Store

The esteemed Vermeer Quartet joins forces with phenomenal oboist Alex Klein in three pillars of 20th-century British chamber music. Benjamin Britten’s spellbinding Phantasy Quartet (1932) for oboe, violin, viola, and cello was his first work to gain international recognition. This passionate piece displays elements that became hallmarks of his unique style.

Noteworthy for its sublime balance between oboe and strings, Arthur Bliss’s gorgeous Quintet for Oboe and String Quartet (1927) deftly blends diverse styles and influences, concluding with the ingenious use of an Irish jig. In a fitting finale, the Vermeer plays Britten’s last major work, the String Quartet No. 3 (1975). The New York Times says of the valedictory piece, “Every episode. . . seems to emanate from some mystical realm.”

Preview Excerpts

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976)

ARTHUR BLISS (1891–1975)

Quintet for Oboe and String Quartet

BENJAMIN BRITTEN

String Quartet No. 3, Op. 94

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletBritten & Bliss

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

If it’s true that the basic grouping in chamber music is the string quartet — two violins, viola, and cello — it’s equally true that composers have often sought to vary and enrich the four-string sonority by adding other instruments. Piano-and-strings chamber pieces, which are abundant, represent the overcoming of a special challenge: each creator of a piano trio, quartet, or quintet has had to deal with the reality that the piano can produce more notes, louder, at any given moment than a stringed instrument can. The solution is often to group the strings as a choir in opposition to and rivalry with the keyboard. This sets up a kind of musical dialogue that can be very involving and satisfying both to perform and to hear. When poorly executed, however, either on the original music paper or in concert, the result can be a small-scale piano concerto with the strings overshadowed.

Composers who have chosen to add a wind player to their string complement have added an instrument that plays a single line instead of powerful chords, and they have the added resource of tone colors that strongly contrast with, and stand apart from, the sonority of the strings. The light evanescence of a flute, the penetrating notes of an oboe, or the mellow sound of a clarinet bring an extra dimension to a work’s overall timbre when surrounded and contrasted with shimmering violins and the rich tones of the viola and cello. Individual melodic lines can intertwine freely, and five voices can combine in harmony or emphatic unison as easily as four.

Circumstances, of course, play a big part in the choice of instrumentation for any chamber work. If your wife is one of the most famous pianists in Europe, as Robert Schumann’s was, you’ll probably write chamber music that involves her instrument (especially if it’s an instrument close to your own heart, too). If you’re a pianist yourself, as Shostakovich was, and your string-playing colleagues want a piece you can all perform together, you’ll gladly oblige with a Piano Quintet. And when a commission comes from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, one of the most influential figures in the history of American chamber music, you’ll be happy to accommodate what she has in mind. That happened to Arthur Bliss (not yet Sir) in 1926, and it must have made him even happier to learn that Coolidge intended his new work for oboe and string quartet for his fellow-countryman, the distinguished English oboist Leon Goossens (who introduced both of the works for oboe and strings on this CD).

Sometimes singled out as the successor to Elgar, whose music strongly influenced him, Bliss was educated at traditional British schools (Rugby, followed by Cambridge University) rather than London’s music conservatories — although he did spend a year at the Royal College of Music before serving in the Army during World War I. After the war, he disdained further education in favor of practical experience as a composer, and a strong pointer to his future came in the 1920s when he began writing and arranging music for London theatrical productions. This endeavor is paralleled in his later years by his numerous film scores (including Things to Come) and his music for the ballet, Checkmate: he was stimulated by the extra-musical factors involved in stage and film music. Another famous piece is his Colour Symphony. He was also noted as a writer of music for choirs; his choral symphony, Morning Heroes, from 1930, was characterized by Bliss biographer Hugo Cole as “one of the most deeply personal of [his] works… after more than ten years, [he] at last exorcised his memories of the war.”

