Store

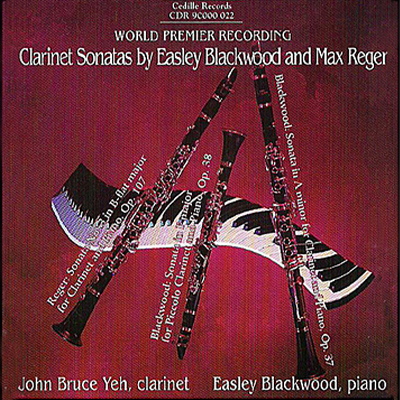

It’s hard to find noteworthy music for clarinet and piano, not to mention accessible contemporary compositions. Composer and pianist Easley Blackwood expands the repertoire with two accessible yet substantial works written in 1994 and receiving their recording debuts on this CD. Both Blackwood works were written for John Bruce Yeh, assistant principal clarinetist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, who performs on the album with Blackwood.

“These are pieces worth playing, worth mastering,” Yeh says. “Blackwood has perfect understanding of what the instrument does well and how to make the best of it.”

Most clarinet and piano works by major composers are for the B-flat clarinet, so Blackwood took a different tack by writing for the Clarinet in A and the E-flat piccolo clarinet. His richly melodic, high-stepping Sonata in A minor for Clarinet and Piano moves with a ballet-like rhythmic verve. His festive Sonatina in F major for Piccolo Clarinet, Op. 38 explores the uncharted lyrical side of an instrument usually relegated to humorous or grotesque effects in large orchestral works. “There is no repertoire whatever for piano and E-flat clarinet — at least to my knowledge,” Blackwood writes in the CD booklet.

Best-known for his somber, sprawling organ works, Max Reger reveals surprisingly witty and tender sides to his musical personality in the Sonata No. 3 in B-flat major, Op. 107 (1909), and early 20th century piece that echoes the bygone German Romantic tradition. The sonata had long been a favorite of Yeh, who convinced Blackwood, a musical collaborator for some 17 years, to consider adding it to his repertoire. One reason the sonata coexists so well alongside Blackwood’s is that they’re “similar in harmonic idiom,” Blackwood says.

Yeh became a member of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1977 at age 19. Two years later, Sir George Solti appointed him assistant principal clarinetist. He also performs as soloist with orchestras in the US and Europe and with prestigious chamber ensembles such as the Guarneri String Quartet and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.

Preview Excerpts

EASLEY BLACKWOOD (b. 1933)

Sonata in A minor, Op. 37

MAX REGER (1873-1916)

Sonata No. 3 in B-flat major, Op. 107

EASLEY BLACKWOOD

Sonatina in F major for Piccolo Clarinet, Op. 38

Artists

Program Notes

View Album BookletSonata Op. 37 and Sonatina Op. 38

Notes by Easley Blackwood

Both pieces were written between June 30 and October 24, 1994 — first the Sonata, and then two weeks later, the Sonatina. They were composed for Mr. Yeh, with whom I have had a stimulating musical relationship for over 17 years. It seems rather strange that there should be so little for clarinet and piano in the standard repertoire. The only works of this genre by well-known composers are the Duo of Weber, the two Sonatas of Brahms, a Sonata by Saint-Saens, three Sonatas by Reger, the Sonata by Poulenc, and the Rhapsody of Debussy.

My Sonata is written for clarinet in A for two reasons: most of the aforementioned works are for clarinet in B-flat, suggesting that a gap might be filled; also, the additional low note furnished by the clarinet in A is very useful. My Sonata is in a conservative tonalidiom, which, for the past seventeen years, I have found more convivial than conventional, academic modernism. In the Sonata, I use the entire tonal harmonic vocabulary, including advanced altered chords and chromatic resolutions, such as those found in Franck, Strauss, and Rachmaninoff, but sparingly — only at dramatic or expressive moments.

The first movement is in sonata-allegro form, although with an unusual key arrangement, in that the first and second themes in the exposition are in A minor and B major, respectively. Another salient feature of the movement is its relatively frequent use of augmented triads to effect modulations between relatively remote keys. This is especially noticeable in the connection between A minor and B major in the exposition, and from B major back to A minor via a different route from the exposition to the development. In the recapitulation, the second theme is presented in A major. The movement closes with a brief coda, at the beginning of which augmented triads are again prominent.

