| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

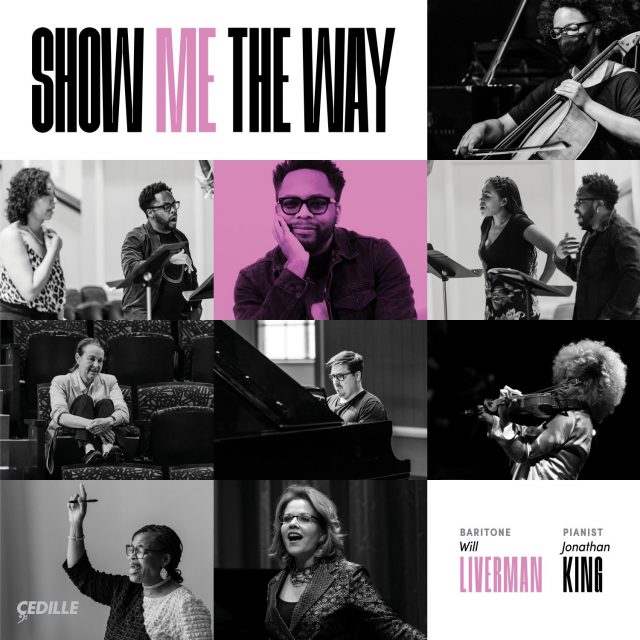

2025 Grammy Award Nominee — Best Classical Solo Vocal Album

Grammy Award-winning, “velvet voiced” (NPR) baritone Will Liverman and pianist Jonathan King present a recital program honoring women in classical music, past and present, on Show Me The Way, Liverman’s second “passion project” recording for Cedille.

Praised as “nothing short of extraordinary” (Opera News), Liverman and King have curated a moving and poignant recital celebrating American female composers from 20th-century trailblazers Florence Price, Margaret Bonds, and Amy Cheney Beach to present-day composers commissioned for this program.

This new album, Liverman’s second with longtime recital partner pianist Jonathan King, is inspired by and honors the singer’s mother, gospel singer Terry Liverman, and their mutual love of song. The Livermans perform together on recording for the first time in their own arrangement of Alma Bazel Androzzo’s cherished hymn If I Can Help Somebody.

Two new song cycles serve as pillars of the recording: Jasmine Barnes’ A Sable Jubilee with a newly commissioned libretto by Tesia Kwarteng that celebrates Black Joy and Libby Larsen’s three movement Machine Head: Ted Burke Poems depicting everyday American life. Liverman premiered the cycles in an “extraordinary recital… as meaningful in content as it was rich with his resonant voice—both elements impressive for their range” (Aspen Times).

Liverman, “one of the most versatile singing artists performing today,” (Bachtrack) is joined by all-star special guests including J’Nai Bridges in a somber new work by Rene Orth and Renée Fleming in Sarah Kirkland Snider’s mysterious and affecting Everything That Ever Was. He sings a duet from Amy Beach’s rarely performed opera, Cabildo, with Nicole Cabell, featuring violinist Lady Jess and cellist Tahirah Whittington.

Also featured on the album are Jonathan King’s arrangement of Ella Fitzgerald and Chick Webb’s You Show Me The Way originally performed by the duo at New York’s Savoy Ballroom, as well as a new work, Spell to Turn the World Around, by Kamala Sankaram, with a text that calls awareness to the destruction caused by wildfires.

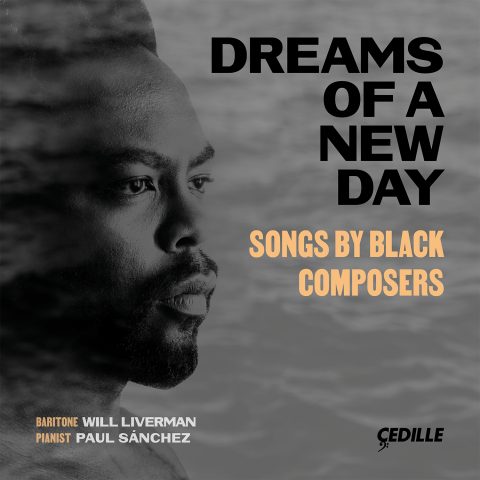

This recording follows Liverman’s “devastatingly beautiful” (The Washington Post), Billboard chart-topping and Grammy-nominated Cedille album, Dreams of a New Day: Songs by Black Composers.

