Store

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918), younger sister of the more famous Nadia Boulanger, was a brilliant and precocious French composer who dazzled the world of European music at the beginning of the 20th century. At age 19, Lili Boulanger became the first woman to win France’s Prix de Rome. In her short career, Boulanger advanced the impressionism of her era, finding her own voice in music that’s expressive and luminous, moving and enchanting. Debussy descriptively described her music as “undulating with grace.”

To place Boulanger’s music in context, the CD offers songs by prominent French composers who had a connection to her music: Fauré, Ravel, Debussy, Messiaen, and Honegger.

Clairières dans le ciel, Boulanger’s 1914 cycle of 13 songs based on poems by Francis Jammes, shows her talent for bringing poetry to life: Through sophisticated harmonic language, mood-evoking chromatics, and her careful choice and use of keys, her music reflects and enhances her chosen texts. Ms. Michaels describes Clairières as “a major work in the vocal literature, comparable to the other cycles everyone knows. In this genre, I would rank her with Schubert.” Ms. Michaels says that preparing the piece was “a huge undertaking” because of its length, technical demands on the singer, ensemble challenges, and extremes of dynamic range and pitch. Ms. Michaels and pianist Rebecca Rollins rehearsed and performed the cycle for two years before recording it. “The music always more than repaid our efforts,” Ms. Michaels says.

Boulanger’s four other songs on the recording represent slightly different periods in her seven-year career. Reflets (Reflections) is from 1911 and bears some affinity to Fauré. In Attente (Expectation) and Le retour (The Return), both from 1912, her harmonic language is already more complex and chromatic, enhancing her warm, lyric writing. In contrast, Dans l’immense tristesse (In an Infinite Sadness, 1916), in B-flat minor, conveys the anguish of the lyrics through dark sonorities and dissonant harmonies.

Fauré, represented by three songs on the CD, was a Boulanger family friend and an important influence on Lili Boulanger. She never met Debussy, but they knew each other’s music (as evidenced by Debussy’s glowing comment.) Ravel met Lili Boulanger in Fauré’s classes at the Paris Conservatoire, and his aesthetic can be heard in her skillful, colorful writing for piano, as well as for orchestra. Honegger and Messiaen postdate Boulanger in their musical output, but they had meaningful connections to her, and their music suggests possible directions hers might have taken, had she lived longer.

Preview Excerpts

GABRIEL FAURE (1845-1924)

LILI BOULANGER (1893-1918)

MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937)

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918)

LILI BOULANGER

Clairieres dans le ciel

OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908-1992)

ARTHUR HONEGGER (1892-1955)

LILI BOULANGER

Artists

Program Notes

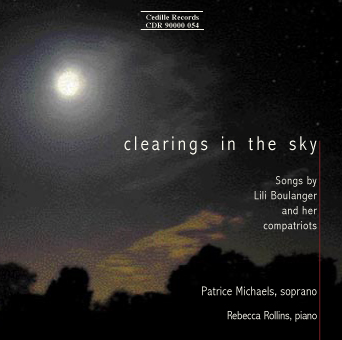

Download Album BookletClearings in the Sky

Notes by Rebecca Rollins

Lili Boulanger lived only twenty-four years (1893-1918), was ill most of her life, and created musical works of great beauty and sophistication, works that Debussy described as “undulating with grace.” How did this happen? How did this woman manage to become so creative and productive in spite of her difficult and short life?

Lili Boulanger was French, and France had a recognized and lengthy tradition of women in music and the arts. This history ranged from medieval women troubadours to the professional women musicians and composers of the Baroque era (Elisabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre being the most prominent) to the numerous women salon leaders of the 19th century. France’s openness and acceptance toward women in the arts and professions was unique among European countries.

Lili Boulanger was born on August 21, 1893 into a prominent, well-connected Parisian family with a long history of impressive musical and theatrical accomplishments. The Boulanger grandparents had won music competitions at young ages. Lili’s father, Ernest, won the Prix de Rome competition in composition in 1835, when he was nineteen. Lili’s mother, Raïssa (1858-1935), met Ernest when she became his voice student at the Paris Conservatoire. They “married” in 1877, when he was sixty-two and she was nineteen. (According to Boulanger biographer Léonie Rosenstiel, the couple may not have been legally married.) Nadia Boulanger, who would become one of the great composition pedagogues of the twentieth century, was born in 1887. Lili arrived six years later, when her father was seventyseven. The family environment was a stimulating one, and accomplishment at an early age was expected. Family friends included Gounod, Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Dupré, and many other prominent French musicians.

