Store

Store

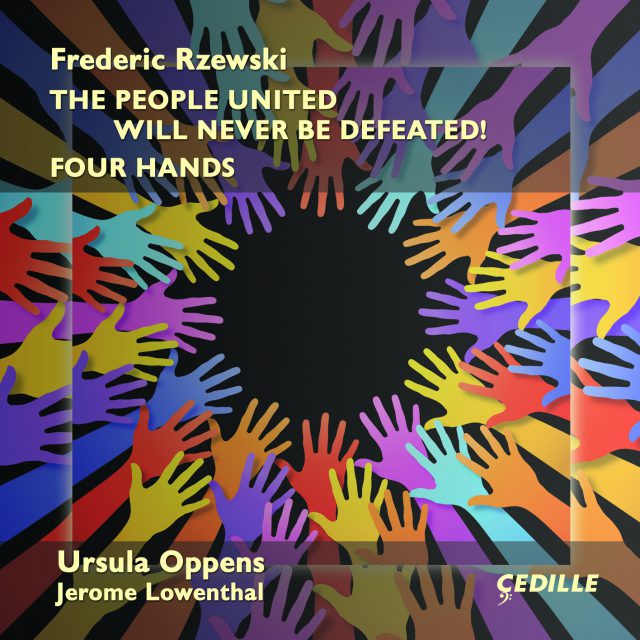

Rzewski: The People United Will Never Be Defeated!

New-music icon Ursula Oppens, who commissioned, premiered, and made the first- recording of maverick American composer Frederic Rzewski’s The People United Will Never Be Defeated!, a remarkable, monumental set of solo piano variations, has re-recorded that landmark 1975 work to mark its 40th anniversary. This riveting, audience-pleasing tour-de-force is a nearly hour-long set of 36 variations on a popular Chilean protest song from the era of Augusto Pinochet’s repressive right-wing military dictatorship. AllMusic.com applauds it as a work “of bewildering and amazing variety, ranging from serialism to jazz to romanticism to the further reaches of the avant-garde and back” and culminating in “a superbly emotional climax.”

Oppens’s world-premiere recording of The People United Will Never Be Defeated! was released in 1978 by Vanguard on analog LP and later reissued on CD. This new recording offers the advantages of Cedille’s 21st-century audiophile production values and an interpretation that benefits from Oppens’s four-decade association with the work. Another bonus is the world-premiere recording of a new Rzewski work, Four Hands, a duet commissioned by and written for Oppens and pianist Jerome Lowenthal, her duet partner on the recording. Fiercely challenging to perform, it leaves the listener “absorbed and exhilarated” (New York Times). Grove Music Online notes that Oppens “is known particularly for the intelligence, technical skill, and warmth she brings to her performances and recordings of contemporary music.” The Washington Post declared, “her rigorous, unforced performances again prove that few pianists of any era can claim a hold on contemporary piano music as she does.” When she performed The People United Will Never Be Defeated! at a 2011 Boston concert, the Boston Musical Intelligencer wrote, “the power and grace of Oppens’s performance was lost on very few.”

The album was produced and engineered by multiple Grammy-winner Judith Sherman. Oppens’s Cedille Records discography includes two Grammy nominees, Oppens plays Carter and Winging It: Piano Music of John Corigliano, and a recording of duo-piano music by Messiaen and Debussy with Jerome Lowenthal.

Preview Excerpts

FREDRIC RZEWSKI (b. 1938)

The People United Will Never Be Defeated!

Four Hands

Artists

Program Notes

View Album BookletRzewski: The People United will Never be Defeated!

Notes by Christian Wolff

Many wonderful pianists have recorded Frederic Rzewski’s 36 Variations on “The People United will Never be Defeated!” The song itself, by Sergio Ortega, is superbly strong. Frederic and I first heard it sung by Inti-Illimani in a concert at Hunter College. The variations explore all of piano history; that’s why so many pianists — like the creatures in Saint-Saens’s Carnival of the Animals — like to play them. History changes, but people need to remain united in recognition of the great varieties among us.

—Ursula Oppens

With the formation in Chile of the Unidad Popular in 1969 and the left coalition under Salvadore Allende, there emerged a new cultural movement of remarkable vitality. Its music drew on the resources of both indigenous folk and classical traditions, and conservatory trained musicians took part together with folk singers. Melodies of popular songs might be harmonized in new, experimental ways and structured with the refinements of distinctive compositions. Or, on the other hand, folk instruments, many of which are native Indian, would be used in compositions based on classical models. The resources of the Western classical tradition were put to use for a music that was truly popular — without being either simplistically primitive or commercially meretricious. The underlying force of this cultural movement was a commitment to the struggle for the socialist transformation of Chile.