Show Me The Way is produced and engineered by the Grammy-winning team of James Ginsburg and Bill Maylone, with additional engineering by Dan Nichols. It was recorded July 17–19, 2023 in the Sasha and Eugene Jarvis Opera Hall at DePaul University in Chicago, and August 15, 2023 in Lisner Auditorium at George Washington University in Washington DC (for the session featuring Renée Fleming).

Click here to listen to a playlist inspired by this recording.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Will Liverman on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

ELLA FITZGERALD, CHICK WEBB, TEDDY MCRAE, AND BUD GREEN (arr. Jonathan King)

JASMINE BARNES

A Sable Jubilee

FLORENCE PRICE

RENE ORTH

MARGARET BONDS

Four Songs

Artists

1: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

2: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

3: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

4: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

5: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

6: Will Liverman, Jonathan King, J’Nai Bridges

7: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

8: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

9: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

10: Will Liverman, Jonathan King

Program Notes

Download Album BookletPersonal Statement

Notes by Will Liverman

Show Me The Way is a celebration of American song. The program was built in a spirit of collaboration and highlights women in classical music and the power of voices coming together. Every artist on this album is one who has deeply inspired me and whose legacy I aspire to be a part of. From my mom, who nurtured my love of music from day one and sings her own arrangement on the album’s final track, to one of my idols and mentors, Renée Fleming, whose character and devotion to the next generation of musicians and composers has been an enormous source of inspiration to me. My mom is someone who, if she has something to say, will find a way to say it. In the 80’s and 90’s she wrote, sang, and produced her own music. She used to record her songs on cassette tapes, and some of my earliest musical memories were listening to those tapes of my mom singing. That experience probably sparked my love of recording, as well as the idea for this project.

When I’m building a program, it’s important for me to bring in multiple perspectives, because the more voices that are involved, the more opportunities a listener has to connect. In combining solo vocal works with duets and ensemble pieces, I’m also paying homage to colleagues who have inspired my work. Each of their artistries has had a deep impact on me and helped shape who I am as a performer, composer, and curator. I believe all of the musicians on this program feel that, as the world changes, so does music, and that we can’t be rooted in what we’ve always done. The program features 20th-century classical composers who were pioneers in the field, such as Amy Beach and Florence Price, as well as present-day composers like Sarah Kirkland Snider and Kamala Sankaram, who are current industry movers and shakers. So, in addition to preserving important pieces of the past for future generations through this recording, we’re also hoping to continue supporting contemporary legacies through commissions and recording new works. People may resonate differently with each song, but the common thread is that we’re searching for one another in a world that can oftentimes feel vast and expansive, and that, at the end of the day, we’re all connected. We all have the power to help each other, to lift each other up. I hope that message shines through as you listen to Show Me The Way.

Program Notes

Notes by Jonathan King

“You Showed Me The Way” by Ella Fitzgerald, Chick Webb,

by Ella Fitzgerald, Chick Webb, Teddy McRae, and Bud Green

Arranged by Jonathan King

Sandwiched between two world wars and ushered in by the infamous Wall Street crash of 1929, 1930s America was a decade defined by hardship, crisis, and poverty. In popular music, swing was king and the Savoy Ballroom, nestled in the heart of New York City’s Harlem neighborhood, saw some of the country’s greatest big bands, jazz singers, and Lindy Hoppers. One of the only dance clubs in town to have a non-discrimination policy, the Savoy also championed black artists throughout its history and hosted the likes of Chick Webb, Count Basie, and Dizzy Gillespie, among countless others. On the heels of her Apollo Theater discovery, Chick Webb hired the 18-year-old Ella Fitzgerald in 1935 to sing regularly with his house band at the Savoy, launching her career towards international stardom and giving the world some of the era’s greatest original tunes and arrangements. Such was the genesis of You Showed Me the Way, an original tune cowritten in 1937 by Fitzgerald and the Chick Webb Orchestra. With lyrics that speak of overcoming distress, through the help and love of others, the slow swing lilt of this original chart offered hope and lightness in a time otherwise known for its despair. In this arrangement, dissonant chords and slow, plodding quarter notes not only paint the distress and searching tone of the song’s text — they also create a sense of longing for those we love to show us the way in a time marked by pain, hardship, and uncertainty.

