Store

Store

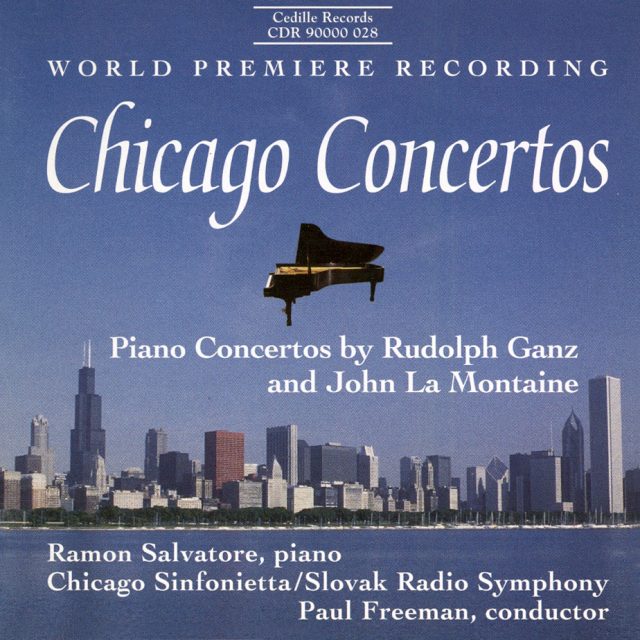

Chicago Concertos: Piano Concertos by Ganz and La Montaine

Ramon Salvatore, Rudolph Ganz, John La Montaine, Paul Freeman

The world premiere recordings of two contrasting piano concertos by major 20th-century American composers with ties to the Midwest present what presidential campaigners might call a bridge to the past and a bridge to the future. Here, listeners don’t have to choose between the two.

Ganz’s Romantically styled Piano Concerto in E-flat Major, Op. 32 (1940) and La Montaine’s jazzy, impressionistic Piano Concerto No. 4, Op. 59 (1989) are vastly different. Yet besides having spent significant periods of their lives in the Chicago area, the composers share the goal of writing “music that appeal to a wide audience, infusing their work with enough ingenuity and substance to satisfy the most discriminating performer,” writes Stephen C. Hillyer in the program notes.

Commissioned by the Chicago Symphony for its 50th anniversary, Ganz’s concerto, like the rest of his output, is “cosmopolitan, conservative, and — especially in the work at hand — uncommonly witty, as was the man himself,” Hillyer writes. Born in Switzerland, Ganz studied piano with Busoni in Berlin. He came to Chicago in 1901 and began a long association with the Chicago Musical College, including 25 years as its director (1929-1954). He was music director of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (1921-27) and led its first recordings for the Victor label. Ganz conducted the New York Philharmonic’s Young People’s Concerts and guest conducted the symphony orchestras of Los Angeles and Chicago.

Born in 1920 in Oak Park, Illinois, home of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “prairie style” architecture, La Montaine (who currently resides in Hollywood, CA), studied theory at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago and composition at Eastman with Howard Hanson. He also studied piano with Ganz for a short time. La Montaine played keyboard for the NBC Symphony during Toscanini’s last four seasons (1950-54).

“La Montaine’s Fourth Piano Concerto,” writes Hillyer, “is that rarity in this century (or any other for that matter): a listener-friendly work that immediately appeals with memorable tunes and catchy rhythms, yet grows increasingly impressive with each rehearing.” The work, commissioned for the Waterbury (Connecticut) Symphony’s 50th anniversary, received its world premiere in 1990.

A champion of neglected American piano music, pianist and teacher Ramon Salvatore has received praise for his groundbreaking concerts and recordings on Cedille and other labels. Sadly, this was Mr. Salvatore’s last recording: he died of cancer in 1996, at age 51. This recording is dedicated to his memory.

In a recent letter to Cedille Records, La Montaine says, “The world has lost a great pianist.” He writes that Mr. Salvatore’s recordings of his music “set a standard for all future performances . . . A composer cannot but be grateful to have such abilities lavished on his works.”

