Store

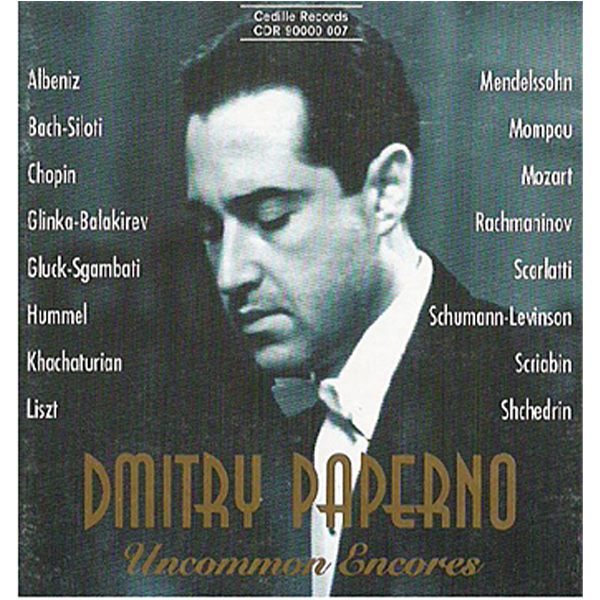

When the French say “Encore!” they actually mean “Not again!” And that’s how jaded record collectors might feel toward another CD of piano encores. (The French yell “bis” to demand an extra piece at the end of a recital.) Yet Dmitry Paperno’s Uncommon Encores explodes the notion that an encores album means showy musical chestnuts, roasted too many times over.

Russian-born Paperno delivers deep, powerful performances of 16 lesser-recorded piano miniatures. He magnifies and reveals these rich musical microcosms with a three-dimensional pianism that takes advantage of the instrument’s full sonorities.

A rarity is the Cancione y Danza No. 1 by Federico Mompou, the Spanish (Catalan) composer who specialized in small-scale piano pieces. “Many of his pastels are of an extraordinary haunting . . . elegance,” wrote Lionel Salter in the New Grove Dictionary (1980). Mompou’s “fondness of ostinato figures and bell sound often lends an incantatory quality to his poetic evocations.”

Even the one Rachmaninoff piece, the Polichinelle, Op. 3, No. 4, is seldom heard.

A beguiling, spiritual performance of Siloti’s transcription of Bach’s Prelude in B minor opens the program. Scarlatti’s Sonata in B minor is beautiful and dramatic, with a sunny radiance and eternally fresh-sounding melodies. Sgambati’s transcription of Gluck’s Mélodie d’Orfée is achingly lovely and seems perfect for a tenderly romantic movie scene. Particularly interesting in Shchedrin’s suspenseful yet jazzy Basso Ostinato.

Russian pianist and teacher Leah Levinson’s transcription of Schumann’s song “Der Nussbaum” (The Nut Tree) receives its first-ever recording. “An amazing achievement for a one-piece composer,” Paperno writes in the liner notes. “She gave me the piece as soon as she finally wrote it down in the early 1960s.”

Paperno’s liner notes, like the recording, are uncommon, informative and quite touching. A mature artist, Paperno offers stimulating first-person accounts of his relationships with the pieces and their performance challenges. Paperno tells of his first visit with Shchedrin, “my closest friend from my years in what used to be the USSR.” Unable to find a copy of the popular Basso Ostinato score, Paperno went to the composer’s Moscow apartment and came away with a personally inscribed copy.

Preview Excerpts

J.S. BACH (1685-1750) / tr. Siloti

DOMENICO SCARLATTI (1685-1757)

C. W. GLUCK (1714-1787) / tr. Sgambati

J. N. HUMMEL (1778-1837)

FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847)

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) / tr. Levinson

FREDERIC CHOPIN (1810-1849)

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

ISAAC ALBENIZ (1860-1909)

FEDERICO MOMPOU (1893-1987)

MIKHAIL GLINKA (1804-1857) / tr. Balakirev

SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915)

ARAM KHACHATURIAN (1903-1978)

RODION SHCHEDRIN (b. 1932)

W. A. MOZART (1756-1791)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThoughts On The Program

Notes by Dmitry Paperno

The source for the Bach-Siloti Prelude in B minor is not the Prelude & Fugue in E minor from Book I of the Well Tempered Clavier, as is commonly believed, but a left hand finger study in the same key from “The Little Clavier Book” (which Bach later elaborated into the tenth of the 48 Preludes & Fugues). It is a rare example of a piano transcription of a keyboard work. Siloti was a student of Liszt and teacher of my teacher, Alexander Goldenweiser. He took the sixteenth notes from the left hand, transferred them to the upper voice, and transformed the eighth notes Bach placed in the right hand into a singing melodic line for the left. Siloti probably chose to write his arrangement in B minor so that the left hand solo would wind up in a solid baritone register. This, by the way, was a favorite encore piece of Emil Gilels.