“A Sable Jubilee”

Text: Tesia Kwarteng

Music: Jasmine Barnes

One of the first inspirations behind Show Me The Way was the commissioning of a new text and composition to celebrate Black Joy. As her first commissioned libretto, Tesia Kwarteng offered a poetic triptych of pride and celebration titled A Sable Jubilee, a text that Jasmine Barnes matched with musical brilliance and originality. The paired result is an encyclopedia of unashamed delight and elation.

1. INSPIRATION

Kwarteng’s first poem, Inspiration, begins with the words “Black joy is a tapestry,” and perhaps there is no better word to define it. The poem relays a survey of experiences, including “electric sliding,” “sweet potato pie,” “a soul train line,” “hair that coils,” and “cocoa butter scented hugs.” Kwarteng’s words leap in rapid succession as if the poet cannot contain her joy. Barnes matches this elation from the first measure of the song with a rhythmic string of repeated eighth and 16th notes broken only by leaps at the fifth and octave, as though someone is nearly bursting with excitement and anticipation before the first word is even sung. Barnes’ use of 16th-note passages in the piano is a distinguishing factor throughout this movement, sometimes with infectious syncopation, sometimes in repeated note succession, sometimes in falling sequences, and always closely connected thematically to the text it is accompanying. Barnes does not shy away from quoting famous musical material that directly relates to the text, including melodic material from the hymn, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” Frankie Beverly and Maze’s “Before I Let You Go,” and Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together.” At other times, Barnes imitates specific styles of music, including Afro-jazz, R&B, soul, and funk. Throughout, the piano is a tour de force of rapid movement, orchestral in its textures and layers. The contrasting smooth vocal line seems almost to be secondary to the piano in portraying emotion, floating above the flurry of accompaniment in a through-composed style, while the piano maintains structures of primary, secondary, and developed themes in a quasi-sonata style. The singer merely follows the journey, clearly exclaiming each defining moment of Black Joy.

2. LUXURY

Written to be performed without pause between movements, the second song shifts abruptly from the previous key of D-flat major to C major, and in a highly contrasted new soundscape that Barnes labels “surreal.” Simple scalar patterns noodle for several measures until the singer intones, “We’re proud of ourselves. Why wouldn’t we be?” Just as the first poem expresses joy in Black culture, Kwarteng’s second text expresses joy in being Black, in and of itself. “Trendsetters, history makers, creative, always imitated,” Kwarteng defines Black individuals with poignant truths, adding that “this joy is radical/Powerful and must be protected.” Throughout, Barnes sets this text with the singer at the forefront and the piano serving as accompaniment. As the song progresses, the piece’s rhythmic energy intensifies. At the singer’s exclamation, “A way of being, living, moving, breathing…” the piano begins to move into 16th note patterns that roll continuously through various key centers until the penultimate measure of the movement, when the song comes to a quick, yet calm, pause.

3. ELEVATION

The third movement begins with a seamless transition to A minor. The composer indicates that the piano should “shimmer” while the singer states, “A sparkling legacy/ Unapologetically shining like Opal.” Here, Kwarteng’s words move beyond joyful exclamations and toward defining Black experience as a transcendent truth. “Our darkness is no illusion/ It was designed to illuminate endless originality…” Barnes achieves a very special soundscape (with open sonorities in the left hand and 32nd-note motives in the right) that is simultaneously dark and illuminating, just as the text suggests. The 32nd-note patterns eventually overwhelm the piano writing and move the tonal center to its parallel, A major. There is a sudden bell tone that ushers the movement into a call and response moment between voice and piano before an ecstatic praise session of syncopation and gospel riffs takes off. As Kwarteng’s words begin to take on an almost esoteric nature, Barnes’ music shifts to an obscure tonal edge over a C pedal tone, all the while still maintaining its syncopated energy. This gives way to a return of the shimmer at the movement’s beginning, as the voice quietly recedes into the piano texture on the words “creating our own.” The piano has the final word, as it arpeggiates down on a C-seven harmony before cadencing with a mediant relationship to A major; a moment that feels a unique creation and, at the same time, imparts a clear sense of finality.

