Store

“Among the most impressive period-performance ensembles around today” (Musical America), Haymarket Opera Company presents early-18th-century master Leonardo Vinci’s rare operatic gem, Artaserse (1730). A prominent figure of the Neapolitan School of opera, whose work influenced composers such as Johann Adolph Hasse and Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Vinci’s three-act opera seria centers on the Persian prince, Artaserse, who must bring his father’s murderer to justice amidst betrayal, deceit, and mistaken identity.

Celebrated as a classic in its time with multiple revivals into the 1750s, Artaserse features a libretto by Italian poet and librettist Pietro Metastasio, who was regarded as one of the most important librettists of 18th-century Europe. The opera, comprising 28 arias, one duet, four orchestrally accompanied recitatives, and a final chorus, offers dazzling vocal writing and highlights Vinci’s talent for dramatic intrigue.

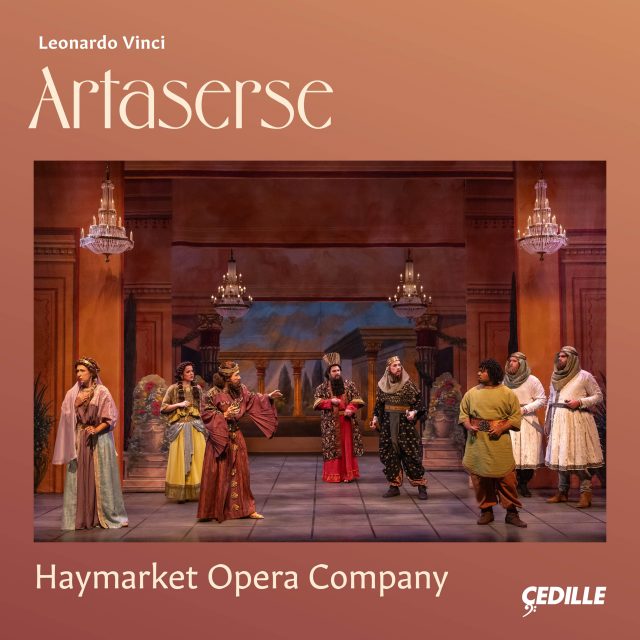

Featuring top international and regional vocalists and skilled period instrumentalists, who “proved themselves fully prepared to engage with the drama through… spectacular flights of virtuosic vocalism” (Opera Magazine), Artaserse received its American premiere by the Haymarket Opera Company in June 2025 in Jarvis Opera Hall at DePaul University.

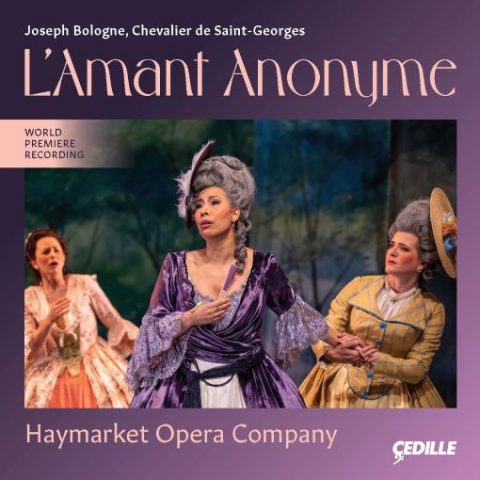

In 2023, Cedille Records released the Haymarket Opera Company’s debut album: the world-premiere recording of Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges’ only surviving opera, L’Amant Anonyme (The Anonymous Lover). The recording has been praised for “restoring Bologne to his rightful stature . . . [with] luxury casting, including the 2005 Cardiff Singer of the World laureate Nicole Cabell in the lead role” (Gramophone) and as a “recording that does this marvelous score full justice . . . a triumph in every respect” (Fanfare).

Since its founding in 2010, Haymarket Opera Company has enriched Chicago and the Midwest’s musical scene with critically acclaimed performances of 17th- and 18th-century operas and oratorios, played on period instruments, with historically informed singing and staging. It has presented more than 30 productions: both fully staged operas and concert presentations.

