Store

Store

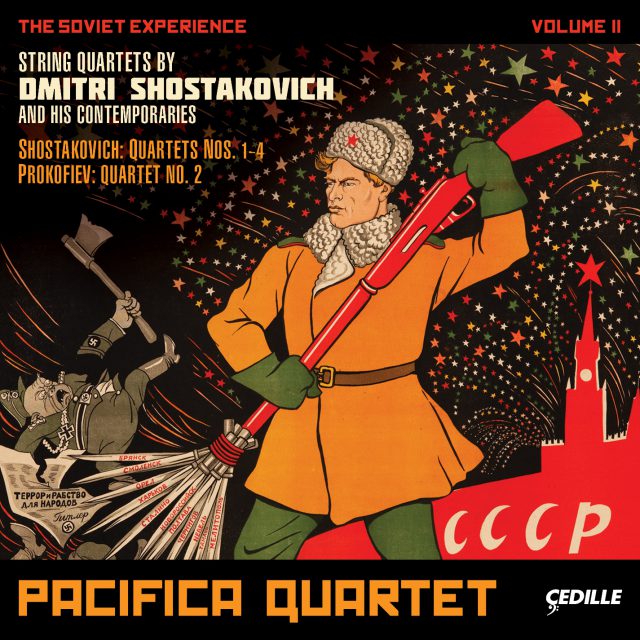

The Soviet Experience Volume II: String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries

This is the second installment in the Pacifica Quartet’s highly anticipated, four–volume CD survey of the complete Shostakovich string quartets: The Soviet Experience: String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries. The Soviet Experience is the first Shostakovich quartet cycle to include works by other important composers of the Soviet era, adding variety and perspective to the listening experience.

Volume 2 features five works from the period surrounding World War II: 1938–1949. Included are Shostakovich’s surprisingly sunny and spring–like Quartet No. 1; his often symphonic–sounding Quartet No. 2; the emotionally–powerful Third Quartet, one of Shostakovich’s greatest chamber music masterpieces; his Fourth Quartet, notable especially for its “Jewish” – themed finale; and Prokofiev’s folk–influenced Quartet No. 2.

The Soviet Experience: Volume I received universal praise on both sides of the Atlantic and was included on the best classical albums of 2011 lists of The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, The New Yorker, San Jose Mercury News, Newark Star–Ledger, and St. Louis Post–Dispatch.

The Pacifica Quartet performed the complete Shostakovich cycle to great acclaim in New York and Chicago and at the University of Illinois in Urbana, during the 2010–2011 season. The Chicago Tribune said, “The remarkable Pacifica Quartet… coaxed the music’s unfathomable sorrows, fleeting joys and macabre humor to the surface as if creating it on the spot.” The New York Times called the Pacifica “enterprising and eloquent” and said its Shostakovich installments were “beautifully and powerfully played.” In 2011–12, the Pacifica plays the Shostakovich quartet cycle in London’s Wigmore Hall.

Preview Excerpts

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975)

String Quartet No. 1 in C major, Op. 49

String Quartet No. 2 in A major, Op. 68

String Quartet No. 4 in D major, Op. 83

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev

Notes by Elizabeth Wilson

SHOSTAKOVICH

Dmitri Shostakovich came to quartet writing as a fully mature composer. When he embarked on his first quartet, he was 32 and had behind him a turbulent biography and large number of compositions, including five symphonies, three ballets, and two operas, as well as much incidental music for theatre and cinema. So his interests lay more with large dramatic forms, and also entertainment, rather than with the intimacies of chamber music. Shostakovich’s first encounter with the string quartet medium dates from November 1931, when he produced a surprise gift for the touring Vuillaume Quartet: transcriptions of two of his most popular pieces, the Polka from his ballet The Golden Age, and Katerina’s Aria (labeled simply “Adagio”) from the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. The former brilliantly and wittily exploits pizzicato (plucked) and grotesque arco (bowed) effects, while in the latter, the soaring soprano melody is successfully emulated by the first violin (although the quartet cannot match the emotional or physical power of the full orchestra in the lead up to the culmination).

