Store

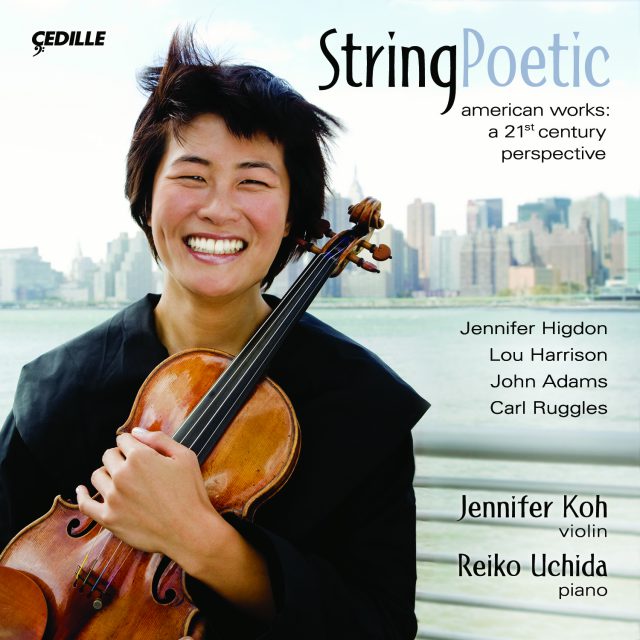

One of music’s brightest young stars, “prodigiously talented” (The New York Times) violinist Jennifer Koh presents a hand-picked program of inventive and attractive American works for violin and piano, spanning the 20th and 21st centuries.

The album takes its name from Jennifer Higdon’s String Poetic (2006), written expressly for Ms. Koh — a world-premiere recording. Its diverse moods, harmonic approaches, and styles take full advantage of Ms. Koh’s wide musical palette.

The CD also features Carl Ruggles’s atmospheric and enigmatic Mood (1918); Lou Harrison’s dance-infused Grand Duo (1988), and John Adams’s propulsive Road Movies (1995).

Ms. Koh’s “penetrating intelligence,” “white-hot imagination,” and “focused, sweet-toned playing” (Washington Post) are brilliantly displayed on this album of exhilarating American discoveries.

Preview Excerpts

JENNIFER HIGDON (b. 1962)

String Poetic

CARL RUGGLES (1876-1971)

LOU HARRISON (1917-2003)

Grand Duo

JOHN ADAMS (b. 1946)

Road Movies

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe American Violin: Big, Bold, Singing, Striving. A 21st-Century Perspective on Four American Originals

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

- Jennifer Higdon b. 1962, born in Brooklyn, resides in Philadelphia

- Carl Ruggles 1876-1971, born in Massachusetts, died in Vermont

- Lou Harrison 1917-2003, born in Oregon, died in Indiana

- John Adams b. 1947, born and raised in New England, resides in California

Jennifer Higdon wrote String Poetic for Jennifer Koh, who premiered it with Reiko Uchida at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia in October 2006. With Christoph Eschenbach and the Philadelphia Orchestra, Koh recently premiered a concerto Higdon wrote for her. Titled, “Singing Rooms,” this joint commission from the Atlanta Symphony and Minnesta and Philadelphia Orchestras is scored for violin, chorus, and orchestra. “I’m really excited,” Higdon has declared, “by… all the possible colors this combination presents.” Speaking with composer Kirk Noreen in a 92Y (New York City’s 92nd Street Y) Blog interview, Higdon also expressed enthusiasm about the piano concerto she recently completed, an upcoming bluegrass concerto for the group Time for Three – “I… identify with the sound, having grown up in East Tennessee where bluegrass is prominent,” and a violin concerto she is writing for Hilary Hahn. These challenging projects are the latest in a long line of commissions for this much-admired and performed composer who has written for the Philadelphia Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, eighth blackbird, Tokyo String Quartet, and numerous other groups. One of the most-played works by a living American on symphony-orchestra programs nationwide is her Blue Cathedral.

