Store

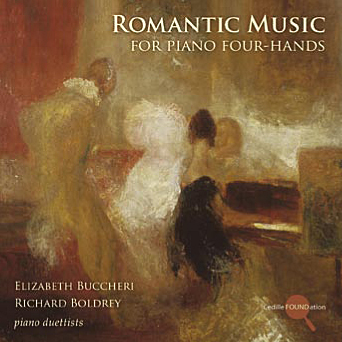

Noted piano duettists Elizabeth Buccheri and Richard Boldrey offer a fascinating collection of piano duet music by composers spanning the 19th century including two sonatas by Georges Onslow (1784–1853), a Suite by Balakirev, and shorter works by Reger, Grieg, Liszt, and Wagner(!). These brilliant performances, which previously appeared on two separate LPs, were digitally remastered from the original reel-to-reel tapes from 1978 and 1985 for optimal sound quality.

“This record is a winner…. Boldrey and Buccheri don’t just play the notes. They enjoy the music, and convey that enjoyment tangibly…. This is one of those sleepers… every time you feel like some unalloyed enjoyment, you’ll consider pulling this disc down and playing it.”

— Fanfare on the original LP issue of Romantic Music for Piano Four-Hands

Preview Excerpts

GEORGES ONSLOW (1784 - 1853)

Sonata No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 7 for Piano Four-Hands

MAX REGER (1873 - 1916)

from Six Burlesques, Op. 58

RICHARD WAGNER (1813 - 1883)

FRANZ LISZT (1811 - 1886)

EDVARD GRIEG (1843 - 1907)

from Norwegian Dances, Op. 35

MILY BALAKIREV (1837 - 1910)

Suite for Piano Four-Hands

GEORGES ONSLOW

Sonata No.2 in F Minor, Op. 22

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletRomantic Music for Piano Four Hands

Notes by Janice Marciano

The nineteenth century gave rise to an abundance of music for piano four-hands that included not only transcriptions and adaptations ranging from the Brandenburg Concertos to Stravinsky’s Fireworks but also a large and at times highly masterful original repertory for the medium. If its beginnings a century and a half earlier were tenuous, we can attribute that to the impracticality of having 2 performers play on a small keyboard of limited range. The insurgence of four-hand literature in the nineteenth century, as with solo keyboard repertory, parallels the development of the instrument itself, especially with regard to range.

The manner of notating Primo and Secundo parts also underwent a gradual evolution. At first the concept of right hand playing treble clef and left hand bass was retained in the pairing of two grand staffs. To avoid crossing hands between the players, however, the actual notation was often confined either to the treble staff for the Primo or the bass staff for the Secundo leaving the two middle staves empty. By the time of J.C. Bach, the Secundo part was now notated on two staves in bass clef and, soon after, the Primo was likewise notated in treble.

The technique of writing for four hands required thinking in terms of twenty fingers disposed over the entire keyboard rather than joining two solo parts. For example, early works show frequent doubling of material two octaves apart. This gradually gave way first to a more sonorous combination of thirds and sixths, and later to a varied disposition of material with, perhaps, melody for the top Primo line, a stable, supportive bass for the low Secundo line, and different accompanying figures for the two inner lines. Early attempts at imitation also opened up later possibilities of more sophisticated double counterpoint, frequent examples of which are heard in the works of Brahms and Dvorák.

The first extant piano duets are by two Englishmen, Nicholas Carleton and Thomas Tomkins, and date from the first half of the seventeenth century. It would take another 100 years, however — when we meet the four-hand Sonatas by J.C. Bach (the London Bach who strongly influenced Mozart) — for there to be any real activity in the composition of music for piano duet. The first published work for the duet medium appeared in 1777: the Sonata in F Major from Duets for Two Performers upon one Instrument by English composer Charles Burney, who in his Travels gives an account of the young Mozart performing together with his sister Nannerl.

From these modest gestures (among others) the concept of four-hand playing and its literature was off to a healthy start. In a brief survey of the years that follow three points stand out as significant artistic achievements, interpretatively and structurally, for piano duet: Mozart, Schubert, and Brahms/Dvorák. The directions set by these men spurred a rich variety of material by other composers of both major and minor stature.

As early as 1765, before the Sonatas of J.C. Bach, the 9-year-old Mozart had written a sonata for four-hands. His other works include a fantasy composed for mechanical organ and transcribed for four hands, a set of variations, and, most important, four mature sonatas, including the masterpiece in F Major, K. 497.

Beethoven appears to have found the genre of less interest. He did leave two sonatas, two sets of variations, and a set of marches, Op. 45, for piano duet. All but one of these works are confined to his early years of creativity (the Marches date from around the time of the Eroica Symphony) and generally reflect a lighter mood.

The largest output of four-hand literature comes from the prolific pen of Franz Schubert and includes overtures, dances, fantasies, rondos, variations, marches, sonatas, and other miscellaneous works. The Grand Duo in C, D. 812, so orchestral in nature, is thought to be an arrangement of an intended symphony. The Fantasy in F Minor, D. 940, is considered one of the pinnacles of the four-hand repertory. Walter Georgii, whose thorough study, Klaviermusik, may well be the definitive one-volume book on piano music, points to this (along with Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy for solo piano) as the example of the true spirit of the Classic sonata captured by a Romantic figure.

