Store

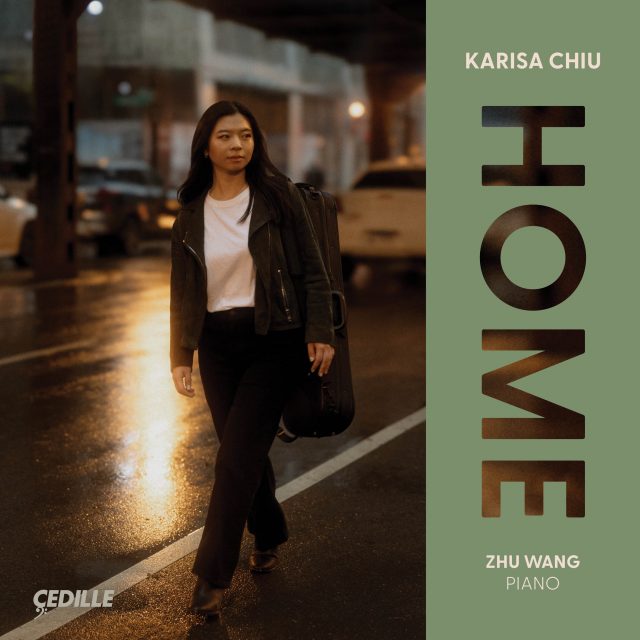

25-year-old rising American violinist Karisa Chiu, noted for her “easy virtuosity … humor, nuance… [and] playful[ness]” (Cleveland Classical), and renowned Chinese pianist Zhu Wang (“a thoughtful, sensitive performer” —New York Times) unite for Chiu’s debut album, HOME. Influenced by her Chicago upbringing, pandemic discoveries, and Korean and Chinese family roots, the recording reflects on the various interpretations of “home” in Chiu’s life, with works by Jean Sibelius, Claude Debussy, Augusta Read Thomas, Cyril Scott, and Gabriel Fauré.

A finalist in Cedille Records’ inaugural Emerging Artist Competition in 2021, Chiu earned her Bachelor’s degree from the Curtis Institute of Music and her Master’s degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music. She is currently pursuing an Artist Diploma at the Juilliard School under the tutelage of Catherine Cho and Donald Weilerstein. She is the first new solo violinist to record for Cedille in over 20 years.

Although raised in a Swedish-speaking family, Jean Sibelius chose to root his artistic identity in Finnish culture. Written between 1915 and 1918, his Five Pieces blend Finnish folk influences with the elegance of salon music, reflecting a personal and creative claim of Finland as home.

Composed in wartime exile and performed at his final public appearance, Debussy’s Violin Sonata (1916–1917) is both a farewell and a return. Intended as part of a larger French sonata cycle, the work reaches toward distant tonalities and Iberian influences, yet remains anchored in a deeply personal language — a reflection on home as something both fragile and enduring.

A lyrical, chant-inspired solo for violin, Thomas’ Incantation unfolds with patience and quiet intensity. Chiu first encountered the work years before recording it, eventually collaborating with Thomas during her time as composer-in-residence at Curtis. With Thomas’s deep ties to Chicago, the piece became a personal emblem of home — bridging Chiu’s roots in the Windy City and a new sense of belonging at Curtis.

In Kreisler’s arrangement of Cyril Scott’s dreamy Lotus Land, Chiu’s violin floats above Zhu Wang’s shimmering textures, rich with whole-tone and pentatonic color. Inspired by Tennyson’s “The Lotos-Eaters,” the piece offers a brief, sensual escape, where lyricism and stillness evoke a world apart. Discovered by Chiu during the pandemic — a strange yet meaningful chapter in her life — the work recalls a fleeting but formative anchor amid uncertainty.

Fauré’s Violin Sonata No. 1 balances classical structure with sweeping emotion and introspective calm — a work of youthful maturity. Chiu performed it during a return trip to Korea with her mother, reconnecting with family and cultural roots. The sonata evokes not only Fauré’s early voice but also a powerful emotional link to memory and belonging.

Home was produced and engineered by the Grammy-winning team of James Ginsburg and Bill Maylone, November 18–20, 2024, in the Mary Patricia Gannon Concert Hall at DePaul University (Chicago, IL).

This recording is made possible by the generous support of Patricia A. Kenney & Gregory J. O’Leary

Preview Excerpts

JEAN SIBELIUS (1865–1957)

Five Pieces, Op. 81

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918)

Violin Sonata

AUGUSTA READ THOMAS (b. 1964)

CYRIL SCOTT (1879–1970) ARR. FRITZ KREISLER (1875–1962)

GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845–1924)

Violin Sonata No. 1, Op. 13

Artists

Program Notes

View Album BookletPersonal Note

Notes by Karisa Chiu

Upon hearing the word “home,” each person will recall something different — a community, a person, a city, a culture, a memory. This album is not only a story of what home means to me, but an invitation for you to reflect on the things in your life that define home.

