| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

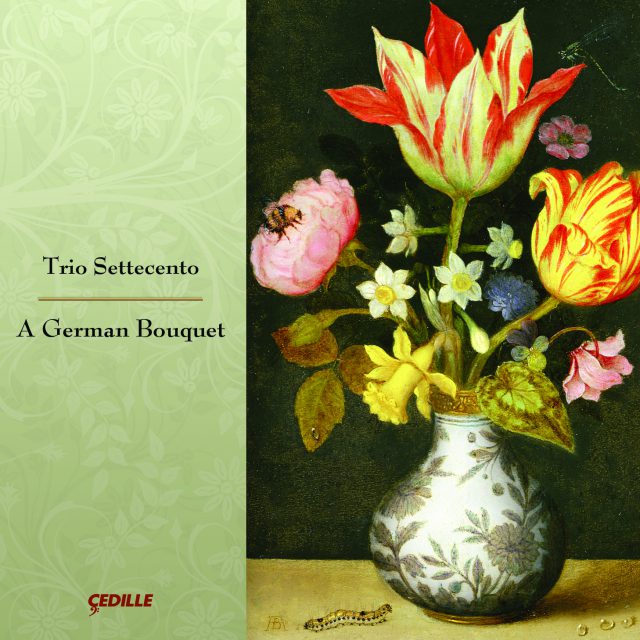

Chicago-based period-instrument ensemble Trio Settecento (1700s Trio) performs a colorful cluster of Baroque sonatas on A German Bouquet, the second in a planned series of four CDs illustrating the character and complexion of the era’s music as it developed in various regions of Europe.

On A German Bouquet, the trio of violinist Rachel Barton Pine, viola da gamba player and ‘cellist John Mark Rozendaal, and harpsichordist and organist David Schrader presents a program that goes beyond Bach and Buxtehude. While the CD includes works by those two giants of the German Baroque, it also offers rarely heard repertoire by Johann Schop, Johann Heinrich Schmelzer, Georg Muffat, Johann Philipp Krieger, Philipp Heinrich Erlebach, and Johann Georg Pisendel, some of whom were also among the greatest German violinists of the era.

Preview Excerpts

JOHANN SCHOP (d. 1667)

JOHANN HEINRICH SCHMELZER (C. 1620–1680)

GEORG MUFFAT (1653–1704)

Sonata in D major

JOHANN PHILIPP KRIEGER (1649–1725)

Sonata in D Minor Op. 2, No. 2

DIETRICH BUXTEHUDE (1637–1707)

Sonata in C major, Op. 1, No. 5

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)

PHILIPP HEINRICH ERLEBACH (1657-1714)

Sonata No. 3 in A Major

JOHANN GEORG PISENDEL (1687–1755)

Sonata in D Major

J.S. BACH

Sonata in E Minor, BWV 1023

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletA German Bouquet

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

All of the nations of Northern Europe, where the winters are dark and pork fat is a foundation of the cuisine, share the ideal of gemütlichkeit (roughly, “coziness”): an idea of pleasant domesticity that combines modesty with luxury. The most tender personal thoughts and relationships are given play in the context of intimate interior spaces and occasions are lovingly crafted for the personal satisfaction of individuals and small circles of friends and relations. Ostentation plays no part. Thus, while the International High Baroque style formulated in the courts of Italy, France, Spain, and England strove for limitless glory and grandeur, producing palaces, cathedrals, and operas at a level of opulence that threatened to bankrupt nations, musicians employed by the princes of the Holy Roman Empire lavished some of their most loving attentions on chamber music: works of modest scale, requiring small forces to perform, yet offering listeners precious moments of emotional transport, insight, and catharsis. This music endures as one of the most potent expressions of the spirit of the land of denker und dichter — thinkers and poets.

The composers represented on this program worked at churches and courts in Hamburg, Lübeck, Leipzig, Vienna, Rudolstadt, Dresden, and Weissenfels, to name only a few of the German musical centers they embellished with their compositions. Each of these places had its own peculiar indigenous qualities. The cultural productions of each were shaped by different ways of assimilating the various cross-currents of Italian, French, and English cultures, Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Pietism. Therefore, each of the works on this program has its own distinct terroir, every one delicious and as different from the next as Gewürztraminer is from Riesling.