From an early age, Lili showed every indication of following in and contributing to the Boulanger tradition of musical accomplishment. She sang melodies by ear at age two. At five, Lili began attending classes with Nadia at the Conservatoire. Her earliest musical studies included violin, cello, harp, piano, and harmony. By 1901, at the age of eight, she was auditing classes in organ, composition, and history. Her studies were sporadic, however; a severe case of bronchial pneumonia at age two left her with a weakened immune system and ill health for the rest of her life. (She eventually died from an intestinal disease.) The specter of death affected Lili from an early age. Her father, for whom she was a favorite, died suddenly when she was six. He was eighty-four, but it came as a great shock to Lili. She found comfort in her strong Catholic beliefs and in her musical pursuits. Lili’s first composition (which she later destroyed), from 1906, was a song about death and grief, themes that permeate her surviving works. Despite her early encounters with sickness and death, Lili was a cheerful and charismatic child with an insatiable curiosity who pursued her studies with a fierce ambition.

When Lili was sixteen, she decided she would be a clearings in the sky notes by Rebecca Rollins — 4 — composer. Winning the Prix de Rome — the competition her father won in 1835, and in which her sister placed second in 1908 — became her immediate goal. Her perseverance was astounding as she set an intensive course of study for herself over the next three years, simultaneously studying harmony, fugue, counterpoint, and composition. In 1912, she was officially admitted to the Conservatoire by Fauré, made her debut as a composer, and attempted the Prix de Rome. The competition was a grueling affair that involved, among other things, being sequestered for one month while writing a cantata for soloists and orchestra on a specified text. Lili’s illness forced her to withdraw in 1912, but the following year she tried again. Although she still was not well, her fortitude prevailed and she emerged triumphant. Lili’s winning cantata, Faust et Hélène, created a sensation and received enthusiastic reviews from everyone — the judges, the public, the press, and her colleagues, including Debussy.

This was an amazing feat: Lili Boulanger had captured First Grand Prize in the Prix de Rome at the age of nineteen — the first woman ever to do so — and she had won decisively. She became an international celebrity almost overnight. The resulting whirlwind of appearances and performances sapped her limited strength, however, and she had to curtail her activities. Her two-year residency at the Villa Medici in Rome (part of the Prix de Rome prize) was interrupted frequently due to illness and also the onset of World War I. Nadia and Lili organized a war relief effort for musicians and friends, providing moral support and enabling correspondence among colleagues. Lili continued composing and readying scores for publication when she was able, but her health was rapidly deteriorating. She remained courageous and determined, but frequently expressed frustration with her weakness.

From 1916, Lili was ill more often than she was well, but she continued to work. She knew she had limited time and that she had to work quickly when she was able. Her strength of character, the support of her mother, sister, and many devoted friends, and her own incredible abilities carried her through much pain and suffering. Her last piece, Pie Jesu, a haunting setting for voice, string quartet, harp, and organ, was dictated from her death-bed to Nadia. Lili Boulanger died on March 15, 1918, never having heard most of her music performed. Her sister, Nadia, lived until 1979 and was an ardent, life-long promoter of Lili’s work.

As a composer, Lili Boulanger quickly absorbed everything she was taught and moved forward to forge her own style. The French tradition she inherited from Fauré and others inspired her predilection for setting texts; almost all of her music is vocal. In her harmonic language and instrumentation, she remained close to the composers around her, especially Debussy. But she was also an experimenter, bending forms, stretching harmonies, and incorporating new ideas. Elements in her music foreshadow the later music of Ravel, Honegger, and even Messiaen.

Clairières dans le ciel (Clearings in the Sky), a major work in Lili Boulanger’s ouevre, was written in 1914, before and during her stay at the Villa Medici in Rome. The initial idea came from Lili’s close friend, Miki Piré, who gave Lili a collection of poems by Francis Jammes. Lili completed the cycle at — 5 — Miki’s home in Nice, and sang a private “premiere” for her in May of 1917, with Nadia as pianist. The official premiere came in March of 1918, one week before Lili’s death; she was too weak to attend. Eleven of the songs bear dedications to special people in Lili’s life, including Fauré (No. 1); Miki (No. 2); Lili’s mother (No. 4); and David Devries, the tenor who sang the premiere of Lili’s cantata Faust et Helène (No. 11).