“I Grew A Rose”

Text: Paul Laurence Dunbar

Music: Florence B. Price

Although a child prodigy of rare distinction, Florence Price lived a life tainted by discrimination, marital abuse, and financial hardship. Indeed, after graduating as valedictorian from Capitol High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, at the age of 14, Price concealed her African American roots by disguising herself as Mexican in order to attend the New England Conservatory without fear of discrimination. After returning home to Little Rock, Florence married lawyer Thomas J. Price. Following the loss of their first born at infancy, the couple raised their two daughters in the community. After several racially charged incidents, including Florence’s denied membership, on the basis of her race, to the Arkansas Music Teachers Association and the horrific lynching of John Carter just blocks from their family home, Florence and her husband fled the state of Arkansas and relocated to Chicago in 1927. There, their marriage deteriorated quickly and Florence filed for divorce in 1931 after suffering significant physical abuse and threats on her life. That any art at all, let alone the beauty of Price’s rich and melodic musical language, could come from such years of hardship is a testament to her brilliance and artistry.

Combining the text of Dunbar’s companion poems Promise and Fulfillment, Price’s I Grew a Rose is a song that, with its repetitive nature and memorable melodic content, resembles tunes from “golden age” Broadway musicals. Price’s work is more complex, however, as she intertwines the melody between the piano and voice, the two sharing more of a duet than a solo with simple accompaniment. Price also weaves in and out of keys seamlessly, painting “sun and dew” in the brighter timbre of D major, as opposed to the song’s distant central key of A-flat in this lower-key setting. The piece sits in a high tessitura for the singer and requires an acrobatic voice able to manage octave leaps and arpeggiated motives. Accelerando markings aid texts of exuberance (“At last, oh joy!”) and moments of silence help to bridge lines of text and character shifts. Dunbar’s words about stolen beauty perhaps frame for Price relationships that were stolen away from her in violence and prejudice.

“A Prayer”

Text: Sara Teasdale

Music: Rene Orth

Sara Teasdale’s A Prayer is a poem simple in structure yet rich in meaning, and Orth sets it in a similar vein. Scored for mezzo-soprano, baritone, and piano, the duet begins with a slow, repeating two-voice figure in the piano, outlining a C minor tonal center. The mezzo-soprano imitates the figure on a hum, creating a space altogether hypnotic and, as directed by the composer, “somber.” The baritone introduces the first line of text, but it is the mezzo who completes his sentence, creating a sense of togetherness that is a distinguishing feature of this piece. Orth explores high registers in both voices to create a “storm of mirth,” before a new, even more hypnotic texture begins to take shape. Maintaining evenness and solemnity here is difficult for the pianist, as the right hand must keep a steady quarter to eighth note pulse against a left hand that plays triplets at the half note. A low bass line also emerges from this texture, creating a polyrhythmic complexity that should sound anything but. The singers continue to weave in and out of one another’s sentences until they arrive together at the declamation, “let me love…”. The piano part becomes turbulent as it highlights the throws of love and, per the poem, the strength needed to endure it. The rhythmic intensity recedes measure by measure, as if in waves, and the duet ends as simply as it started, this time with a D minor tonal center. Love has returned us to where we began, but now elevated to a higher plain of existence.

FOUR SONGS

Text: Edna St. Vincent Millay

Music: Margaret Bonds

Margaret Bonds wrote six musical settings to poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay. She compiled four of these into a cycle titled, simply, Four Songs. Although they never met, both women were deeply connected in their commitment to gender and racial justice as reflected in their artistic outputs. Indeed, Bonds carefully selected four poems from Millay’s published collections to create a particular story: a narrative that journeys through one protagonist’s loss of love, reclaiming of self, and acceptance of a new reality. This is the set’s first recording in a medium voice key (using a recent edition by Hildegard Publishing Company).

