Store

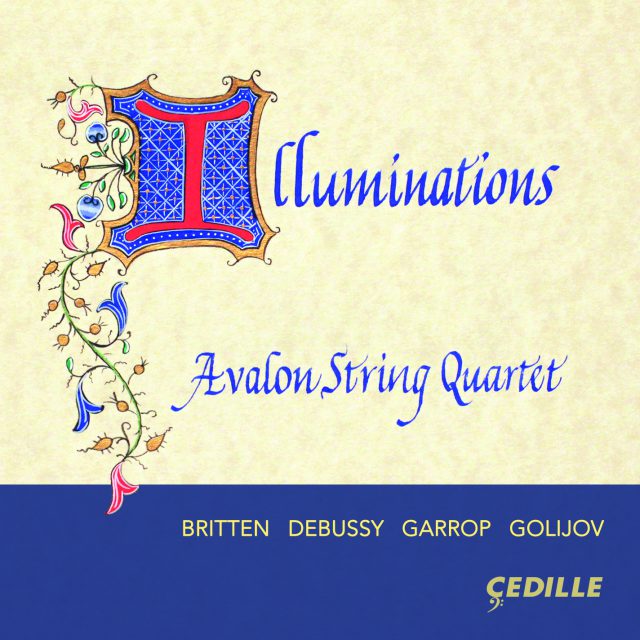

The Avalon String Quartet “a remarkably fine ensemble” (The Strad), makes its Cedille Records debut with an irresistible program of captivating works by Claude Debussy, Benjamin Britten, Osvaldo Golijov, and rising American composer Stacy Garrop.

The ensemble presents the world-premiere recording of Garrop’s String Quartet No. 4, “Illuminations,” a tantalizing, Pictures at an Exhibition style tour of spectacular illustrations from an ornate medieval manuscript. Debussy’s lush, exotic String Quartet in G minor unfolds through iridescent quasi- orchestral textures. Golijov’s lyrical, deeply moving Tenebrae (Latin for “shadows”) pays tender tribute to the earth, depicted in its remote celestial beauty, haunted by undertones of human discord. Britten’s youthful, energetic Three Divertimenti and Alla Marcia are alluring studies in inventiveness and perpetual motion.

Preview Excerpts

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918)

String Quartet in G minor, Op. 10

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976)

Three Divertimenti

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976)

Alla Marcia

STACY GARROP (b. 1969)

String Quartet No. 4: Illuminations

OSVALDO GOLIJOV (b. 1960)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletIlluminations

Notes by Brian Hart

Claude Debussy: String Quartet in G minor, Op. 10 (1893)

Debussy’s only mature composition with a key signature and opus number shows how he could take a genre with a long tradition and do something new with it. The quartet’s four movements follow conventional forms on the surface, but the composer treats them very freely. The first movement, for example, is in sonata form, but instead of developing the themes in the manner of Beethoven, Debussy subjects them to constant variation and transformation, even in the exposition and recapitulation. In addition, while the first movement is in G minor, he sets the principal theme in the phrygian mode on G.

When Debussy wrote this quartet, he was attempting to win the favor of members of the Société Nationale de Musique, an influential performance outlet. The Société Nationale was then dominated by former students of César Franck. Following their teacher’s example, the Franckistes, as they were known, made much use of a procedure known as cyclicism, in which a theme introduced in the first movement reappears throughout subsequent movements to unify the piece. Accordingly, Debussy adopts this procedure in his quartet, but again does so in a fairly liberal manner. Whereas Franck’s pupils typically recalled previous material in more-or-less original form, Debussy has the theme heard at the opening of Movement I return in continually evolving versions in the second and fourth movements (it does not appear in the third). Debussy’s free treatment both of Franck’s cyclic procedure and traditional quartet structure upset listeners at the Société Nationale when his quartet premiered there at the end of 1893; chagrined by the response, the composer never wrote another.

The second movement, the most original, is a captivating scherzo: a two-measure motive derived from the cyclic theme (first heard in the viola) repeats over and over against layers of pizzicato accompaniments. Here the composer is inspired by Balinese gamelan music, which he had heard a few years earlier at the 1889 Paris World Exposition. The slow movement is deeply meditative and expressive. The finale takes the first movement’s cyclic theme and its derivative in the second movement and subjects both to further transformations.