When asked about the genesis of String Poetic, Higdon cited Koh’s “virtuosic abilities and soulful playing. Because I have heard her play so many different types of music, I created a piece that has different moods: almost like a small story book.” Moods and styles vary widely during the approximately 20 minutes of this five-movement violin-piano suite. A special element of interest in the piano part is the use of stopped (muted) strings in the odd numbered movements. The keyboard tone color changes and softens, though the notes are still heard; Higdon says she was seeking a slightly “odd” sound world. Though each movement is an individual unit of sound, style, and mood, the piece is unified by the thematic links between the first and last movements, “Jagged Climb” and “Climb Jagged.” The tempo indication for each is the same: quarter note equals 152, a very fast pace indeed. In these two movements, the violinist alternates between normal bow strokes and playing “sul ponticello”: on the bridge of her instrument, which produces a drier, less resonant sound than when the bow is drawn in its normal position, halfway between the bridge and the base of the fingerboard. The effect is one of headlong, breathless mobility. After the “Jagged Climb” — up a cliff, perhaps? — we have an interlude of contemplation called “Nocturne: gentle, serene, and lyrical.” Higdon makes another word play in her description of this movement: “that piece of night, night of peace.” About “Blue Hills of Mist,” she told Kirk Noreen, “The third movement I wanted to be the heart of the piece, with stopped notes in the piano [like ‘Jagged Climb’], but slower moving and much more contemplative and profound sounding.” The piano has a complex introduction, after which the violin enters and explores its whole range with wandering themes. The piano part intensifies into huge chords. While claiming she’s not a poet with words, Higdon appended evocative descriptions to each movement; for “Blue Hills of Mist,” she wrote: “In the glaze of light between dawn… and sunset, blue’s hills have mist — a covering of song and mystery that belongs not to any person, but to other places.”

Citing the fourth movement, “Maze Mechanical,” as a tribute to minimalism, Higdon sets a moderately fast pace and adds, “Precise, like a machine.” Koh thinks this movement was influenced by Road Movies. The piano sets the pace with dotted, syncopated rhythms; short motives dominate the thematic material over ever-changing harmonies. Higdon calls this movement “Amazing maze; maze that is mad; mechanical machine… mechanical maze.” Then she ratchets up the tempo for the final “Climb Jagged,” echoing the first movement thematically and rhythmically. The composer’s description here: “Rise above, in jagged climb… climb, arise, in jagged run… running, rise, jagged fun.”

Carl Ruggles would have appreciated Higdon’s title and descriptions for String Poetic, since his music was frequently inspired by English and American poets of the Romantic age, including Whitman, Browning, and Blake. His fondness for poetry is a characteristic he shared with his better-known friend and contemporary, Charles Ives. With Arnold Schoenberg, Ruggles shares the distinction of being an exhibited painter as well as a published and performed composer — though performances of Schoenberg’s work, relatively rare as they may seem, are frequent compared to the few chances we ever get to hear Ruggles’s music. He is, today, a virtual unknown, but he had been known to and admired by some of the major rebels in American music: Ives, Edgar Varèse, and Henry Cowell (his friendship with Cowell links him to Lou Harrison). In Ruggles’s case, though, rebellion veered into eccentricity. He worked obsessively over his scores, very few of which were ever published. Despite a lifetime spanning almost a century, he left behind only a small public legacy — plus prodigious bundles of sketches that never evolved into finished compositions, some as brief as a single measure notated on scrap paper.

Ruggles learned to play the violin from his mother, then worked as a Boston-area theater violinist while studying theory with one of the arch-conservatives of American music in the late 19th century, John Knowles Paine. Ives also studied with Paine at Harvard; neither pupil seems to have absorbed much of the older man’s reverence for European traditions. Expanding his horizons and career possibilites, Ruggles moved with his wife to Minnesota, where he founded and conducted an orchestra and started work on a now-lost opera, The Sunken Bell. He moved back East, where some of his music was performed and he became associated with the International Composers’ Guild formed by Edgard Varèse. In the mid-1920s, the Ruggles family moved to Vermont, where the composer lived for most of the rest of his life, part of the time in a refurbished one-room schoolhouse. He continued to revise and re-revise his work while becoming increasingly reclusive, painting and working endlessly on bits and pieces of music. He died in 1971 at the age of 95, not precisely forgotten: remembered only with affectionate puzzlement by the general musical public but with profound admiration for his originality and tenaciousness by those who really knew him.