Frederic Rzweski’s piano piece, comprising 36 variations, is a tribute to this cultural movement and a musical expression of solidarity with the forces and traditions that inspired and helped shape it. The composition, dated September–October 1975, is dedicated to Ursula Oppens. The song on which the variations are based was written by Sergio Ortega and Quilapayun; it is probably the best-known product of the Chilean New Song Movement. After the coup in 1973, in which Augusto Pinochet toppled Allende’s leftist coalition and replaced it with his dictatorship, this song became a kind of international anthem of the Chilean resistance. In 1991 Pinochet’s repressive regime was replaced by Chile’s current democratically-elected government.

In the context of Rzewski’s own musical background, these variations represent a noteworthy development. Both as a pianist and composer he had been closely involved in the avant-garde and experimental movements of the 1960s. He had worked with, among others, Boulez, Stockhausen, and Cage. By the early 1970s, however (at about the same time as a number of other composers associated with the avant-garde, including Cornelius Cardew, Erhard Grosskopf, and Garrett List), he had started writing music with political subjects, notably the powerful Coming Together. This music included elements that recalled rock and the musics of Terry Riley, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich (open, diatonic or modal sonorities, a steady beat, electric instruments). But because of the political texts associated with it, it expressed a distinctive urgency. It was also at about this time that Rzewski, after considerable experience with improvisation as a soloist and in the group Musical Elettronica Viva, began to associate with jazz musicians such as Anthony Braxton and Steve Lacy. Concurrently, he developed an interest in popular political music, including songs of the Italian left (he had been living much of the time since the 1960s in Rome) and of German socialist Hanns Eisler, the new Latin American music from Cuba and Chile, Puerto Rican folk music in New York, and the songs of Mike Glick.

In the variations many of these elements come together, along with yet others, in a remarkable amalgam. The expansiveness of the piece’s structure, the virtuosity of the piano writing, the use of tonal harmony, all bear some resemblance to Romantic piano music. Yet the large dimension, based on a carefully worked out, intricate underlying structure, also suggests features of avant-garde writing — and many recall the elaborate formal arrangement of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. The piano writing includes explorations of new sonorities, uses of harmonics after a chord attack, plus whistling by the pianist, crying out, and slamming the piano lid — all techniques suggesting experimental music and the free, informal kind of performing sometimes found in blues and jazz. (Some of these optional “effects” do not occur in this performance, however.) Tonality too is used experimentally, as in the combinations of modal writing and the serial-like organization of sets of variations around restricted interval combinations. There are also suggestions of Rsewski’s jazz-related piano improvising.

The variety of elements in the piece is, finally, coordinated and synthesized by both the content and the structure of the whole composition. The content — the meaning and feeling the piece conveys — is an extended projection of the song on which it is based. The music has a kind of program, not literalistic, but mostly suggestive. It is occasionally indicated in the playing directions: “with determination,” “delicate but firm,” “confidently,” “struggling,” “dreamlike, frozen,” “with foreboding,” “recklessly,” “optimistically,” “expansive, with a victorious feeling,” “with energy,” “relentless, uncompromising,” “in a militant manner,” “tenderly, and with hopeful expression.” The music evokes the anguish of struggle and moments of defeat. It includes lyrical and reflective interludes. But these are subordinated to a feeling of confidence and united effort. The Chilean struggle is evoked and linked to kindred movements throughout the world by quotation of and allusion to the Eisler-Brecht “Solidarity Song” and the Italian traditional socialist song, “Bandiera Rossa.”

One further, pervasive aspect of the music’s content is expressed through its structural procedures. These can be seen to represent the force of logic (the logic of history), reason (the reasonableness of justice), and discipline as they focus and liberate creative, revolutionary energies.