Benjamin Britten: Three Divertimenti (1933, rev. 1936) and Alla marcia (1933)

While best known for his vocal and choral works and operas, Britten wrote striking chamber music, including three string quartets (the last of them premiered shortly after his death in 1976). In 1933, while attending the Royal College of Music, the 19-year old composer started a suite entitled Alla Quartetto Serioso: “Go play, boy, play” (a line from Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale). Britten struggled with this work and completed only three of its projected five movements. He revised them in 1936 as his Three Divertimenti. After a poorly received performance — marked by “sniggers and cold silence,” according to his diary — Britten shelved the work, and it was not heard again in his lifetime.

The whimsical March opens with glissandi, followed by a swaggering tune. The shadowy Waltz features repeated notes propelled forward by the dance rhythm and is marked by extremes of register. Where that movement is restrained, the Burlesque is flamboyant, dominated by a perpetual motion theme with a slightly exotic flavor. Even at this early stage, Britten shows a self-assured command of string writing, using open fifths and octaves, open strings, double and triple stops, and special effects throughout.

Britten wrote Alla marcia in two days in February 1933; it received a private hearing later in the month at the home of Britten’s teacher, Frank Bridge, with Bridge on the viola. The piece was initially inspired by a film of a German children’s story. Britten thought of making it the first movement of Alla Quartetto Serioso but subsequently replaced it with what became the opening March of the Three Divertimenti. In 1939 he reused material from Alla marcia in the penultimate movement (“Parade”) of his orchestral song cycle Les Illuminations.

Like the March of the Three Divertimenti, Alla marcia is a parody. A pizzicato vamp in the cello introduces a jaunty, angular melody in the violin, moving flippantly in triplets over an increasingly heavy accompaniment. At its height, the melody moves in octaves over pedals of fourths and fifths, sometimes in cross rhythms. The march dies away at the end.

Osvaldo Golijov: Tenebrae (2000)

Golijov has become one of the most prominent composers of the early 21st century. Born in Argentina in 1960, he was raised in Israel and studied in the United States. In celebrated compositions such as La Pasión según San Marcos (The Passion According to Saint Mark, 2000) and the opera Ainadamar (Fountain of Tears, 2003), he mixes folk and popular styles of Latin American, Caribbean, Spanish, and Sephardic cultures with assorted contemporary techniques.

Golijov originally composed Tenebrae for clarinet, soprano, and string quartet but later revised it for string quartet alone. On his website (osvaldogolijov.com), the composer states:

I wrote Tenebrae as a consequence of witnessing two contrasting realities in a short period of time in September 2000. I was in Israel at the start of the new wave of violence [. . .] and a week later I took my son to the new planetarium in New York, where we could see the Earth as a beautiful blue dot in space. I wanted to write a piece that could be listened to from different perspectives. That is, if one chooses to listen to it ‘from afar,’ the music would probably offer a ‘beautiful’ surface but, from a metaphorically closer distance, one could hear that, beneath that surface, the music is full of pain. I lifted some of the haunting melismas from Couperin’s Troisième Leçon de Tenebrae [sic], using them as sources for loops, and wrote new interludes between them, always within a pulsating, vibrating, aerial texture. The compositional challenge was to write music that would sound as an orbiting spaceship that never touches ground.

Tenebrae, Latin for “darkness,” refers to the Catholic services held on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, the days commemorating the somber events of Jesus’s arrest, crucifixion, and burial before light and joy return on Easter Sunday. François Couperin’s Trois leçons de ténèbres (Three Lessons of Tenebrae, published between 1713 and 1717) set passages from the Lamentations of Jeremiah for two voices and basso continuo. In each lesson, the sections of the text are prefaced by letters of the Hebrew alphabet, which Couperin sets as vocal melismas; Golijov incorporates those of the Third Lesson into his work.

Tenebrae divides into four continuous sections. The first places a wistful melody against soft tremolo accompaniment. In the second, the instruments play notated passages ad libitum as the music becomes distinctly Middle Eastern in sound; constant pulsating figures (again played ad lib.) sound against a chant-like melody, played “infinitely slow, as being in orbit.” This third section achieves a short climax (notated “biting”), then dies away. The fourth section reprises the opening theme while the violins add a peaceful melody over it. Each of Couperin’s lessons ends with an invocation to Jerusalem; likewise, in the original vocal version of Tenebrae, the violin melody sets the word “Yrushalem.”