The second movement is a series of gently contrasting episodes that bear some resemblance to a theme and variations, especially at the close of each episode. Each section is in a different mode and key; however the modes are used strictly only at the outset and a later return, while the central portions are freer. The scheme is as follows: Theme, in C-sharp minor Aeolian mode, a slow march; Variation 1, F major Mixolydian mode, rather quicker; Variation 2, C minor Dorian, slow and pensive; Variation 3, E major Lydian, a minuet; and Variation 4, C-sharp minor Phrygian, a barcarolle.

The last movement is a sonata-rondo, again featuring an unusual key scheme. The first statement of the refrain is in A minor, the first couplet is in C-sharp major, and the next version of the refrain is in A-sharp minor, a variation on the first featuring invertible counterpoint. The development is characterized by a more complex chromaticism; following this, the couplet returns in D major. The work concludes with a brief reference to the refrain and a coda.

The Sonatina posed a special challenge, for there is no repertoire whatever for piano and E-flat clarinet (piccolo clarinet) — at least to my knowledge. Furthermore, the E-flat clarinet is generally associated with humor or grotesquerie, such as the sardonic solo during the “bad-dream” episode of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, or the outlandish solo in Copland’s El Salon Mexico. But the instrument is adaptable to a lyric style as well, especially in the lower register, and it generally permits a higher tessitura, although this can become a dangerous endurance problem for the performer. In order that the Sonata and the Sonatina should be in contrasting styles, the latter uses a simpler harmonic vocabulary and a less intricate formal arrangement.

The Sonatina’s first movement is a conventional sonata form whose first and second themes are in F major and C major, respectively, in the exposition. The development does not make use of the more remote keys, tonics being confined to A minor, E minor, G major, and C major. The second movement is in an A-B-A form; outer sections are in A-flat major, and the central section is in F minor. The finale is a rondo that uses a rather more intricate key scheme, but largely avoids chromatic progressions. Overall, the Sonatina is not unlike the three Sonatinas for violin and piano of Schubert, although the key successions of the last movement are rather more like Schubert’s song Die Sterne (D. 939, 1828).

Sonata No. 3, Op. 107 by Max Reger

Reger’s Sonata No. 3, Op. 107, was completed in 1909, seven years before his untimely death in 1916 at age 43. In 1909, this unjustly neglected composer was enjoying enormous prestige. From 1907 to 1911, he was professor of composition and director of music at Leipzig University. At the same time, he composed more than twenty large-scale works, while maintaining active careers as both conductor and pianist. Although best known and esteemed for his organ works, he composed in every genre, save for opera. As a composer, Reger is part of the German Romantic lineage that includes Shumann, Wagner, Brahms, Strauss, and Schoenberg in his pre-atonal period, and the influence of these can be plainly sensed in Reger’s music. He is also consciously indebted to J.S. Bach, especially in his works for piano and organ.

One factor that aided Reger in his prolific creativity was his ability to work on several different compositions simultaneously. For example, part of the day might be given to advancing on a new work — sketching out the principle melodies, the bass line, and an overview of the form. Next, he might take a work already in this state, and add details regarding the harmony. Finally he would go on to yet another work that needed only the working out of the intricate voicings and textures that are so characteristic of his style. I strongly suspect that the Third Clarinet Sonata was written in these three stages.

The Sonata is a large, ambitious work that should certainly be regarded as among the best of the repertoire for clarinet and piano. Its harmonic idiom is complex and chromatic, but never diffuse or incoherent. Formally, it is entirely traditional; the first movement is in sonata-allegro form, the second is a scherzo and trio, the third is a ternery song form, and the finale is a sonata-rondo. Of particular interest is the use in later movements of material heard earlier. For example, portions of the scherzo are inconspicuously quoted in the slow movement. Of more importance are the expressive transformations of a six-note motive that forms the principal part of the first movement’s second theme. Transformations of this nature play a significant part in works of composers often characterized as post-Wagnerian. The six-note motive is recalled once in the third movement at a particularly expressive moment, and then assumes greater importance in the Sonata’s finale, where it is presented first as a pastoral melody, then a stately chorale, and finally a lilting dance. The work closes with a coda that is drawn, first from the slow movement, and then from the ending of both the exposition and recapitulation of the first movement, which in turn contains a final statement of the six-note motive.

— Easley Blackwood

Album Details

Total Time: 67:00

© 1995 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 022