Store

Store

French Impressions: Chamber Music by Chausson & Tailleferre

Acclaimed concert violinist Rachel Barton Pine, sought-after pianist Orion Weiss, and the multiple Grammy Award-winning Pacifica Quartet join forces for their new album French Impressions: Chamber Music by Chausson & Tailleferre, celebrating captivating works by French composers Ernest Chausson and Germaine Tailleferre, whose chamber music deserves greater attention on recordings.

Chausson’s Op. 21 sextet, titled Concert, known for its unusual orchestration of solo violin, string quartet, and piano, takes advantage of the quasi-orchestral capabilities of a chamber ensemble. The only work on the album featuring Rachel Barton Pine, Pacifica Quartet, and Orion Weiss as a collective, Concert is regarded as one of the most important French chamber music works of the late-19th-century fin-de-siècle era.

Germaine Tailleferre was a prolific composer and the only female member of the group of celebrated 20th-century French composers known as Les Six. Tailleferre was a piano prodigy who enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire at age 12, defying her father’s objections. Her compositions span symphonic, chamber, and film music. A winner of numerous premier prix, she studied with revered composers including Maurice Ravel, whose work significantly influenced her versatile style.

Violinist Rachel Barton Pine showcases her “astonishing and joyful” (Washington Post) artistry, alongside the “powerful technique and exceptional insight” (Washington Post) of pianist Orion Weiss for Tailleferre’s Violin Sonata No. 2, Pastorale, and Berceuse for Violin and Piano — works that often express a nostalgic longing for home and display dynamic and adventurous interplay between the violin and piano.

The Pacifica Quartet, known for its “remarkable expressive range and tonal beauty” (New York Times), is featured on Tailleferre’s String Quartet, a piece acclaimed for its playful themes, fluid accompanimental figuration, and bold harmonies.

French Impressions: Chamber Music by Chausson & Tailleferre was produced and engineered by the Grammy-winning team of James Ginsburg and Bill Maylone. The album was recorded on January 5-6, 2025 at Mary Patricia Gannon Concert Hall, DePaul University (Chicago, IL) and February 3, 2025 at Sasha and Eugene Jarvis Opera Hall, DePaul University (Chicago, IL).

Preview Excerpts

ERNEST CHAUSSON (1855–1899)

Concert for Violin, Piano, and String Quartet, Op. 21

GERMAINE TAILLEFERRE (1892–1983)

Violin Sonata No. 2

TAILLEFERRE

TAILLEFERRE

String Quartet

TAILLEFERRE

Artists

1: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss, Pacifica Quartet

2: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss, Pacifica Quartet

3: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss, Pacifica Quartet

4: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss, Pacifica Quartet

5: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss

6: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss

7: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss

8: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss

9: Pacifica Quartet

10: Pacifica Quartet

11: Pacifica Quartet

12: Rachel Barton Pine, Orion Weiss

Program Notes

View Album BookletProgram Notes

Notes by Elinor Olin

In 1900, Franҫois-Auguste Gevaert, esteemed scholar and director of the Brussels Conservatory, told his students that Paris was unlike any other musical capital in Europe. In addition to “four of the best symphony orchestras in the world” and influential private salons, there were public concert series presenting large- and small-scale musical works: “the Société Nationale de Musique, the Groupe Jeune France, not to mention the Ballets Russes and the Concerts Wiéner, the majority of these manifesting the authentic history of music in our times.” Collectively, these concert organizations had a tremendous impact on French composers of the era that came to be known as the fin-de-siècle —especially on their chamber music. Both composers represented on this recording were active contributors to these performance organizations, and as such, participated in transformational musical developments and trends. This album gives us not only beautiful chamber music, exquisitely performed, but also a more complete picture of the kaleidoscopic musical world of Troisième Republique France and beyond.