Though he knew of Schoenberg’s development of 12-tone composition and admired Alban Berg, Ruggles didn’t directly adopt the methods of the Second Viennese School. His own compositional evolution led him independently to decide not to repeat notes until most of the others in the chromatic scale had been set out, and he often used octave transposition to get around the need to repeat a tone in the same pitch range. This kind of approach can lead to wide ocatve leaps, intervals of major and minor sevenths, major and minor ninths, and tritones: half-octaves that may be viewed as either augmented fourths or diminished fifths. The “melodic” patterns thus created are wild and wandering. Ruggles sought dissonance, not consonance; he deliberately produced difficult and powerful music out of a sense of heaven-storming defiance.

After Ruggles’s death, his friend and colleague, pianist John Kirkpatrick, undertook to sort through the mountains of sketches and complete some of the works Ruggles labored over for decades. One such piece is Mood for violin and piano, of particular interest to Ruggles aficionados because it appears to be his only work featuring a solo part for Ruggles’s own instrument. The sketches for Mood date from about the same time (1918) as his work on The Sunken Bell, the score of which Ruggles neither finished nor preserved. He inscribed the sketches with the following lines:

Our world is young

Young, and of measure passing bound

Infinite are the heights to climb

The depths to sound.

Kirkpatrick transcribed the various sketches into a short, atmospheric piece that may or may not reflect Ruggles’s original intention. (He gave it, at one point, another title: “Prelude to a Tragedy.”) The result, however, attests to Kirkpatrick’s admiration for Ruggles’s unique genius, and to his own ability as a musical craftsman. The opening violin motive recurs recognizably, though varied, throughout the piece to create a kind of rondo effect. The inconclusive interval patterns of the 12-tone approach are apparent in the lines for both violin and piano, which echo and reinforce each other through clusters of chords and octaves, and an abundance of those dissonant intervals of sevenths, ninths, and tritones. And what is the mood of Mood? One of exuberance and energy, of clashing lines that never quite resolve and yet fit, singing in a unique voice, expressing a message of aspiration and striving (toward something that perhaps only Ruggles could fully hear). In spite of Kirkpatrick’s reconstruction, it remains in a sense unfinished, echoing what Ruggles meant when he wrote: “Creation is soul-searching. Nothing is ever finished.”

One of Lou Harrison’s many contributions to the diversity of the American musical scene was his incorporation of the sounds and structures of Southeast Asian gamelan music into the Western world’s symphonic tradition. Gamelan was only one influence on his work, which also reflected the innovations of Schoenberg and Henry Cowell (one of Harrison’s teachers), a fondness for Renaissance and Baroque music, and Harrison’s own explosive creativity. A friend and mentor was Virgil Thomson, a quite different composer stylistically, but one who understood Harrison and captured him in these words: “[His music’s] message is of joy, dazzling and serene, and even at its most intensely serious, not without laughter.” Harrison died suddenly on a wintry night in Lafayette, Indiana, en route to a festival of his music co-sponsored by Ohio State University and the Columbus Symphony Orchestra. Joshua Kosman’s obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle included this penetrating assessment: “What united all his music… was its essentially melodic nature. Whether shaped by medieval French dance rhythms, Javanese modes or Korean harmonies, melody always was Mr. Harrison’s primary building block.” John Adams’s comment from the winter of 2003 reflects his own artistic evolution: “He was one of the very first composers to bring back the pleasure principle. For those of us who came of age during the bad old days when rigor and theory and the atomization of musical elements were so in vogue, Lou provided a model of expressivity and sheer beauty.”