1. EVEN IN THE MOMENT

Bonds masterfully sets a text (from Millay’s sonnet collection, Fatal Interview) mourning a love lost. Writing in an impressionistic style, Bonds employs a repeated quintuplet arpeggiation on a C major seven chord (triad plus the note seven steps above the chord’s root) in the upper register of the piano throughout her song. This might denote a kiss of warmth and romance were it not consistently accompanied by a tritone figure fixed in an eerie E minor. This kiss is void of any pleasant feeling, and is instead an icy reminder of the frost that has killed all things once thriving. Bond’s music exists in dissonant gestures, only once cadencing to a calming B major as the narrator hopes for pleasant seasons amidst the reality of winter.

2. FEAST

Bonds matches the rawness of Millay’s poem (from her Pulitzer-winning collection, The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems) with a driving, dissonant edge. For this ironic “Feast,” Bonds creates an unhinged quasi-scherzo, hardly finding roots in tonality, with mixed meters, an atonal melodic contour, and extreme tessitura suggesting a narrator truly intoxicated by their reality of “want” and “thirst.” As the narrator resigns to exist in such a state, so the short movement suddenly resolves on a calm cadence in A-flat major.

3. I KNOW MY MIND

The longest of the four songs, I Know My Mind stands as a resolute pillar that upholds Bonds’ cycle as a whole. The poem (again from Millay’s Fatal Interview) provides a character shift from despair and lament to one of decisiveness and determination in love lost. Bonds writes “baldamente con agitamento” to characterize the movement. This “boldness” is instantly realized in an unobscured minor-key tonal center and unrelenting double-dotted rhythms. Dense yet open sonorities further characterize a sense of nobility. The interpretation moves forward as a royal procession, the narrator exclaiming, “I know my mind and I have made my choice . . . you have no voice in this, that is my portion to the end.” The narrator does not deny continued interest in romance amidst self-actualization, stating, “Mistake me not / unto my inmost core I do desire your kiss upon my mouth,” referencing the desert of want described in the previous movement. Still adorned in decision, the “a tempo pomposo” continues

until the final open-fifth intervals in the piano, sealing one of the most arresting characterizations in song literature.

4. WHAT LIPS MY LIPS HAVE KISSED

The A minor pillar of the previous movement is softened to its parallel A major in this tender setting of Millay’s What Lips My Lips Have Kissed (from The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems). Again referencing the kiss that opened the cycle, Bonds creates a moving conclusion to her story as the narrator gently sings, “What lips my lips have kissed . . . I have forgotten.” With a lush and romantic musical sensibility, Bonds seems to reserve her most beautiful expression for the moment her narrator finally moves away from the love of others and accepts the love found only within herself. There is still a sense of melancholy in the lilting countermelody of the piano during the song’s interlude, however, as the narrator reflects on the “quiet pain” that lingers from lovers past. In a final and quiet declamation, Bonds has the piano double the voice as it sings “I only know that summer sang in me / A little while, that in me sings no more.” The optional high-note ending is a must for any singer who acknowledges the beauty found in moving on and the pain felt in letting go

“Ah, Love is a Jasmine Vine”

FROM CABILDO, OP. 149

Libretto: Nan Bagby Stephens

Music: Amy Cheney Beach

Amy Cheney Beach wrote only one opera in her lifetime, a curious one-act chamber piece scored for singers and piano trio. Penned in the summer of 1932 while on retreat at the MacDowell Colony, Cabildo tells the true story of smuggler Pierre Lafitte, falsely imprisoned and condemned within the New Orleans Cabildo (a traditional Spanish town hall still in existence today) during the Battle of New Orleans at the tail end of the War of 1812. In truth, General Andrew Jackson made a private agreement with Pierre and his brother Jean to assist the American army in defeating the British in return for Pierre’s release. In typical operatic fashion, Stephens’ libretto abandons fact and makes it the ghost of Lafitte’s recently deceased lover (a fictional character), Lady Valerie, who frees him from his cell. The love duet that ensues is the excerpt we offer on this album.