Preview Excerpts

RUDOLPH GANZ (1877-1972)

Piano Concerto in E-flat Major, Op. 32*

JOHN LA MONTAINE (1920–2013)

Piano Concerto No. 4, Op. 59*

Artists

1: with the Chicago Sinfonietta

5: with Slovak Radio Symphony

Program Notes

View Album BookletChicago Concertos

Notes by Stephen C. Hillyer

Though stylistically miles apart, the two concertos receiving their world premiere recordings on this CD are connected in several ways. Both composers spent significant periods of their lives in the Chicago area: John La Montaine while growing up in suburban Oak Park (he now resides in Hollywood, California). Rudolph Ganz during most of his last seven decades, as head of the piano department and, later, as president and president emeritus of Chicago Musical College. These multi-faceted musicians became formidable pianists. La Montaine, in fact, studied piano with Ganz for a short time during the Second World War while serving in the U.S. Navy. Both men became avid mountain climbers. The two composers also share the goal of writing music that appeals to a wide audience, infusing their work with enough ingenuity and substance to satisfy the most discriminating performer. But their differences are even more striking, particularly in how they develop musical ideas. Ganz is clearly a product of the nineteenth century, La Montaine of the twentieth. Ganz’s elaborately ornamented piano writing recalls Rachmaninov and Liszt, while La Montaine embraces a wide range of territory, from polytonality to pop.

Ganz: Concerto for Piano in E-flat major, Op. 32 (1940)

Rudolph Ganz (February 24, 1877 – August 2, 1972) was born in Zurich, Switzerland. He received his initial musical training at the Zurich Conservatory, and in 1899 traveled to Berlin to study piano with Ferruccio Busoni and composition with Heinrich Urban. Although Ganz had made public appearances as pianist and cellist as a child, his debut as a mature artist took place at a concert of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in December 1899, when he performed the Beethoven Emperor Concerto and Chopin E minor concerto. The following year he conducted the Berliners in his own first Symphony.

In 1900, Ganz came to America, and from 1901 to 1905 taught piano at the Chicago Musical College, where he would return as director from 1929 to 1954. After 1905, he made concert tours in Europe and the United States. In 1921 he became music director of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, where he remained until 1927, having led its first recordings for the Victor label.

From 1938 to 1949 Ganz conducted the New York Philharmonic’s Young People’s Concerts and led the orchestra at Lewsohn Stadium during the summer season. He also presided over the San Francisco Young People’s Concerts at this time and guest -conducted the symphony orchestras of Chicago (where he also frequently appeared as piano soloist), Los Angeles, and Denver.

Throughout this remarkably diverse and fruitful career, Ganz remained a tireless champion of contemporary music, which in his case meant anything from Saint-Saens, Busoni, or Griffes in the early decades, to Bartok, Webern, and Cage Lateron. Ravel dedicated his most difficult piano piece to Ganz, the “Scarbo” movement form Gaspard de la nuit. Griffes did the same with his most popular work, The White Peacock.

Rudolph Ganz’s own musical idiom is cosmopolitan, conservative, and – especially in the work at hand – uncommonly witty, as was the man himself. The most famous example of the Ganz wit occurred in 1906 when he helped his friend Artur Rubinstein, then embarked on his first American tour, reply to a lady in Washington who had confused the young Pole with the venerable Russian composer Anton Rubinstein. She had requested that Kammenoi-Ostrow be included in his recital program. Since Rubinstein did not feel up to corresponding in English at that time, Ganz offered to reply for him. The Washington lady received the following cordial note:

Dear Madame:

Thank you for your kind letter. I would be delighted to play for you my celebrated Kammenoi Osrow. Unfortunately, it will not be possible. I am dead.

Sincerely yours,

A. Rubinstein

The Piano Concerto in E-flat was one of several works commissioned by the Chicago Symphony to celebrate it fiftieth anniversary; the others included Stravinsky’s Symphony in C and compositions by Carpenter, Casella Gliere, Harris, Kodaly, Miaskovsky, Milhaud, and Walton. The premiere took place in Orchestra Hall on February 20, 1941, wit Ganz as soloist. Notable subsequent performances were given by Mary Sauer and the Chicago Symphony under Jean Martinon in November 1968 (as part of a concert celebrating the Illinois Sesquicentennial), Sheldon Shkolnik and the St. Louis Symphony under Leonard Slatkin in July 1971 (to honor the fiftieth anniversary of Ganz’s appointment as conductor of that orchestra), and on February 26, 1996, Ramon Salvatore and the Chicago Sinfonietta under Paul Freeman, in observance of “Rudolph Ganz Day in Illinois” (February 24 – Ganz’s birthday – officially so designated “in perpetuity” by Gov. Otto Kerner in 1967). The composer supplied the following program notes for the world premiere:

Recalling my first appearances with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra [in the Auditorium theatre] in the Fall of 1903 under Theodore Thomas, and realizing that I have had ten subsequent artistic co-operations, or may I say music-makings with Theodore Thomas’ successor my good friend, Dr. Frederick Stock, I feel most happy that he should have asked me to write a work for piano and orchestra as my contribution to the [Golden] Jubilee Season.