Shostakovich’s first piece of serious chamber music conceived in the classical tradition was his Cello Sonata, Op. 40. Its structural parameters are worthy of Brahms, but the enormous gamut of emotions expressed, from grotesque to tragic to ironic to sentimentally lyrical, is an original and entirely characteristic feature. These and three youthful pieces — the First Piano Trio, Op. 8; Three Pieces for cello and piano, Op. 9 (not extant); and Prelude and Scherzo for string octet, Op. 11 — represented the composer’s entire chamber music output when he decided to tackle the classical string quartet form. The four years between the Cello Sonata and the First String Quartet were fraught with problems: Just after recovering from a major personal crisis involving his divorce from and remarriage to Nina Varzar, both in 1935, Shostakovich’s life was changed forever by the infamous Party editorial of January 28, 1936, in Pravda, titled “Muddle instead of Music” — a vicious attack that reputedly represented the view and voice of Stalin himself. Shostakovich was ostracized and forced at the eleventh hour to withdraw from rehearsal his yet unperformed Fourth Symphony. In trepidation, he set to work on his monumental Fifth Symphony, which was inevitably regarded as an offering to the shrine of “socialist realism.” After the triumphant first performance in November 1937, the Party authorities were ostensibly convinced of Shostakovich’s “reformation.” It was a turning point in his biography, irreversibly forcing him to turn his back on avant garde experiment and seek expression within an ideologically approved musical language. That Shostakovich was able to do so without compromising the quality of his music or limiting its all–embracing range of emotional expression, is testimony to his fierce tenacity of purpose and his unparalleled ability to innovate within the strictures of imposed boundaries.

As he approached his 32nd birthday, the time had come for a respite from public forms. Shostakovich’s desire to master the string quartet stemmed from his need for in–depth private study, reinforced by the challenge of treading on the holy ground of the great classical tradition of Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert.

The First Quartet (along with the Seventh and 11th) is one of the shortest in Shostakovich’s output for the genre. Over a mere 15 minutes, the composer compressed the classical cycle into four tautly structured movements with masterly authority. The opening Moderato is effectively a sonatina with a shortened recapitulation, where the extreme simplicity of the thematic material and transparency of the C major key emphasize the composer’s purity of expression. (In this regard, it fulfils a similar function to the opening Prelude of his great cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues for piano, Op. 87.) The second subject theme introduces a note of gentle humor, as the viola’s repeated eighth– note accompaniment and cello’s droll upward glissandi underpin the first violin’s rhetoric. The short development, based exclusively on the first subject theme, soon returns home to C major, followed by a short evocation of the second subject theme, in A–flat major, and a 12–bar codetta. This movement inhabits a world of unclouded skies, and that of a happy, untroubled childhood.

The second movement, like the first, is designated Moderato. (The quartet noticeably lacks a slow movement.) It comprises a set of variations written in a “stile russe.” The variation form almost seems an excuse for a formal exercise, similar to a task set in a conservatory class. The modal nature of the melody places it firmly in the sound–world of Russian folk song, although the theme is Shostakovich’s own, not a borrowing or quotation. In all, there are only three variations, but the device of repeating the theme in two slightly varied phrases adds substance and instrumental diversity. The theme is initially stated in the minor by solo viola, with cello accompaniment added in the second part. The first variation sounds in B–flat minor, while the second suddenly moves to a magical pianissimo E major. The cello takes over the “second half” of the theme from the first violin and soon pushes the music forward to a dramatic culmination and short transition before returning to the final pp pizzicato variation in the initial key.

The apparent simplicity and charm of the moderato movements stand in contrast with the two faster movements that follow, where the musical language is more refined and elaborate, and technical demands on the performers are considerably increased. The restless and fleeting scherzo, in the far–off key of C–sharp minor, recalls the fantastic world of Mendelssohn with its muted lightness of touch, while its F–sharp major trio, full of wistful charm, sounds in a hushed pianissimo like a distant, whirling waltz.

The last movement was actually the first one Shostakovich composed when he embarked on the quartet in May 1938. Whether or not it was the composer’s original intention to open the quartet with this cheerful and brilliant movement, it certainly makes an impressive end to the cycle. Its two contrasting themes — the first cheerfully rustic, almost like a pioneer’s march, the second cheeky and mischievous — both lend themselves to all kinds of rhythmic variation and syncopation. The composer brilliantly exploits the instrumental possibilities of the quartet and the virtuosity of the players. The music surges with uninterrupted vitality to the end with a triumphant reiteration of C major chords in the violins over the lower strings’ resonating eighth–notes. While Shostakovich’s public statements must always be taken with a grain of salt, the sunny nature of the finale appears to substantiate the composer’s claim, shortly after completing the quartet, that he was writing of “spring” and of “childhood,” for the imagery here does indeed evoke the ebullient spirit of youth.

