Store

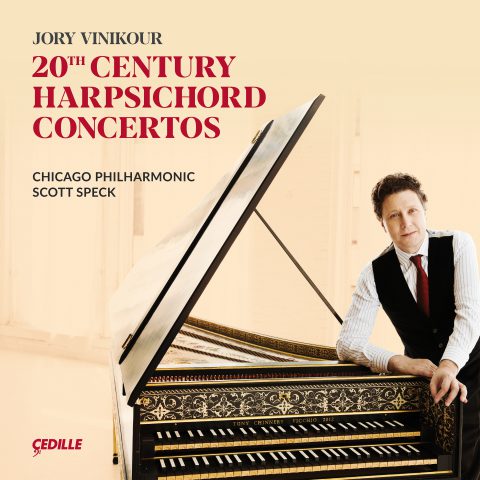

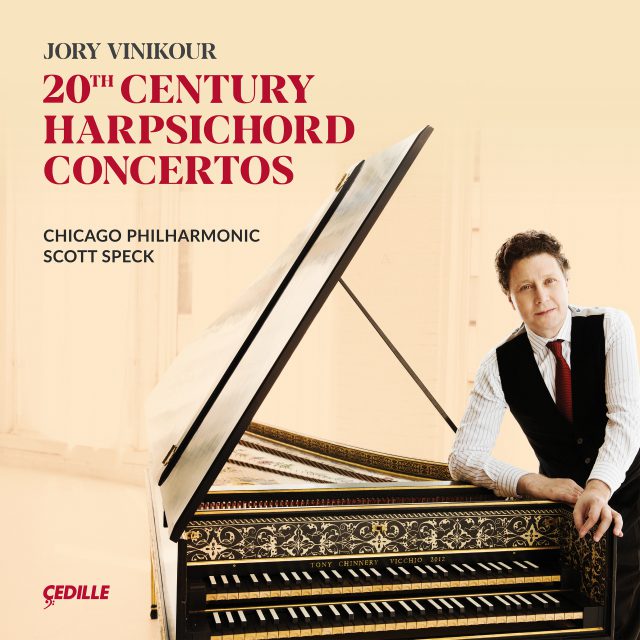

Two-time Grammy Award-nominated harpsichordist Jory Vinikour joins the Chicago Philharmonic, “one of the country’s finest symphonic orchestras” (Chicago Tribune), and its artistic director Scott Speck in a program of 20th-century harpsichord concertos spanning more than six decades.

The album includes the world premiere album release of Ned Rorem’s neoclassical 1946 Concertino da Camera, which the composer has called a “perfect recording.” The disc also offers Czech composer Viktor Kalabis’s intensely personal 1975 Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings and music by two English composers: Michael Nyman’s thrilling 1995 Concerto for Amplified Harpsichord and English composer Walter Leigh’s poetic 1934 Concertino.

Vinikour received Grammy nominations for Best Solo Instrumental Recording for his 2013 album of modern American music for harpsichord and his 2012 release of Rameau’s complete harpsichord works. BBC Music Magazine praised his “stylish playing, executed with a sensitive and easy touch.” Gramophone said, “Vinikour’s performances are so buoyant, glistening or noble that you’ll find yourself glued to your speakers (or headphones).”

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Jory Vinikour on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

WALTER LEIGH (1905-1942)

Concertino for Harpsichord and Strings

NED ROREM (1923–2022)

Concertino da Camera

VIKTOR KALABIS (1923-2006)

Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings, Op. 42

MICHAEL NYMAN (b. 1944)

Concerto for Amplified Harpsichord and Strings

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album Booklet20th Century Harpsichord Concertos

Notes by Jory Vinikour

Thanks to the talent and passion of performers such as Wanda Landowska and Violet Gordon-Woodhouse, the harpsichord began to reappear in Europe’s musical world in the first decades of the 20th century. Prominent composers, among them Francis Poulenc and Manuel de Falla, composed concerti for this newly rediscovered instrument. Manuel de Falla first featured the harpsichord in his puppet opera, El ratablo de maese Pedro, beginning its composition in 1919, with its premiere in 1923. He followed this work with his Harpsichord Concerto, premiered in 1926. Both works were intended for the Polish harpsichordist/pianist Wanda Landowska. Falla realized that the harpsichord was easily overpowered when in competition with larger instrumental forces; thus his concerto sets the harpsichord against a quintet composed of violin, cello, flute, oboe, and clarinet. Poulenc’s Concert Champêtre (also dedicated to Landowska), premiered in 1929, pits the harpsichord against a full symphony orchestra, creating considerable balance issues (which can be at least partially resolved with amplification).