Here it is: A Concerto in four movements, the titles of the different parts being: I. March-like; II. Songlike: III Dance -like; IV. Finale (to avoid saying finale-like).

The principal theme of the March movement is greatly developed in the middle section of the piece and for this reason does not appear in the Recapitulation. But it serves again as a final coda. The second theme (lyrical) contrasts the rhythmical figure of the March-theme. It is introduced by the piano and then repeated by the violoncellos in inverted form. A short coda leads into the development during which section the March-idea appears in both augmented and contracted form. The movement being in E-flat, the keys presenting the second theme and its repetition are respectively B-flat and G major. Dissonance, if any, is not for the purpose of appearing daring or particularly progressive. It is logically developed and should add spice to the otherwise plain, straightforward musical expression.

The second movement permits the solo instruments to introduce the principal song-like idea which the string orchestra and a few single wind instruments continue tin the same mood. A middle section is based upon a rhythmical figure taken from the first four notes of the main theme. Elflike figures chat charmingly (or at least are supposed to) with the sterner attitude of the orchestra. A somewhat altered repetition of this part leads into a climax, during which different instruments boldly announce the return of the first subject in greatly augmented fashion. The abrupt ending of the climax is followed by a short cadenza which leads into the recapitulation of the main theme, again in g major, but played by woodwinds. However, the solo instrument picks up the melody after four bars. While the orchestra repeats its section of the song-like continuation, the piano decorates the picture with scale-like patterns in fast sixteenth triplets whereas the patterns during the earlier presentation were in sixteenths only. At the conclusion of the movement of the elf-like charm-calls reappear, and are imitated by the hesitatingly mocking celesta. [A glockenspiel is use don this recording.] Then the sounds die down and quiet reigns.

The Scherzo is some kind of a patriotic outburst, some rather odd ode to the revered State of Illinois, and to Secretary Edward J. Hughes in particular. The accompaniment patterns of the beginning and of the middle section are musicalized Illinois automobile licenses, 280893 being my 1940 (in A minor) and 501127 being my 1941 (in A major) license. They serve as ostinati for nearly the entire Scherzo. It was my intention to use Dr. Stock’s 1940 license as the trio pattern. My request for his important information was heeded too late for incorporation. The Scherzo was practically finished when the straggling number arrived. But Dr. Stock’s license number is heard at the end of the movement as a longing, sad little viola solo – the latecomer’s fate.

The Finale (in C minor) does not call for any particular description, the themes being very outspoken. The principal subject is rhythmical, the contrasting second theme necessarily lyrical. The development is climaxed by an augmentation of the second subject (four horns) accompanied by a rhythmical pattern-dialogue between the piano and the orchestra. A long crescendo built upon the first three notes of the opening bars of the concerto brings back the March-theme of the first movement in unison of all instruments including the solo piano. A final coda-Scherzo (6-8) is made up of the March-like subject (piano) and the second Finale Theme (pizzicato strings). The first bar of the concerto has the last word.

La Montaine: Piano Concerto No. 4, Op. 59 (1989)

John La Montaine was born March 17, 1920 in Oak Park, Illinois, and studied theory with Stella Roberts at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago. At the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, he studied composition with Bernard Rogers and Howard Hanson and later worked with Bernard Wagenaar at Juilliard and Nadia Bulanger at the American Academy in Fontainebleau, near Paris. During Arturo Toscanini’s last four seasons with the NBC Symphony (1950-54), La Montaine served as the orchestra’s keyboard player, a stint immortalized in celebrated recordings of La Mer and Iberia in which the young composer can be heard playing celesta. La Montaine has been honored by two Guggenheim fellowships, commissions from the Ford and Koussevitzky foundations, and a season as composer-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome. His compositions range from symphonic to chamber music, from ballet to opera, from medieval to romantic to dodecaphonic and serial, to hymn and folk song. Two major song cycles for soprano and orchestra, Song of the Rose of Sharon and Fragments from the Song of Songs, have been widely performed by Leontyne Price, Adele Addison, Eleanor Steber, and Jessye Norman. His First Piano Concerto, given its world premiere by Jorge Bolet and the National Symphony under Howard Mitchell in November 1958, won the Pulitzer Prize the following year, and in subsequent seasons was presented in Boston, Cincinnati, San Francisco, and elsewhere. His Overture: From Sea to Shining Sea was the first work commissioned for a U.S. presidential inauguration, that of John F. Kennedy.