The quartet was first performed by the Glazunov Quartet in Leningrad on October 10, 1938. The first Moscow performance, a month later, came from the Beethoven Quartet, who quickly established themselves as the leading interpreters of Shostakovich’s music: The composer entrusted the “Beethovens” with the first performance of his next 13 quartets, from the Second through the penultimate 14th.

Shostakovich wrote his Second Quartet, Op. 68, in September 1944, almost immediately after finishing his Second Piano Trio, Op. 67, a memorial to his friend Ivan Sollertinsky, who had died that February. Shostakovich was staying in Ivanovo, where the Composers’ Union had organized a retreat to allow composers access to fresh farm produce and uninterrupted creative activity, something of a luxury in the harsh conditions of WWII. The previous year in Ivanovo, he completed his monumental Eighth Symphony which, even more than its famous predecessor, evokes the tragedy and horror of war. Composed on a completely different scale than the first quartet, the second presents a large symphonic canvas in four movements that lacks the grotesque imagery usually associated with Shostakovich’s war compositions.

Despite its grand design, the quartet was composed extremely quickly. Indeed, Shostakovich confessed to his friend, the quartet’s dedicatee, composer Vissarion Shebalin, “I worry about the lightening speed with which I compose. …I compose with diabolical speed and cannot stop myself!” This speed no doubt represented the urgency with which Shostakovich wished to convey his thoughts onto paper, for the whole work is infused with a feeling of concentrated meaning; there are no unnecessary gestures or superfluous notes. Perhaps in tribute to Shebalin’s own recent “Slavyansky” quartet, the thematic material bears a predominantly Russian character, particularly in the outer movements. The overall form is that of a suite, with an opening Overture (recalling the baroque era) followed by a Recitative and Romance, a Waltz, and a Theme with Variations finale.

The first movement’s two principal themes are tautly argued, often using polyphonic imitation, reminiscent at times of the effect Stravinsky achieves in his neo–baroque Piano Sonata. The first theme, in the bright A major tonic, has two intrinsic parts; the first is a two bar motif (repeated twice) with falling intervals of a fourth and fifth, where each fundamental is ornamented with a shorter note pushing the tone a whole step upward or downward. Shostakovich marks crescendos (<) under the accompanying, short chords; these serve to emphasize the forward direction of the phrasing. In this opening, the first violin performs like a concertante soloist while the rest of the quartet acts as the supporting ripieno. In the next bars, the violin develops the theme with faster passages running up and down the scale. The second subject theme, in C–sharp minor, starts with a long note followed by a characteristic dotted eighth–note rhythm. In contrast to the first theme’s open intervals, here the melodic design emphasizes chromatiscism, with the dotted–rhythm motif featuring a falling semitone. Here again the accompaniment constantly pushes forward in crescendo, emphasizing unity rather than the difference between the two themes. The whole movement is laconically compressed and highly charged, and the general dynamic lies between forte and fortissimo throughout the exposition; relaxation (and piano) doesn’t come until the beginning of the development.

The heart of the work lives in the second movement Recitative and Romance, which opens with a dominant sixth chord in the three lower strings, an invitation to the first violin to conduct its recitative lament over their static accompaniment. The tragic intensity of the music suggests an unsung text, as the violin’s impassioned solos are punctuated by mini–chorales, or religious–sounding “Amen” cadences, from the other strings. The first part of the recitative ends on a cadential resolution, where the B–flat tonic is finally established and the Romance section begins: a heartfelt melody, evoking an aria from a cantata or passion. Following this, the first violin resumes its recitative, bringing it to a hushed conclusion before the lower strings play their final “Amen” pair of cadence chords. A particular feature of this movement is Shostakovich’s masterly ability to transfer the articulation of apparent, meaningful texts to string instruments with the utmost naturalness of expression. Here the composer is undoubtedly looking back to Beethoven — e.g., the recitatives in his A minor quartet, Op. 132, and the cello and double bass recitatives that open the finale of the Ninth Symphony.

The third movement, a fleeting and shadowy waltz in E–flat minor, constructed in rondo form, opens with a somewhat menacing theme in the cello’s low register that is taken over by an anxious, faster–moving theme from the violin. The mood of foreboding is never totally dispelled, even in the movement’s other sections, or when the material undergoes transformation.