Bliss spent most of the World War II years as an official at the BBC, received a knighthood in 1950, and was named Master of the Queen’s Music in 1953, a post that required him to write music for ceremonial and official occasions. Earlier in his life, in the 1920s and 30s, he spent extended periods in the United States, where he met his wife, Trudy, and was also introduced to Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. A wealthy patron of chamber-music performances, at the Library of Congress and elsewhere, Coolidge believed in encouraging the composers and performers of her own time. Bliss’s autobiography notes that she was unique “in actually knowing a great deal about music, in being able to play it, and in recognizing what an artist stands for, and so treating him as a friendly colleague.” The Quintet for Oboe and Strings was premiered at a Coolidge-sponsored festival in Venice in 1927, by Goossens and the Venetian Quartet. It’s a lively and tuneful work that exploits the various tone-colors of the oboe to the fullest: lyrical singing to staccato jumping. There are numerous tempo shifts in the first two movements. The first, marked “Assai sostenuto” — Rather Sustained — to begin, is a kind of pastorale punctuated by an “Allegro assai agitato” — Lively and Rather Agitated — section that gives the strings a clamorous voice in the proceedings. The relaxed Andante pace that opens the second movement is once again contrasted with a livelier midsection. The jolly finale has one pace throughout: Vivace, one of the fastest standard musical tempos. Dancing motives and propulsive rhythms reach a fun-filled climax as the five players quote a traditional Irish tune called “Connolly’s Jig.”

Born in 1891, Bliss lived into his 84th year, dying in 1975 just one year before his younger and better-known English contemporary, Benjamin Britten (b. 1913). Britten’s impact on the musical life of his country and his century was profound. Like most great composers, he started young — there’s an astounding list of Britten juvenilia. He was 14 when he began studies with noted composer Frank Bridge, who befriended him in addition to teaching, and let him experiment while insisting that he learn the basics. From Bridge and from his own inclination, Britten acquired a reverence for predecessors including Haydn, Mahler, and especially Purcell, whose voice is apparent in one of his most famous pieces, The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra: Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Purcell, and in his Second String Quartet of 1945. Early on, with Bridge’s encouragement, Britten developed a confidence in his own compositional voice, and resisted trends in 20th-century composition that he found uncongenial, most notably serialism. Although 12-tone elements appear in some of his music, it wasn’t his path, and his style stays mostly within tonal realms – albeit with the tonality often obscured, and with high doses of dissonance.

This CD contains one of Britten’s first major successes, the Phantasy Quartet of 1932, and his last major composition of any type, the String Quartet No. 3 of 1975. Between these landmarks, the composer made his mark in virtually every area of concert and theater music. The sensationally successful 1945 premiere of Peter Grimes signaled the resurrection of English opera in the years immediately following World War II. It would be the first in a string of successful stage works, including a number designed for small ensembles, amateur groups, and children. His success with opera, and with the song-cycles created for his partner, tenor Peter Pears, would lead to a perception that he was basically a vocal composer, a judgment that unjustly omits his orchestral scores and the solo-instrumental works he wrote for cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, guitarist Julian Bream, harpist Osian Ellis, and others. The singing element of his output, however, cannot be denied or ignored. It includes what is possibly his greatest work, the War Requiem, a score for soloists, chorus, and orchestra that declares his lifelong pacifism in no uncertain terms: it is a powerful indictment of “war, and the pity of war,” to quote Wilfred Owen, the poet whose World War I verses are the basis of half of the Requiem’s libretto (the rest coming from the traditional Latin Requiem Mass).

In addition to pacifism, another theme strongly addressed by Britten’s music is that of the outsider, the misfit individual pitted against a conventional society, as in Peter Grimes, or the sensitive child misunderstood by his adult keepers, in The Turn of the Screw, the evocative and haunting opera based on the Henry James novella. Though successful as a composer, conductor, and founder and impresario of the Aldeburgh Festival, Britten perceived himself as an outsider, not mainly because of his unpopular stance (especially during World War II) as a pacifist and conscientious objector, but because of his homosexuality, which could be partially accepted in the case of his relationship to Pears, but verged on the unacceptable in his attraction to young boys. There were many levels in Britten’s personality, and a number of them he tried to keep hidden, letting them emerge only in the undertones of his music.