Although a large portion of the opera employs distinctive Creole folk melodies and idioms, this particular duet is based on a Beach art song written decades earlier, When Soul is Joined to Soul, Op. 62, and is strikingly different in character from the rest of the opera. At this climactic moment, Beach uses long sweeping melodies in the vocal lines with several indications for rubato throughout, often doubling soprano and baritone with violin and cello, respectively. The consistently pulsating subdivisions in the piano are typical to many of Beach’s songs, creating a layer of impetuousness and passion. Common to the romantic era, Beach writes this duet in the complex key of G-flat major, a far departure from the G Major prologue at the beginning of the opera, perhaps to highlight the profundity of this otherworldly and clandestine meeting.

“Spell to Turn the World Around”

Text: Kathryn Smith

Music: Kamala Sankaram

Wildfire devastation is not a new topic in world affairs. It has only been in recent years, however, that artistic media have been frequently engaged to bring awareness to the urgent environmental reality we now face. Kathryn Smith’s poem, Spell to Turn the World Around, is no exception and does not shy from the brutal realities of fire and the absolute destruction it brings. Words of brutality — “birds battered,” “feathers damp with blood,” “the firefighter’s grave” — all paint true stories of what people have had to endure battling terrifying flames. Kamala Sankaram’s setting is a poignantly honest musical representation of these harrowing words. She writes, “As a New Yorker, while I had an awareness of the devastation of the wildfires along the West Coast, Kathryn’s words really connected me to the full weight of it, of the lives (both human and non-human) hanging in the balance. Little did I know that I would write this piece accompanied by the orange skies of our own summer of wildfire in New York City, soon to be followed by a snowless winter and the hottest year on record.” Her soundscape is bleak and eerie. String plucks from inside the piano echo atonal motives Sankaram constructs by assigning numbers to the letters of the words “smoke,” “wildfire,” and “breath,” and matching those numbers to the 12 notes of the equal-tempered scale. The result is something euphonious and systematic, a feeling that leaves the listener both emotionally invested and aware of an inevitable churning that we cannot ignore.

“Songs to the Dark Virgin”

Text: Langston Hughes

Music: Florence B. Price

We know that Price set the sensual text of Langston Hughes’ Songs to the Dark Virgin to music in 1935, less than five years after her divorce. She was introduced to Hughes through their mutual friend, Margaret Bonds, who housed Price and her children after her divorce. As part of her cycle, Four Songs from The Weary Blues, Price set “Songs to the Dark Virgin” with a lush and dense romanticism, particularly evident in this lower-key setting of A-flat major. Price introduces a simple melody to set the first stanza of text and then modifies it slightly in the other two stanzas, almost as a miniature theme and variations. The first line of each stanza, “Would that I,” may suggest the pain of Price’s recently broken marriage. Perhaps there is a longing or an unrealized desire in her musical intention. Other words — “absorb,” “wrap,” “hold and hide” — beg a lingering and an indulgence: a fantasy the narrator should hate to depart to return to the bitter realities of a broken life.

“Machine Head: Ted Burke Poems”

Text: Ted Burke

Music: Libby Larsen

Ted Burke, an American poet, critic, and bookseller, runs an infamous used bookstore, D.G. Wills Books, in La Jolla, CA. The shop is known for its cozy interior, scholarly collections, and high-profile visitors, including the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Christopher Hitchens, Billy Collins, Gary Snyder, Irish Chang, Oliver Stone, Sean Penn, and Jim Belushi, to name a few. In many ways, to know Ted Burke is to know his bookstore and its many guests, in that his writing style is one that infuses the intelligence, artistry, and wit of each person who walks through his door. Given the particular nuance towards rhythm and jazz in his poetry (Burke is also a highly accomplished harmonica player), it is no wonder that composer Libby Larsen leaned into his works when commissioned to write a song cycle for this album. When she first conceived the work, she wrote, “For this piece I want to be inspired by our own language, our own rhythms and the way we (our culture) use ordinary, every-person objects (like a cigarette, a radio, a cardboard box you find in your garage…) to transport us into our interior selves where we articulate emotions that are universal.” The result is indeed transporting, each song revealing a unique corner of Burke’s writing and the world he inhabits.