The finale opens with a protracted introduction, reminiscent of the recitative movement, before moving on to the advertised Theme with Variations. (The enormous evolution Shostakovich underwent between writing his first and second quartets is nowhere more evident than in his treatment of variation form.) The theme’s melody is similar to the Russian lyrical protyaznaya song, whose intonational aspect, with its characteristic plagal drop of a fourth, is typical of Russian modal harmony (or lad). The theme is passed to each instrument in turn, with varying accompaniments, before undergoing other forms of development. Numerous devices are used, and the general level of intensity rises continuously, building to a furious culmination over the pedal tone of the cello’s low E–flat triplets. This section eventually subsides into a relaxed F–sharp major variation with the violins’ dancing figuration sounding over a lyrical viola and cello theme. A transitional passage on cello takes us to a D–A bass pedal, signaling the return of the theme in the tonic key, where the tranquil mood of its initial statement is finally recaptured. Shostakovich appears to be preparing us for a quiet ending, but the piece instead concludes with a forceful recall of the movement’s introduction and recitative before a final sounding of the theme in forte brings the work to its glorious conclusion.

The Second Quartet was completed on September 20, 1944. The “Beethovens” got to work immediately and gave the first performance on November 14, in the Grand Hall of Leningrad’s Philharmonia.

The Third Quartet, Op. 73 in F major, remained a personal favorite of the composer throughout his life, and is generally considered one of his greatest masterpieces in the medium. In his catalog, the work follows the Ninth Symphony, but the quartet emulates the five–movement model of the Eighth Symphony, with which it bears many similarities. Shostakovich wrote the piece between January and August 1946, when hopes for an easier life in the wake of the Soviet Union’s victory in WWII were fast receding, as he realized (perhaps ahead of his contemporaries) that Stalin would revert to even harsher forms of repression than in the late–1930s. The piece is dedicated to the members of the Beethoven Quartet.

Although never included in any published edition, the composer gave programmatic titles to the movements as follows (this was confirmed in recent years by Valentin Berlinsky, cellist of the Borodin Quartet):

- Allegretto—Calm unawareness of the future cataclysm

- Moderato con moto—Rumblings of unrest and anticipation

- Allegro non troppo—The forces of war unleashed

- Adagio—Homage to the dead

- Moderato—The eternal question – Why? And for what?

Whether Shostakovich used these titles merely as a device to shake off deeper probing by cultural ideologues, and whether they apply to WWII, to cataclysmic events through–out history, or to the Great Terror that Stalin unleashed within his own country, they still offer a useful general overview of the work’s content.

The first movement, a sonata–allegro with a polyphonic development, opens with a light–hearted, humorous first theme that seems to have stepped out of a Haydn quartet and in no way prepares the listener for the long journey and depths of tragedy to come. That he did not want the music invested with any form of satirical overtone is evident from Shostakovich’s request of performers to play this first theme “tenderly and not with intrepid dash.” [Letter to Edison Denisov, April 22, 1950] The quirky second subject is comprised of various short motifs, where a five–eighth–note phrase gets extended and developed. A concluding theme then wittily unites elements of the first and second subjects. The development starts with a brief statement of the first theme before launching into a masterly double fugue worthy of Mozart. After the recapitulation, an exuberant coda brings the movement to a brilliant and positive conclusion. This is the only movement of the quartet that exhibits a close relationship with the ebullient Ninth Symphony, rather than the profoundly tragic Eighth.

The quartet’s second movement, marked Moderato con moto, is a short, toccata–like rondo in E minor, whose three themes are differentiated, but for the most part feature ostinato (repeated pattern) accompaniments. As with the Eighth Symphony, it is one of a pair of grotesque movements that follow the first. In the opening, the viola doggedly plays heavy, repeated quarter–notes, over which the first violin winds a clumsy boorish dance, ending with a jeering upward glissando. The second theme, again heavy and grotesque, is given to the viola, accompanied by the ostinato figuration of a falling semitone in the violins. A moment of relative respite comes with the third theme, in F–sharp major, where eerie, short staccato chords sound in a frozen, distant pianissimo, perhaps reminiscent of a threatening march that has moved away. The movement ends quietly, using elements of the first theme transformed, as if drained of all energy.