Composed in 1988, Grand Duo was choreographed by Mark Morris in 1993 (all except the fourth movement): fitting, since Harrison wrote a number of original dance scores and taught the craft of composing for dance. The five movements draw their inspiration from 18th-century models — Prelude, Rondo, Aria — and from dance genres: the lively medieval Estampie and the equally lively Eastern European polka. In the Stampede (estampie) and Polka movements, the pianist employs an octave bar that allows her to execute complicated octave patterns in very fast tempi and emphasizes the piano’s percussive nature. The Prelude’s main section is anchored by steady 8th-note patterns in the keyboard part, while above, the violin weaves rhapsodic melodies that ruminate through chromatic patterns, leaping and soaring. The keyboard’s ostinato is replaced by an octave passage that leads to a violin cadenza, after which the opening section is recapitulated to create a classic A-B-A structure.

Stampede restates an ancient dance style as a fiddling American hoedown. The violin has double stops and rapid run passages over related piano themes laid out at first in 8th notes. A wandering violin melody leads to colorful octave clusters in the piano part, countered by insistent repeated-note patterns in the violin. The violin’s double stops return and are expanded into huge chords. Then, as if spent, both players come to a sudden, emphatic conclusion. The mood changes completely for the Round, which fluctuates between D Major and B Minor while never settling on either one, thus echoing the unemphatic quasi-tonality of medieval modes. The melody laid out at the beginning is constantly elaborated and varied, with quarter-note and 8th-note patterns gradually intensified by movement in 16th notes. The piano is quieter here, and both instruments move to a serene ending. In the Air, the piano plays a slow, dramatic opening mostly in its lower and middle registers. The violin slides in with a sad song that explores its whole range, lowest to highest, seemingly directionless. The mood intensifies from a gentle rocking to a passage of insistent octaves. The opening material returns, varied, and once again the instruments drift apart: the piano stays low, the violin drifts away high.

After the serenity of the Round and the melancholy of the Air, we’retreated to a rollicking Polka that once again features the piano’s octave bar for brilliant keyboard sound effects. The violin part is full of double stops, chords, and pizzicato to punctuate the robustly cheerful polka melody and provide a dazzlingly virtuosic ending.

John Adams’s collaboration with stage director Peter Sellars on the opera Doctor Atomic has won tremendous acclaim as a triumph of musical theater. His career as an opera composer has followed a line of commentary on non-musical issues. Previous collaborations with Sellars include Nixon in China, focusing on the ironies of diplomacy and the differences between capitalist and planned economies, and The Death of Klinghoffer, which evoked controversy by representing the terrorist point of view onstage. Doctor Atomic spotlights the moral issues of war heightened by the creation of the first weapon of mass destruction. In strictly musical terms, Adams has cited his experiences in the world of opera as a factor in his change of attitude toward melody. “A breakthrough in melodic writing came about during the writing of The Death of Klinghoffer, an opera whose subject and mood required a whole new appraisal of my musical language.” This new appreciation for melody led him, in the early 1990s, to chamber music “with its democratic parceling of roles, its transparency and timbral delicacy, [and] the challenge of writing melodically, something chamber music demands above and beyond all else.” Road Movies dates from 1995, in the wake of Adams’s Chamber Symphony and his string quartet titled “John’s Book of Alleged Dances.”

The astonishing scope and variety of Adams’s achievement have made him one of the most admired and performed of living composers. A long-ago and misleading evaluation pigeonholed him as a minimalist. Minimalism is an inexact and sometimes dismissive term that leads to little musical understanding; the intent of the repetitiveness of motives and rhythms is not to “minimize” anything, but to intensify the aural experience and force the listener to change her perception of time. The perception of both time and motion is a major theme of Road Movies, whose first and last movements feature the insistent reiteration of small thematic cells and constant rhythmic patterns in a manner derived from the minimalist tradition. The textures in the outer movements are a decided contrast to the movement they surround, a centerpiece both more melodic and more moody. “Road Movies is travel music,” says Adams, “music that is comfortably settled in a pulse groove and passes through harmonic and textural regions as one would pass through a landscape on a car trip.”