My journey with the violin began with my first teacher: my father. His love for music led to a singular opportunity that would change his, and therefore my, life forever: a violin-piano duo concert during his senior year of college. He performed Debussy’s Violin Sonata and Sibelius’s Five Pieces for Violin and Piano with a pianist he’d thereafter play with a thousand times more: my mother. These pieces stand out as my earliest memories of love, family, and home.

With my family’s guidance, music shifted from practice to purpose, and from that, passion. As a nervous but eager 18-year-old, I quickly found a nurturing community at the Curtis Institute of Music. There, I had the privilege to work with former Curtis composer in residence, Augusta Read Thomas. I had fallen in love with her piece, Incantation, years prior. With her strong ties to Chicago, the work came to symbolize both my home in the Windy City and my new home within the Curtis community.

Like many of us in 2020, I found myself back home when I least expected it. After the surge of independence from college, home was not the place I wanted to be, nor the place I felt I could adequately grow my violin playing. With Curtis having gone online for a full school year, there came obstacles I couldn’t fully comprehend. I was in Chicago, but it didn’t feel like home. I was alone, yet surrounded by family, with too much time and not enough to do. I desperately needed perspective, so I began to learn a new piece. I came across Cyril Scott’s Lotus Land, in an enchanting arrangement by Fritz Kreisler that now reminds me of this strange yet significant home period in my life.

My concept of home also goes back further, to my ancestral roots. My father is Chinese and my mother Korean. Elements of both cultures have intertwined to define home for me. In summer 2022, my mother and I returned to her home country for the first time in almost a decade to give a recital together. Being immersed in Korean culture and reuniting with family there as an adult, I felt oddly at home. We performed Faure’s Violin Sonata No. 1. Playing it now transports me back to that special trip to Korea.

Recording my debut album in my hometown of Chicago was a deeply personal process. Working with pianist Zhu Wang, a good friend from Curtis, and collaborating with Chicago-based Cedille Records, this album explores the many versions of home that have influenced my life and art. I hope this music offers you a sense of comfort and a reminder that “home” signifies not just a bed to sleep in or a roof over your head, but those things that are most meaningful for you.

Notes on the Program

Notes by Calvin Van Zytveld

A work of music can sustain many different, and even contradictory, private and public meanings. Karisa, both through her playing and her remarks above, invites us to hear in these five works a sense of home, intimacy, remembrance, and belonging. The purpose of these notes is to offer two additional ways to listen to and consider the works on this album. The first is through another set of private meanings — those of the composers. The second is to set aside the intentions of the composers and performers and analyze the works as objects with their own public meanings. These private and public meanings are in tension with one another but, perhaps paradoxically, also enrich each other. These works inspire performance, recording, and repeated listening precisely because of their capacity to suggest nuanced and multiple meanings.

Most of the works on this album were composed in times of crisis. Claude Debussy neared death from cancer. Jean Sibelius relapsed into patterns of heavy drinking, struggled with his finances, and watched in horror as Europe descended into the Great War. Augusta Read Thomas wrote Incantation for a friend who was dying from cancer. Gabriel Fauré was in deep despair as his love of five years had just broken off their engagement. From the morose heartbeat figure in the second movement of Fauré’s sonata to the elegiac primary theme of the outer movements of Debussy’s, one can imagine the music as expressing the inner life of their grief-stricken creators.

But to cast these works as merely musical responses to life events is to vastly underestimate the complexity of the subjectivities of their composers. It is rather doubtful that a listener, simply by hearing these works for violin, would correctly guess the tragedies that preoccupied Sibelius, Debussy, Thomas, and Fauré. Grim and gloomy material occurs only infrequently; fantasy, languor, and whimsy imbue a far greater portion. Perhaps these works reveal the hopes of their composers, occasionally punctuated by pangs of sadness, fear, or dread. And yet, if we listen to a work of a master only for autobiographical commentary, we shortchange its richness. For one thing, the composer may have intended to comment upon something other than their own life. More likely, though, is that the intentions of the composer are unknowable, and the meaning of the music principally resides in its notes, form, allusions, and performance tradition. Regarding the choice of paying heed to creator or work, D.H. Lawrence directs: “Never trust the artist. Trust the tale.” Crucially, Lawrence is not asking us to ignore the teller, only noting that the work’s content must be the final authority on its meaning.

