| Subtotal | $12.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.23 |

| Total | $13.23 |

Store

Store

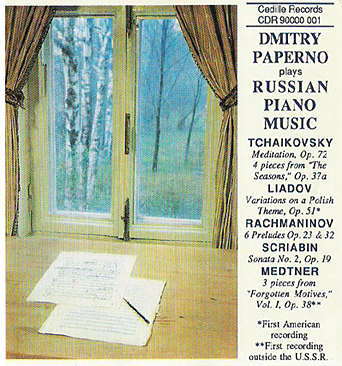

Dmitry Paperno Plays Russian Piano Music

A sublimely sensitive and powerful pianist, Paperno dusts off some rarely displayed musical gems in an all-Russian recital. Rarities include Tchaikovsky’s Meditation, Op. 72, No. 5; Liadov’s Variations on a Polish Theme, Op. 51; and three pieces from Medtner’s; Forgotten Motives,” Vol. 1, Op. 38. Even Scriabin’s Sonata No. 2, Op. 19, and two of the six Rachmaninoff preludes on the program are relatively neglected.

Preview Excerpts

PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

Four Pieces from "The Seasons", Op. 37a

ANATOLY LIADOV (1855-1914)

SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

Six Preludes Op. 23 & 32

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1871–1915)

Sonata No. 2, Op. 19, "Sonata-Fantasy"

NIKOLAI MEDTNER (1880-1951)

Three pieces from "Forgotten Motives" Vol. I, Op. 38

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDmitry Paperno plays Russian Piano Music

Notes by Dmitry Paperno

The purpose of this project was not only to offer a program of Russian piano music, but also to represent in it two lesser-known yet great and totally different composers: Anatoli Liadov and Nikolai Medtner. Even the solo piano music of Tchaikovsky, despite the enduring popularity of his B-flat minor concerto, is played far too infrequently. This recording also offers some relatively neglected compositions of Sergei Rachmaninov (the Preludes Op. 23, No. 10 and Op. 32, No. 11) and Alexander Scriabin, musicians who made their names writing for and performing on the keyboard.

Tchaikovsky (1840-1893): Meditation, Op. 72, No. 5, D major

Hearing this, the most significant piece from Tchaikovsky’s last piano opus, with its overall dignity and pantheistic spirit reaching, at times, the very height of rapture makes it hard to understand how the composer could take his own life only a few months later. “Meditation” is dedicated to V.I. Safonov, then director of the Moscow Conservatory and teacher of Scriabin and Medtner.

Tchaikovsky: Four Pieces from “The Seasons,” Op. 37a

At the end of 1875, Tchaikovsky received a commission from the St. Petersburg Magazine, Nuvellist to produce a short piano piece for each month of the following year. The year 1876 was relatively calm for Tchaikovsky but immediately preceded two fateful events in his life: the beginning of his entirely-postal, yet enduring relationship with the rich widow, Nadezhda von Meck and his highly unfortunate marriage to Antonina Milyukov.

August’s “Harvest Song” suggests farmhands working extremely quickly, although perhaps they take a break during the beautifully contrasted Tranquillo section. September’s majestic movement (“The Hunt”) displays harmonies and phrasing appropriate to the horns of the Chase; As with “August,” September’s stirring opening and concluding sections are contrasted by a lyrical middle. Unlike the preceding two pieces, October’s wistful Autumn Song maintains its melancholy disposition throughout. November’s catchy “Troika,” a favorite encore piece for Rachmaninov, constantly gathers momentum as it moves from the initial theme, to a grazioso middle section, to a series of dotted sixteenth notes which lead into and continue with the first theme’s return.

