| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

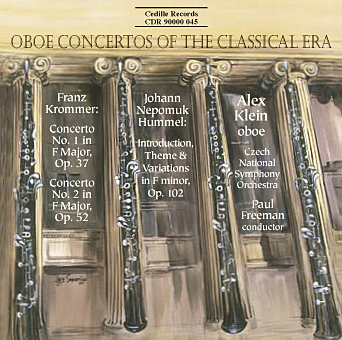

Oboe Concertos of the Classical Era

Alex Klein, Paul Freeman, Czech National Symphony Orchestra

This CD of oboe concertos breathes fresh life into music of two classical-era composers whose reputations once rivaled those of their contemporaries, Mozart and Beethoven.

Alex Klein, principle oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, performs works for oboe and orchestra by Bohemian Franz Krommer (1759-1831) and Bratislava-born Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837). “Their music proves that the story of the classical era doesn’t end with the ‘Big Four’ — Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert,” Cedille producer Jim Ginsburg says.

Krommer achieved a position in Vienna that eluded both Mozart and Beethoven: imperial court composer to the Hapsburg dynasty. He wrote more than 300 works, and his music was published in Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, and even the US. Modern scholars view his solo concertos for wind instruments as his most distinctively original achievements.

In the late classical era, the presence of a significant number of virtuosic oboe players and new oboe designs opened the way for composers to write interesting, challenging music for the instrument. The solo parts in Krommer’s oboe concertos offer rapid passage-work and wide leaps between high and low notes reminiscent of Mozart opera arias.

A child-prodigy pianist who studied briefly with Mozart, Hummel went on to succeed Haydn as music director for Prince Nikolaus Esterhazy. He maintained a long but stormy friendship with his intimidating rival, Beethoven. Hummel’s Introduction, Theme, and Variations in F minor, Op. 102, exemplifies his position on the cusp of the classical and romantic eras. The darkly dramatic, expressive Adagio introduction leads to brighter, cheerier musical vistas.

Oboist Klein says the performances on this CD seek to replicate the bright, open, high-volume sound that classical composers had in mind. Cedille’s Ginsburg says he and engineer Konrad Strauss set out to achieve a more natural-sounding, equitable balance between orchestra and soloist, compared to recordings “where it sounds like the orchestra is in the next room.”

In Klein, Cedille has enlisted an oboist whose playing produces “pure pleasure . . . [an effortless flow of lovely sound shaped with the most intelligent artistry” (Seattle Times). His honors include taking first prize in the 1988 International Competition for Musical Performers in Geneva, Switzerland — the first oboist to do so since Heinz Hollinger three decades earlier. In 1995, Klein became principal oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ KROMMER (1759–1831)

Oboe Concerto No. 1 in F major, Op. 37

FRANZ KROMMER (1759–1831)

Oboe Concerto No. 2 in F major, Op. 52

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL (1778–1837)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletOboe Concertos of the Classical Era

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

“All roads lead to Rome”; or so it was said in ancient days when the Roman Empire encompassed all the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea, plus a good chunk of Western Europe and the British Isles. Rome fell from its pre-eminent position under pressures both internal and external, but the idea of “empire” persisted in European history for centuries — not dying out entirely until the end of World War I in 1918. From the early Middle Ages onward, many nations were at least nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire, founded by Charlemagne.

By the 18th century, imperial power had become consolidated in the Hapsburgs, the dynasty that ruled Austria-Hungary from the city of Vienna. And although the Vienna of the Hapsburgs was not the political colossus that Rome under the Caesars had been, it became true that virtually all roads led there, especially for musicians. The emperor’s court and chapel, plus the smaller but no less music-loving households of the Viennese nobility, were magnets drawing composers, instrumental virtuosos, and singers from provincial capitals and remote villages to find work, sell their scores, and make a name for themselves in the most musical city on earth.

Of the great Classical-Romantic “Viennese” composers, only one, Franz Schubert, was actually born there. Haydn and Mozart came from smaller Austrian towns, Beethoven from the German city of Bonn, Brahms from Hamburg. There were others: around the turn of the 19th century many successful composer-performers migrated to Vienna from what is now the Czech Republic, then a province of the Empire known as Bohemia. Their names — Leopold Kozeluch, Anton Reicha, Johann Vanhal, Jan Vorisek, the brothers Anton and Paul Wranitzky — are not terribly well remembered today, but they held important posts in their adopted city, made a good living, served their patrons well, and left behind a wealth of music that is worth hearing. One of these Bohemian emigrés was Franz Krommer — Frantisek Kramár in the original spelling.