In the third movement, Allegro non troppo in G–sharp minor, cruel and grotesque elements are highlighted to an even greater extent and the tension rises implacably throughout. In rondo form, it opens with an asymmetric theme (2/4 and 3/4 bars alternating), with heavy chords played against the first violin’s loutish dance macabre. A second theme, in F–minor, sees intensification of the same imagery, with the whole quartet playing multi–stopped fff chords (as many as 13 voices in all), evoking searing lashes of a whip against the first violin’s highly charged melody (perhaps a caricature of some Soviet patriotic song). A third theme stated on viola, sadistic and clumsy in the extreme, is accompanied by sarcastic pizzicato notes alternating between the cello and violins. (Here Vasily Shirinsky of the Beethoven Quartet suggested the caricatured image of a Prussian parade ground.) The whole movement is unrelenting in its menace, suggesting a protagonist trapped on all sides with no possible avenue of escape.

After the pain and cruelty so ferociously depicted in the previous two movements, the ensuing Adagio in C–sharp minor is an elegy, a space to grieve in a devastated landscape. The three lower strings proclaim, like a Greek chorus, a refrain in octaves characterized by a dotted eighth–note rhythm, a hallmark of Shostakovich’s elegiac movements (e.g., in his 11th and 15th quartets, among other works). The first violin’s lamenting quasi–recitative interrupts the principal refrain with a heartfelt melody of extraordinary beauty and intensity. The refrain theme, initially severe, soon assumes a new expressive range and is entrusted principally to the cello and first violin. As the movement draws to a close, the viola takes over the elegiac theme, sounding it over a cello bass line of repeated notes in an anapaest rhythm (short–short–long), an imitation of muted timpani at a funeral knell.

The attacca transition to the finale grows out of this moment of complete emotional devastation. The quartet’s longest and most substantial movement, this structurally highly original Moderato (a modified sonata–rondo) starts in a shadowy world. The cello states quietly in its low register a quasi–pastoral theme in 6/8. This is taken over by the first violin, which moves on to an achingly beautiful second theme, played over separated staccato notes from the other instruments. After the return of the principal theme, a new section emerges unexpectedly with a muted but playful melody in A major. This initially seems to be a dance, but it soon takes on the lamenting intonations associated with Jewish music. The finale reaches culmination when the fourth movement’s elegiac refrain explodes in canonic imitation between viola and cello — a final, heart–rending expression of grief. The cello’s solitary recitative unwinds the tension, followed by a wistful return of the dance–like theme. The piece concludes in awed and hushed tones, with the first violin’s pianissimo recitative, based on motifs from the movement’s opening, receding into the distance over a quietly sustained F major chord.

Shostakovich clearly recognized the enormous emotional impact of the Third Quartet; he always asked that it be programmed at the end of a concert. Fyodor Druzhinin, who became the Beethoven Quartet’s violist in the 1960s, left this reminiscence of the only time he saw the composer visibly moved by his own music. In preparation for a performance of the complete quartet cycle, the “Beethovens” played the Third for Shostakovich at home:

He promised to stop us when he had any remarks to make. Dmitri Dmitriyevich sat in an armchair with the score opened out. But after each movement ended he just waved us on, saying “Keep Playing!” So we performed the whole quartet. When we finished playing he sat quite still in silence, like a wounded bird, tears streaming down his face. This was the only time I saw Shostakovich so open and defenceless.

[Elizabeth Wilson, Shostakovich A Life Remembered (Faber and Faber, London, 2006) p. 502]

The Beethoven Quartet gave the first performance of Shostakovich’s Third Quartet on November 14, 1944, in the Grand Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic. The Moscow premiere followed two weeks later. As with the Eighth Symphony, the Third Quartet drew a cold reception from the Union of Composers and Soviet cultural leadership. It was seldom programmed thereafter and was on the list of Shostakovich works that were banned from performance in January 1948. Valentin Berlinsky, cellist of the Borodin Quartet, remembers how in those weeks following the Party Decree attacking “Formalism” in music (more on this below), their young quartet played this masterpiece in a Moscow Conservatory class for the composer, deliberately leaving the doors open so the magnificent music would resound around the building and act as a magnet for students to come and listen.

Shostakovich began writing the Fourth Quartet, Op. 83, in late–April 1949, and completed it on December 27. He dedicated it to the memory of Pyotr Williams, a close friend and artist with whom Shostakovich had worked in the theatre.