The interweaving of music and poetry in Clairières provides a wonderful metaphor for Lili’s life. Her determination and optimism fueled a creative vision that constantly sought to turn tragedy into triumph. This attitude was manifest at the very beginning of her work on the cycle, when Lili asked Francis Jammes for permission to change the title from his Tristesses (Sorrows) to the more hopeful Clairières dans le ciel (the title of another collection of his poems). This outlook toward life is present in many aspects of the music, especially her choice and use of keys.

Lili must have identified both with the heroine, a too-tall, somewhat awkward girl who seems to evaporate into the mist, and with the narrator/lover in the poems. The key of E major, used in several songs, appears to represent the more joyous aspects of the woman and the love between the two. Songs 1 and 2 describe the heroine in a gentle, lilting way. No. 4 depicts the bubbling fountain of their love. No. 5 begins in E minor with a passionate, imploring prayer from the lover to a black virgin icon and concludes in E major, in an atmosphere of peace and consolation. No. 8 conveys the woman’s calm, passionate look, but the tonic E drops out at the end, leaving the lover (and the listener) literally “rootless.” Finally, in No.13, just before the end of the cycle, the woman’s memory is recalled with an exact repetition of the opening of song No. 1.

A second important key, D minor, is used in the last three songs to represent the sadness and finally despair of the narrator/lover over the loss of his love. The somber, static, bare chords of No. 12 convey a sense of anguished finality. The foreboding nature of D minor also pervades No. 13; attempts are made to “temper” this sadness by recalling previous music in E and C major, but in the end, D minor prevails. The final notes of the cycle, an open fifth on D, could be interpreted as emptiness, an echo of “plus rien” (nothing); or perhaps this open fifth signals ambiguity, resignation, or even a small glimmer of hope.

The key of C major appears in the cycle at moments of affirmation and as relief from the despair of D minor. In No. 11, C major even plays a triumphant role, appearing near the end in a wistful, recurring, four-note motive that becomes transformed into an affirmative forte statement. This strong ending, the only such in the cycle, accompanies the text “sur ma vie” (on my life) and serves to reinforce the theme of empathy through suffering, an important theme both of the cycle and of Lili’s life. Significantly, the wistful C major motive of No. — 6 — 11 recurs in the piano at the end of No. 13, immediately preceding the final open fifths on D, to inject a moment of hope under the final “plus rien.”

A few other examples demonstrate further how the meaning of the text is reflected in the music. In No. 3, distinct segments of music with varying tempi, keys, and accompaniment patterns match the fleeting, fluctuating emotions of the distraught lover. In No. 6, tortured chromaticisms and repeated references to the opening of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde express melancholy and disillusion, while the final resolution on F minor, accompanying the phrase “I don’t know if I will recover,” conveys an acquiescence that undoubtedly resonated with Lili. Soft, languorous chords in D-flat major (the only use of this key in the cycle) mark the centrality of No. 7, both musically and textually. The rippling accompaniment that opens No. 9 soon begins a journey toward increasingly anguished chromaticism, only to make an almost hopeful turn at the end toward D-flat major (a remembrance of the ecstasy of No. 7?), but in the final chord, the bass drops out, leaving only the upper voices fading away. The piano part of No. 10 lyrically depicts the swinging and swaying in the wind of two columbines, a little vignette providing relief, suitably in the key of C major, although C major is not established firmly until the end (most of the piece hangs on the dominant of G). In each song, chromaticism and dissonance are used freely and frequently to interrupt the prevailing mood and to indicate the lover’s agitation, pain, or anguish.

A final word should be said about the choice of thirteen songs for the cycle. This number was significant for the composer: Lili’s full name had thirteen letters in it, and she often joked about how the number was a symbol for her. Also, the monogram of “LB” that she chose for the cover of her published works resembles “13.” Thus, Lili carefully and purposefully selected thirteen poems out of Jammes’ original cycle of twentyfour.

