Store

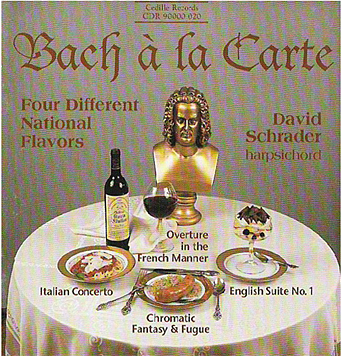

Harpsichord CDs typically serve up a heaping portion of a composer’s closely related works. On this CD, however, Chicago’s David Schrader presents a platter of four differently-seasoned Bach compositions.

The disc opens with the lyrical Italian Concerto in F Major, BWV 971. In the program notes, Schrader describes this piece as “the apotheosis of Bach’s many transcriptions from the works of many Italian composers.”

The ornate Overture in the French Manner, BWV 831 (also known as the Partita in B minor), emulates the ornamentation, forms, and melodic inventions of the French style of the first half of the 18th century.

The meat of the program, the brilliantly improvisatory Chromatic Fantasy & Fugue in D minor, BWV 903, is quintessentially German and propelled by virtuosity.

The stately English Suite No. 1 in A Major, BWV 806, generally available only in a complete set of the six English Suites, seems predominantly French in its ornamentation, but with a thicker texture that suggests a German heritage. (How this stylistic hybrid and it’s companion suites became known as “English” remains a mystery; it wasn’t Bach’s idea.)

The entire Bach á la Carte program could be called “chromatic,” with its extraordinarily wide range of colors owing to the instrument, Schrader’s playing, and Bach’s writing, observes Cedille producer Jim Ginsburg.

The double-manual harpsichord used in the recording was built in 1992 by Paul Y. Irvin of Glenview, Illinois. Its acoustical design is modeled on a 1638 Flemish instrument.

Preview Excerpts

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750)

Italian Concerto in F major, BWV 971

Overture in the French Manner, BWV 831

Chromatic Fantasy & Fugue in D minor, BWV 903

English Suite No. 1 in A major, BWV 806

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe International Bach

Notes by David Schrader

Johann Sebastian Bach did not enjoy the internationally peripatetic career of his famous colleague, George Frederic Handel, whom one might call a German composer, trained in Italy to compose Italian operas for an English public. Bach’s travels, by contrast, were limited to a small regional area encompassing East-central Germany. Nevertheless, Bach demonstrated a keen interest in international affairs where questions of musical taste were concerned. Bach had a wide ranging knowledge of virtually every musical trend extant during his life and of many older styles as well. He transcribed for harpsichord and for organ many of the works of Antonio Vivaldi. Bach also copied for his own reference the 1699 Livre d’Orgue of Nicolas DeGrigny, the sometime organist of Rheims cathedral. Bach’s own music evinced a constant synthesis of Italian and French styles and forms with the harmonically generous and contrapuntally developed musical language characteristic of his fellow German-speaking composers.

The Concerto nach Italiaenischem Gusto (Italian Concerto), BWV 971 and the Overture nach Französischer Art (Overture in the French Manner), BWV 831 comprise the second part of Bach’s Clavierübung, or keyboard study, of 1735. Both pieces require a harpsichord with two keyboards and reflect the prevailingly popular foreign tastes of the German-speaking world of the time. The Concerto was favorably reviewed in 1739 by the noted theorist Johann Adolf Scheibe (who was not always a proponent of Bach’s music):

Indeed, who could deny that this harpsichord concerto should be taken as the perfect model of a well-made concerto for one instrument? It is certain that today there are few, if any, concertos with such remarkable qualities or so imaginatively constructed. Only a great master of music such as Mr. Bach, who has almost appropriated the harpsichord for himself and thanks to whom we can safely challenge those of other nations, could have given us such a work, which deserves to be emulated by all our great composers, but which foreigners may seek to imitate in vain.

The Concerto represents the apotheosis of Bach’s many transcriptions from the works of Italian composers. The contrast of solo and tutti textures are given over to the interplay between the two keyboards of the harpsichord, which Bach indicates with requests for piano and forte. The ritornello form associated with baroque concerti is crystal clear, and the Italianate ornamentation of the second movement is a paragon of that tradition.

The Overture in the French Manner, or (as it is also known) Partita in B minor, is equally successful in its design to emulate the ornamentation, forms, and melodic invention of the French style of the first half of the eighteenth century. The “Overture” (first) movement itself, however, is a hybrid that incorporates the form of the standard French overture with the ritornello form of the Italian concerto overlaid. Throughout the piece, Bach indicates the need for two keyboards with passages marked piano and forte, taking special advantage of the properties of the double-manual instrument in the unique final movement, tellingly titled “Echo.”

The Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, BWV 903 probably belongs to the years Bach spent in Cöthen (1717-1722). Here the listener is presented with a work that is wholly German and of a style already well-known and venerated in Bach’s lifetime. The later epithet, “chromatic,” probably reflects both the far-ranging modulations of the extravagant Fantasy and the obvious nature of the Fugue’s subject. The impovisatory character of the Fantasy comes from a long tradition of pieces composed in the stylus phantasticus, a genre in which the musician can demonstrate uninhibited invention. In his Musurgia universalis of 1650, the German composer and theorist Athanasius Kircher, offers an excellent definition of this style:

The fantastic style is suitable for instruments. It is the most free and unrestrained method of composing; it is bound to nothing, neither to words nor to a melodic subject; it was instituted to display genius and to teach the hidden design of harmony and the ingenious composition of harmonic phrases and fugues; it is divided into those pieces that are commonly called fantasias, ricercatas, toccatas, sonatas.

From the outset, the Fantasy proves a bravura piece of truly marvelous invention. The brilliance of the instrument itself is evident in every phrase: the piece abounds in arpeggios and fast scales, and even includes a section marked “Recitativ.” The Fugue, while rather more strict, is still propelled more by virtuosity than by contrapuntal devices. To both listener and performer, this work, probably more than any other, suggests Bach in a flight of improvised inspiration.

The English Suite in A Major, BWV 806 is almost certainly the earliest work heard on this recording. Most recent research puts the English Suites at the end of Bach’s Weimar period (1712-1717). The form, idiom, and melodic content of these six suites show Bach having already mastered the French and Italian styles of the day. Unfortunately, no clue is available as to the application of the word “English” to these pieces. This distinction did not come from Bach, and the possibility of a dedication to an English patron is geographically and logistically untenable.

The Suite in A Major, with its French titles, copious use of the stile brisé (which uses broken chords as figurations while constantly inserting filler notes to amplify the texture) in the manner of French harpsichord composers, seems to fall squarely into the French “style” camp. The ornamentation is entirely French: musical decorations consist largely of short trills and mordents rather than the elaborate connecting passages more characteristic of Italian ornamentation. Although the names of the dances are French, the pieces themselves often incorporate a texture rather thicker than that of their French counterparts, thus betraying their German heritage. Of particular interest is the indication to play piano (softly) at the end of each half of the concluding Gigue, constituting a rare preference for a harpsichord with two keyboards, especially surprising in a work this early in Bach’s output.

— David Schrader

Album Details

Total Time: 77:15

Recorded: June 15 & 16, 1994 in Ganz Hall at Roosevelt Universitys Chicago Music College

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Photograph by Erik S. Lieber. Styling by Christianne Ingegno

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: David Schrader

©1994 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 020