Amédée-Ernest Chausson (1855–1899) was the personification of the French fin-de-siècle. In both life and works, he represented the summation of one era and the dawn of another. He was an ardent champion of French music and painting and an early champion (and financial supporter) of Claude Debussy, but also influenced by the music of Richard Wagner.

Born into an affluent family, Chausson was educated privately. At age 16, his tutor introduced him to influential Parisian salons where he met artists Henri Fantin-Latour and Odilon Redon, and musicians including composer Vincent d’Indy. After briefly studying with Jules Massenet and César Franck at the Paris Conservatoire, Chausson undertook several “pilgrimages” to hear Wagner’s music in Munich and Bayreuth (including to hear Parsifal on his honeymoon in 1883). (He later disavowed this musical infatuation, writing to a friend that “de-Wagnerization” was necessary in order to embrace more clarity and a “healthier” outlook.) In his own Parisian salon, Chausson entertained renowned poets, artists, and musicians, such as Albéniz, Cortot, Debussy, and Ysaÿe. A prominent member of the Société Nationale de Musique, founded with the Latin motto Ars Gallica (French Art) in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War, Chausson was an influential voice in independent musical circles of early-Third Republic France.

Chausson’s tragic death in a bicycling accident cut short a compositional career that hadn’t begun until he was nearly 30, with his first publication — a song collection — in 1884. While best known for his Poème for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 25 (1896), Chausson composed in many genres including operas, sacred music, symphonic poems, and songs. His contemporaries held his chamber music in the highest regard, however. His friend, French music critic Georges Jean-Aubry, wrote in homage that Chausson’s inherent personality came through in the “exchange of confidences [that] led him to seek out in narrower limits, all the qualities that could be drawn from individual instruments.” Highlighting Chausson’s Concert for Violin, Piano, and String Quartet, Op. 21 as one of the most important French chamber music works of the late-19th century, another contemporary writer described the work as “an enchantment without malice,” citing its reflection of the composer’s very being.

Dedicated to virtuoso violinist and composer Eugène Ysaÿe and premiered by Ysaÿe (violin), Auguste Pierret (piano), and the Quatuor Crickboom in 1892. Chausson’s Concert is an extraordinary piece, exploring and expanding the boundaries of chamber music genres. The work is scored for the unusual combination of solo violin, string quartet, and piano, alternately presenting the intimate sounds of a solo piano work or a violin sonata alongside the grand style of a violin concerto, utilizing the quasi-orchestral potential of the string quartet. The title, Concert, is also unusual and may reflect Chausson’s admiration for 18th-century French composers such as Jean-Philippe Rameau, who designated chamber works featuring keyboard and strings with the same title. Chausson’s performance indications in the work — Décidé (decisive), Calme, Librement (freely), Très animé (very lively) — are intentionally French (instead of Italian), perhaps a manifestation of his Ars Gallica stance.

The untitled first movement begins with a bold, fortissimo statement by the solo piano introducing the movement’s foundational motive. The string quartet echoes this three-note figure several times while the piano plays cascading arpeggios elaborating on the original motive. When the solo violin enters, it is in equal textural partnership with the piano, as the music fluidly shifts in character to take on another of its multiple genre personas. The movement reaches a high point as the piano offers virtuosic figurations while the string quartet plays in counterpoint with the soaring solo violin. The final section reintroduces the main motive in its original form, accompanied by the cascading arpeggios, now in both string quartet and piano, as the solo violin reaches stratospheric heights, fading away with a sustained pianissimo murmur.

The Sicilienne second movement opens with characteristic, lilting rhythms in the solo violin, accompanied by familiar-sounding arpeggiation from string quartet and piano. The violin’s Sicilienne melody is taken up successively by the piano and individual members of the string quartet. Ultimately, all of the strings play in unison as the piano’s cascading accompaniment leads into an ascending gesture from the violin that suggests an offering to the heavens.