After the tutelage with Frank Bridge, as a teenager perhaps not yet excessively troubled by the conflicts that would enter his life later, Britten enrolled at the Royal College of Music and found academic life a bit stifling, the professors’ conservative attitudes boring. Perhaps as a diversion, in the fall of 1932, coming up on age 19, he decided to enter a work for the Cobbett Chamber Music Prize: a Phantasy Quartet for oboe, violin, viola, and cello. Anyone exploring English chamber music of the early 20th century couldn’t fail to notice the recurrence of compositions with the word Phantasy in their titles, by Vaughan Williams, Holst, John Ireland, and Bridge, among others. No secret dream cult, these composers were all responding to the particular challenge offered by the musical scholar Walter Wilson Cobbett, who believed that chamber music had evolved to a great extent from the 17th-century genre of the fantasia. The characteristic style of the fantasia was variety within unity: Baroque fantasies are relatively brief, single-movement, improvisatory pieces broken up into several sections that are both related and contrasted. Cobbett wanted to make the fantasy an important factor in his hoped-for revival of 20th-century chamber music. He offered a prize for one-movement works that lasted about 12 minutes and offered instrumental parts of equal musical interest for each player.

Given Britten’s fascination with the music of Purcell, this concept was guaranteed to appeal to him. Purcell wrote a number of fantasies for viol consort, but Britten’s idea was to combine three modern stringed instruments with the distinctive timbre of the oboe. The work is laid out in seven linked sections of contrasting tempos that reproduce the feeling of a Baroque fantasia. The Andante Alla Marcia sections that begin and end the piece give the march rhythm to the string players, with special prominence for the cello, supporting a lyrical oboe melody. These sections surround a modified sonata-form structure with an expository section, marked Allegro giusto — Lively with strict rhythm — followed by an Andante interlude, a “Con Fuoco” (fiery) passage, a central slow section, and a brief “Piu agitato” (more agitated). The heart of the piece, the central slow passage is a kind of pastorale, but every measure is engaging and fanciful. First performed over the BBC in 1933 by Leon Goossens and members of the International String Quartet, the Phantasy was then presented at the 1934 festival of the prestigious International Society for Contemporary Music, “an unusual honor for a 19-year-old composer,” critic Steven Ledbetter has noted.

Written in 1911, Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice came back to international, and controversial, prominence in the early 1970s via a film and an opera. The film was praised in some quarters for its evocative visual effects and its soundtrack drawn from the music of Gustav Mahler. It was reviled elsewhere as a distortion of the original story. The opera, composed by Britten in 1974, cast Peter Pears as Gustav von Aschenbach, the German academic who takes a vacation in Venice just as the city is being overcome by a cholera epidemic. Traveling alone, isolated from his surroundings, misunderstanding the warnings he receives from mysterious figures encountered briefly — all portrayed by the same singer in different guises — Aschenbach can focus only on his obsession with Tadzio, an ethereally beautiful boy visiting Venice with his parents and lodging in the same hotel. In both film and opera, the role of Tadzio is a silent one. In the opera, he is portrayed by a dancer. The impulse toward pedophilia is quite open in both adaptations, although it is more veiled in the film. In the opera, Aschenbach’s final statement in Act 1 is an impassioned “I love you.”

Repulsion toward pedophilia makes Death in Venice controversial in any of its settings. Nevertheless, the opera is one of Britten’s finest works: a powerful drama encased in remarkable music. It is less about forbidden love than about obsession and isolation, the dreams of a man yearning for human contact and threatened by both physical death and moral collapse.

Recovering from heart surgery in 1975, Britten struggled to complete a third string quartet, a long-delayed successor to works he’d written in 1941 (on commission from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, while he and Pears were visiting the United States) and 1945 (a work written as a tribute to Purcell). The third work in the genre was intended for the Amadeus String Quartet, which gave the premiere in 1976, two weeks after the composer’s death, at Aldeburgh’s Snape Maltings Concert Hall. The quartet is dedicated to the musician, writer, and broadcaster Hans Keller, who encouraged Britten to write it during his difficult recovery from surgery. The Amadeus players also contributed their thoughts to the finished work.