T he other four Lili Boulanger songs on this recording represent slightly different periods in her creative output — if it is possible to discuss “periods” in a career of only seven years. Reflets (Reflections) is from 1911 and bears some affinity to the songs of Fauré in its broken chord accompaniment and tonal harmonies. Only one year later, in Attente (Expectation) and Le retour (The Return), Boulanger’s harmonic language is already more complex and chromatic, evocative of some early Debussy songs. These three songs are in the keys of F-sharp minor, C-sharp major, and F-sharp major, respectively, showing Lili’s predilection for sharp keys. In contrast, Dans l’immense tristesse (In Immense Sadness), from 1916, is in B-flat minor, a key that represented mourning and sadness to Lili during this depressed time in her life. The dark sonorities, ostinatolike accompaniment patterns on stark open fifths, and dissonant harmonies convey the anguish of the mother grieving over her dead child. Some resolution comes at the end with the quotation of a French lullaby in the piano postlude. These four pieces express again the fortitude tinged by almost-unrelieved melancholy that was a constant theme for Lili Boulanger — in her life — 7 — and in her music.

Opening this recording are three mélodies of Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924), a Boulanger family friend and important influence on the music of Lili. As professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire from 1896, and its director from 1905-1920, he taught composition to the Boulanger sisters and Ravel, among other notables. Vocalise-étude (1907) is one of three vocalises on this disc, all part of a multi-volume set of vocalises commissioned in the early years of the century, and published by Alphonse Leduc. Tristesse (Sadness, 1873) has an obvious thematic connection with the music of Lili. At age six, she reportedly sang En prière (In Prayer, 1889) at sight, with Fauré at the piano. Whether this occurred before or after the death of Lili’s father is unknown, but the fervency of the prayer and the simple profundity of the music resonates with our knowledge of the child Lili.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) and Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) are, of course, renowned figures in early 20th-century French music, and both have connections to Lili. Debussy and Boulanger never met, but they knew each other’s music and, coincidentally, died within one week of each other. Boulanger was especially influenced by Debussy’s opera, Pelléas et Mélisande (1902), based on the drama by Maurice Maeterlinck. Lili used Maeterlinck texts for Reflets and Attente; her large, unfinished project at her death was an opera on his La Princesse Maleine. Echoes of Debussy’s early harmonic vocabulary, as in his Cinq poèmes de Baudelaire (1889), of which Le jet d’eau (The Fountain) is No. 3, are heard in Lili’s later Attente. Debussy’s pianistic writing, his emphasis on sonority, and his idiomatic setting of the French language also influenced Boulanger.

Ravel met the Boulanger sisters in Fauré’s composition classes at the Conservatoire; although they traveled in the same circles, they never became close friends. Ravel’s influence on Lili’s music can be heard in her colorful writing for piano, and for orchestra. Both composers had a penchant for exoticism, an obvious trait in Ravel’s Vocalise-étude en forme de Habañera (1907). As in Bizet’s Carmen, Ravel presents a French notion of a Spanish interpretation of a Cuban dance, and a ravishingly sensuous one at that.

The last two composers on this disc, Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) and Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992), are included here because of their connections to Lili, and because they represent possible directions Lili’s music might have taken, had she lived a normal lifespan. Honegger was born in Switzerland (one year before Lili), but studied at the Paris Conservatoire (sporadically from 1911- 1918) and was part of the group of prominent French composers known as Les Six. While his musical affinities were as much German as French, some of his music, including the Vocalise-étude (1929), incorporates the popular, jazz-tinged style favored among Les Six, and some of his harmonic and melodic characteristics were foreshadowed by Lili. One other connection of note: the first recording of Lili’s music, which did not appear until 1960 and included some of her religious choral music, won that year’s Arthur Honegger Prize for religious music.

Messiaen’s connection with Lili comes through the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied organ with Marcel Dupré, a good friend of the Boulanger family and a fellow contestant with Lili for the 1913 Prix de Rome. Messiaen later taught harmony and composition at the Conservatoire. In 1965, when “Les Amis de Lili Boulanger” was formed in Paris, Messiaen was one of the luminaries on the organization’s honorary committee. One of the most prominent composers of the 20th century, Messiaen’s style incorporates colorful, dissonant, dense chords, with a weightlessness and transparency that clearly identifies it as “French.” These characteristics are present in the brief, tender, almost enigmatic Le sourire (The Smile, from Trois mélodies, 1930). A setting of poetry by Cecile Sauvage, Messiaen’s mother, it is one of his earliest published pieces, written three years after his mother died.