The third movement has no title, just the performance indication Grave. An ominous chromatic ostinato in the piano establishes the emotional context of, as one contemporary wrote, “the most profound sadness” of a solemn ritual “celebrated in the crypt of the heart.” The basis of all the melodic material in the movement, the piano ostinato is first augmented by a slower version of the melody in the solo violin, establishing the duo instrumentation that predominates throughout. The string quartet takes a more active role at the movement’s climax, partnering with the increasingly virtuosic piano to create an almost-orchestral sound. The strings all come together playing in unison texture as the piano restates the opening chromatic ostinato to bring the movement to a solemn close.

The Finale, marked Très animé, provides a dramatic shift of mood, opening with lively, syncopated rhythms introduced by the piano then taken up by the ensemble in octaves. As with the first movement, the opening material here is varied by each of the instruments throughout the remainder of the piece. This last movement fully explores the sound genres alluded to in the previous movements, from the intimacy of a piano interlude or a piano-plus-violin duet, to the grandeur of a piano concerto, and the full utilization of each instrument in the piano-and-strings sextet. The result is often spectacular — in the French sense of the word, derived from spectacle or staged event. The piano has the last word, with a Gallic flourish that seems to say, with a wry smile, “it’s nothing; let’s do this all again!”

Marcelle-Germaine Tailleferre (1892–1983) is perhaps the most famous composer who (almost) no one knows anything about. Music students memorize her name as the only female member of the early-20th-century group of French composers dubbed Les Six, but most would be hard-pressed to cite any of her compositions or achievements. Tailleferre was, in fact, a prolific composer of symphonic, chamber, stage, and film music who participated actively in French and international musical life for more than six decades.

Musicologist Henri Collet coined the moniker, “Les Six,” as a journalistic convenience in January 1920. His article for the literary paper, Comoedia, “Les cinq russes, les six français et Erik Satie,” referenced the late-19th-century Russian “Mighty Five,” whose works established a true Russian style, and promoted the alliance of six young French composers: Francis Poulenc, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Georges Auric, Louis Durey, and Germaine Tailleferre. Collet’s tribute highlighted what would be the only collaboration among the group, their Album des Six (1920), calling the collection of piano morceaux “a magnificent return to simplicity, a renovation of French music.” The publicity value of membership in this collective did no harm to the young composers’ careers, although there was no real shared aesthetic beyond a rejection of (in the words of Jean Cocteau) “a heavy fog pierced with flashes of lightning from Bayreuth which became a light snow tinted with Impressionist sunlight” — a not-subtle disparagement of both Wagner and Debussy.

Germaine Tailleferre was a prodigy, both as a pianist and composer. As a young girl, she played her own transcriptions of Stravinsky ballets at the piano in salon gatherings. She enrolled in the Paris Conservatoire at age 12 — against her father’s adamant objections. In common with many at the time, he believed a woman pursuing a professional career as a performer might as well be working in a brothel. Paying her own fees at the Conservatoire, Tailleferre won more premiers prix — in Counterpoint, Harmony, and Accompaniment — than any of the other Six. She grew disenchanted with the institution’s reactionary culture (she once was expelled from her organ class for improvising in the style of Stravinsky!) and subsequently studied composition with Charles Koechlin and befriended Maurice Ravel, who coached her on orchestration.

After receiving a commission in 1923 from the influential Princesse de Polignac, Tailleferre wrote and performed her Piano Concerto for the Concerts Jean Wiéner. A reviewer in the conservative weekly, Le Ménestrel was not impressed, however: “Mlle Tailleferre belongs to the ‘Group of Six;’ which is to say that for her both consonance and harmony are treated as young people today treat their parents: without respect.” Undeterred, Tailleferre (whose surname roughly translates as “crafted from iron”) preferred to cultivate what a different reviewer called the “delightful vagabond spirit particular to [her] art.” During World War II, she left occupied France and travelled to the U.S. for an extended period, but composed no music until she returned home in 1946. While in the States, however, Tailleferre wrote an article for the journal Modern Music about the difficulties facing French musicians, including the appalling treatment of her Jewish colleagues. Her long career allowed her to explore many genres: numerous ballets and operas, and more than 30 film scores (including a documentary film she scored when she was nearly 80). Her chamber music ranges from solo pieces for piano or harp (which she also played) to small ensemble music for nearly every wind and string instrument configuration, including a wind quintet written (in her mid-late 80’s) in 1979. At age 77, she accepted a part-time position as a rehearsal pianist for children’s dance classes near her home in Paris — a post she held until shortly before her death at age 91.