In the early years of the seventeenth century, many English musicians worked in Germany and Denmark. Hence, the German virtuoso violinist and composer Johann Schop (d. 1667) worked closely with English viol player and composer William Brade in Copenhagen and Hamburg. Several of Schop’s surviving violin compositions are variation pieces in the English “divisions” style and based on English sources. “Nobelman,” found in the 1646 Amsterdam anthology T’Uitnement Kabinet, appears to be such a piece, although its source is unknown.

Four of the sonatas on this program (Schmelzer, Krieger, Buxtehude, and Erlebach) are trios scored for violin, bass viola da gamba, and keyboard. This variation on the conventional trio sonata scoring (two violins or equal treble instruments with basso continuo) enjoyed a period of popularity in German-speaking areas, and also existed in England, France, and Italy.

Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (c. 1620–1680), also a renowned violinist, was employed for many years at the Imperial court in Vienna. Here the primary influence on instrumental chamber music was Italian, notably through the presence of violinist/composers Antonio Bertali and Giovanni Battista Buonamente. Schmelzer’s D-minor sonata, originally published in the 1659 collection Duodarum selectarum sonatarum, bears striking resemblance to the sonatas of Biagio Marini and Dario Castello in the same key (recorded on Trio Settecento’s previous CD, An Italian Sojourn).

The cosmopolitan career of Georg Muffat (1653–1704) took him from his birthplace in Savoy to all of the continent’s most brilliant capitals, including extended stays in Paris where he learned the Lullian orchestral style, and Rome where he entered the circle of Arcangelo Corelli. He is best remembered for his publications of orchestral suites and concerti, which disseminated the styles of Lully and Corelli in Germany. This violin sonata is Muffat’s earliest surviving work, composed in Prague in 1677. Muffat, having spent the previous year in Vienna, would have been fresh from an encounter with Heinrich Biber, an original virtuoso whose violin compositions are notable for their colorful programmatic content. The Muffat sonata is sui generis, unlike any other piece of its period (or any other). The single unbroken sequence of fast and slow sections (a structure recalling the early Italian sonata) tells a dramatic story deploying extravagant harmonic excursions in the manner of the German stylus phantasticus. The strikingly noble, serene opening melody anticipates the most memorable Apollonian creations of Corelli and Handel. In the middle sections, this poise gives way to virtuosic frenzies (possibly inspired by Biber) featuring the type of string-crossing athletics that Corelli eschewed.

Over the course of a brilliant international career, Johann Philipp Krieger (1649– 1725) traveled to many of the German courts and Italy before settling at Weissenfels, where he served as Kapellmeister. In Italy, Krieger studied composition with Johann Rosenmüller, Antonio Maria Abbatini, and Bernardo Pasquini. Krieger’s twelve sonatas for violin, viola da gamba, and basso continuo (1693) may have been inspired by Rosenmüller’s identically-scored compositions. The D-Minor sonata opens with an Italianate sequence of slow and fast passages. The stately aria with variations that follows is based on a chorale-like theme clearly evoking the composer’s Lutheran roots.

Dietrich Buxtehude (1637–1707) served as organist, secretary, treasurer, and business manager of the Marienkirche (Church of Mary) at Lübeck from 1668 until his death. Although his musical duties involved in this official position were limited to the provision of organ music for church services, Buxtehude’s musical career encompassed far more varied activities. His vocal works survive mostly in manuscripts preserved in the Düben collection at Upsala. The high quality of this music suggests that the loss of his renowned Abendmusiken oratorios is a great one. Buxtehude also maintained close relationships with a number of musical friends at Hamburg, including Johann Theile and Adam Reinken. This sophisticated milieu included virtuosic instrumentalists and may have inspired the fourteen brilliant and witty sonatas Buxtehude published as Opus 1 and Opus 2 in 1694 and 1696, respectively. Surprisingly, the formats of Buxtehude’s sonatas do not hew to the Corellian models already well established by this time. In fact, their multiplicity of forms, including fugal movements, dance forms, ostinato variations, and quasi-improvisatory (stylus phantasticus) passages arranged in richly varied sequences recalls the Italian sonatas of earlier generations. The C-Major variation, and an adagio in the fantastic style smoothly transitioning into a final fugato.