The music’s formal logic is too extensive to describe in detail. Its outlines, I think, emerge clearly as one hears the music. The important point is that this musical logic is not an arbitrary, formalist exercise, but is integral to the content of the music. For example, in a detail: the melodies of the songs that are quoted are not just dropped into the music but emerge from its fabric; they derive, in the sequence of their pitch intervals, from the developing variations of the opening “El Pueblo” song. The opening song is set in thirty-six bars, which are followed by thirty-six variations and then as an expanded repetition of the song setting. Throughout the variations there is a continuous cross-referencing of motifs, harmonic procedures, rhythms, and dynamic sequences. These in turn are contained within the organization of the variations. The variations are grouped in six sets of six. The sixth variation of a set, itself in six parts, consists of a summing up of the previous five variations, with a final sixth part of new or transitional material. (It has been suggested that the first five variations of a set make up the fingers of a hand, and the sixth unites them to make a fist.) This procedure is followed rigorously throughout the first four sets of six variations; each of the variations is 24 bars, the first five of a set subdivided equally into 12 plus 12 bars, and the sixth recapitulating each previous variation in four bars plus a final four bars of new material. In the fifth set of variations (tracks 26–31), there is some expansion at the third variation; cadenza-like material appears and the articulation of individual variations is less self-contained, though the sixth variation of the set again clarifies by uniting what preceded. Finally, the sixth set of variations (tracks 32 through 37) becomes a gathering together of elements of all the preceding 30 variations — the overall structure of the piece is thus a reflection of the structure of its constituent parts. In this sixth set, the first variation draws together, in units of four bars each, elements of the first variation of the first set, the first of the second set, the first of the third, and so on. The second to fifth variations of this last set proceed similarly. In the sixth variation of the set, the 36th and last of the entire piece, the preceding five variations are summed up, even as they had been a summation of the preceding 30 variations. Elements of each variation are now compressed into a fraction of a bar. Technically, this is a kind of stretto, the procedure in a fugue that brings the entrances of individual voices closer and closer together, although here the voices (or elements of individual variations) are not overlaid but compressed and juxtaposed in increasingly rapid sequence. The effect is of extraordinary intensification, which, by virtue of the logic of repetition, provides both a clarification and unification. The movement of the whole piece is towards a new unity — an image of popular unity — made up of related but diverse, developing elements (not to be confused with uniformity) coordinated and achieved by a blend or irresistible logic and spontaneous expression.

Christian Wolff is an American composer of experimental classical music.

Four Hands

Notes by Jerome Lowenthal

Traditionally, performers have divided four-hand music into two categories: friendly or unfriendly. At the artistic top of the first category is Schubert’s F minor Fantasy, a masterpiece perfectly cast in the four-hand medium. Beethoven’s notorious arrangement of the Grosse Fuge, in which the composer virtually ignores keyboard reality, leads the unfriendly category. And now, with Frederick Rzewski’s Four Hands, we have a third category: music that neither avoids pianistic problems (like Schubert) nor ignores them (like Beethoven), but rather exploits them so brilliantly that they become the subject of the work. The principal exploitative device is hocket, which the Oxford Dictionary of Music defines as “a device in which rests were introduced into two parts in such a way that a note in one would coincide with a rest in another.” The Oxford author adds: “At the period of the Hocket, composers were eagerly experimenting with all sorts of new-invented devices and apparently this one greatly pleased their innocent minds.”

Mr. Rzewski’s far from innocent use of hocket is in fact wickedly witty and forces the two performers to fall all over each other while playing music of richly allusive substance. The first movement, which contains a Dies Irae quote and a quasi-quotation from the Brahms clarinet quintet, opens with a modulation reminiscent of Prokofieff (second violin concerto) or Taneyev (piano quintet). The second movement seems aleatoric but is in fact constructed on a Webernian tone row that turns back on itself. The finale is a jazzy fugue in which the theme consists of a tone-row and its inversion. Using a wide repertoire of contrapuntal devices, Rzewski recalls Beethoven, Barber, Carter and, not least, Brahms. The words E.M. Forster supplied for the Brahms-Handel fugue could almost be used for the Rzewski: “There was a bee, upon a wall, and it said buzz and that was all and it said buzz and that was all.”

Composed in 2012, Four Hands is dedicated to Ursula Oppens and Jerome Lowenthal.

Album Details

Total Time: 66:48

Producer/Engineer: Judith Sherman

Engineering and Editing Assistant: Jeanne Velonis

Steinway Piano Technicians: Li Li Dong and Joel Bernache

Recorded: December 11, 12, 13, and 15, 2014, at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York

Graphic Design: Nancy Bieschke

Cover Art: Colorful Hands Frame (Pingebat/Getty Images)

© 2015 Cedille Chicago, NFP

CDR 90000 158