– Brian Hart, Professor of Music History, Northern Illinois University

Stacy Garrop: String Quartet No. 4: Illuminations (2011)

Notes by Susan Yasillo and Stacy Garrop

Stacy Garrop’s String Quartet No. 4: Illuminations was inspired by five illuminated pages from a medieval Book known as The Hours of Catherine of Cleves. Books of Hours, the most prolific book form of the late Middle Ages, are prayer books for lay people that enable a person to participate privately in the daily round of prayers and devotions that were recited originally only by monks and priests. The main text of a Book of Hours contains a cycle of daily devotions comprising psalms, lessons from scriptures, hymns, collects, and other prayers. Books of Hours did not have page numbers or indexes, the illuminations (or illustrations) enabled the owner to quickly find the text needed for reciting the prayers. The quality and number of illuminations, often using silver and gold, depended upon the patron’s ability to pay.

Catherine (1417–1476), duchess of Guelders and countess of Zutphen, commissioned her Book of Hours and received it around 1442. Today her Book of Hours is considered the masterpiece of the finest (albeit anonymous) Dutch illuminator of the late Middle Ages. The Hours of Catherine of Cleves is also among the finest Books of Hours in the collection of the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City.

To evoke the experience of reading Cleves’s Book of Hours, the composer approached the work similarly to Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. As in Mussorgsky’s work, the audience follows the reader as he or she opens the book, studies and reflects on the five illuminations, and then closes the book at the end of prayer. Following are brief descriptions of the five illuminations represented in the quartet:

The first illumination shows Catherine kneeling before the Virgin and Child praying, “O, Mother of God, have mercy on me.” The setting may be the

castle chapel in Cleves and the statue at the top center of the panel may be of St. Nicholas, the patron saint of the Cleves castle. Musical angels are on the battlements and coats of arms of Catherine’s ancestors surround the illumination. The composer based this movement on the Gregorian Chant “Ave Maria.”

Three angels start to sing the hymn “Te Deum Laudamus” (although this hymn is not employed in the quartet). The beginning words are on the banderol, “We praise thee, O God.” This illumination likely refers to the preceding one, now missing, of the Annunciation to St. Anne (Mother-to-be of the Virgin Mary). The large open pea pods of the border are symbols of fertility. For this plate, the composer envisioned a harmonious chorus of angels and achieved this sound using high string harmonics.

This illumination shows Christ carrying the cross with Simon of Cyrene, St. John, and the Virgin Mary behind him. Hanging from Christ’s waist are two blocks of wood with nails that torture his ankles and feet. St. Veronica appears on the left side margin. The music for this plate invokes the sound of Christ’s feet as he slowly walks to his final destination.

This illumination of Hell begins the Office of the Dead. People prayed often for protection from, and to prepare for, death — which could be sudden and unexpected due to the plague and new strains of influenza. This frightening

entrance to hell has one mouth with talons and pointed teeth leading to a second fiery mouth with creatures boiling souls in the depths of hell. Around the picture, souls are being tormented, while at the top a third mouth of fire is heating caldrons into which souls are cast. At the bottom is a green creature spewing out scrolls with the names of the seven deadly sins. The music captures both the ghoulish glee of the demons, as they carry out their tortures, and the wailing of the unfortunate souls.

The Trinity, similar in posture and dress, sits on a throne with the Father on the left, the Son in the middle, and the Holy Ghost on the right. The banderoles address death and salvation. The text on this page begins with

the plea, “Oh, God, come to my assistance.” In the middle of the text a prayer begins, “Glory be to the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.” The nine different colored angels around the throne are thought to represent different orders of celestial beings. The composer sought to represent the majesty and benevolence of the Trinity, represented by a string of three-note chords (one note for each member).

Album Details

Total Time: 71:25

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: December 15-18, 2014, at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts at the University of Chicago

Cover Art: Fiona Graham-Flynn, 2015

Graphic Design: Nancy Bieschke

Publishers: Britten: © 1983 Boosey and Hawkes for Three Divertimenti and Alla Marcia

Garrop: © 2011 Theodore Presser Company for String Quartet No. 4: Illuminations

Golijov: © 2002 Boosey and Hawkes for Tenebrae

© 2015 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 156