After studying and listening to the music of Lili Boulanger and her compatriots, inevitable questions arise: Why are the compatriots so much better known than LIli herself? Why the comparative neglect of the works of this extremely gifted woman who wrote such extraordinary music and who was so celebrated in her time?

In the years following Lili’s death, her music was periodically performed in Paris and abroad, always to great acclaim. Later, groups formed in Boston (1939) and Paris (1965) to promote Lili’s works. Still, the first recording of her music did not come until 1960, and the first (and only) comprehensive study of her life and music, Léonie Rosenstiel’s The Life and Works of Lili Boulanger, was not published until 1978. Even today, much of her music is difficult to find, in score or in recorded form, and many music lovers and musicians have never heard of her.

The reasons for this relative neglect are many and complex. Lili’s output was not particularly large, so historians have tended to ignore her in favor of her (male) contemporaries, who lived longer and wrote more. Her biographical information and scores have also been difficult to obtain, largely because of Nadia Boulanger. Ironically, Nadia’s profound devotion to her sister has prevented others from learning of and about Lili and her music. Much of the primary source material concerning Lili and many of her scores were held closely by Nadia until Rosenstiel’s research in the 1970s; additional information will likely remain sequestered until Nadia’s papers become publicly available in 2009. Many critics believed the “legend of Lili” was a sentimental myth propagated by Nadia, and that Lili (about whose music they knew very little) was much overrated. Recordings have also been rare, perhaps because so many of Lili Boulanger’s works present extraordinary difficulties for performers; they are virtuosic works, for vocalist and pianist alike, testing the extremes of range, facility, and color for both performers.

In recent years, the exploration and revival of historic women composers, inspired in part by the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, has brought new attention to Lili Boulanger. By placing her songs within the context of 20th century French music, we hope with this recording to foster increased understanding of and appreciation for the amazing originality and beauty of Lili Boulanger’s music.

Given Lili Boulanger’s strong ties to the composers and musical artists of her time, it isn’t surprising that she chose to set relatively contemporary texts to music, reflecting the ethos of her era and milieu. Beyond that, Lili’s particular experience appears to have strongly influenced her deeply personal preferences in poetry. Thus, the fervor, optimism, melancholy, and soulfulness of her music are often matched in the lyrics she selected. One can especially see Lili’s mark in the way she shortened and rearranged Francis Jammes’ poetic cycle, Tristesses (Sorrows), to suit her own artistic purposes.

The Fauré songs on this disc provide an interesting prologue and clear comparison to Lili’s — appropriately so, given Fauré’s status as her mentor. As mentioned above, Lili reputedly sang En prière (In Prayer) when quite young. The child’s petition in the song reveals complete trust in a divinely paternal (or paternally divine) figure. Lili’s own vocal works suggest both a deep desire for and some uncertainty about such simple and abiding faith.

The words to Fauré’s Tristesse (Sadness) provide an illustrative counterpoint to the last song on this disc, Lili’s Dans l’immense tristesse (In Immense Sadness). Théophile Gautier’s poem for the Fauré deploys all the commonplaces associated with budding love: springtime, roses, music, wine, and young couples arm-in-arm under the arbor. These descriptions of loveliness are punctuated with the mood-dampening announcement of the poet’s “dreadful” sadness, attributed only allusively to some unmentionable loss (“I no longer love anything”). But the sadness of one disenfranchised from humanity and even from his own soul doesn’t quite reach the “immense” sadness of the later song by Lili. Whereas the “grave” in Fauré’s work is figurative, in Boulanger’s piece it is quite literal and the loss explicit. An onlooker’s description of a mother’s night-time visit to a cemetery, much of the song’s poignancy arises from the sentiment-charged image of the death of a child, his misunderstanding of his own death, and the mother’s effort to maintain the pretense of a living relationship. The song bespeaks more than sadness; there is an anxious edge to the onlooker’s questions. He assumes at first that the cemetery is a place of peace when it is, in actuality, the mother who brings peace from the world of the living to the child’s troubled soul. The words must have resonated with Lili’s experience of a close and vital parent-child relationship, like that prefigured in En prière. For both Lili and the figures in her song, however, death complicates this simple relationship.

