Store

Store

The World of Lully

Chicago Baroque Ensemble, Patrice Michaels

John Mark Rozendaal, Anita Miller-Rieder, David Schrader

The movie that sparked interest in French baroque music, 1991’s Tous les matins du monde, centered on viol virtuoso Marin Marais and his teacher Sainte-Colombe. But music in the age of Louis XIV actually revolved around the formidable composer and impresario Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), the dominant star in the Sun King’s musical galaxy.

On this CD, the Chicago Baroque Ensemble and soprano Patrice Michaels take listeners beyond the viol repertoire popularized by the French film. Here, on a single CD, are solo and chamber arrangements of Lully’s vocal and instrumental theater music. Intimate arrangements such as these were widely performed in salons during Lully’s lifetime and long thereafter.

For the sumptuous court at Versailles, Lully created music that would “soothe the ear and delight the senses . . . elegant, clear, and well-ordered” (Joseph Machlis, The Enjoyment of Music). Lully combined large baroque gestures with the minute refinement of the French “precieux” style, writes John Mark Rozendaal, the Chicago Baroque Ensemble’s artistic director. “Perhaps it is this uncommon interplay between intimate and corporate expression that makes Lully’s opera music so satisfying in chamber music renditions,” Rozendaal says.

The two Lully divertissements on the recording, arranged by the Chicago Baroque Ensemble, comprise song an dance sequences from Alceste, Amadis, Armide, Ballet d”alcidiane, Ballet de l’amour malade, Ballet Des Plaisirs, Persée, and Phaeton.

The Galliarde from Trios pour le coucher du roi shows Lully working in the Italianate trio sonata format. La Plainte de Cloris, with words by Molière, is part of Lully’s Le Grand Divertissement Royal de Versailles, a self-contained royal entertainment. Armide, Lully’s last completed opera, contains some of his most renowned music.

Lully protégés Marais (1656-1728) and Jean-Féry Rebel (1666-1747) each wrote a “Tombeau,” a heartfelt musical tribute, to Lully. (Lully had, in a sense, “shot himself in the foot”: He accidentally stabbed his own foot with the long conducting stick he used to beat time and died from an infection.)

Jean-Henri d’Anglebert, a harpsichord virtuoso who was present at Lully’s original productions, wrote arrangements of Lully’s works. D’Anglebert’s efforts show a mastery of counterpoint, ornamentation, and the harpsichord idiom.

Preview Excerpts

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632–1687)

Premiere Divertissement

JEAN-FÉRY REBEL (1666-1747)

Le tombeau de Monsieur Lully

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY

Seconde Divertissement

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY arr. Jean d'Anglebert

Pieces de clavecin

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY

MARIN MARAIS (1656–1728)

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY

Armide, Tragedie lyrique

Artists

1: Chicago Baroque Ensemble with Patrice Michaels

8: Chicago Baroque Ensemble

13: Chicago Baroque Ensemble with Patrice Michaels

18: David Schrader

21: Chicago Baroque Ensemble with Patrice Michaels

22: Chicago Baroque Ensemble

24: Chicago Baroque Ensemble with Patrice Michaels

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe World of Lully

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

The life of Jean-Baptiste Lully was marked by such deep contradictions, both real and widely attributed, that it becomes difficult to gauge the true essence of this extraordinary figure. A great composer, wealthy entrepreneur, buffoon, tragedian, native Italian, icon of French nationalism, notorious sodomite, and excellent husband and father, Lully’s combined traits and achievements suggest a powerfully mercurial personality. His colleagues’ love and loathing survived long after his death in 1687.