Krommer was born in 1759 in the town of Kamenice, where his father was both inn keeper and mayor. His uncle, church choirmaster in a nearby town, taught him to play the violin and the organ. He was in his early 20s when he first went to Vienna, but found it hard to gain a foothold in the city’s competitive environment. He spent several years in Hungary, employed by princes and churches as a violinist, composer, and choir director. When he returned to Vienna in 1795, he was a seasoned professional. After some years of theatre work, he entered the emperor’s service in 1815, and three years later won the coveted post of imperial court composer: the job neither Mozart nor Beethoven ever achieved. The successor to his countryman Kozeluch and before him, Antonio Salieri, Krommer was the last to hold the official court-composer position. By the time of his death in 1831, musical economics had changed such that even emperors stopped employing composers as personal staff members.

A biographical essay by Othmar Wessely notes that “Krommer was one of the most successful of the many influential Czech composers in Vienna,” and that he wrote over 300 works. “Krommer’s reputation is attested by the rapid spread of his compositions in reprints and arrangements by German, Danish, French, English, Italian and American publishers,” Wessely says, “and equally by his honorary membership of the Istituto Filarmonico in Venice, the Philharmonic Society in Ljubljana, the Musikverein in Innsbruck, and the conservatories [of] Paris, Milan and Vienna. With the exception of piano works, lieder and operas, Krommer cultivated all the musical genres of his time, and was regarded (with Haydn) as the leading composer of string quartets, and as a serious rival of Beethoven. The present view, however, places his solo concertos for wind instruments as his most individual accomplishments.”

Krommer was fond of wind instruments in other contexts too: he produced several scores for the nine- or ten-member wind ensembles that the Viennese called Harmoniemusik, and combined flutes and clarinets with strings in chamber music. His list of concertos includes several for his own original instrument, the violin, plus pieces for flute, clarinet, and two for solo oboe, written in 1803 and 1805.

The late Classical era boasted quite a number of virtuosic oboe players, some of whose names have survived. Mozart wrote oboe works for his colleagues Giuseppe Ferlendis and Friedrich Ramm; Krommer’s first concerto was dedicated to a fellow Bohemian emigré, Josef Czerwenka, first-chair oboist in the Vienna Court Orchestra. The oboe began to develop its solo potential during this time, as Alex Klein has explained, because technical innovations made it possible to keep the instrument in better tune, and a new type of central bore greatly extended its range of high notes. “For Mozart and for Krommer, this meant greater freedom to write interesting, challenging music for the oboe,” Mr. Klein says.

The solo parts in both Krommer concertos are notably virtuosic, featuring rapid passage-work and wide leaps from high notes to low and back again that are reminiscent of Mozartean opera arias. Stylistically, the first concerto very much recalls Mozart, while the second leans toward Beethoven. They are laid out using the basic pattern those composers favored for their concertos: an opening movement in sonata form, with a long orchestral introduction before the soloist enters; a lyrical Adagio; and a Rondo that brings each work to a dramatic conclusion.

Discussing the nearly-forgotten life and work of an Austro-Bohemian composer named Ignaz Brüll, a friend and valued colleague of Brahms, the German musicologist Hartmut Wecker recently wrote: “From today’s perspective, the musical history of the 19th century appears to reduce itself to a few big names whose works still continue to dominate our concert halls and opera houses. But appearance and reality are far apart: the everyday music of the epoch, and contemporary taste, were in fact shaped by a large number of finely-trained composers, most of whom have left little behind but their name, even though in their own time they ranked as artists of international stature.”

Johann Nepomuk Hummel was a composer, performer, and teacher who definitely achieved international stature, and though music-lovers of today are aware of much more than just his name, he still tends to be dismissed as second-rate. A few minutes actually spent listening to his music dispel this attitude right away. No, he was not another Mozart or Beethoven: very few artists in any generation are endowed with that degree of genius. Even with a lesser spark of genius, though, he left a legacy well worth reinvigorating. To judge from recent recordings, it appears that his works are indeed undergoing a bit of a revival.

A child-prodigy pianist, he briefly studied with Mozart, and like his master, embarked with his violinist-father (shades of Leopold Mozart!) on a youthful recital tour that took him all over Germany, and to Denmark, Scotland, and England. (The family originated in the city of Bratislava, now in the Republic of Slovakia, but like so many other ambitious musicians, his father perceived opportunities in Vienna and moved there in 1786 when the future composer was 8 years old.)