Maeterlinck’s words to Boulanger’s Reflets (Reflections) are lovely, evocative, and — in good Symbolist style — not too ambiguous. Water is used as a metaphor for dreams which are both unreal and reflective of unknowabout the lyrics notes by Eilene Hoft-March — 10 — able realities. Water is also the mediating surface that suggests, by its powers of reflection and penetrability, the vast firmament above and the depths of the heart and soul beneath. The two realms (heaven and heart) are not only mirrored but also linked: the moon, for example, illuminates the human heart “plunged in the source of the dream.” The last image, of dropping flower petals, a sure sign of transience, inverses the petals’ descent below water to make them rise “eternally” to the reflected moon. The optical/intellectual illusion of the human soul being connected to the cosmos is both evoked and challenged. The fade into silence which concludes the piece suggests that Lili adopts the darker suspicion.

Although Francis Jammes has been very loosely classified as a Symbolist, his work has little in common with the rich ambiguities of Maeterlinck, much less with the dense and murky abstractions of Stéphane Mallarmé. Jammes’ poetry is spare, clear, and highly visual. The cycle of his poems Lili chose to set, Tristesses (Sorrows), rehearses themes that go back to the tradition of medieval French courtly love: the poet’s obsession with a beloved woman, the unresponsive or reticent woman lover, and the suffering of the poet at the loss of the beloved, in this case, to death. In light of Lili’s artistic preferences and her own personal circumstances, one might wonder what most attracted her to Jammes’ cycle. Was it the poetry’s latent sensuousness? Or, quite differently, its subtle religious overtones? We know that Lili explicitly identified herself with the female figure in the poems, whom she further associated with Maeterlinck’s heroine, la princesse Maleine, who spends her life in isolation from the people and activities she loves — as did Lili.

As mentioned earlier, Lili modified the cycle to make the poetry more her own. She substituted another Jammes’ title, Clairières dan le ciel (Clearings in the Sky), for Tristesses, a change that brought with it religious connotations of hope. In addition, Lili used only thirteen out of twenty-four poems in her cycle, and reordered the ones she did choose. These “editorial” decisions significantly changed the work’s complexion. For example, Lili dropped from the cycle a number of love poems (I have someone in my heart; Come under the arbor; Come, my beloved). Lili’s arrangement of the remaining thirteen poems creates a clear upward movement toward the seventh and central song, Nous nous aimerons tant (We will love each other so much), balanced by an emotional downturn to the last song, Demain fera un an (Tomorrow it will be a year).

The first song in Lili’s cycle illustrates her appropriation of Jammes’ work. Jammes’ first poem (which Lili omitted) begins “I desire her.” Lili avoids that cautiously lustful overture, beginning instead with the second poem: Elle était descendue au bas de la prairie (She had gone down to the bottom of the meadow), a song heavily laced with floral motifs. In Jammes’ series, having started with desire, the poet’s flower picking early in the poem suggests, somewhat unsubtly, other kinds of flower picking. By dodging the first poem, Lili softens the poet’s intimations and puts the focus much more on the female figure. Lili’s cycle begins with “elle” (she) instead of “je” (the masculine “I”). “Elle” is also the letter L in French, — 11 — Lili’s first initial. To reinforce the link, water lilies — Lili’s personal symbol — appear at the poem’s end. The poem portrays a rather unconventional woman: too tall, awkward yet graceful, and lively. Other poems in the cycle describe her as possessing an inquiring and penetrating mind, a limpid soul, and a sealed heart with a single passion. Altogether, an appealing and not-at-all inaccurate description of Lili.

The fourth song, Un poète disait (A poet said), offers another example of Lili’s appropriation of the poetry to her own ends. The poem reprises a familiar dynamic: woman inspires, poet writes — and the production verges on prolific. Verses flower like roses on a rosebush; water gushes from an inexhaustible source. The poet aspires to divine acts in which he would give the woman “the color of a perfume that will be nameless.” The poet wishes to create with words a visual scent beyond language, bright and penetrating, intangible and ineffable. But what the poet can only “wish” for his beloved, and cannot make with his words, the composer can accomplish on her own: producing a musical coloring, a surrounding impalpability, a wordless scent. Lili’s version gives an interesting twist both to media (words vs. music) and gender roles.

