Store

2017 Grammy nominee – Best Chamber Music/Small Ensemble Performance

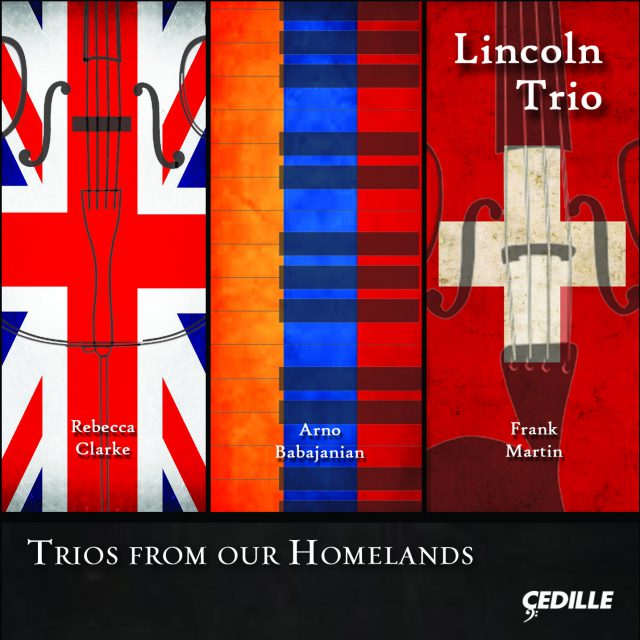

The Lincoln Trio is renowned for creating “worthwhile programs of serious classical music that are wholly winning and simply delightful” (ClassicsToday.com). For its newest Cedille Records album, “the brilliant Chicago-based Lincoln Trio” (WRTI-FM, Philadelphia) of violinist Desirée Ruhstrat, cellist David Cunliffe, and pianist Marta Aznavoorian has crafted a highly personal program of inventive 20th-century piano trios by composers from the individual players’ ancestral homelands of Switzerland, England, and Armenia, respectively.

A one-of-a-kind album, Trios From Our Homelands offers stellar performances of substantial works that many listeners will be discovering for the first time. The 1922 Piano Trio by England’s Rebecca Clarke brims with attractive melodies presented with virtuosity and musical ingenuity. Armenia’s Arno Babajanian, whom Mstislav Rostropovich called “a brilliant composer,” is represented by his passionate Piano Trio in F-Sharp Minor from 1952. Swiss composer Frank Martin wrote his tuneful Trio on Popular Irish Melodies, the best-known work on the album, in 1925.

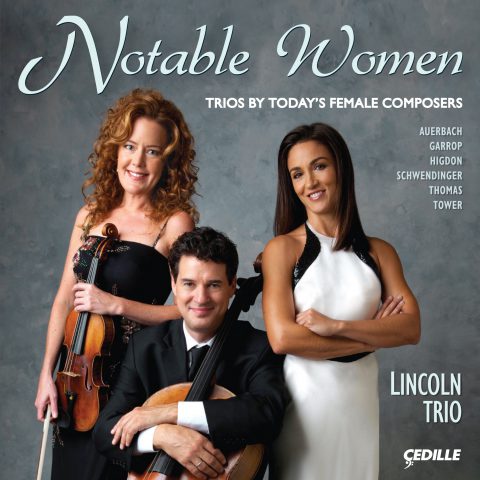

The Lincoln Trio made its full-length Cedille album debut with Notable Women, featuring works by Lera Auerbach, Stacy Garrop, Jennifer Higdon, Laura Elise Schwendinger, Augusta Read Thomas, and Joan Tower. Gramophone said, “The performances by the Lincoln Trio are models of vibrancy and control. The notables on this recording could hardly have better champions.” The Strad praised the ensemble’s “interpretative flair” and “supreme clarity of expression.” Cedille’s Turina: Chamber Music for Strings and Piano is an album on which “sensitive and polished readings by the Lincoln Trio and assisting musicians reveal what is best about this neglected repertory” (Chicago Tribune). The group also performed on the Grammy-nominated Naxos recording of James Whitbourn’s Annelies.

Listen to Steve Robinson’s interview

with the Lincoln Trio on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

REBECCA CLARKE (1886—1979)

Trio for violin, violoncello, and piano

ARNO BABAJANIAN (1921—1983)

Piano Trio in F-Sharp Minor

FRANK MARTIN (1890—1974)

Trio sur des mélodies populaires irlandaises

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletTrios From Our Homelands

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

Rebecca Clarke, Arno Babajanian, and Frank Martin could all be considered outsiders in the history of 20th-century classical music. Clarke wrote at a time when music composition was still very much a male-dominated field. Babajanian was an artistic hero in his native land but relatively unknown internationally. Martin grappled with conflicting stylistic influences for many years in the process of establishing his own voice.