REXALL

Larsen’s first song opens with an infectious, smokey blues riff that grooves throughout most of the movement. Just five measures in, we also begin to hear a faint but distinct quote of the Tennessee Waltz, a popular tune by Redd Stewart and Pee Wee King that reached the height of its fame in 1950 with a recording by Patti Page. Tie into this mix the name of the poem, Rexall, a popular, mid-20th century American drugstore chain, and it is unmistakable, even before the singer introduces any text, that we are in the 1950s American deep south. The poem frames a moment in time where a father and son are waiting, one more patiently than the other, for a mother to return to the car from her shopping. The son wants a comic book and is on the verge of a meltdown, humorously portrayed by abrupt, dissonant major seconds in the piano’s treble register. Larsen’s unending blues riff in the left hand serves as a demarcation of time, like the second hand of a clock ticking, amidst the “crying jag” and “sniffles” of the son’s tantrum. Time is suspended only when the father lights his Old Gold cigarette (another mid-century nod) and turns up the car radio to listen to Patti Page sing her famous tune. Here, Larsen’s bass groove halts and we enter a surreal sound-world in G major with another unmistakable quote of the Tennessee Waltz, perhaps a musical representation of the father’s internal escape from his crying son and the waiting game he is playing with his wife. He imagines her browsing up and down the aisles, which brings him out of his fantasy waltz and back into the gnawing blues groove. “Not everything is funny or for fun,” he tells his son. “Sometimes you just have to wait.” The singer sings a blues note on the word “wait,” obscuring the key from a minor mode to a major one, while the bass groove gets the final word, slowing to a quiet end.

MY FATHER INTERCEPTS MY TRIP TO ANOTHER PLANET

In every way that Larsen’s previous song setting portrays the passing of time, her second song does the opposite. Here, Burke writes an autobiographical vignette of his childhood as he plays with an old cardboard refrigerator box in his garage. Larsen’s opening, marked “unbound from gravity or progression,” is mesmerizing as the pitches seem pulled out of thin air in a slow, floating fashion. Eventually, we are pulled into a D pedal tone, contrasted by a repeating diminished-seventh interval in the right hand, providing an impressionistic ground for the singer to tread on. Burke’s text is full of boyhood wonder, describing the holes he has cut with his pocketknife and the ankles and outfits he can observe from his fort. Soon, the fort becomes an “ever evolving ship,” and Larsen’s “unbound” sound palate with fast moving 16ths at the fourth. Sextuplet repeated note figures in the right hand paint a peculiar picture of the ship’s controls before a written-out doppler effect in the piano depicts the race car that the spaceship has suddenly morphed into. Whole tone patterns are heard throughout the movement, most notably when the race car suddenly changes into an airplane. Next it is a “fast train,” then a “jet,” or “rocket to the stars,” each shift met with clever musical inventions to depict the next traveling machine. The 16ths begin to mellow as Burke writes, “back in time for Flintstones…” and soon we return to our unbound existence, as the boy opens his eyes to discover his father carrying him off to bed. Larsen quotes the Cole Porter song, I Love Paris as Burke describes his father singing the song’s words as he drifts off to sleep. The piano cadences on what feels very much like a dominant chord as Larsen re-employs her D pedal tones, while the Cole Porter melody seems to find its tonal center in G major.

MACHINE HEAD

Larsen begins her set of songs with a blues and ends with a “hard driving boogie” — the perfect musical companion to a barrage of fast-moving text: Burke’s Machine Head seems to find its root in beat poetry as it describes, or perhaps laments, an ever-changing world of machines. Larsen employs a chromatic 16th-note motive that rarely stops; instead, it evolves with the text by way of changing articulation, octave displacements, modulations, and other creative devices. As with a well-crafted jazz improvisation, there are moments where the text seems suddenly to adjust rhythm and even stop, just momentarily. Larsen meets these moments with a musical halt, most notably over an F-sharp-seven sonority at the grand declamation of “machines of gratuitous good looks.” These pauses are never long, however, and the incessant 16ths grow increasingly emphatic, while always remaining mechanical in nature. Spastic rhythms in the right hand begin to surface, as though the poem’s machines are beginning to short circuit. But it is the singer who is eventually overcome, exclaiming, “My machines know all my sounds, the rhythm of bad habits they are powerless to match.” Larsen saves the highest sung note — a sustained high A-flat — for the last word of the entire cycle. The machines barrel onward and only stop when the poet runs out of text. The marriage of this boogie rhythm to Burke’s descriptive and rhythmic words creates a perfect ending to this inventive and eclectic set of songs.