Nous nous aimerons tant (We will love each other so much) marks the midpoint and emotional highpoint of Lili’s cycle. The song projects a reunion of the couple in a familiar place and a gentle intimacy requiring neither words nor touch, only the evocative gesture of hands outstretched to one another. The poem is set in an undetermined future, placing it apart from all the others in the cycle, which are firmly anchored in the poet’s present or — especially as the work draws to a close — in a greatly regretted past.

The ninth song, Les lilas qui avaient fleuri (The lilacs that flowered), presents another interpretation redoubled and enriched by the composer’s perspectives. Jammes has again chosen a floral décor, this time an orchard in bloom. According to long literary tradition, orchards serve as a favored trysting place, and this one is no exception. The Jammes persona has come in hopes of “I don’t know what, from you” — some indeterminate desire — or so he says. Moreover, while mulling over this “je ne sais quoi,” he has placed his soul in the beloved’s lap. We inevitably visualize the poet’s head (not his soul) in the woman’s lap: the quintessential Victorian pose of intimacy. By substituting a soul for a head, Jammes spiritualizes and transcendentalizes the contact, something Lili surely appreciated. The poet is clearly concerned about rejection (“don’t push [my soul] away”); but the unexpected justification for this appeal is that the poet’s soul might otherwise see how “faible et troublée” the beloved is. Here we must look to the original French to catch his drift. “Faible et troublée” can certainly be translated as “weak and troubled,” but in a vaguely erotic situation, there are additional connotations: “faible” connotes sexual vulnerability and “troublée” can mean “aroused,” “disturbed,” “embarrassed” — or all three at once.

While there exists no direct evidence of Lili’s — 12 — thwarted love life, the poem generates a second cluster of meanings that fits what we know of the composer’s life and temperament. Lili surely would have associated herself with the lilacs of the title, and other fragile flowers that bloom in sorry little flowerbeds and on frail peach trees. Lili — much more than Jammes — must have reflected on unfulfilled expectations and on the grand “je ne sais quoi” of a life lived on the edge. How much more urgently might Platonic intimacy have replaced not just desire but a sense of mortality that, uncurbed, would have left her weak and troubled indeed.

Deux ancolies (Two columbines) and Par ce que j’ai souffert (Because of what I have suffered) are poems seemingly made for Lili. They feature relationships not between lovers, but rather between female friends. Surely the poems spoke meaningfully to Lili, who relied so heavily — physically and emotionally — on her friend Miki Piré, her sister Nadia, and her mother. In Deux ancolies, “sister” flowers pummeled by the elements confess to their common fears, an admission that only serves to strengthen their affections. The second song develops the same notion of love born of adversity. Sisterhood expands into a relationship between the caring and the cared for, closely bonded through pain and illness. The second poem adds another dimension: the poet observing another relationship like his own (he confides, “for I was two”). The experience of suffering thus catalyzes a network of empathic understanding.

The last text for both cycles, Demain fera un an (Tomorrow it will be a year), descends into genuine despair over the death of the beloved. But the poet and the composer approach this death from very different vantage points. The poet’s is one of retrospection: he reminisces with nostalgia and pain about his loss. Lili — who identified with the beloved flower-woman — is in the present but anticipates an imminent future in which she will be dead. The songs that conclude the cycle seem to take us irrevocably down to that death — or do they? Is the substituted title, Clearings in the Sky, sufficient to suggest hope? Should we take the musical quotations of the first song that resurface in the last as a return to an earlier point in the cycle? One hopeful sign is Lili’s careful rearrangement of the texts to place at the heart and soul of the cycle the seventh song: The only song set in an unspecified future, it promises a union bright with enduring love and companionship, beyond time’s ravaging grasp.

Eilene Hoft-March teaches French and Gender Studies at Lawrence University, and writes on twentieth century French literature, particularly autobiographies written in the second half of the century.

Album Details

Total Time: 76:35

Recorded: June 12-15, 2000 in Harper Hall at Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover Photography: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Rebecca Rollins & Eilene Hoft-March

© 2000 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 054