After his prodigy years, the young Hummel returned to Vienna, undertook studies with the city’s leading musical names — including Albrechtsberger, Salieri, and Haydn — and supported himself by giving piano lessons. In 1804, he succeeded Haydn as music director for Prince Nikolaus Esterhazy, at the splendid estate in rural Austria where concerts and opera productions were on a level with those in Vienna. Hummel returned to the capital seven years later; though he continued to make his reputation as a composer, he also resumed his pianistic career and made many concert tours. He became music director for the ducal court in the German city of Weimar in 1818, remaining there — except for tours, and frequent returns to Vienna — until his death in 1837.

The supreme musical figure of Hummel’s time was Ludwig van Beethoven. The two were for the most part friendly rivals, though there were occasional conflicts. Taking the Weimar position, and continuing to appear as a pianist — a role Beethoven was forced to abandon because of his deafness — effectively removed Hummel from the other man’s orbit. Writing about Hummel’s student years in the Vienna of the 1790s, his biographer Joel Sacks notes, “The most momentous event of the period was Beethoven’s emergence… which nearly destroyed Hummel’s self-confidence.” Well it might have, but he seems to have avoided any permanent inferiority complex. “Despite constant partisan warfare among their disciples,” Sacks writes, “the two began a long, but stormy, friendship.”

“As a composer, Hummel stands on the borderline between epochs,” in Sacks’s view. “His reputation now is that of a virtuoso specialist in piano music — something of a 19th-century trait. This view of him, however, is grossly incorrect. When his little-known unpublished works and the bulk of his printed ones are placed beside his better-known compositions, it becomes clear that his work embraced virtually all the genres and performing media common at the turn of the century: operas, Singspiels, symphonic masses and other sacred works, occasional pieces, chamber music, songs, and of course, concertos and solo piano music, as well as many arrangements. Only the symphony is conspicuously absent (and this fact alone testifies to his deeply-felt rivalry with Beethoven).”

The list of Hummel’s works for solo instrument with orchestra encompasses, naturally, many piano concertos, plus works for trumpet, mandolin, bassoon, and the unusual pairing of viola and guitar. His 1820s Variations for oboe and orchestra are arranged from a Nocturne he originally composed for piano duet.

Although the work’s Adagio introduction is in F Minor, the sprightly main theme and its variations are in the major mode. Few better examples could be found of Hummel’s position on the cusp of the Classical and Romantic eras. The Adagio is darkly dramatic and very expressive, but after a suspenseful chord the curtains are drawn open and we are in a brighter world, where a tuneful, eminently cheerful theme is ingeniously elaborated with many changes of harmony, pace, and figuration. Not a profound piece, perhaps, but a miniature gem of musical craftsmanship to charm both players and listeners.

The performances on this CD deliberately seek to replicate the bright, open, high-volume sound that Classical-era composers desired, according to Mr. Klein. It is a mistake, he believes, to produce a delicate tone-color in music from this time. With Baroque music, the sound ideal for the oboe is a mellow, softer tone, but that is because the instrument known to Bach and Handel had a different type of bore, and thus a much different timbre. “The Baroque oboe is analogous to the viola,” Mr. Klein says, “the Classical oboe, to the violin: brighter and higher. All three works on this CD provide excellent examples of Classical oboe writing.”

Mr. Klein also comments on the ornamentation practices appropriate to concertos from the Classical period. “Ornaments, and ornamentation opportunities, come less frequently in Classical compositions than in Baroque ones, but the practice was still favored,” he tells us. “Ornamentation is especially appropriate when motives and phrases are repeated, in the variation passages of the finale of the first Krommer Concerto, for example. This movement provides a perfect opportunity for the performer to add something new.” In the Baroque period, ornamentation was a regular feature of slow movements, which were notated very sparingly by Bach and his contemporaries, in the expectation that the artist would create his own elaborations. By the Classical era, Mr. Klein points out, composers were expressing their own thoughts in slow movements, and performers were not expected to add much ornamentation.

Mr. Klein has added cadenzas to the first Krommer concerto and to the Hummel Variations, neither of which included cadenzas in their original versions. His ornaments and additions present a couple of notes, including a high G and a low A, that were not common or even possible on oboes of the early 19th century. Mr. Klein believes that if those notes had been available to performers of the time, they would have used them in their own interpolations of the basic scores. “Ornaments must fit the style of the music,” he says, “but as long as an artist keeps the style of the composer’s time in mind, he should feel free to play the music in the way he thinks it sounds best.”

Andrea Lamoreaux is Programming Executive at Fine Arts Station WFMT-FM in Chicago.

Album Details

Total Time: 56:13

Recorded: June 17–19, 1998 at the studios of ICN-Polyart, Prague, Czech Republic

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Konrad Strauss

Cover: watercolor by Jack Simmerling

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Andrea Lamoreaux

© 1999 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 045