Schumann’s representative works are perhaps not among his best inspirations. Some of the material in the Polonaises, Op. 3, for duet, suggest that they were written as a study for the Papillons, Op. 2, for solo piano, both dating from his early years. The other four-hand pieces, Pictures from the East, 12 Four-hand Piano Pieces for Big & Small Children, Ballszenen, and Kinderball, are products of Schumann’s later years of illness which, though alive with inventive ideas, nevertheless reflect the decline that affected his composition.

The importance of sonata form as a structural element diminished by the mid 1800s. In the list of works by Schumann no sonatas for duet appear; the same is true for Brahms and Dvorák, both of whom concentrated their interests in dances. Dvorák, the Czech contemporary of Brahms, wrote several works for piano four-hands, in particular the two superb sets of Slavonic Dances and a group of highly poetic pieces entitled Legends. Brahms’s works include several sets of waltzes, originally written for four hands and later transcribed either for two hands (Op. 29) or for the addition of voices, as with the Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 52. His Hungarian Dances, perhaps more familiar in their orchestral version, were composed originally for four hands. Brahms also arranged the Schubert Waltzes for piano duet. This liberal attitude toward arrangements and rearrangements is in keeping with the social interest in informal music making common during the latter part of the 19th century.

Chopin’s two works for duet, Mendelssohn’s Allegro Brillant, which he performed with Clara Schumann, Weber’s three sets of charming duet music, themes from which served as the basis for Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphoses (1943), and the numerous duets of Reger give a fuller, though by no means complete, picture of the four-hand repertory.

While Balakirev, Grieg, Liszt, Onslow, Reger, and Wagner do not represent the major composers of this genre, each of their works brings interest and delight. Georges Onslow is perhaps the least known of the composers presented here. An Englishman born in France, all of his nine known piano sonatas were composed before 1829. Two of these are for four hands: Op. 7 in E Minor and Op. 22 in F Minor. Typical of Onslow’s style, the “Grand Sonata” in E Minor is a highly expressive work, unified and well developed with regard to harmonic and melodic structure.

“Like so many composers who have made a great name for themselves in their own country and not yet elsewhere, Reger is something of an acquired taste for foreigners who have the problem of seeking out a perspective that will show him in his best light. But he is an authentic composer whose music teems with ideas, harmonically, contrapuntally and pianistically.”

— The Piano Duet by Ernest Lubin

Reger’s four-hand works do show him at his best, the Burlesques, Op. 58 (1901) especially so. These virtuoso pieces, whose brevity tends to make one overlook their remarkable construction, are filled with interesting ideas imaginatively worked out. Reger exhibits some rare, typically Germanic humor in No. 6, where the familiar tune Ach du lieber Augustin plays a significant role, allowing the composer an opportunity for serious contrapuntal display in the lightest of contexts.

The Polonaise in D by Wagner is an interesting example of the great opera composer’s early work. Composed in 1831, it offers little glimpse of the Wagner to come, looking back instead to the lightness and charm of Carl Maria von Weber.

Liszt wrote only one piece for piano four-hands, the Fest-Polonaise, on the occasion of the marriage of Princeess Marie of Saxony. This exists in no other form. The Grand Valse di Bravura, Op. 6, on the other hand, was originally an early solo concert piece, and its four-hand arrangement leaves some doubt as to its origin. The waltz is Chopinesque in style, but its brilliant coda shifts rhythm, gaining dynamic intensity and momentum toward its close.

Grieg’s Norwegian Dances, Op. 35 (1881) take their motives, as do many of his folk-inspired works, from the collection Mountain Melodies compiled by Ludvig Lineman. The dances are examples of the halling or fling dance. These delightful pieces, which sound more effective in their original four-hand keyboard setting than in the popular orchestral versions (by Hans Sitt), show Grieg at his finest: he evokes magical landscapes through colorful pianistic touches and harmonic turns of extraordinary piquancy.

Balakirev, one of the Russian “Mighty Five,” is known particularly for his Islamey for solo piano. His four-hand Suite of 1908 is in three movements — Polonaise, Chansonette sans paroles, and Scherzo — and is his only work for piano duet (other than an arrangement of 30 folk songs originally composed for voice and piano).

The second of Onslow’s two four-hand sonatas dates from around 1820. Like its companion, it represents a high point of the piano duet repertory, typically melodious, well-constructed, and perfectly conceived for the medium. Onslow shares with Mendelssohn that sense of effortless writing in which we never feel the slightest hesitancy or lack of forward direction. Georgii rates Onslow highly and singles out this sonata’s second movement as “a pearl… forerunner of those movements that Brahms favored as substitute for minuet or scherzo in his chamber and symphonic works.” What a pity that such a beautiful piece has fallen into obscurity.

Currently on the faculty of the Emma Willard School in Troy, NY, and director of the Music in Central Valley chamber music series, Janice Marciano is active as a piano soloist and chamber musician in the greater New York metropolitan area.

Album Details

Total Time: 76:26

Recorded November 1978

(Onslow Sonata No. 1, Liszt, Wagner, Balakirev) and March 1985 (Reger, Grieg, Onslow Sonata No. 2) at North Park University, Chicago.

Original Session Engineer: Charles B. Hawes

Remastering: Bill Maylone

Reissue Producer: James Ginsburg

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover: Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 – 1851),

Music Party, East Cowes Castle. Ca. 1835. Oil on canvas, 121.3 x 90.5 cm. © Tate, London / Art Resource

This CD reissue was made possible in part by a special grant from the Alumnae of Northwestern University Gifts and Grants Committee.

© 2009 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 7002