Jennifer Koh’s acquaintance with Adams led to her interest in Harrison’s music. She and Adams first met when he conducted her as soloist in Harrison’s Concerto in Slendro at the September 2003 inaugural concert for Carnegie’s Zankel Hall. Adams told her of the influence Harrison’s music exerted over his recent concerto for electric violin titled “The Dharma at Big Sur.”

To the composer’s metaphor of a car trip, the violinist adds her view that the piece could also represent a train trip. In First Movement: Relaxed Groove, the piano provides an insistent ostinato rhythm that echoes the sound of tires against pavement or of a train’s wheels clicking over track at a steady speed. The violin, meanwhile, has a series of short melodic patterns that evolve subtly and build gradually in intensity. “Material is recirculated in a sequence of recalls that suggest a rondo form,” writes Adams. The piano represents the mechanical, physical aspect of the journey, while the freer violin conveys the passengers’ and driver’s visual images as road and scenery unwind before their eyes.

Adams specifically cites a desert landscape for Second Movement: Meditative. Koh calls this section a conversation between violin and piano (perhaps the passengers and driver have decided to talk instead of looking out at the endless desert sands?). The violin’s G string is tuned a full step down to F, giving the part extra low range. The piano starts with a contemplative, serene melody shortly picked up by the violin; it evolves and expands, shared between both players as a kind of dialogue. The mood and pace intensify as the players begin to play their lines together instead of in dialogue, but the “meditative” element returns for a quiet ending. The emphasis on melody in this movement, and its subtle evocation of blues, make it a clear contrast to its companions: an interlude of rest and downtime after the upbeat opening and the hard-driving finale, marked Third Movement: 40% Swing. “[This movement] is for four-wheel-drives only,” says Adams, “a big perpetual-motion machine…. On modern MIDI sequencers the desired amount of swing can be adjusted with almost ridiculous accuracy. Forty percent provides a giddy, bouncy ride, somewhere between an Ives ragtime and a long rideout by the Goodman Orchestra ca. 1939.” There’s a kind of urban agitation to this movement; we could have left the desert for a busy city street. Or maybe it’s meant to convey a more challenging road, perhaps in the mountains, requiring four-wheel drive. The chordal piano texture is contrasted with scurrying motives in the violin, and both players are rendering intensely biting nuggets of sound. The rhythmic vitality is so strong you find you’re tapping your toes, prompted by the swing in the piano part (boogie-woogie?), or perhaps by the hint of bluegrass fiddling style in the violin.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

A Personal Statement

Notes by Jennifer Koh

The idea for this program has been living within me for several years. I believe that works of music, art, and culture are as much a creation of their time as of their individual creators. For me, the music that has been created in my lifetime is both a reflection of myself as a member of our society and the inspiration that shapes me as a musician.

I created this program as a reflection of my subjective response to external influences: in Jennifer Higdon’s String Poetic, written for me in 2006, the poetry she wrote as an inspiration point for each movement made me acutely aware of my own, somewhat shy, poetic impulses. John Adams’s Road Movies conjures up in sound the American landscape into which I was born and which, with its boundless dimensions, has always piqued my imagination. Lou Harrison’s Grand Duo was immediately attractive to me because it speaks in a voice that combines the Western tradition of my own background with the enticing strangeness of Asian traditional music. Although Carl Ruggles might not fit into this program chronologically, the beautiful, poetic underlay of Mood convinced me to include this incredible, unpolished jewel on my recording (the piece was posthumously assembled from Ruggles’s sketches). Here, to my mind, imperfection outshines perfection itself.

Album Details

Total Time: 73:45

Producer & Engineer: Judith Sherman

Assistant Engineer: Jeanne Velonis

Digital Editing: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover Photo: Fran Kaufman

Recorded: March 7-9, 2007, at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City.

Microphones: Schoeps MK2, Sonodore

© 2008 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 103