The years that separated this work from its predecessor were traumatic for Shostakovich and the whole country. In the aftermath of victory, new waves of Stalinist repression shook society to the core. In an attempt to impose complete ideological control over the arts, a series of campaigns were unleashed by Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin’s cultural henchman. Literature and cinema were the first to suffer, but music was soon to follow. In January 1948, the campaign against “Formalism” in music began, officially approved by Central Committee Decree on February 10. Persecution intensified in the sciences as well; the country soon was in the grip of a mass hysteria that culminated in the notorious “Doctors’ Plot” of 1952. This campaign against “rootless cosmopolitans” was a license for open anti–Semitism, something Shostakovich abhorred: his deep compassion encompassed people of all races and creeds. The renewed persecution of Jews undoubtedly influenced his choice of material in the last movements of the Fourth Quartet.

Shostakovich was not singled out for criticism in 1948 as he had been in 1936. Instead, he was condemned along with Prokofiev, Miaskovsky, and Khachaturian as a principal agent in spreading the pernicious influence of “formalist tendencies.” Shostakovich was forced to recant and make public declarations about composing tuneful music “for the people.” He was also dismissed from his teaching post at the Conservatory. Most of his music was banned from performance, and only commissions on ideologically acceptable themes were permitted. This proved a considerable blow to the composer’s finances; he was reduced to earning his living by writing music for propaganda films.

During the five–year period after 1948, when Shostakovich sat down to compose, he did so “for the desk drawer.” It was clear that public performances of his serious work would have to wait until better times. His first work “for the drawer” was the song cycle, “From Jewish Folk Poetry,” written August–October 1948, as a private reaction to the official endorsement of anti–Semitism.

Shostakovich’s next serious composition was the Fourth Quartet. He started it shortly after returning from the USA, where, much against his will, he was sent at the specific request of Stalin as a delegate to the Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace in New York in late–March 1949. The journey was an enormous strain. On return, wishing to carve some space for himself, he started work on this highly personal quartet. Shostakovich wrote it in tandem with a patriotic oratorio designed to placate the authorities: The Song of the Forests (on texts of dubious artistic merit by Evgeny Dolmatovsky). The chamber work no doubt created a welcome distraction from a task he considered repellent.

After its two predecessors’ monumental depth and scale, the Fourth Quartet seems almost lightweight. This appearance is deceptive, however, for, as often is the case with Shostakovich, the music starts as one thing and finishes as quite another. It begins with a short Allegretto movement in D major, where an open, pastoral theme from the two violins sounds over a sustained D pedal on viola and cello. When the theme is repeated fortissimo, the voices are doubled, achieving the effect of choral singing, while the lower instruments’ open D strings continue to resonate in the bass. The laconic second subject seems transitional by its very nature and leads to a further treatment of the first theme material (this short movement lacks a real sonata–form development), this time over a held E bass. After a brief return of the second theme material, the D tonic pedal is once again achieved, but the music finishes in the minor, and in hushed tones.

The second movement, Andantino in F minor, starts with the first violin’s theme, an elegiac Romance, played over a sarabande–like quarter–note, half–note accompaniment in second violin and viola, a rhythmic motif that becomes a constant feature of the movement. When the theme is passed to the cello we hear the sighing, falling semitone accompaniment of the first violin, which later assumes a separate life as an independent motif. A long upward ascent in crescendo begins, finally reaching culmination in the high register of the first violin. The movement ends with a return of the initial melody in muted pianissimo.

The Allegretto third movement starts quietly in C minor. A staccato theme in the cello’s bass register creates an eerie and enigmatic atmosphere. A second, legato theme with a characteristic dotted rhythm, played in three octaves by the cello, viola, and first violin, continues the hushed, mysterious atmosphere of the opening. Adhering to rondo form, the first theme returns before the third appears, a dance–like melody in a bright A major, played by second violin and viola against the cello’s pizzicato eighth–notes and a repetitive ricochet motif on first violin. This theme bears distinctly Jewish overtones, with flattened seventh and ninth intervals. The ensuing recapitulation of the first and third thematic episodes reverts to the initial shadowy mood before leading to a short coda based on elements of the second and first themes.

This codetta becomes a transition, leading directly to the introductory portion of the extended finale, also marked Allegretto. Here the viola’s melody line, still in C minor (the previous movement’s key) is accompanied by pizzicato notes. This passage soon compresses into an isolated motif of significance: the viola’s B–flat–G–E–flat–C, sounding in half–notes, followed by specific rhythmic patterns in the pizzicato.