Artaserse was produced by James Ginsburg and engineered by Bill Maylone and Eric Arunas. The album was recorded on July 3 and 5–7, 2025, in the Sasha and Eugene Jarvis Opera Hall at DePaul University in Chicago.

Artaserse is made possible by a generous lead gift from Nancy Dehmlow; sponsorships from Patricia Kenney & Gregory O’Leary, Lori Julian for the Julian Family Foundation, and Glory & Lynn Witherspoon; and the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Fund for Vocal Recordings at Cedille Records

Preview Excerpts

LEONARDO VINCI (1690 – 1730)

Act 1

Artists

1: Haymarket Opera Company

Program Notes

Download Album BookletMestastasio, Opera Seria, and Convention

Notes by Louise K. Stein

With his exciting Artaserse, composer Leonardo Vinci (1690–1730) invites us into the fascinating world of early 18th-century opera seria and the elegant libretti of Pietro Metastasio (1698–1782, born Pietro Antonio Domenico Trapassi), whose texts were clothed in new music perhaps a thousand times by hundreds of composers throughout Europe (excepting France). Some libretti were taken up more than once by the same composer (Niccolò Jommelli thrice set Didone abbandonata, for example). Artaserse, first produced with Vinci’s music in Rome in 1730 and last produced with music by Charles Lucas in 1840, was one of the five most often set among Metastasio’s 26 dramas. Despite the public’s appetite for novelty, Vinci’s Artaserse was revered as a classic with revival productions into the 1750s.

The literary aesthetic for the newly dignified dramma per musica emerged from the late 17th-century discussions of the Arcadian Academy in Rome. Above all, the Arcadians rejected the highly entertaining Mestastasio, Opera Seria, and Convention licentiousness, irrationality, and delightfully illogical “abuses” in 17th-century Italian opera. Trips to the underworld, low-born characters, and the antics of comic servants had no place in the reformed libretti. Deaths and murders (aside from those occurring in battle) were moved offstage. Spells cast in magic chambers, inferno scenes, and deities riding on clouds were purged, and visual spectacle beyond luxurious costumes, wigs, swords, headdresses, and throne rooms was limited to royal celebrations or simulated natural phenomena (especially tempests at sea).

Metastasio’s libretti fictionalize episodes from ancient history (Roman, Persian, Indian, or Chinese) with heroic schemes derived from 17th-century French classical drama. In the typical three-act structure, Act One is devoted to exposition of the plot, characters, and central conflicts; Act Two develops the intrigue and adds myriad complications; and Act Three provides a dramatic climax followed by a rapid denouement to a tasteful closure. The action takes place in locations of close proximity and, preferably, concludes within 24 hours. Overall, the operas offer idealized tragedies that, nevertheless, resolve in happy endings (the conventional lieto fine).

Each of Metastasio’s libretti presents six or seven characters belonging to the highest social elite, all of them connected by bonds of affection, whether through erotic love, family, fraternity, or close friendship. Sudden conflicts test these bonds, especially when romantic love runs afoul of duty to father, ruler, or country. The characters tend to resemble larger-than-life figurines whom the audience comes to know facet by facet, aria by aria. The hero may have a tragic flaw due to an inherited situation or immobile political circumstance but never shows moral weakness. The hero’s innate nobility is unquestioned, even as he endures cruelly false accusations while trapped in a seemingly unresolvable conflict with an oppositional foil or villain. The plots depend on descriptions of offstage violence, but onstage violence is out of the question. Accusations, misunderstandings, threats, and rejections by lovers, friends, confidants, and allies stir the plot, but only the villain commits ignoble acts. The villainy in Metastasio’s ingenious Artaserse is multiplied through the despicable plotting of the coconspirators, Artabano and Megabise.