Following Michelangeli’s awe-inspiring performance of Schumann’s Piano Concerto at the 1955 Chopin Competition in Warsaw [Paperno was a prize winner; Michelangeli was one of the judges], he played Scarlatti’s B minor sonata along with a sonata in C minor as encores which just left listeners speechless. (After the concert all the enigmatic, self-deprecating Italian would say to enthralled backstage visitors was “You never heard Lipatti!”) I soon added both pieces to my concert repertoire and, during the 1960s, presented a set of four Scarlatti sonatas along with several Busoni Bach transcriptions (including the D minor Chaconne) as the first half of one of my regular programs. This rarely performed Sonata is an unjustly neglected testament to Scarlatti’s genius.

My initial interest in Giovanni Sgambati’s transcription of Gluck’s Melody for Two Flutes from Orpheus stems from a recording by Rachmaninov — an irresistible performance by a powerful pianistic personality. This is a tricky work, however; until the past decade it did not seem worth the effort to learn it for concert performance. The key to playing this piece is balancing three distinct, intricately woven layers of sound. Sgambati was a student of Liszt; not as brilliant as Siloti, but this beautiful piece should ensure his place in the annals of piano transcription.

I obtained the score of Hummel’s Rondo in E-flat in Warsaw in 1955 and recorded the piece for Moscow Radio a few years later. My playing then was faster, more superfluous. This is not the kind of piece from which one can expect much depth, but it demonstrates a lovely, early Viennese, classical approach to the clavier and great imagination in the development of the Rondo form. An outstanding student of Mozart, Hummel’s chamber music enjoyed considerable popularity a while ago (I remember playing his Quintet in E flat, Op. 87 with a group of Chicago Symphony musicians in Orchestra Hall in 1977). Today, except for the Trumpet Concerto, his music seems forgotten (even his once standard cadenzas for Mozart’s piano concertos are rarely used). One can only hope that this challenging piece will be heard in our concert halls more often.

Unlike Hummel’s Rondo, Mendelssohn’s Rondo Capriccioso remains a popular concert piece. One of Mendelssohn’s best piano works, it is typical of his lighter music, alternating the spritely Rondo subject with very warm, sincere slower sections. The main theme is in the same style and key — E minor — as the Midsummer Night’s Dream overture, conjuring fantastic elfin creatures. Yet there is always a delicious hint of melancholy in the background whenever the E minor theme returns. Also noteworthy are the highly Mendelssohnesque E major opening and dramatic ending. I have been playing this piece since I was a teenager enjoying my fast fingers at Moscow’s Central Music School in the 1940s, but there is definitely much more to this music than I realized then.

Leah (leea) Levinson was an assistant to Alexander Goldenweiser at the Moscow Conservatory. A prize winner at the 1932 All Russian Competition, she was a successful performer with a wide repertoire until she broke her shoulder in a severe auto accident not long after the competition. Now in her mid-eighties, Ms. Levinson remains active in Moscow’s musical life. For her only transcription, she chose one of Schumann’s best songs. From Myrthen, Op. 25, it is a typically romantic story with a nut-tree (Nussbaum) describing its bittersweet life. Levinson’s transcription is an amazing achievement for a one-piece composer; it even boasts canonic passages. She gave me the piece as soon as she finally wrote it down in the early 1960s.

Mazurkas were special for Chopin. Extremely nationalistic and intertwined with Polish national history (“Cannons in flowers,” Schumann called them), Chopin’s Mazurkas convey every side of Polish character. (Significantly, Chopin’s last composition was the harmonically fragile Mazurka in F minor, which he played only days before his death.) The big late Mazurkas like the one I play here are so rich in content that they could easily be called Ballades. This piece expresses extreme sadness, even hopelessness. There are moments in the B major middle section when it becomes nostalgic only to give way to a recapitulation and especially a coda full of despair. So much is contained in such a short period of time. The piece is comparable only with miniature masterpieces by Schumann and Scriabin in the strong impact it makes on the listener. This Mazurka was part of my program at the Chopin Competition. Unlike many works I played when I was younger, my approach to this one has changed little since then.

While Liszt transcribed for solo piano many songs by other composers, Die Loreley is the only self-song transcription of his I know. The music follows precisely the events of Heinrich Heine’s beautiful poem about a character common to folk legends throughout Europe dating back to the sirens of Greek mythology. Loreley (Rusalka in Russia, Ondine in France, and Switezianka in Poland) is the gorgeous maiden who sits on a rock in the middle of the river luring sailors who try to approach her to their deaths in stormy waters. You really need to know the content of Heine’s ballade to appreciate this piece fully because every line is conveyed in the music.

Cordoba comes from a set of pieces by Albeniz called “Songs of Spain,” each one describing a different Spanish province. The slow introduction to this beautiful piece describes the stillness of a Spanish night. One moment in particular strikes me because it comes extremely close to the sound of Russian Orthodox choir music. This is apparently coincidental, although there are definitely some links between Spanish and Russian music (starting with two Spanish Overtures by Glinka). The faster part of Cordoba is like a melancholic serenade accompanied by guitar. Its victorious major key culmination is interrupted at its peak. The piece never gets all that fast, however, because Spanish music always contains a feeling of dignity and melancholy.