Tailleferre wrote her Second Sonata for Violin and Piano in 1947 (publ. 1951), after her return to France post-WWII. A revision of the Violin Concerto (1936) she wrote for French virtuoso Yvonne Astruc, it exhibits the “vagabond spirit” ascribed to her early in her career. Although it sounds deceptively simple, Tailleferre’s Sonata is, in reality, quite technically demanding. The first movement, marked Allegro non troppo, is a lively plein air romp for the violin with a more turbulent middle section. After a recap of the opening melody, it ends with an ascending pianissimo sigh. The brief second movement, Adagietto, is a ballade for the violin in harmonically adventurous partnership with the piano. The energetic Final resonates with the neo-classical spirit of Poulenc, who also wrote (or re-wrote) his sonatas for violin, cello, and various woodwinds during the late-1940s. After venturing through a series of harmonic adventures, the sonata ends with violin and piano joining forces in a brilliant virtuosic flourish.

Tailleferre wrote her Pastorale for Violin and Piano in Grasse during 1942, just before she left war-torn Europe for the United States. Its gentle sicilienne rhythms and tranquil melody conjure the floral scents of the Côte d’Azur and suggest a nostalgic yearning for a better time.

Tailleferre dedicated her String Quartet (1919) to Arthur Rubinstein, who had been introduced to Parisian musical circles by the Princesse de Polignac in the early years of the 20th century. Significantly, the String Quartet received its premiere in January 1920, at a concert of the prestigious Société Nationale de Musique just weeks before Henri Collet penned his promotion of “Les Six.” Collet singled out Tailleferre’s Quartet as one of the group’s best works, saying he knew of none that were more well-composed. The first movement begins with a principal theme handed off among the instruments in what Collet characterized as a mischievous game of hide and seek. The harmonies become increasingly bolder, incorporating double stops to create a dissonant sort of chord planing — taking Debussy’s technique one step further. The Intermède begins without pause between movements; its playful melody is introduced in rhythmic unison. A middle section features fluid accompanimental figurations supporting gentle syncopations that are gradually retransformed into the opening theme. The Final begins as a modally inflected jig that is more rhythmic than melodic. The mood shifts in the second section with an octatonic melody in the viola, supported by insistent rhythms that soon transform into atmospheric arpeggios below the violin’s contemplative melody. The jig-like melody is reintroduced and is then deconstructed until the movement ends, slowing and diminishing into an open, sustained pianissimo sonority.

Berceuse for Violin and Piano, written in 1913 and published 11 years later, was affectionately dedicated to “mon Maître et Ami Monsieur H. Dallier,” who had been the composer’s Harmony professor at the Paris Conservatoire. The piano’s rocking accompaniment in this charming lullaby gently supports a continuously developing violin melody, incorporating a soupҫon of harmonic dissonance as it explores the full range of the violin. This early musical gem both foreshadows and encapsulates the spontaneity, succinct expression, and Gallic refinement of Tailleferre’s distinctive musical style.

© ELINOR OLIN 2025

Dr. Elinor Olin is a professor at Northern Illinois University School of Music and has a background in both music performance and music history.

A Personal Note

Notes by Rachel Barton Pine

This recording is the realization of a three-decades-old dream.