Liadov (1855-1914): Variations on a Polish Theme, Op. 51, A-Flat major

Anatoli Liadov, favorite student of Rimsky-Korsakov and teacher of Prokofiev and Miaskovsky, was a composer of strong Russian orientation, great mastery, and refined taste – qualities which pervade all genres of his creative output from popular symphonic pictures (e.g., “Enchanted Lake,” “Kikimora”) to charming piano miniatures (e.g., Preludes, Bagatelles). “Variations on a Polish Theme” is an exquisitely crafted cycle of different moods and pianistic textures. The work blends most naturally traditions of Liadov’s Russian predecessors from the “Mighty Five” and the obvious voice of Chopin. The latter influence appears so strong at times (the Theme; several Chopinesque variations, both virtuosic and lyrical; the “Krakowiak” Polish dance form of the final variation) that one might wonder whether Liadov simply forgot to make an inscription on the title page: “Homage a Chopin…”

Rachmaninov (1873-1943): Six Preludes Op. 23 & 32

Three opus numbers form Rachmaninov’s brilliant set of 24 preludes. Under Op. 3, we find only one prelude in C-sharp minor. Although the piece paved the way for his popularity in the United States, Rachmaninov quickly grew tired of being called “Mr. C-sharp!” Ten preludes, assembled under Op. 23 and dedicated to Rachmaninov’s older cousin and teacher, the remarkable Russian musician and educator A. Siloti (who also taught my teacher, A. Goldenweiser), and 12 works listed in Op. 32 round out the set. Although the 24 preludes present vastly differing technical challenges and reflect a wide range of human moods, they have as a common element the goal of portraying the beauty of Russian nature, which Rachmaninov loved so dearly.

G-flat major, Op. 23, No. 10 – The first prelude presented here may be counted, along with the more popular D and E-flat major preludes from the same opus, among Rachmaninov’s inspired “Spring” preludes: one can almost see the boundless, flowing Russian fields and meadows that moved the composer so. It may well be more than just coincidence that in all three preludes a peaceful recapitulation follows a more dramatic middle section, as with a man achieving contentment after having been infatuated with the experience of becoming one with nature. A short, charming coda lowers the curtain on this vision of spring.

B minor, Op. 32, No. 10 – a sad, mournful song gradually turns (after a powerful culmination suggesting trombones and trumpets) into a tragic, even funereal outburst of despair as a remote knell tolls in the distance. The opening song returns only to descend into a somber low register. The piece’s remarkably fresh closing alternation of major and minor completes the impression of anguish and hopelessness.

B major, Op. 32, No. 11 – a distinctively restrained triple meter dance interspersed with several short, pensive stops. One of Rachmaninov’s few “dancing” preludes, the piece exhibits a very flexible harmonic and rhythmical structure.

G-sharp minor, Op. 32, No. 12 – This little masterpiece is perhaps the most popular of the six preludes represented here. As with many of the preludes, it presents a long melodic line against a persistent background of “handbells.” Devoid of any trace of sentimentality, the piece constitutes a tasteful example of what Pushkin called “Light sadness.”

G major, Op. 32, No. 5 – Another musical picture of spring, this prelude is so serene that, instead of providing a sustained middle section, Rachmaninov simply deviates to G minor for several measures. During the recapitulation, the melody ascends higher than before, allowing for a very gradual, seemingly reluctant descent. The rhythmically accompanying quintuplets continue all through the piece, creating a softly shifting sensation. Three simple closing G major chords emphasize the work’s subtle purity.

C minor, Op. 23, No. 7 – This impetuous stream, typical of the young Rachmaninov, is in many ways a smaller soul-mate of the popular 2nd piano concerto, having been written at the same time and in the same key.

Scriabin (1872-1915): Sonata No. 2 Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy”

Scriabin’s intense creative course (which lasted little more than twenty-five years) like Beethoven’s, can be clearly divided into three periods. When one compares Scriabin’s early works with his later opuses, it is hard to believe that they are the product of the same composer. The two-movement Sonata-Fantasy is one of the most poetic creations of the young Scriabin. Mature in form, the piece presents wonderfully spontaneous and youthful impressions of the elemental majesty of the sea.