The conventions of opera seria were never inflexible, but their replication in opera after opera facilitated the rapid spread of the genre from Naples, Rome, and Venice to court and commercial theaters across Europe (again, excepting France). With flattering portraits of “enlightened” rulers and rational despots whose magnanimity resolves all conflicts honorably, the operas supported the social and political status quo, projecting submission to the ruler by those not in command, the obedience of children to a father, and steadfastness in love and friendship.

Literary and musical conventions erected a supportive structure within which composers and singers exercised their creativity. Singers were the absolute prime movers and wielded considerable power. In their arias, the seria characters reflect on or react to what has just happened or been revealed in recitative. Most seria arias before ca. 1760 are in the da capo form, but composers also manipulated or subverted the da capo convention in various ways to enhance the drama. Of course, every 18th-century production required a great deal of improvisation, so even the most jaded audience could be surprised or pleased by the particularities of a given musical setting or vocal display.

At top theaters, a composer might make suggestions regarding the cast. In any case, he certainly knew in advance which singers would have which roles so he could tailor the parts to suit their preferences and voices. It was expected that the protagonists would be assigned an equal number of arias, although this convention could hardly prevail in practice, given singers’ preferences, contractual demands, and the fraught negotiations theater managers engaged in to attract and assure the very best performers. Arias were often revised or replaced with newly composed music or even substitute arias from a singer’s repertory (the notorious “suitcase” arias). Singers took pride both in owning the arias composed for them and in performing new ones. Top singers generally did not perform arias composed for a competitor, although the most famous of the castrati, Carlo Broschi “Farinelli,” was flattered on one occasion when the brash upstart Gaetano Majorano “Caff arelli” dared to insert Farinelli’s fabulous “Son qual nave che agitata” (composed by Farinelli’s brother, Riccardo) in a 1731 Artaserse pasticcio for Milan.

Whether planned for the entertainment of a court audience or an urban public, from the time of its invention in the early 17th century, the opera theater was both pillar and mirror of society — the place to see and be seen in many kinds of interaction. Theaters offered audiences considerable freedom (as scholars, including Chicago’s Martha Feldman, have pointed out). Those who could afford to attended the opera almost every night during the season. Police dockets, private letters, hilarious satires, diplomatic posts, travelers’ reports, and juicy gossip columns all reveal the myriad activities happening before, after, and during the show. But listeners still expected brilliant music and fabulous voices. Luxurious productions of these long seria operas provided audiences with a welcome escape through the imaginative fusion of highly dramatic plots with affectively powerful arias performed with originality by virtuoso singers.

In the years around 1720, when Vinci was working in Naples as a composer of Neapolitan comic opera at the Teatro dei Fiorentini, his experience creating rhythmically lively melodies and simple, clear textures for the comic genre was formative as he shaped a new anti-baroque musical style for serious opera in Naples. The new idiom prioritized beautifully expressive melody and balanced affective saturation with clarity of expression while rejecting outdated baroque extremes, unbalanced irregularity, and heavy counterpoint. Vinci’s first “dramma per musica,” Publio Cornelio Scipione, was assigned a remarkable cast and applauded in a long run of performances following its 1722 premiere in Naples. Two years later, in 1724, Metastasio’s first libretto, Didone abbandonata, was performed with music by Domenico Sarro at Naples’ Teatro di San Bartolomeo — a landmark production for this poetic and musical paradigm shift. Vinci’s own 1726 Didone abbandonata, for Rome, was the first presentation of any of the poet’s dramas in his native city.

Vinci’s Artaserse received its premiere at Rome’s Teatro delle Dame, also known as the Teatro Alibert, on February 4, 1730, and continued its run until it was cut short suddenly on February 21 due to the death of Pope Benedict XIII. Vinci’s was the first setting of Metastasio’s Artaserse libretto, but the libretto was quickly revised for Johann Adolf Hasse, whose version premiered during the same carnival season on February 11 at Venice’s opulent Teatro di San Giovanni Grisostomo. Both productions featured excellent casts, but Hasse’s was a definite cut above, with prima donna Francesca Cuzzoni as Mandane, Nicolino Grimaldi as Artabano, and none other than Carlo Broschi “Farinelli” as the hero, Arbace.