The Lincoln Trio has chosen to highlight major works by these less celebrated composers to bring them some well deserved attention. Another reason they chose these particular composers was to highlight the countries of origin of the three members of the group: England, Armenia, and Switzerland. Thus the album title, Trios From Our Homelands.

Rebecca Clarke (1886–1979) began her musical studies on the violin but switched to the viola at the suggestion of her principal teacher at London’s Royal College of Music, the eminent composer-professor Sir Charles Villiers Stanford. She learned the viola from another eminent British musician, Lionel Tertis, and was soon supporting herself as a freelance orchestral musician. This was before World War I, when female professional musicians were scarce. It was during the war years that she first visited the U.S., which would eventually become her home.

Clarke had several encounters with Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, the famous patron of chamber music whose composition contests Clarke entered twice and narrowly lost twice: first for her Viola Sonata of 1919 and two years later for her Piano Trio. In 1919 she all-but-tied for the prize with Ernest Bloch. Mrs. Coolidge reportedly said, upon revealing the name of the runner-up, “You should have seen [the judges’] faces when they saw [the sonata] was written by a woman.” This was a phenomenon practically unheard-of in the early 1920s. The trio — Clarke once again took second place — was premiered in London in 1922 by violinist Marjorie Howard, Clarke’s cellist friend May Mukle, and pianist Myra Hess.

Clarke composed songs and a variety of chamber music, most of it featuring the viola. In her late 50s she married a former classmate from her Royal College days, pianist-composer James Friskin. In spite of his encouragement, she gradually abandoned her compositional career. She died in New York City at the age of 93. In 2000 the Rebecca Clarke Society was founded to promote her music.

Those first London listeners in 1922 heard a trio full of attractive melodies combined and presented in a context of virtuosity and musical ingenuity. The marking Moderato ma appassionato well characterizes the rhapsodic first movement, which begins with an emphatic piano passage. We next hear from the cello before all three instruments join together. The opening motto returns in various guises to unify the movement, which contains a second, more lyrical theme. The moods of agitation and peace alternate and often feature the violin and cello in close imitation. The ending is quiet, setting up the Andante molto semplice middle movement, which opens with a quiet, almost folk-like melody for violin and cello in imitation over subdued piano chords. The word “lullaby” has been applied to this movement; it could also be thought of as a song without words, which ends with a plaintive violin passage. The Allegro vigoroso finale, again aptly headed, is almost like a hoedown: the piano dominates the opening, soon joined by the violin in a kind of country-fiddling mode. The impression of a dance is inescapable in spite of the frequent shifts of meter. A big, passionate central section interrupts the dance, then a quieter portion leads back to it for a rousing conclusion.

The writing, noticeably virtuosic for all three players, includes some special string effects: contrasts between bowed and pizzicato playing, as well as some double-stops. The piano part features reiterated, powerful chords and rapid runs. The cello often plays in its high range (treble-clef territory), imparting a richness and poignancy to melodic figures that sound subtly different from the violin’s sonority when it plays in the same range.

Arno Babajanian (1921–1983) was a child prodigy from a musical family; his father was an accomplished player of Armenian folk instruments. The noted composer Aram Khachaturian, one of the most famous and influential of Armenian musicians, recommended that Babajanian enter the Yerevan Conservatory when he was still just a schoolkid. He later studied both piano and composition at the Moscow Conservatory, then returned to Yerevan to teach at that city’s conservatory, establishing his three-pronged career as a professor, pianist, and composer. He undertook a number of concert tours in the former Soviet Union while writing his Armenian Rhapsody, Poem-Rhapsody, a cello concerto for Mstislav Rostropovich, a variety of piano and chamber music, popular songs, and some film music. Rostropovich’s called him “a brilliant composer, fiery pianist, beloved neighbor, and devoted friend for many years — this for me was wonderful Arno Babajanian, who, despite his early death, made a significant contribution to the music of our time.”

Babajanian’s Heroic Ballade for piano and orchestra is often cited as one of his major creations, inspired by Armenian folk melodies and indebted to Rachmaninoff for its rich keyboard sonorities. Other influences on Babajanian’s music were the works of Khachaturian, Prokofiev, and Bartók (the last two, like him, notable pianists). His 1952 Piano Trio in F-Sharp Minor was premiered the following year with the composer at the piano joining violinist David Oistrakh and cellist Sergei Knushevitsky.

Babajanian’s debt to tradition is perhaps reflected in that his is the only work on this album with a key signature in its title. He begins in the stated F-sharp minor but wanders significantly from it over the course of the trio’s three movements. The first is an Allegro espressivo, preceded by a Largo introduction of major importance to the work, since the shape and intervals of its motive will recur and inform the themes and structures of the entire piece. The main portion of the movement begins with a cello solo. The second theme, projected by a piano solo, is more serene and diatonic; it also departs from the home key. An agitated section precedes a regular recapitulation. The coda is signaled by big forte piano chords. Pianissimo and fortissimo and all the dynamic grades in between bring out the espressivo in the movement heading.