The quartet is linked to Death in Venice via the introduction to the final movement, headed “La Serenissima: Recitative and Passacaglia.” Britten wrote this finale during his last visit to Venice (“La Serenissima”), a city he loved. The quartet is laid out in five movements, the kind of arch form favored by Bartók that sets up a central movement surrounded by opening and closing movements whose moods or themes are related, and second and fourth movements similarly linked to each other. Each of Britten’s movements has a subtitle. The first is Duets: here motives are presented by two instruments at a time, and we hear all six possible pairings among the four instruments. The melodic elements anticipate the Passacaglia theme of the finale. We reach next an Ostinato: a short, energetic and abrupt movement based on a four-note pattern that leaps across three octaves. The pattern is continually repeated: ostinato means “reiterated” in Italian musical terminology. An emotional high point of the work is the soulful “Solo,” spotlighting the first violin with singing lines. It has been suggested that this movement memorializes Dmitri Shostakovich, who died in 1975, and who had been a close friend and artistic colleague. The key of the Solo is C Major, implying a kind of serenity: perhaps also a sense of resignation, toward Shostakovich’s recent death and toward what Britten must have regarded as his own imminent demise. Britten and Shostakovich admired each other a great deal, and perhaps had feelings of “outsider” kinship: each composer sought to express forbidden yearnings, whether political or personal, through music.

Shostakovich is even more powerfully recalled in the “Burlesque” fourth movement, whose biting tones recall the sarcastic Scherzos of so many of the Russian composer’s symphonies and string quartets. The atmosphere of the Third String Quartet as a whole may be regarded as a response to Shostakovich’s Quartets Nos. 12–15, which are intense emotional outpourings veiled in complex musical structures.

The finale opens with quotations from Death in Venice: a gentle water-motif Barcarolle is stated by the cello, then the second violin recalls the theme the opera associates with Aschenbach’s longing for Tadzio. A pizzicato passage for the first violin recalls another operatic scene, called “Games of Apollo,” after which the viola quotes a theme associated with Aschenbach’s line, “When the sirocco blows, nothing delights me.” The sirocco, a wind current prevalent in the Mediterranean and North Africa, is used to imply the spread of cholera throughout Venice. These lines having been established, the instruments join together to quote Aschenbach’s tortured statement of “I love you.” This is the end of the “Recitative” portion of the finale. From here, the passacaglia begins in C Major in the cello. The key evolves into E Major, a prominent key in the opera used to characterize Aschenbach. There is an air of mystery about this finale, as it seems to pose the great question: what is death?

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

Album Details

Total Time: 62:08

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone Design: Melanie Germond

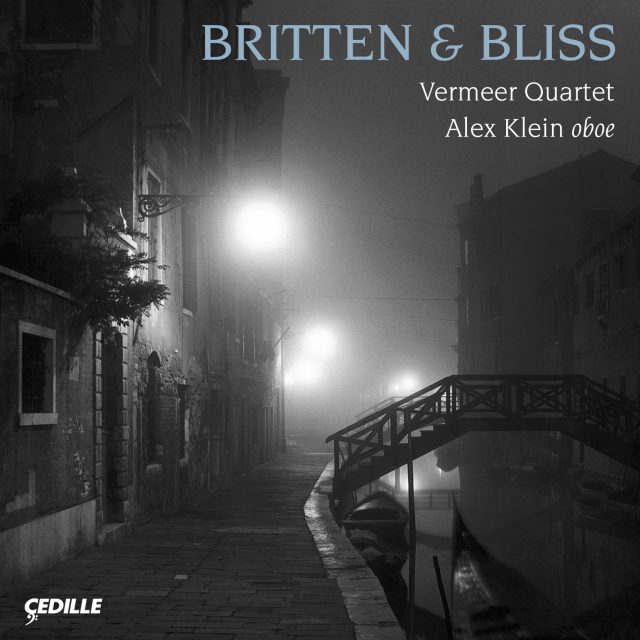

Cover Photo: Venice, Italy ca. 1950 by Ferruccio Leiss, © Alinari Archives/CORBIS

Recorded: October 3 (Bliss) & 4 (Britten Phantasy Quartet), 2005 and April 25-26, 2006 (Britten Quartet No. 3) at WFMT-Chicago

Publishers:

Britten: © 1934 for the Phantasy Quartet and © 1977 for the 3rd String Quartet

Faber Music c/o Boosey and Hawkes Bliss: © 1927 Oxford University Press (NY)

© 2006 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 093