Vinci’s Artaserse offers 28 arias, one duet, four orchestrally accompanied recitatives, and a final chorus. Acting as both composer and impresario at the Teatro delle Dame, Vinci recruited four high-soprano castrati for the season, including Farinelli’s brilliant competitor, Giovanni Carestini as Arbace; the experienced virtuoso Raff aele Signorini as Artaserse; and Giacinto Fontana “Farfallino” as Mandane. Whereas the increasingly famous Carestini continued to sing through the 1750s, Signorini and Fontana were veteran singers nearing the end of their careers. By 1730, Fontana had specialized in singing female roles in Rome for some 20 years. The young tenor, Francesco Tolve (Artabano) performed mostly in Naples, first developing histrionic skill in Neapolitan comic operas at the Teatro dei Fiorentini, where Vinci had worked in his apprentice years. Tolve’s three Roman performances of Vinci’s music in 1729–1730 (in the serenata La contesa de’ numi, Alessandro nell’Indie, and Artaserse) ignited his career as a seria tenor. A few years later, he was even recruited alongside Farinelli by Handel’s Italian competitors in London — the “Opera of the Nobility” — for their 1736–1737 season. Vinci’s striking tenor role for Artabano suggests he knew Tolve to be a vigorous, versatile, and entertaining singer and actor. And, as is so often true in opera before 1800, Artabano’s bizarre villainy ignites some of the opera’s best music.

The action in Artaserse erects scaffolding for the characters’ affective expression. Each section of the libretto opens with a definite action (or report of an action, in the case of the offstage murders of Serse and Dario) calling for an emotional response. For example, after Artabano thrusts his bloody sword into Arbace’s hands, Arbace sings “Fra cento aff ani,” a powerful concitato aria whose string tremolos, large leaps, busy fioriture, and gasping repeated notes project his shock and fear. Less often, the aria response is crafted through mere stereotype, as in Megabise’s “Sogna il guerrier le schiere,” a typical warrior aria with trumpets and horns conveying his blunt reaction to Semira’s rejection.

Two important scene complexes famously demonstrate how Vinci’s choices serve Metastasio’s drama. Before the first of these, the Act One stage set has moved from the open air of a lovely garden into the tighter quarters of an indoor palace room for scenes eight through ten. In these scenes, the characters are brought onstage for recitative revelations: Artabano has killed Artaserse’s brother Dario; Artaserse regrets Artabano’s rash action; Serse was not killed by Dario; and the “true” killer (or so everyone is led to believe) has been arrested carrying a bloody sword.

In scene 11, a disarmed Arbace is falsely accused of murder. He declares his innocence but will not reveal that his father is the true murderer. Artabano (whose secret objective is to secure the throne for his son) suddenly reviles Arbace and demands that Artaserse (king now that both Serse and Dario are dead) condemn him. The accumulated action requires a significant emotional response from Arbace’s friend, the stunned Artaserse, who suddenly finds himself “judge, friend, lover, criminal, and king.” Sensibly, he pauses the action with “Deh, respirar lasciatemi,” a brooding, unsettled G-minor aria with tortured suspensions and lamenting bass gestures.

As the libretto proceeds to dismantle Arbace’s relationships with father, close friend, sister, and lover, Vinci’s characters respond to Arbace in a series of contrasting arias. First, tenor Artabano blasts his son with the concitato “Non ti son padre,” full of wordy G-major fury and strident octave leaps. Next, Arbace’s sister Semira responds with cautious sympathy (she will reconsider once he is declared innocent!) in “Torna innocente e poi,” a lilting F-major siciliana of pastoral innocence with unison violins (flutes in some sources) doubling the vocal melody. At least Mandane, Arbace’s lover, seems appropriately upset (having lost father and brother, she now finds her lover accused of murder). Disorderly emotions render Mandane unable to sing a straightforward da capo aria. Her E-minor presto, “Dimmi che un empio sei,” begins as a rage aria, then develops as an unusual tripartite setting when her romantic longing for Arbace tempers her anger in the second section, until her frustration explodes in a recomposed return in a third section combining music and poetry from both the first two sections.