Sudden loud chords announce the start of the finale in earnest, its main theme in D minor with Jewish intonations accompanied by “um–pah” pizzicatos in the lower strings. This is immediately succeeded by a second “Jewish” theme, a song–like lament. Both melodies contain the seeds for grotesque and tragic development, and are Shostakovich’s invention, rather than citations of actual Jewish folk tunes. (In this, he was following in particular Mussorgsky’s treatment of Jewish material.) The thematic material goes through various transformations before reaching a culmination at the end of the development, based on the viola motif from the introduction. In the recapitulation, the composer imbues the first Jewish theme with heightened emotional significance, as the cello plays with almost desperate intensity in its high register. After this, the tension unwinds. There follows a final, hushed reprise of the same Jewish theme, as though the musical material has exhausted itself. The piece then concludes with a short coda: Here the first violin’s rhetorical farewell is based on material from the movement’s introduction, but it is, today, also instantly recognizable as a reference to the cadenza from Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto, Op. 77 (another work written “for the drawer” during this period of heightened artistic repression). The music fades away into shadowy gloom, and over the cello’s last held D harmonic, there sounds a final, ghostly version of the introductory pizzicato motif.

Although the Fourth Quartet waited four years for its official premiere on November 13, 1953, seven months after Stalin’s death, the manuscript circulated among Moscow musicians soon after its completion. Both the Beethoven and the young Borodin quartets eagerly learned it. It appears Shostakovich preferred the Borodin’s interpretation, but he would not risk alienating the “Beethovens” by giving the premiere to the younger group: he was always loyal to his long–time performers.

The composer’s own attitude toward the Fourth Quartet in later life was somewhat ambivalent. According to composer Edison Denisov, after writing his large–scale Fifth Quartet in 1951, Shostakovich dismissed the Fourth as “mere entertainment.” This assessment is contradicted, however, by both the obvious quality of the work and the enormous courage it took for a Russian composer in 1949 to write anything that smacked of Jewish origin. For Shostakovich, it was conscience as much as artistic taste that dictated his choice.

PROKOFIEV

In August 1941, less then two months after the German invasion of Soviet Russia, Sergei Prokofiev and Mira Mendelssohn (his second wife) were evacuated from Moscow to Nalchik, capital of the Kabardino–Balkar autonomous republic in the northwest of the Caucuses. They were among a large group of artists and composers who found themselves in this normally sleepy outpost of the Soviet empire. The local director responsible for the arts, Khatu Temirkanov (father of conductor Yuri Temirkanov) was an enlightened man. To the evacuated composers, he recommended examination of a historic source of Kabardinian melodies, a collection compiled in part by composer Sergei Taneyev in 1885. (Taneyev, evidently following in the steps of his illustrious forbears, was drawn to the exotic in music; like Mily Balakiriev, he evinced a particular interest in Caucasian music.)

The Moscow composers accepted Temirkanov’s challenge. Nikolai Miaskovsky used this traditional material in his 23rd Symphony. Prokofiev interrupted work on his opera, War and Peace, to write something that would incorporate “these fresh and original melodies” in a chamber context. The composer wrote: “It seemed to me that a combination of this untouched source of oriental melodies with that most classical of all classical forms — the string quartet — could give interesting and unexpected results.” [“Khudozhnik I Vojna” (The Artist and War). Article in Sergei Prokofiev: Materials, Documents and Reminiscences ed. Shlifshteyn. Moscow 1961]

The resulting Second Quartet, Op. 92, starts out in the best of classical traditions: a brisk F major Allegro, where the character of the folk themes is refined and seamlessly assimilated into the requirements of western sonata form. The cheerful first theme, with a touch of swagger, and the second subject, with its mood of rustic humor, show the composer’s uninhibited enjoyment of melody. The mood changes in the development, where the material becomes rhythmically charged and dissonance is introduced.

The second movement, a wistful nocturne in E minor, follows a short introduction with a melancholic theme of haunting beauty, sung in the high range of the cello. A triplet scale–like figuration weaves its way around a second theme in the major before continuing as accompaniment for a last statement of the minor–key nocturne theme. In the D major middle section, the folkloric origin of the thematic material becomes more “authentically” identifiable, since it is based on a light–hearted Caucasian dance, a charming, playful Lezginka (well known as Stalin’s favorite kind of music). Prokofiev accompanies the dance theme with pizzicato and ricochet bowing effects the first section is achieved through a mirror effect, starting with the triplet figuration and G major theme, before returning to the heartfelt nocturne of the opening in the low registers of viola and cello. A final farewell sounds in the high register of the first violin against tremolando (trembling) accompaniment.