Jean Sibelius (1865–1957)

Five Pieces, Op. 81 (1915–1918)

Sibelius came from a Swedish-speaking family in Finland. At that time, Swedish speakers were in the minority in Finland but exerted a disproportionate influence over the country’s politics and cultural life. Sibelius chose to align himself with Finnish nationalism, however, learning the Finnish language and incorporating Finnish literature and music into his works. Still, his music was written in cosmopolitan genres such as the symphony, string quartet, or the salon music heard in his Five Pieces for Violin and Piano. These five pieces warrant attentive listening for how deftly they convey the stylistic and formal expectations of the urbane genres they represent, while also incorporating flashes of Finnish folk music.

In 1915, Sibelius wrote a “Mazurka” for violin and piano that later became the first of his five pieces. The mazurka is a Polish dance composer and pianist Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849) introduced to European concert halls, salons, and drawing rooms through his imaginative works for solo piano. Sibelius’ mazurka begins with a virtuosic flourish for the violin that could be the preamble to a show piece. Instead, a lush extended chord in both violin and piano launches the two into the primary material. The first theme concludes on a modal cadence, a gesture toward the Finnish music Sibelius was studying and championing around Europe. The main theme returns briefly before we are swept up in a livelier one that features enormous leaps in range for the violin plus rapid, full-throated scales on the lowest string. These contralto interjections recall similar passages in Sibelius’ perennially popular Violin Concerto written around a decade prior.

The second piece, “Rondino,” composed in 1917, assumes the form of a rondo, a common classical structure in which one theme alternates with a rotating cast of other tunes. The theme of this short rondo bubbles over with ebullience. The repeating breathless figure in the piano together with the violin’s buoyant spiccato provide a delightful, uncomplicated statement for the contrasting materials and variations to rebel against and reflect upon. The interstitial material is more sophisticated and lends considerable pathos, but the piece, true to its salon sensibilities, ends with a wink, returning to the arch material with which the rondo began.

The third piece, “Valse,” 1917, shows the least evidence of Finnish influence. While this is, formally, a straightforward waltz, it is a particularly beautiful one.

The fourth piece, “Aubade,” written in 1918, begins deceptively. Disjunct chords shared by violin and piano plot an unusual course into unexpected harmonies. The mystery of these chords is soon undercut by charming lyricism, however. The etymology of the piece’s title captures an element of this unlikely juxtaposition. Aubade (derived from “aube” or dawn) first denoted music to be played in the morning, but it also came to be used to describe certain military band pieces that were performed to honor rulers.

The final piece, “Menuetto,” also 1918, has a striking trajectory. The minuet is a dance form with roots in the social dances of the French aristocracy. The modest aim of this particular minuet might be guessed by Sibelius’ use of the diminutive, “Menuetto.” In the first section, the violin plays delicate trills while the piano quietly articulates spare, minor harmonies. The effect is elegantly pastoral, yet cold — like a lone bird singing in a frozen Finnish forest. This pastoral evocation is overcome by severe and spirited dancing material, paying clear homage to the regal origins of the dance form. The minuet alternates between these two cold spaces until the contrasting middle section, in which the cold is dispelled by a folksy modal melody resembling a lullaby. The warmth persists for a moment after the return of the primary themes, now heard in major before the piece finally slinks back into minor.

Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

Violin Sonata (1916–1917)

Debussy’s Sonata for Violin and Piano is relatively short and contains only three movements. It is the third and final piece in a would-be set of six sonatas Debussy had agreed to write. While illness and death prevented the composer from realizing the others, he did manage to play the piano part of this sonata — his final public performance.

The first movement begins with nebulous materials whose meter and tonality can only be guessed at on first listening. Gone are the sure-footed, stylized dance rhythms of Sibelius’ Five Pieces, as Debussy’s Sonata darts ceaselessly from one rhythmic feel to another. These two works do share certain harmonic sensibilities, however. Both draw upon modal harmonies liberally, and both prominently feature the Phrygian cadence (inverted cadence ending on the dominant). In Sibelius’ Mazurka, this cadence alludes to the folk music of Finland, while Debussy’s Phrygian cadence pays homage to the Iberian music he had long admired.

Debussy’s second movement delivers a scherzo-like romp through numerous keys as spritely staccato passages deposit us in episodes of enigmatic lyricism. The last note — a coquettish short chord in the piano — seems to retract any and all of the preceding severity of tone.