Born in Florence in 1632, Lully traveled to France in the retinue of Roger de Lorraine, who had recruited Lully as a valet de chambre for Mlle de Montpensier, “la Grande Mademoiselle.” From this politically disadvantaged “mail-room” position, Lully began his astonishing, uninterrupted rise to fame and fortune, somehow turning every disaster to his own advantage. Two examples will suffice to illustrate the Florentine’s cat-like ability to land on his feet. In 1652, while Lully was still in the employ of Mademoiselle, Louis XIV was seriously threatened by a revolt of a set of nobles known as the “Fronde.” When the Fronde was finally defeated, Mademoiselle was forced to leave the capital in disgrace, exiled to her country home with her entire staff. At precisely this point where our hero might have been condemned by association and consigned to historical oblivion, Lully managed to get himself released from Mademoiselle’s service and appointed at the court of the young king. Another crucial maneuver occurred in 1671. Having dismissed opera as a foreign genre unsuited to the French language and culture, Lully was surprised when Pierre Perrin’s Pomone became an immense popular success. What should have been a triumph for his competitor became a coup for Lully when Perrin’s fiscal ineptitude landed him in debtor’s prison and enabled Lully to purchase an exclusive patent for the production of theatrical music at extremely favorable terms. Overnight the anti-opera Italian became the despot of the new-born French opera.

These paradoxes are embodied in Lully’s music and its reception. Lully’s masterpieces, the great ballets and tragedies lyriques, were created simultaneously as both court rituals, events of unlimited splendor laden with coded meanings about the status of the monarch, and as commercial ventures for a wider urban public. The music itself marries the “colossal baroque” with the characteristically French “precieux” style. Here, moments of grand spectacle deploying large musical forces take their meaning from minute refinements of style, attitude, and execution. This artistic integration of the public and personal gestures is in tune with the cultural spirit of the time. A common theme of the classic drama of the grand siècle (including the Quinault texts set by Lully) was the careful balancing of opposites within the personal realm, passion tempered by reason, love directed by duty or “glory.”

Perhaps it is this uncommon interplay between intimate and corporate expression that makes Lully’s opera music so satisfying in chamber music renditions. This potential in Lully’s music, seldom realized today, was certainly not lost on the composer’s contemporaries and eighteenth-century successors. Much as the music of today’s Broadway musicals spreads through our popular culture through dozens of outlets several steps removed from the original production (recordings, sheet music, movies, performance of excerpted songs), Lully’s compositions became an essential part of the musical vocabulary of Europe through its dissemination in all manner of arrangements including printed souvenir “skeleton scores,” string quartet arrangements, and hundreds of manuscripts of harpsichord transcriptions. Lully thus remained a staple of salon music and of the French theater for a full century after the composer’s death. In the spirit of this practice, our program presents excerpts from Lully’s theater music in solo and chamber music arrangements.

The two “divertissements” on our program are song and dance sequences we devised, drawing from different works by Lully. The Galliarde is found in a manuscript from c.1665 containing trio arrangements of Lully’s theater music, works by Marin Marais, and original chamber works of Lully without concordances in surviving operas or ballets. The existence of these works gives Lully a place in the history of chamber music in France as one of the first to work with the Italianate trio sonata scoring.

Armide was Lully’s last completed opera. Quinault’s libretto treats a famous episode from Tasso’s Gerusaleme liberata. The story, in which the sorceress Armide fails in her attempts to seduce the Christian knight Rinaldo, is perfectly suited to the seventeenth-century tradition of court dramas in which women who attempt to use their power to influence men come to bad ends (Dido, Medea, Cleopatra, Platée, Ariadne). Lully’s setting contains some of his most renowned music, items that were recalled as models by later generations of French musicians. The overture (which opens our first Divertissement and, therefore, this disc) was so admired by Corelli that he framed a copy of it to hang in his dining room. The third act recitative (Enfin il est en mon puissance) is a recognized masterpiece of dramatic declamation in which dramatic shifts of register, speech rhythm, and harmonic pacing are all deployed to portray the divided mind of the anti-heroine. The great Passacaille of Act IV is heard here in d’Anglebert’s keyboard arrangement. In the final monologue (Le perfide Renaud me fuit) a second episode of emotional confusion is portrayed, this time with the support of rich instrumental accompaniment.