The works featured on this recording span a period of more than 60 years, from Walter Leigh’s poetic Concertino for harpsichord and strings, premiered in 1934, to Michael Nyman’s thrilling and electric Concerto for Amplified Harpsichord and Strings, premiered in 1995. I have chosen to perform all of these works on so-called historic copies — i.e., harpsichords conceived and constructed after Baroque models. This choice was partially based on preference. The richer sound of such instruments is, in my opinion, better suited to recording.

In 1934, the promising young English composer Walter Leigh composed his charming, brief Concertino for Harpsichord and String Orchestra. Although the work was premiered with a piano soloist, the solo keyboard part fits the harpsichord’s idiom impeccably. I have performed this work on numerous occasions, generally directing from the keyboard(s), including two performances with Baroque strings (which works astoundingly well). Leigh’s early death in 1942 deprived England of one of its most gifted composers.

About the work, eminent expert on 20th-century harpsichord music (and harpsichordists) Robert Tifft says:

With its immediately appealing melodies, concise structure, and idiomatic writing, English composer Walter Leigh’s Concertino for Harpsichord and String Orchestra proves to be a persuasive introduction to the world of contemporary harpsichord music for many listeners.

Leigh was born in Wimbledon on June 22, 1905. His musical education began with his mother and continued with organist and composer Harold Darke. He graduated from Christ’s College, Cambridge in 1926 and from 1927–1929 studied composition with Paul Hindemith at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik. From 1931 he worked as a freelance composer in London, writing primarily for the stage and films, his greatest success being his 1932 comic opera Jolly Roger. Leigh shared Hindemith’s concern for practical music-making, and this is exemplified in his songs, chamber music, and compositions for amateur orchestra. During World War II he served as a trooper with the Royal Armoured Corps and was killed in action near Tobruk, Libya on June 12, 1942.

Leigh’s Concertino, composed in 1934 for Herr und Frau Hilmer Höckner, could indeed be defined as practical music in the best sense. The composition’s clarity, relative simplicity, traditional structure and scoring, along with a duration reminiscent of a typical small-scale baroque concerto, make it nearly a textbook example of neo-classical style. From the propulsive first measures of the opening Allegro, the harpsichord leads the way with thematic material upon which the orchestra comments and reinforces. An extended cadenza-like passage for the soloist occupies nearly a third of the movement’s length. The nostalgic central Andante opens with the unaccompanied soloist introducing a sighing theme of particularly English character. As the strings appropriate the melody, arpeggiated passages for harpsichord effectively contrast with the orchestra and exploit the instrument’s sonority. The finale, a rousing gigue-like Allegro vivace, brings the work to an all-too-early conclusion.

Leigh’s Concertino is now the most recognized of his compositions and was first recorded in 1946 by pianist Kathleen Long. Subsequent harpsichord recordings include those by Neville Dilkes, George Malcolm, Trevor Pinnock, and Colin Tilney.

In 1946, only 12 years after the composition of Leigh’s Concertino, legendary American composer Ned Rorem, all of 23 years old, wrote his Concertino de Camera. The work went unperformed until a 1993 performance at the University of Minnesota, under Alexander Platt’s direction. This album marks the first professional recording of this charming work. From this performer’s viewpoint, Rorem’s great fluency in keyboard writing, as well as his distinctive harmonic language with its use of gently extended tonality, are already very much in evidence. The small ensemble of mixed solo strings and winds features a solo cornet, perfectly juxtaposed against the virtuosic keyboard part.

The first movement (Allegro non troppo), a cheerful toccata, features an extended cadenza for the harpsichord — Ned Rorem meets Scarlatti! — with exuberant (and challenging) cross-hand writing. In the second movement (Molto moderato), after introducing the plaintive theme, the harpsichord’s complex filigree accompanies the gently melancholic melodic writing shared throughout the instrumental ensemble. The reel-like third movement (Presto) in a lively 6/8 demands great virtuosity from all players and brings the Concertino to a brilliant end.

Now, 73 years later, Ned Rorem (age 95) is the doyen of American music. Many of his wonderful songs for voice and piano were part of my earliest classical musical experiences, and to me seem an integral part of the American musical landscape. I was delighted to record his solo harpsichord work, Spiders, written for Igor Kipnis in 1968, on Toccatas, my 2013 album of American 20th-century harpsichord music, (Sono Luminus).

Of the Concertino da Camera, Mr. Rorem wrote in 2019:

In the summer of 1946 in Chicago, my friend Danny Pinkham taught me as much as I still know about the harpsichord. I was 22 and immediately wrote this Concertino Da Camera for harpsichord and seven instruments. It was consigned to a trunk, never to be heard and I left for France, sometime after that.

But now, some 70 years later, the renowned harpsichordist Jory Vinikour has brought the piece to light — found in the Ned Rorem Archives at the Music Division of the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. — and has performed and recorded it.

I was moved on hearing the piece — for the first time! Thank you to Jory Vinikour for this perfect recording.