La Montaine’s music has won the admiration of critics and the affection of a wide public. But it is not represented on compact disc to the extent befitting a composer of his stature, a situation which fortunately has taken a turn for he better in recent years. 1992 brought Ramon Salvatrore’s widely-praised “Music in the American Grain” CD (Cedille CDR 90000 010), which contained the early Piano sonata; this year has brought the Flute Concerto (Premier PR 1045), and at this wrting, Citadel Records plans to reissue on CD the First Piano Concerto (formerly on CR1). Now Cedille offers the Fourth. One hopes that Birds of Paradise will eventually reappear on Mercury Living Presence. Wilderness Journal, a symphony for bass-baritone, organ, and orchestra commissioned for the opening of Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., was recently released on CD and cassette by Fredonia Discs, the composer’s own label (3947 Fredonia Drive, Hollywood, CA 90068).

Monrle Levin’s essay “Music in the American Grain,” written for the eponymous CD mentioned above, points out that La Montaine, like Robert Palmer and Hunter Johnson relates more to the “Harris” half of the “Copland-Harris’ School:

All three were, like Roy Harris, alumni of Howard Hanson’s Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, where an inland variety of modernism prevailed. All tended to follow Harris (and Bela Bartok) in pursuing the elusive spirit of native folksong rather than quoting it directly…There is joy and triumph in this music of Inner America, but little of Copland’s urbane wit and irony.

La Montaine feels that all of his works, however diverse, are related one to another, and there are frequent references to material that appears elsewhere in his compositions.

La Montaine’s fourth Piano Concerto is that rarity in this century (or any other, for that matter): a listener-friendly work that immediately appeals with memorable tunes and catchy rhythms, yet grows increasingly impressive with each rehearing, revealing skillful workmanship and a deep-seated musical logic. Commissioned for the Waterbury (Connecticut) Symphony’s fiftieth anniversary, the concerto received its world premiere in April 1990 from that orchestra, with the composer as soloist, under the direction of Frank Brieff, (A fellow alumnus of the NBC Symphony, Brieff served as principal violist under Toscanini from 1948 to 1952.) Ramon Salvatore gave the Midwest premiere in October 1993 in Palatine, Illinois, with the Harper Symphony Orchestra led by Frank Winkler.

The concerto is in three movements. IN the composer’s note prefacing the score, La Montaine writes that the Fourth Concerto is “significantly based on three of my song settings: a popular song, a sonnet, and an incantation.”

The first movement opens with a slow, mysterious introduction scored for muted brass, suspended cymbals, crotales, and strings. The piano soloist then weaves a series of ascending polytonal arpeggios derived from this introduction, a further variant of which will be heard in a cadenza-like passage toward the end of the movement. Both contrasting themes in this sonata-allegro movement are in F minor and are sometimes combined or interwoven. Theme A, which stems from a song La Montaine wrote for and African-American pop group, is harmonized by a series of descending parallel triads. Theme B comprises a syncopated staccato figure introduced by low woodwinds in canon. Following a short cadenza-like statement by the soloist marked quasi recitative, piano and orchestra bring the movement to a decisive close.

Marked “Gently flowing, soaringly lyrical,” the haunting theme of the second hovers between E major and the relative-minor key of C-sharp and also refers back to earlier work. La Montaine originally set the fifth (“Shall I compare thee”) of his Six Sonnets of Shakespeare to this eminently singable tune, a melody which later appeared in his solo piano piece A Summer’s Day. In the concertante setting that concerns us here, the expansive theme builds to a grandiose climax, the movement eventually dying down to a poco piu lento close.

The third movement begins, like the first, with a quiet, mysterious introduction (muted horns, strings, timpani). A sudden crescendo brings the music to a rapid boil, preparing the soloist’s dramatic entrance. The two segment principal theme (F – B-flat – B natural, followed by an insistent eight-note motif) recurs several times during the course of the movement, rondo fashion. True to form, La Montaine had used this same motif earlier in his song Invocation and in the Incantation for Jazz Band. A reflective section follows, leading to a brilliant cadenza. The coda recalls theme A from the first movement, after which is heard a powerful ritenuto statement of the repeated eight-note motif, slowed now to quarter-note triplets, and leading to an affirmative, resounding close.

Stephen C. Hillyer, a publications editor for Northwestern University, attended Chicago Musical College during he 1960s. For many years he was president of The Fritz Reiner Society (which is no longer active) and editor of its magazine, The Podium. Mr. Hillyer’s discography of French conductor-composer Jean Martinon was privately published in 1995.

Album Details

Total Time: 54:15

Recorded: February 26 & 27, 1995 in Bratislava and February 27, 1996 in Lund Auditorium, Rosary College, River Forest,

Illinois Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone Cover

Photography: Erik S. Lieber

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Stephen C. Hillyer

© 1996 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 028