After his death, Lully was the subject of innumerable literary and musical tributes, including both satirical works lampooning the Lullian cult of personality and the controversies around it, and sincere, heartfelt eulogies by admiring students and colleagues. One of the most famous is Couperin’s Apothéose de Lully depicting Lully’s reception in Parnassus by Corelli and the muses (less sympathetic writers depicted Lully’s posthumous fate more ominously). The two “Tombeau” compositions on our program are psychological explorations of grief, each evoking a transforming progression of emotional states.

As a young man, Jean-Féry Rebel (1666-1747) was a violinist in the famous Vingt-quatre violons, the royal court orchestra led by Lully. Rebel’s tribute to his mentor is a spooky drama of loss and remembrance in the modern form of an Italian sonata haunted by the sounds of the past. The figures of the opening Lentement are delicately poised between the theatrical and the precieux, simultaneously invoking the grandeur of an opera overture and the intimacy of tender sighing. A contrapuntal “canzona” movement marked Vif (Italian style) is followed by a second Lentement consisting of a brief récit — a sort of eulogy spoken by the viola da gamba — and a very gracious Air in triple meter (both in a more retrospective French style). The extensive Vivement that follows attempts to return to the modern sonata style, but is thrice interrupted (haunted!) by mysterious throbbing motifs. With each return to the quicker tempo the emotional pitch is raised until the music ignites into a frenzy of bowed tremolo. The opening Lentement returns renamed, Les Regrets.

Jean-Henri d’Anglebert (1635-1691), the finest claveciniste of his generation, entered the royal service in 1662. His single publication (1689) includes both original compositions and arrangements of works by Lully. Such arrangements survive in many sources by many musicians. Those of d’Anglebert have particular authority because d’Anglebert was present at the original productions. Their extraordinarily rich sound is the result of his mastery of counterpoint, ornamentation, and the harpsichord idiom.

Marin Marais (1656-1728) was a student of Lully and the greatest virtuoso of the French school of viola da gamba playing. His first volume of pièces de viole appeared in 1686 with a dedication to Lully:

Monsieur, it would be inexcusable if, having had the honor of being one of your students, and being attached to you by other special obligations, I were not to offer to you these essays of what I have learned in performing your knowing and admirable compositions. I therefore offer this collection to you as my supervisor and benefactor. I present it to you also as to the first man who has ever been in all the diverse characters of music. None would contest this title. The greatest experts confess that there is no way more sure or more easy to succeed in this profession than by study of your work. All of the princes of Europe who wish this art to flourish in their states recognize no other way. But whatever their advantages may be, they will always leave something to be desired. Only one thing has fulfilled your desires and covered you with glory: that is to have pleased Louis the Great, and to have given to posterity airs to celebrate the name and famous exploits of this monarch. Your songs alone are worthy to accompany his immortal history. They will go with it to all nations. We have already seen people attracted by the renown of his greatness come from distant climates and return charmed by your songs as much as astonished by the majesty of the hero for whom you compose them. What fruits of your labors! But at the same time what honor for me to have such an illustrious protector as you and to be able to bear witness to you daily by my attachment and my respect. I am your very humble, very obedient, and very indebted servant, Marais.

By the time Marais’ Seconde livre de pièces de viole appeared in 1701, his mentor had died. Here Marais paid tribute to his teacher with one of the most moving musical elegies of the century. Marais’ noble melody explores a wide range of heightened emotional states in a technically superb composition; a fitting tribute to the father of French music.

John Mark Rozendaal is artistic director of the Chicago baroque Ensemble.

Album Details

Total Time: 77:37

Recorded: March 17, 18, 24 & 27, 1998 at WFMT, Chicago, IL

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

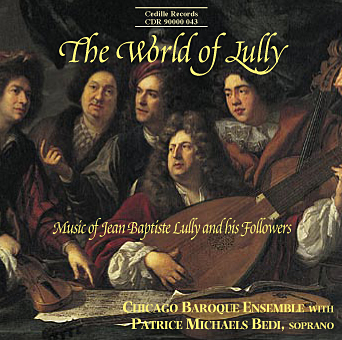

Cover: Reunion de Musiciens, Francois Puget (1651-1707) Louvre © Photo RMN

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: John Mark Rozendaal

© 1999 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 043