In the final scene of Act One, deserted Arbace’s dramatic accompanied recitative, “No, che non à la sorte,” introduces a bravura D-major simile aria comparing his emotional agitation to that of a sailor navigating tempests at sea. In the famous “Vo solcando un mar crudele,” Vinci responds to the general poetic topos with elaborate trills in the voice and swirling triplet figures in the violins, then also paints individual words. The primary melody rises and falls for the waves in the “cruel sea”; the wind (vento) blows through an extended melisma; the foundational bass line slides down to suggest ever-unstable Fortune (Fortuna); repeated chords and low horn tones seem to crash against the ship’s hull; and so on. This elaborate virtuoso aria remained enormously popular throughout the 18th century. It was so fully considered Carestini’s that Farinelli politely refused to sing it in Ferrara for a 1731 pasticcio, despite his patron’s request. Carestini carried “Vo solcando” and other Vinci arias from Artaserse with him to London and into Handel’s 1734 Arbace pasticcio.

In Act Two, Artaserse is just learning how to rule. He feels convinced from the start that his friend Arbace is innocent. His grand D-major aria, “Rendimi il caro amico,” reasserts his royal power and confidence in his friendship with Arbace through strong declamation, gallant dotted rhythms, full scoring, and reiterated trumpet calls. Later, however, his errors of judgment set off myriad complications, with attendant aria reactions from his subjects. Worst of all, he mistakenly trusts the scheming Artabano to free Arbace, a son so horrified by his father’s plan for regicide that he marches heroically back to his cell rather than seize the chance for a cowardly escape.

Act Three opens with one of the 18th century’s favorite stage sets — a prison deep inside the royal fortress. In a brilliant stroke, Vinci opens the prison scene with a one-section aria (an arioso or cavatina) whose “Grave e staccato” ritornello sounds a D-minor death march with heavy dotted rhythms and pained suspensions in the violins over passacaglia-like bass figures. A physically weakened Arbace sings “Perchè tarda è mai la morte” within this musical representation of imprisonment. Artaserse enters his cell and convinces Arbace to escape, but as they part, the hero sings “L’onda dal mar diviso,” a fast, brilliant, fully scored D-major simile aria with horns and trumpets. The stellar vocal part in this dancing, triple-meter celebration of friendship is loaded with difficult syncopated leaps, triplets, and challenging fioriture of every kind (another showcase for Carestini). The remainder of Metastasio’s text for Act Three is focused primarily on sentiment, offering each character, and thus each of Vinci’s talented singers, a final aria. Amidst the riches of Vinci’s score, perhaps the most ravishing music belongs to “Tu vuoi ch’io viva o cara,” a slow, lyrical C-major duet with long-breathed melodies begun by Arbace as he reunites with Mandane prior to the extravagant aborted violence and high recitative drama of the final throne room scene. Vinci’s thoroughly delightful music and stunning array of arias in Artaserse sound a brilliant manifestation of Metastasio’s belief that “human passions are the necessary winds with which we navigate this sea that is life.”

© 2025 Louise K. Stein

Louise K. Stein is Emerita Professor of Musicology, Early Modern Studies, and Latin American Studies at the University of Michigan. In 1996, the American Musicological Society honored her with the Noah Greenberg Award for “distinguished contributions to the study and performance of early music.” Her most recent book, The Marqués, the Divas, and the Castrati: Gaspar de Haro y Guzmán and Opera in the Early Modern Spanish Orbit (Oxford, 2024), is available both in print and as an open-access e-book.

Notes by

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Additional Session Engineer Eric Arunas

Recorded

July 3 and 5–7, 2025, Sasha and Eugene Jarvis

Opera Hall at DePaul University (Chicago)

Cover Photo Elliot Mandel

Costume Renderings and Designs Stephanie Cluggish

Graphic Design Bark Design

CDR 90000 242