Another formative figure in the revival of the harpsichord — and an altogether remarkable figure in the post WWII classical music world — was the Czech harpsichordist, Zuzana Růžičková (1927–2017). Certainly the most prominent harpsichordist in Eastern Europe, Růžičková survived internment in three Nazi death camps, and maintaining her strong anti-communist beliefs in communist Czechoslovakia, was still able to perform throughout the world, leaving many recordings. She married composer Viktor Kalabis in 1952 and he wrote numerous pieces for her.

In my own musical journey, I was privileged to meet Mme. Růžičková in 1994 in Prague, when she chaired the jury of the Prague Spring International Music Competition — the first year that harpsichord was featured at this competition. At that time, I remember well her kindness and seriousness of purpose. One year later, when I came again to Prague, I was invited, with my father, to have tea with Zuzana and Viktor at their beautiful apartment. Viktor had a special playfulness behind his serious demeanor, and Zuzana was imbued with great warmth, and a very gentle humor.

I had performed Kalabis’s Preludio, Aria e Toccata, “I casi di Sisyphos” as part of the Prague competition. I also performed his Aquarelles several times in recital. Zuzana spoke to me of the Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings, but the opportunity to perform it never arose. Many years later, when I was preparing the concept for this album, I reached out to inform her that I would record the Concerto. Some weeks later, I received a touching hand-written letter from her and am grateful for the support of the Viktor Kalabis and Zuzana Růžičková Foundation, who helped make this recording possible.

From my standpoint as a harpsichordist, it is difficult to imagine a work, distinctly a product of the 20th-century though it is, fitting the harpsichord so perfectly. Keyboard textures are expertly balanced, avoiding heaviness. The string writing is masterful and allows the harpsichord to shine through at all moments.

Robert Tifft, who also counted Viktor and Zuzana among his friends, writes of the Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings, opus 46:

The familiar three-movement structure and traditional scoring of the Concerto for Harpsichord and String Orchestra, Op. 42 by Czech composer Viktor Kalabis may suggest a neo-classical composition along the lines of Leigh’s concertino, but here one finds an uncompromising work of intensely personal expression.

Kalabis was born on February 27, 1923 in Červený Kostelec, a small town in Eastern Bohemia. He gravitated toward music as a child, displaying promise as a pianist. Poor eyesight saved him from conscription by Nazi occupiers during World War II, and he was instead sent to work in an aircraft components factory. After the war, he read musicology, aesthetics, philosophy, and psychology at Charles University and studied composition with Emil Hlobil and Jaroslav Řídký at the Prague Conservatory and Academy of Performing Arts. When the communists seized power in 1948, Kalabis, a committed non-party member, felt the effect both professionally and personally. His thesis on Bartók and Stravinsky (composers then banned as “decadent bourgeois formalists”) was rejected, and his own music aroused suspicion among influential figures within the party. He further aggravated his situation when in 1952, the year of the anti-Semitic show trials, he married harpsichordist Zuzana Růžičková, a Holocaust survivor and daughter of a formerly capitalist family. He found work with Czechoslovak Radio in 1953 and remained there for almost 20 years. Only after the “Velvet Revolution” in 1989 was he finally awarded his doctorate and offered several prestigious posts. He declined them due to failing eyesight and devoted his remaining years to the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation and Institute. Kalabis died in Prague on September 28, 2006.

The marriage between Viktor Kalabis and Zuzana Růžičková was one of exceptional devotion, described by Kalabis as the “centrum securitatis” of his life; it was to Růžičková that he dedicated his Harpsichord Concerto. Commissioned by conductor Räto Tschupp and Camerata Zürich, the Concerto was composed between October 1974 and August 1975. The premiere took place at the Tonhalle in Zürich on March 21, 1977. Růžičková, a tireless advocate for her husband’s music, performed the Concerto frequently at home and abroad (Berlin, Dresden, Budapest, St. Petersburg, Washington D. C., Tokyo, among other cities) and recorded it for Supraphon in 1980. This CD represents the work’s first commercially released recording since that time.

The concerto is an evocative, multilayered composition decidedly at odds with Růžičková’s original request for “something cheerful.” While one hesitates to assign a particular narrative, as each listener will find meaning unique to their own experience, it nevertheless seems possible to hear within the work a confrontation between opposing forces: the individual striving for means of personal expression against the forces of oppression and conformity. The orchestra provides only a fleeting introduction before the harpsichord takes center stage in the opening Allegro leggiero. Brisk, motoric rhythms propel the music forward, the mood deceptively light, with the orchestra at times taking on a sinister martial quality intimated by a footstep-like pulse from the lower strings. A dramatically rhetorical harpsichord solo, by turns confident and resigning, brings the movement to a climax. As the orchestra re-emerges, somewhat reticently, the solo part presses forward unabated until finally, seemingly exhausted, fading to a whisper. A temporary respite can be felt in the extended introduction to the central Andante, but it is an uneasy calm, punctuated by anguished cries. The harpsichord enters with somber, chorale-like chords, considerably at odds with the preceding material, a demarcation in the increasing dichotomy between soloist and orchestra. A drama ensues, with solo strings emerging from the orchestra as if emissaries, tentatively engaging the harpsichord in dialogue. Driving, motoric rhythms return in the Allegro vivo finale. The pace is frenetic, the soloist taking flight as the orchestra pursues its quarry. An interlude of almost tender character offers momentary security and calm, but the sense of unease prevails. The mysterious “footsteps” return, this time even more pronounced, and while a pensive, questioning dialogue between harpsichord and solo violin attempts to find conciliatory ground in the concluding measures, quietly foreboding intonations from the orchestra imply that there are no easy answers. The struggle remains unresolved.

