No one instrument is featured, though the flute has occasional short solos. The second movement is a Romance, “Lento, molto cantabile,” in which the strings are followed by the flute in introducing a songlike melody. The piano enters from a high, ethereal sphere to echo the theme. The instruments then expand on the theme together, with brief solos for piano and for violin, before retuning to the “echo” effects fog the movement’s opening. The finale, “Allegro veloce,” moves through rapid, propulsive triple meters with a dancing, folk-like theme that provides brief solo opportunities for the flute, the violin, and the piano.

Mr. Diamond tells us that the Concert Piece for horn, violin, viola, and cello “was composed in 1978 on commission from the students and friends of Dr. Arthur D. Hasler of Hawaii. I have no record of a premiere thee, but I have heard it was performed in Los Angeles, and about then years ago by members of the New York Philharmonic.”

The sonority, mood, and atmosphere of the Concert Piece are in complete contrast to the neo-classical, tonally-centered Quintet in B Minor. The horn work emphasizes the sinuous, contrapuntal intertwining of lengthy melodic lines whose contours are non-tonal, involving many second and seventh intervals, and half-tones, whose interactions produce some dissonant encounters. The difference in tone quality between the horn and the strings is sometimes emphasized, with the horn set off against its companions in passages akin to short fanfares, but is more often minimized, the horn being allowed to blend its lines and colors with those of the gentler strings. Through several tempo shifts the mood of the work remains fairly constant: lyrical, slightly melancholy, occasionally intensifying with passionate outbursts. Brief unison passages and episodes of vertical triadic harmony punctuate the music’s basically contrapuntal unfolding. The lively conclusion offers the horn a chance to stand out, as the strings wind down together.

“My Partita for oboe, bassoon, and piano,” writes the composer, “was composed in 1935 and received its first performance at a league of Composers concert on March 29th, 1936. It was among the first of my chamber-music works heard in New York, and was highly praised by Aaron Copland and Roger Sessions in the pages of Modern Music. In three tightly-organized movements, it can be considered in sonatina form.”

Diamond, like other 20th century composers, Stravinsky and Schoenberg among them, is fond of retaining traditional forms established during the Baroque and Classical eras, while crafting the content for theses structures – the themes, harmonies, and rhythms – out of wholly contemporary material. Partita” is a term that Baroque composers sometimes used as a synonym for Dance Suite. This Partita is not based on dance rhythms, but does recall Baroque music by its emphasis on contrapuntal writing. Like the Quintet in B Minor, it recalls Poulenc: in it Gallic, neo-Classical atmosphere, in its scoring for an instrumental grouping that Poulenc used in a 1920s Trio, and in its nature as a “little sonata” (sonatina).

Rapid passage-work for all three players at the start of the opening “Allegro vivo” movement leads to a more lyrical woodwind duet with keyboard commentary; lively piping by both oboe and bassoon brings the movement to an end. The bassoon opens the “Adagio espressivo” central movement with a lyrical theme on which the oboe elaborates; the piano adds commentary to the passage that is slow and contemplative in feeling. The bassoon ends the movement on a mournful note, a mood immediately dispelled by the perpetual-motion jollity of the “Allegro molto” finale, which is characterized by repeated-note patterns in quick succession, and canonic imitations between the two woodwind players.

The Chaconne for violin and piano, like the Partita, takes its name from Baroque music; a Chaconne, for Bach and Handel, was a continuous set of variations an a basic melodic-harmonic pattern. Diamond writes that his Chaconne “was composed in 1948 on commission from the violinist Jean Westbrook. She performed the work for the first time on her debut Town Hall (New York cit) program, with Eugene Helmer the pianist, on October 20th, 1949. the entire work is structured around the wide leaped ostinato of the opening and the variations on the long-lined melody heard immediately after.”

The opening theme, for violin, involves large spaced intervals: sevenths, octaves, and ninths. Even more important in the on-flowing variations that constitute the work is the violin’s ensuing lyrical theme, supported with piano chords. Henceforth, violin and piano lines are interwoven in imitative counterpoint. There are very few pauses in the Chaconne, few interruptions in its forward progression, though there are numerous tempo changes, with the pace and intensity of the melodic and rhythmic lines speeding up and slowing down in frequent succession. Both instruments explore their full rages; the violin varies its basically sustained texture with episodes of pizzicato and tremolo, with double stops and octaves. The string player also has a brief cadenza-like solo before the work’s rapid, upbeat conclusion.

The year the Chaconne was written, 1948, was also the year Diamond first met Arnold Schoenberg, who developed serialism, the method of composing with 12 tones. Impatient with rigid “schools” of composition, or with trends f any sort, Diamond has consistently forged his own style, always speaking in his own voice. A practicing musician who worked as a free-lance violinist between commissions for new works, he values individuality, independence, and professional craftsmanship more tha abstract theories. The serial approach to composition, with themes generated by a strictly-ordered “row” of 12 tones, can be viewed as a mindless method of musical organization – a kind of non-electronic computer – or it can be considered a starting point with a mind and a heart to carry it forward into the creation of real music. Schoenberg used it that way, and so did composers who followed him in the new technique, whether or not they used it consistently.

Diamond’s Wind quintet of 1958 is one of his responses to the experience of Schoenberg and the Schoenberg school; it is a work that starts with serial procedure but transcends formula. “The Quintet for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn,” he writes, “was commissioned by the Fromm Music Foundation. It received its premiere from the Boston Symphony Ensemble at Tanglewood on July 14th, 1958. It is in three movements: the first a sonata-allegro; the second a theme and variations with a Scherzino interlude; the third a rondo with fugal elements. The motives derived from a 12-note row heard at the opening of the first movement, and various transformation of the row.”

The opening movement has a 13-measure “Andante grazioso” introduction that sets out the tone row in a series of melodic fragments. In the movement’s main “Allegro” section, these fragments are extended into more recognizable motives, as the instruments begin to play together; the horn occasionally stands apart from its companions.

The chromatic melody of the variations movement is presented by the flute, oboe, and clarinet, with horn and bassoon entering as if form a distance. These distinctions between the higher-and lower-voiced instruments characterize the movement, except for the Scherzino (Little Scherzo) interlude, wherein fast-paced duos and trios among various players are contrasted with unison passages.

The Woodwind Quintet’s finale is labeled “Allegro fugato.” Just as this piece, with its freely interpreted 12-tone row is not completely serial, so the fugato is not a completely worked out fugue; it’s different from the way Bach would have laid out a fugue for organ in that it is not so strictly formulated. “Music in the fugal manner’ would describe it. This finale, like the Quintet’s opening, finds the instruments exchanging thematic fragments that later coalesce into lively melodic exchanges, each instrument imitating each other’s patters as the propulsive movement works its way toward a witty conclusion.

Album Details

Total Time: 61:25

Recorded: March 16, April 19 & 20, 1995 in Bennet Hall at Ravinia, Highland Park, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Diagonal Composition (1921), Piet Mondrian. Courtesy of Mondrian Estate/Holtzman Trust, Essex, CT. Photograph © The Art Institute of Chicago

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Richard Freed and Andrea Lamoreaux

© 1995 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 023