“Everything That Ever Was”

Text: Tracy K. Smith

Music: Sarah Kirkland Snider

Snider writes, ”By turns mysterious, reflective, elegiac” as the character description to begin her duet, Everything That Ever Was. And this spacious work is, indeed, defined by its mysterious nature and ever-slowly turning movement. Eschewing a key signature, Snider defines her sound palate more by sonority than harmonic language, often applying sequences of intervals at the third and sixth, sometimes in diatonic scalar patterns, at other times in whole tone movement. Still, the piece is rooted firmly in tonality, and may be interpreted as a ternary form, with the B section exhibiting a much more rapid form of turning than the outer sections as it sets descriptive texts such as, “your eyes danced toward mine” and “hands . . . working a thread in my lap.“ The vocal lines weave around one another throughout, at times completing each other’s sentences or telescoping text in layers as though one is echoing the other. Tracy K. Smith’s words evoke space and a shift in the understanding of time from an ever-passing inevitability to an eternal collection of moments that affect each of our presents and futures. Smith’s lyrics combined with Snider’s soundscape produce a work that’s poignant, intimate, eternal, and deeply beautiful.

“If I Can Help Somebody”

By Alma Bazel Androzzo

Arranged by Terry and Will Liverman

A song of eternal importance and universal truth, If I Can Help Somebody has been cherished, performed, and recorded by artists worldwide since its commission for the National Tuberculosis Society in the mid-20th century. Indeed, Alma Bazel Androzzo’s hymn has been immortalized by the voices of Turner Layton, Billy Eckstein, Doris Day, Joseph Locke, and even at the hands of Liberace. Martin Luther King, Jr. ended his famous speech, “The Drum Major Instinct,” with lines from the hymn’s text. This is said to have been the inspiration for the famous gospel setting Mahalia Jackson recorded in 1964. It is this specific interpretation that inspired mother and son duo Terry and Will Liverman’s new, heartfelt arrangement. Speaking of his mother, Will shares that “she has always paved her own way with her music and singing, and I wanted to honor her in some way on this project.” With Terry’s rich, dramatic vocal timbre and Will’s stylized playing at the keyboard, this song ends our program on a mission to pursue the good of humanity, and the prize of a life well-lived in service toward one another.

Album Details

PRODUCER

James Ginsburg

ENGINEERS

Bill Maylone

Dan Nichols (Sankaram, Snider)

COVER PHOTOS AND LAYOUT

Jaclyn Simpson

COVER PHOTO (LADY JESS)

Naliya Sabis

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Bark Design

RECORDED

July 17–19, 2023 in the Sasha and Eugene Jarvis Opera Hall at DePaul University, Chicago, IL

August 15, 2023 in Lisner Auditorium at George Washington University, Washington DC (Sankaram, Snider)

PUBLISHERS

Fitzgerald, Webb, McCrae, and Green:

You Showed Me the Way © 1937 Robbins

Music Corporation

Barnes: A Sable Jubilee © 2022 Jasmine

Barnes Music

Price: I Grew a Rose © 1977 Estate of

Florence Price

Orth: A Prayer © 2023 ReEnthrone

Productions

Bonds: Four Songs © 2020 Hildegard

Publishing Company

Sankaram: Spell to Turn the World

Around © 2022 Kamala Sankaram Music

Price: Songs to the Dark Virgin © 1941

G. Schirmer, Inc.

Larsen: Machine Head: Ted Burke

Poems © 2022 Libby Larsen Publishing

Snider: Everything That Ever Was © 2023

G. Schirmer, Inc.

Androzzo: If I Can Help Somebody © 1947

Boosey & Hawkes

CDR 90000 226