In a lovely atmosphere of C major, the violin begins the Andante over a quiet piano accompaniment. The movement, virtually monothematic, continues with a solo-cello presentation of a folk-like melody over piano arpeggios. The texture becomes more chromatic and the mood more intense, with the two stringed instruments often playing in unison with octave (or more) separation. The violin, muted, recaps the opening, and the final passage is given to the piano, with a dynamic marking of ppp.

Back, at least briefly, in F-Sharp minor, the Allegro vivace finale is cast mostly in the unusual meter of 5/8, adding some irregular accents and rhythmic progressions to a highly energetic conclusion. Rapid, almost continuous piano chords contrast with the string lines, once again often in unison. The final passage has the tempo marking Maestoso (majestic) and we hear again the complete motto from the trio’s opening that has generated so much of what has come before. It gives way to a frenzy of final chords and runs, emphasized by the dynamic marking sf (sforzando), indicating particularly strong and sudden accents.

The best known trio on this album is the Martin, which occasionally appears on chamber-music programs and has been recorded several times. It’s still a work that should be played more often: a brief but unusual treatment of folk melodies in a concert-music format. Frank Martin (1890–1974) was born in Geneva, the son of a clergyman who didn’t particularly encourage his musical interests. Moving from Geneva to Zurich, Rome, and eventually Paris, Martin absorbed many musical influences: the works of Bach, the late-Romantic sounds of César Franck, American jazz, Far-Eastern sonorities, folk music, and the rhythmic theories of Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, the founder of the eurhythmics system of teaching music. An encounter with conductor Ernest Ansermet, who would later champion his music, introduced the young experimenter to the works of Debussy and Ravel. Martin would also become interested in Schoenberg’s twelve-tone method of composition, although he never adopted it. He eventually taught in both Switzerland and Germany, and in the 1940s emigrated to the Netherlands.

Martin made major contributions to the realm of sacred music in the form of his Mass for Double Choir and the oratorio In Terra Pax (Peace on Earth). These works reflect his deeply spiritual nature and his striving for the ideal, in both life and the world of art.

The Trio on Popular Irish Melodies, dates from 1925 and is considered one of his most important early compositions. It was commissioned by an amateur American musician who wanted a piece based on familiar Irish tunes. Martin instead sought out more obscure, and perhaps more authentic, Irish folk melodies in Paris’s largest library. The disappointed patron withdrew his commission, but fortunately Martin finished the trio anyway. Its aim is not to reproduce hummable songs, but rather to take the tunes as a starting point to experiment with expanding and re-combining them in a context that also has remarkable rhythmic interest.

So this isn’t Irish Night at the karaoke bar, or a jam session on St Patrick’s Day. The first movement is marked Allegro moderato – Allegro marcato, marcato meaning strongly-defined rhythm. The violin and cello get the first tune, a dance-like theme over subdued piano accompaniment. As the pace picks up, the piano becomes more prominent, introducing another melody. Then we hear from the cello, whose passage is picked up by the violin. In a progress of ever more complex rhythmic shifts, the movement proceeds to a big climax for all three players.

In the Adagio, the cello opens with a mournful minor-mode melody, the piano follows with a variant of it, and the violin enters with yet another variant. The texture is punctuated with off-beat piano chords. A livelier passage ensues, but the mood remains the same with the continuation of the minor mode, and its sense of sadness and yearning only intensifies as the Adagio progresses. A piano solo contains a new tune, or perhaps yet another variant of the opening. The strings have pizzicato passages before a recapitulation of the original melody from the cello, and an ending for the piano.

A new mood entirely takes over in the concluding Gigue. This is indeed an Irish jig, and it’s introduced by the violin, which sets the movement’s perpetual motion pace. The cello picks up the tune, followed by the piano, and the mode shifts brightly back to major. The rhythmic patterns are mostly triple, as we’d expect for a gigue, but they’re often interrupted with different patterns. The cello and piano are given a new, more chromatic tune that touches on several possible tonalities before the violin returns with the jig theme. The cello has a contrasting line beneath. In the coda, the piano gets its own version of the jig, before the strings return for all three players to share in the rousing conclusion.

Andrea Lamoreaux is Music Director of 98.7WFMT, Chicago’s Classical Experience.

Album Details

TT: (64:15)

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: August 24–26 and October 5, 2015 Anne & Howard Gottlieb Hall at the Merit School of Music, Chicago, Illinois

Publishers: CLARKE Trio for violin, violoncello, and piano ©1928 Boosey & Hawkes

BABAJANIAN Piano Trio in F-Sharp Minor ©1952 Edition Silvertrust

MARTIN Trio sur les mélodies populaires irlandaises ©1925 Verlaag Gebrüder Hug & Co.

Graphic Design: Nancy Bieschke

© 2016 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 165