From age 10 to 17, I had the great fortune of studying with the incomparable Almita and Roland Vamos. I grew up with their son, Brandon, and their student (and future daughter-in-law) Simin, founding members of the Pacifica Quartet. The first time I heard this newly formed group in the mid-90’s, I instantly became a fan and dreamed of one day performing the Chausson Concert with them.

The Chausson is special for violinists like me, who love to play chamber music and love string quartet repertoire but are not a member of a quartet. We frequently perform at chamber music festivals, joining ad-hoc groups to rehearse and perform string trios, piano trios, string sextets, and more. However, the string quartet is a specialized genre that is generally left to formed ensembles that have worked together for years. Quartets often add a viola or cello to perform viola or cello quintets, but there is virtually no repertoire for string quartet with an added violin.

Thank goodness for the Chausson Concert for violin, piano, and string quartet!

It’s thrilling to have finally had the opportunity to collaborate on the Chausson with the Pacifica. Our close friendship and shared musical roots made playing together feel natural, as we easily matched character ideas and tone colors.

I feel honored that we were joined by Orion Weiss, another long-time friend whose playing and artistry I greatly admire. I first met and collaborated with him nearly two decades ago at a festival in Montreal, where I was struck by his exceptional blend of technical mastery, artistic vision, and collaborative sensitivity.

Another wonderful connection that helped bring this project to fruition is that we all share the same manager, John Zion — making this an all-MKI Artists project!

When I was considering options for repertoire to round out the album, John suggested Germaine Tailleferre. I knew of her but wasn’t very familiar with her music. Listening to her compositions, I was struck by their beautiful quality of sounding simultaneously very familiar, yet unexpected. Each work we chose grabbed me immediately and continues to grow on me the more time I spend with it.

It’s a great pleasure to share this album with you. I hope you enjoy listening to it as much as we enjoyed creating it.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Recorded January 5–6, 2025, Mary Patricia Gannon Concert Hall, DePaul University (Chicago, IL); February 3, 2025, Sasha and Eugene Jarvis Opera Hall, DePaul University

Rachel Barton Pine’s Violin Guarneri “del Gesù,” Cremona, 1742, the ‘ex-Bazzini, ex-Soldat’

Bow Isaac Salchow, copy of Dominique Pecatte

Strings Vision Titanium Solo by Thomastik-Infeld

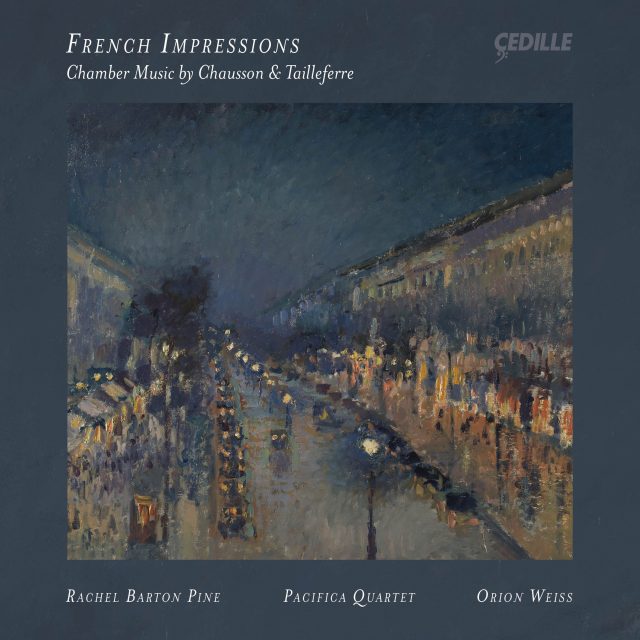

Cover © Camille Pissarro: The Boulevard Montmartre at Night (1897). Used

with permission from The National Gallery, London

Publishers

TAILLEFERRE: Violin Sonata No. 2

© 1951 Editions Durand

TAILLEFERRE: Pastorale

© 1946 Elkan-Vogel

Graphic Design Bark Design

CDR 90000 238