The third and final movement is a rondo of much greater dramatic substance than the other movements. After a brief rhetorical introduction, the vigorous principal theme announces itself in pointed staccato rhythm and leaping intervals. This contrasts sharply with the next section, where the violins’ theme in octaves looms ominously over the lower strings’ rumbling sixteenth–notes, tearing us away from the idyllic, pastoral world represented in the other movements and pulling us into the stark and terrible reality of war. A third theme, characterized by two contrasting features, a short legato phrase and a spiky humorous motif accompanied by pizzicati, makes a brief appearance. Interrupting the proceedings, a cello cadenza with cascading downward scales is soon elaborated by the whole quartet on a symphonic scale, bringing the work to a culmination of great tragic intensity. The music then subsides and returns to the second theme rumblings, now sounding like the distant thunder of a retreating storm. After briefly revisiting the spiky and humorous third theme, the movement concludes in a positive and sunny mood with its initial F major theme banishing all thoughts of turbulent unrest.

The Second Quartet is unusual in Prokofiev’s output as an experiment to incorporate folk music into instrumental music. (The Overture on Hebrew Themes, Op. 34, is another example, but here he was not dealing with authentic folk material.) In so doing, the composer shows an exceptional grasp of the possibilities of quartet writing, something to which he, unfortunately, never returned. This work also places him in the long tradition of Russian composers (from Glinka to Borodin and Rimsky– Korsakov) who approached folklore as something exotic and foreign, raiding it for thematic material, rather than using it, as Bartók did, as a living part of the thematic and compositional structure.

The Beethoven Quartet gave the premiere of Prokofiev’s Second Quartet in Moscow on September 5, 1942.

Cellist, author, and teacher, Elizabeth Wilson studied in Moscow under Mstislav Rostropovich. She has spent much of her professional life performing quartets and chamber music, including as a founding member (in 1995) of Xenia Ensemble, a group specializing in music by contemporary composers. She is author of Shostakovich A Life Remembered and biographies of Jacqueline du Pré and Mstislav Rostropovich (all published by Faber and Faber, London), and editor of an anthology of Shostakovich’s letters (published by Saggiatori, Milan).

Album Details

Disc 1 Total Time: (1:15:35)

Disc 2 Total Time: (53:35)

Total Album Time: (2:09:10)

Artist Name(s):

Pacifica Quartet

Producer & Engineer Judith Sherman

Assistant Engineer & Digital Editing Bill Maylone

Shostakovich Quartet No. 2 Editing James Ginsburg

Editing Assistance Jeanne Velonis

Recorded Shostakovich Quartets Nos. 1 & 2: November 18–20, 2011; Shostakovich Quartet No. 3: July 23–24, 2010; Shostakovich Quartet No. 4 & Prokofiev: August 29–31, 2011 — Foellinger Great Hall, Krannert Center, University of Illinois at Champaign–Urbana

Microphones Sonodore RCM–402 & DPA 4006–TL

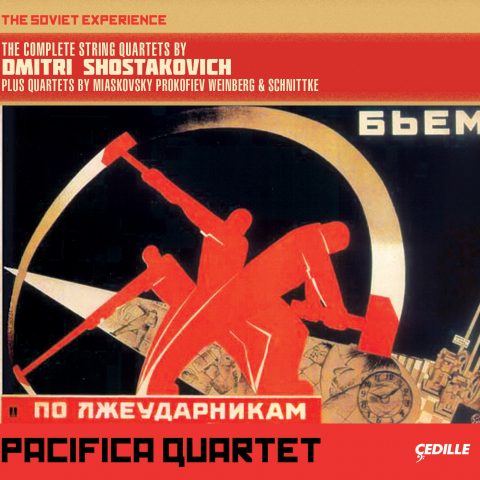

Front Cover Design Sue Cottrill

Inside Booklet & Inlay Card Nancy Bieschke

Front Cover Art The Red Army Broom Will Completely Sweep Away the Scum

From the Ne boltai! Collection — Viktor Nikolaevich Deni; October 12, 1943

At bottom left corner of image, torn order signed by Hitler with Nazi seal reads: Terror and Slavery for the People. On the bayonet–broom are the names of liberated Soviet cities, from left to right: Bryansk, Smolensk,Orylo, Kharkov, Stalino, Novorossisk, Poltava, Chernigov, Nevel, Taman, Melitopol.

© 2012 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 130