I discovered Federico Mompou’s Song and Dance No. 1 when Michelangeli played it as an encore following his unforgettable 1955 Warsaw recital. I found the Mompou score in Warsaw because no one played this music in Moscow at the time. Though born in Barcelona, Mompou’s ancestry and musical heritage belong more to Catalonia than to Spain. The slow song constantly shifts between major and minor, creating a feeling of leisurely uncertainty. The piece displays a free kind of singing calling for a unique brand of rubato (there are no bar lines). The prevailing feeling is one of siesta or relaxation with an inevitably melancholic background. With no double bar to mark its ending, the piece concludes by fading away into nothingness.

The Lark is a beautiful song by Glinka describing bittersweet thoughts awakened by the vision of this solitary bird. Balakirev’s transcription is popular among advanced Russian piano students, but the work presents a serious task for the mature performer who must make it sound as even, well balanced, and naturally flowing as possible. I taught the piece several times but did not play it myself until the early 1980s when I began to use it as an encore. I have noticed that the work has an amazing affect on Oriental listeners and students perhaps because it is such an exquisite example of sheer sentimentality.

I have been playing Rachmaninov’s Polichinelle Op. 3, No. 4 since I was a teenager during the second world war. The work is not too difficult, but to be bright and pushy enough to bring out the music’s bravura nature takes some imagination. As with Liszt’s Die Loreley, Polichinelle concerns a character common to many national folk legends: known as Pulchinello in Italy, Petrouchka in Russia, and Punch in England (Polichinelle is French), he is a mischievous marionette or clown-like figure. Polichinelle is an unjustly neglected piece from the same early Rachmaninov opus as the famous C sharp minor prelude (which the composer ultimately tired of hearing).

The irresistible Op. 38 Waltz is one of the best pieces from Scriabin’s fertile middle period. I first heard it in a recital by Vladimir Sofronitzky given at the end of 1943, a time when few concert artists graced Moscow’s stages (the Central School of Music had just returned to the city following its evacuation). The piece made an unforgettable impression on me. Goldenweiser assigned it to me the next year when I was only fifteen, even though it really requires more emotional as well as musical maturity. This is my third recording of the piece: I taped it for Moscow Radio in the late 1950s and again for an MHS LP in the late 1970s. Though titled Waltz, the piece is really a dream which becomes ecstatic toward the end and then disappears forever. It has a unique rhythmical structure: phrases come not in groups of four or eight measures as is usual, but in three-bar sections. The only analog I can think of is a little played Waltz-Fantasy by Glinka (which shows just how many-sided and creative this Russian genius was).

Khachaturian’s Toccata is the oldest encore piece in my repertoire and the one I have played more than any other over the years. When I began serious concertizing, I would almost always use the piece as an encore unless the entire recital was devoted to a single composer like Schumann or Chopin. I would also play it after performances of Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto [Paperno was the first non-Shostakovich to perform the work]. Composed in 1932 while Khachaturian was still a student of Miaskovsky, it is a brilliant, masterfully constructed, very Armenian piece. It is very effective as a show piece for piano even though it sounds much tougher than it is.

Rodion Shchedrin is my closest friend from my years in what used to be the USSR. In the early 1960s, I decided to play three of Shchedrin’s shorter piano pieces: Basso Ostinato and the very funny Humoresque and Imitating Albeniz. Basso Ostinato was so popular at the time that I could not find a copy of the score anywhere, so I had no choice but to contact Shchedrin directly. I went to his home in the same building on Gorky Street where Emil Gilels and other big shots lived (Shchedrin, a rising star, lived there with his wife, the legendary ballerina Maya Plisetskaya). We chatted for a couple of hours, I played Imitating Albeniz for him, and he gave me the score to Basso Ostinato with a very kind inscription. That’s how our now close friendship started. Shchedrin’s early pieces from the 1950s and 60s like Basso Ostinato and the hilarious Obstreperous Street Tunes for orchestra signaled the emergence of a fresh and brilliant new talent in Russia. In the West he is best known for the inventive 1967 Carmen Suite which, like all his ballets, he wrote for his wife.

I decided to end the program with the Mozart Andante cantabile for three reasons:

- I wanted to frame the program with the two greatest composers — Bach and Mozart.

- This was my teacher, Alexander Goldenweiser’s favorite last encore during his performing career.

- A very special friend of mine, Mikhail Iglitsky, a brilliant physicist and mathematician who entered the Leningrad Conservatory as a conducting student in his thirties and died at the age of forty, a few years after graduating, said that if he had to save only one piece of music it would be this Andante. Those words have always stuck with me.

I used to play the whole sonata on concert programs, but after my friend died in 1969 I began playing just the Andante as an encore. I have used the piece especially frequently since emigrating because it is one of the last ties to my musical life in Russia. Like my teacher, I always end my concerts with it. Words cannot express the divine perfection of this music. It speaks of eternal matters such as life and death with almost childlike simplicity and kindness as only Mozart could do.

Album Details

Total Time: 71:24

Recorded: July 10 & 11, 1991 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover photo: Paperno at the Moscow Conservatory, 1964

Design: Robert J. Salm

Notes: Dmitry Paperno

© 1992 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 007