Philipp Heinrich Erlebach (1657–1714) served as Kapellmeister at the court of Count Albert Anton von Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt at Rudolstadt from 1681 until his death. Erlebach’s surviving works include church cantatas, organ music, a set of orchestral suites in the French manner, and an outstanding song collection which apparently includes extracts from lost theater works. His six sonatas scored for violin, viola da gamba, and continuo (1694) all share the same format. In each, an opening sequence of slow and fast sections in the manner of an Italian sonata is followed by a suite of dances in the French style. Several of these sonatas call for alterative tunings of the violin (scordatura). In the Sonata Terza the violin is tuned a-e’-a’-e”, producing a brilliant and sonorous effect. This sonata is unique in the set for the inclusion of a lengthy and thrilling chaconne followed by a poignant final adagio.

Johann Georg Pisendel (1687–1755) was the finest German violinist of his generation. From 1712 he was a member of the court orchestra at Dresden, and from 1728 concertmaster of that prestigious ensemble. Pisendel’s path crossed that of J.S. Bach more than once: in 1709 en route to Leipzig, Pisendel visited Bach in Weimar; and Bach would certainly have heard Pisendel perform in the course of his regular visits to Dresden to hear the opera. Pisendel traveled extensively with his employer, Dresden’s electoral prince, including a lengthy trip to Italy. In 1716, Pisendel spent six months in Venice where he studied with and befriended Antonio Vivaldi. The Violin Sonata in D Major appears to date from this time and falls neatly into the three-movement format of a Vivaldi concerto. Pisendel’s Northern roots show clearly, however, in the third movement, where a gracious, galant, minuet-like subject evolves into a dramatic stürm und drang episode. The sonata, with its extraordinarily advanced technical demands, is closely related to Pisendel’s Concerto in D Major. The later concerto appears to be a revision of the sonata, not (as one might guess) the other way ’round.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) is represented by two works of widely different character. The Fugue in G Minor is the earliest-surviving example of J.S. Bach’s chamber music. Composed before 1712, it demonstrates the composer’s genre-bending creativity. The fugue as developed by the Northern German organ school is here adapted to the medium of solo violin with basso continuo accompaniment. The transfer of idiom results in formidable technical challenges for the performers, an effect Bach seems to have relished. The Violin Sonata in E Minor, composed in Leipzig after 1723, shows the influence of Bach’s encounter with the French instrumental style during his years at Cöthen. The Allemande and Gigue recall François Couperin’s ideal of les goûts réunis (the styles reunited) as the master deploys Italianate virtuosity and Germanic harmonic invention to elevate two gracious French dance forms to a summit of poignant expressivity. It is moving to reflect that the opening movement’s homage to Corelli comes from the pen of one who, unlike so many other German masters of the violin sonata (Handel, Pisendel, Muffat, Krieger), never visited Italy, in fact never left his native Germany.

Album Details

Total Time: 78:30

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Art Direction: Adam Fleishman – www.adamfleishman.com

Cover Painting: Still Life with a Wan’li Vase of Flowers (oil on copper), Bosschaert, Ambrosius the Elder (1573- 1621) – Private Collection – Johnny Van Haeften Ltd., London – The Bridgeman Art Library

Recorded June 16, 17, 19, 23, and 24, 2008 in Nichols Hall at the Music Institute of Chicago, Evanston, Illinois

Instruments:

Violin: Nicola Gagliano, 1770, in original, unaltered condition

Violin Strings: Damian Dlugolecki

Violin Bows: Harry Grabenstein, replica of early 17th Century model (Schop and Schmelzer); Louis Begin, replica of 18th Century model (rest of program)

Bass Viola da Gamba: William Turner, London, 1650

Cello: Unknown Tyrolean maker, 18th century (Piesendel)

Viola da Gamba and Cello Bow: Julian Clarke

Harpsichord: Willard Martin, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1997. Single-manual instrument after a concept by Marin Mersenne (1617), strung throughout in brass wire with a range of GG-d3

Positiv Organ: Gerrit Klop, Netherlands (Schmelzer, Krieger, Bach Fugue, Erlebach I and VI)

Tuning: Unequal temperament by David Schrader, based on Werckmeister III.

©2009 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 114