Michael Nyman has been involved with the harpsichord as a solo performer (he studied at the Royal Academy of Music, London, with Geraint Jones, between 1961 and 1964), continuo player, and composer. He first wrote for the instrument in his soundtrack for the 1983 Peter Greenaway film The Draughtsman’s Contract. In addition to the Concerto recorded here, Nyman has written other major works for Elisabeth Chonacka and also Virginia Black. I discovered Michael Nyman’s electrifying and outrageous Concerto for Amplified Harpsichord and Strings (1995) just a few years after its premiere, thanks to the French Conductor Marc Minkowski. Under Minkowski’s direction, I was fortunate enough to perform this work several times, first with the Flanders Opera Orchestra, and then with Les Musiciens du Louvre/Orchestre de chambre de Grenoble. I soon thereafter played the work with the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra (Christian Mandeal), and the Charlemagne Orchestra (Bartholomeus-Henri Van de Velde). Within a basically minimalist sound world, Nyman pushes the technical limits of the harpsichordist to the maximum. The result is thrilling both for performer and audience!

Michael Nyman says of the work:

This Concerto was composed during the winter of 1994/95 for (Franco-Polish harpsichordist) Elisabeth Chojnacka, who gave the first performance with the Michael Nyman String Orchestra on 29th April 1995 in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London. Its history is eccentric and cumulative. I had met Elisabeth in Paris about a year earlier while I was working on the soundtrack for Diane Kurys’ film À la Folie (aka Six Days, Six Nights). I was attempting to persuade her to play my solo piece The Convertibility of Lute Strings (1992) but she expressed a passion only for tangos. As luck would have it, one of the cues of the Kurys score was what I fondly called a tango. Elisabeth showed interest in this and I subsequently turned it in to a harpsichord solo. Sadly, during the writing of the piece my friend the composer Tim Souster died tragically. Elisabeth’s enthusiasm for Tango for Tim encouraged me to write the Concerto for her.

The Concerto is shaped as a very simple ABA form — the outer sections, derived from The Convertibility for Lute Strings, enfold an elaborated version of Tango for Tim. After the first performance, Elisabeth decreed that the true potential of the Concerto could only be fulfilled by the addition of a cadenza. This was duly composed in the summer of 1995 — a toccata derived from harmonies first heard in the immediate post-Tango for Tim, Convertibility material. (Elisabeth subsequently ordained that the cadenza could also have a life outside the Concerto as a concert piece if it had a few extensions added. Hence — inevitably, the title of the piece — Elisabeth Gets Her Way.

Special thanks are offered to Jim Ginsburg, for his vision and belief in this project; Philippe LeRoy for his inestimable work preparing performance material for the works by Rorem and Kalabis; Robert Tifft for his kind advice and support. I also thank Emily Vogt of the Viktor Kalabis and Zuzana Růžičková Foundation for supporting this project.

Jory Vinikour

Album Details

PRODUCER James Ginsburg

ENGINEER Bill Maylone

HARPSICHORDS Tony Chinnery (Vicchio, Italy) after Taskin, 2012. Paul Irvin, Franco-Flemish design, 2011 (Nyman).

TUNERS Mark Shuldiner, Bryan Gore (Rorem)

COVER PHOTO Lisa-Marie Mazzucco

GRAPHIC DESIGN Bark Design

RECORDED November 3, 2016, Wentz Hall, Naperville, IL (Nyman)

March 5, 2018, Feinberg Theater, Spertus Institute, Chicago, IL (Leigh and Kalabis)

May 8, 2018, Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts at the University of Chicago (Rorem)

PUBLISHERS

Walter Leigh: Concertino for Harpsichord and Strings © 1934 Oxford University Press

Ned Rorem: Concertino da Camera © 1946 Boosey & Hawkes

Viktor Kalabis: Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings, Op. 42 © 1977 Bärenreiter Prague

Michael Nyman: Concerto for Amplified Harpsichord and Strings © 1994 Chester Music

©2019 Cedille Records

CDR 90000 188