The third movement begins with the primary theme of the first movement, but not presented triumphantly, as Beethoven was wont to craft his heroic, cross-movement cyclical developments. Rather, Debussy recalls this melody with the violin only in passing, amid restless and unstable accompaniment in the piano — like the recollection of a distant memory whose meaning cannot be parsed. Sweeping pentatonic gestures immediately dispel this pensive contemplation, however. Although the movement is short, it is voluble and varied, exploring remote keys and textures, resting nowhere as it rushes onward with a vitality unbounded by classical forms.

Augusta Read Thomas (b. 1964)

Incantation (1995)

The word “incantation” comes from the Latin incantatio, meaning “art of enchanting.” The Latin word can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European root “kann,” which means to sing or chant. Although incantations are often associated with funerial practices, Thomas wrote this one for violinist Catherine Tait, who performed it just weeks before succumbing to terminal cancer.

This incantation for the living begins questioningly, like a voice chanting, unfolding us into the lyrical piece, with single notes leading to the first moment of vertical harmony: a minor sixth followed by another, a half step lower. The pace is neither hurried nor glacial, but rather contemplative and patient.

Thomas’s website states that this work, “celebrates Catherine’s generosity of spirit. The music sings out, with beauty and grace, always with a richness and elegance. The work falls loosely into an ABA form, ending as it were, on a question, with a major seventh hanging in the air, unresolved.” Although Debussy wrote his Violin Sonata with death at his doorstep and Thomas wrote Incantation near the start of a long and successful (ongoing) career, it is this latter work that feels darker and more haunting.

Cyril Scott (1879–1970) arr. Fritz Kreisler (1875–1962)

Lotus Land (1905, arr. 1922)

Musical impressionism is most often associated with French composers, but English composers such as Frederick Delius and Cyril Scott also participated in the aesthetic. When Scott wrote Lotus Land, lotuses represented more than a plant with beautiful flowers and an edible, crunchy root. Lotuses were associated with a hazy set of ideas: China, East Asia, relaxation, and dreaming. The figure of the “lotus-eater” originates from Homer’s Odyssey, where Odysseus encounters a people who, after eating the lotus plant, forget their home and neglect their duties, losing themselves in placid reverie. This Homeric episode commanded particular attention following the publication of Tennyson’s “The Lotos-Eaters” in 1832. Through Tennyson, the lotus came to symbolize an escape from modernity and its dread:

Eating the Lotos day by day,

To watch the crisping ripples on the beach,

And tender curving lines of creamy spray;

To lend our hearts and spirits wholly

To the influence of mild-minded melancholy…

Let us swear an oath, and keep it with an equal mind,

In the hollow Lotos-land to live and lie reclined.

Fritz Kreisler, who arranged Scott’s Lotus Land for violin and piano, was the perfect avatar for the sophisticated indolence romanticized by Tennyson. A celebrity violin virtuoso and composer, he mostly avoided practicing violin or writing music in weighty genres such as the opera, symphony, or string quartet. This was not for lack of training or prowess: he studied counterpoint with none other than Anton Bruckner. Writing ambitious pieces or practicing his violin would have been unbecoming for the suave Kreisler, who cultivated a genteel air of detachment and indifference. In this arrangement of Lotus Land, cozy extended harmonies gently bump into exoticist whole tone and pentatonic scales in the piano, while the violin dances nimbly, high above.

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924)

Violin Sonata No. 1 Op. 13 (1875–1876)

In contrast to Debussy’s Sonata, which is a sonata only in the broadest sense, this romantic sonata hews diligently to classical formulas. The rigorous structure does not come at the expense of inventiveness or expressivity, however; the work is one of the most striking in the repertoire and represents one of the composer’s first mature works.

The first movement demonstrates most apparently the influence of Robert Schumann on the young composer. Plaintive bursts of tremendous pathos melt into quiet melancholic introspection before erupting into effusive declamations. As with many Schumann works, Fauré navigates dramatic shifts in affect deftly and without marked interruptions.

The second movement begins with a heartbeat figure in the lower register of the piano: in bars of 3/4 time, two ominous pulses occupy the first two of the three beats. When this same rhythmic pattern returns midway through the movement, however, it is in major with different pitches assigned to each note, creating the effect of a waltz: grief transformed into dancing. While the opening melody returns later in the movement, it is no longer accompanied by the existential heartbeat motif. The turn toward joy proves to be lasting, with the following two movements alternating between exuberance, exquisite lyricism, and gentle repose.

Calvin Van Zytveld is a composer and cellist currently pursuing a PhD in Musicology at Stanford University.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Recorded

November 18–20, 2024, Mary Patricia Gannon Concert Hall, DePaul University (Chicago, IL)

Publishers

Incantation © 1995 Augusta Read Thomas

Cover Photo Jaclyn Simpson

Graphic Design Bark Design

CDR 90000 239