The probing, questioning theme that opens the first movement creates a feeling of contemplative tranquility while, at the same time, amorphously yearning for a mysterious summons. The short opening motif, a kind of call to which the piece constantly returns, becomes the work’s principal image. The second theme, is broad and lyrical, awash with waves of rich, ornamental sound. The young composer’s astounding mastery of polyphony and polyrhythm are especially in evidence here. According to Scriabin’s conception, the Andante first part, composed in Genoa, depicts a southern night at the seashore; and the Presto second movement, written in the Crimea, conveys the violent spaciousness of the sea. This idea forms the basis for the whole rising and falling, constantly moving mass of sound that comprises the finale. Only for a moment, with the appearance of the movement’s second theme, do we hear an intonation of human suffering, but the elements carry everything off…

Medtner (1880-1951): Three pieces from “Forgotten Motives,” Vol. I, Op. 38

The last of the three great Moscovite pianist-composers represented on this disc, Nikolai Medtner is unfortunately much less known than Scriabin and Rachmaninov. A composer primarily of piano and vocal music, Medtner created the genre called “Skazka” or “Fairy Tale” – a form of lyrical-narrative piano miniature. Medtner’s works combine melodically rich, heart-to-heart musical language with a sense of profound concentration and overall intellect. But it is Medtner’s penchant for polyphonic and rhythmic invention that ultimately insures his highest rank as a composer (my teacher, A. Goldenweiser had even numbered Medtner among the 10 greatest composers of all time!). As a pianist, Medtner was an outstanding interpreter of his own music as well as that of composers from the classical period, most notably Beethoven.

Medtner composed his 3 volume cycle of “Forgotten Motives” during the winter of 1919/1920, soon after the Russian revolution. The Medtners had settled temporarily in a primitive house in a village outside of starving Moscow, with no electricity or running water. The difficult winter turned out to be extremely fruitful for Medtner, who organized hundreds of pages of sketches, spending many long evenings at the poorly tuned piano dressed in a quilted jacket and Valenki (tough Russian felt boots). It is hard to believe that the inspired music that makes up the 3-volume “Forgotten Motives” was largely assembled, composed, and refined under such circumstances. The Medtners left Russia in 1921 eventually settling in England in 1936. One should mention the friendly interest Rachmaninov took in his fellow Russian musician which helped Medtner through his difficult years of exile. Nikolai Medtner died in London in 1951.

Op. 38, No. 6, “Canzona Serenata” – This enchanting song begins by quoting the brilliant discovery that runs through all 8 of the opus 38 pieces: an 8-measure leitmotiv of magical inspiration. The song that ensues is so natural and sincere that one might easily believe it had come from the popular 19th century Russian genre of the “urban romance.” After a more virtuosic “quasi Cadenza” episode, the Canzona flows back into the recurring 8-bar leitmotiv which beautifully frames the whole piece.

Op. 38, No. 7, “Danza Silvestra” – This lively work affords an intriguing example of Medtner’s imagination and formal mastery. Very different images, some lyrical, some fantastic, some downright peculiar, pass across the constant background of the dance. Medtner employs a most unusual rhythmical formula through much of the piece: 8 sixteenth notes in the right hand over quarter note triplets in the left give these passages an oddly shifting feel. The leitmotiv undergoes an astonishing metamorphosis, making it hardly recognizable; yet it is still there carrying out its thematic function all through the piece. Danza’s quiet ending quotes the second theme of the Sonata Reminiscenza, Op. 38, No. 1, as Medtner crafts a beautiful attacca transition to the last piece in the cycle.

Op. 38, No. 8, “Alla Reminiscenza” – A truly unique work, No. 8 is based entirely on the main motif of the cycle and the unusual 8 against 3 rhythmic formula employed in the Danza. This fascinating miniature begins serenely, gradually ascending into higher and higher registers and increasing dynamically (sempre crescendo) as it builds to an extremely powerful culmination, a kind of triumphal hymn to Nature or perhaps to Medtner’s beloved Russia which was still alive despite the tragic ordeal She had endured…

— Dmitry Paperno

Album Details

Total Time: 71:01

Recorded: June 14 & 16, 1989 at WFMT Chicago

Executive Producer: James Ginsburg

Producers: James Ginsburg & Bill Maylone

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Tchaikovskys work table at his home in Klin

Notes: Dmitry Paperno

© 1989 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 001