Store

Store

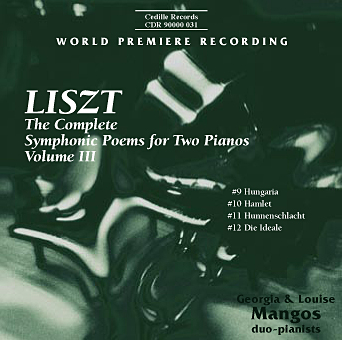

Liszt: The Complete Symphonic Poems for Two Pianos – Vol. III

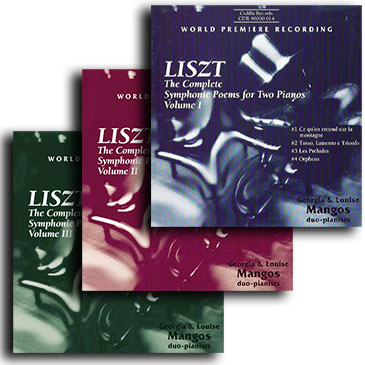

This is the final volume in our historic collection of Liszt’s own two-piano versions of his 12 symphonic poems from the Weimar period (1848-61). The 3-disc series comprises the first complete recording of these works, most of which had disappeared from the repertoire by the turn of the century.

“Returning Liszt’s two-piano versions to the concert repertoire has been a long and thrilling journey for us,” the Mangos sisters write in the program notes. “We’re convinced that these landmark works are as vibrant and emotionally compelling as ever.”

The Mangos sisters have been performing the Liszt in concert with gratifying results. “These works really have the ability to ignite an audience,” Louise Mangos says. “It’s unusual to get a robust, standing ovation for music that hasn’t been heard in 125 years. But audiences respond to these works as if they were familiar favorites.”

The Chicago-area concert pianists and music professors discovered the scores, which have never been published in modern versions, while scouting for duo-piano repertoire in European libraries, collections, and music shops.

The first Liszt CD released in June 1993 received such comments as: “stunning”, “absolutely smashing,” and “sensitive, virtuosic and idiomatic.” The Chicago Sun-Times praised the second disc, released in October 1995, for its “astounding heavy metal pianism” and “almost surreal musicianship and interpretation.”

On the third CD, the Mangos sisters perform the folk and Gypsy-imbued Hungaria, which resembles an expanded version of one of the Hungarian Rhapsodies (on Cedille’s Liszt for Two) the powerfully compact and eerily ethereal Hamlet; the furious, then contemplative Hunnenschlacht (Hun’s Battle), inspired by a mural depicting a battle “so fierce that the spirits of the dead were seen continuing to fight in the sky” (from the program notes); and the joyful, brooding, and ultimately splendorous Die Ideale, based on Schiller’s poem of disillusionment and spiritual attainment.

“Liszt’s two-piano transcriptions of his tone poems are monumental in scope,” writes former Piano Quarterly publisher Robert Silverman in the CD notes. “These major works take on a whole new meaning when the musical palette is pared down to its essentials. The architecture and various melodic strands are clear to the ear . . . Yet the use of two pianos allows for great outpourings of sound — comparable to that of a full orchestra.”

“I’m not sure [Liszt] conceived the piano as having any limit of coloration,” Louise Mangos said in an interview with Fanfare’s James Reel. Reel echoed other reviewers in commenting, “The riveting Mangoses performances make a far better case for these works than the three integral orchestral cycles I have heard.”

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

Artists

1: The Symphonic Poems for Orchestra of Franz Liszt as Transcribed for Two Pianos by the Composer

Program Notes

Download Album BookletNotes On The Program

Notes by Georgia and Louise Mangos

Symphonic Poem No. 9: Hungaria (1854)

This symphonic poem was composed in response to the poem of homage that Mihaly Vorosmarty addressed to Liszt in 1840 for his first and most triumphant return to Hungary (he left as a child prodigy in 1821). His return was so cherished that the nation presented him with its famous “Sword of Honor”.

Of all the symphonic poems, Hungaria reflects most directly the Hungarian elements of Liszt’s compositional style, and even shares material with his nationalistic Heroic March. Its long rhapsodic sections are reminiscent of Gypsy violins, while the central march theme reflects Hungary’s native music in both rhythmic shape and tonal structure. Its lyrically improvisatory nature makes it sound much like an expanded version of one of the Hungarian Rhapsodies.

The sectional headings in the score give the impression of a war legend, and the music supports this idea. The soulful opening laments suggest an outcry from Hungary’s oppressed masses. The various “March” sections that follow imply a “call to arms”. Several battles ensue, marked by increasingly powerful climaxes. Liszt accelerates tempo and volume through octave doubling and registral changes as the battles become more frequent and intense. A tender tribute to those lost follows. This section, titled “Funeral March”, contains a gorgeous single-voiced melody first heard in the bass. When this melody is transposed up several octaves, it suggests a wailing cry for those fallen in battle. A final march sequence occurs with a stunning crescendo of matched chromatic octaves between the two pianos culminating in the “Allegro Trionfante” section, marking the soldiers’ triumphant return. The final “Presto Giocoso” presents a playful Hungarian folk melody and ends with a military flourish.

This most exciting work enthralled the audience at its premiere on September 8, 1856, when Liszt conducted the symphonic version at the Hungarian National Theatre. Liszt wrote afterwards, “There was better than applause. All wept, both men and women!” As performers, we feel the excitement behind this work will not diminish in the years to come.

Symphonic Poem No. 10: Hamlet

This is a remarkable work for several reasons. First, the poem deals with the psychological profile of Hamlet as a character, not just the well-known story line. The work is also fascinating for what is not there: it is relatively short in length and spare in texture — a distinct departure from Liszt’s tendency towards large, unfolding forms. The frequent silences and dramatic pauses are breathtaking, while the sparse textures (outside the Allegro sections) are almost otherworldly in atmosphere. This ethereal quality baffled most conductors and listeners in Liszt’s time. Hans von Bülow, a student and strong supporter of Liszt, wrote of conducting Hamlet: “Frankly, I do not regard myself as sufficiently capable of interpreting [Hamlet] as [it] require[s]”. Later Bülow pronounced the piece “unperformable”.

Although Hamlet does not conclude the cycle of twelve symphonic poems from the Weimar period numerically, Liszt wrote it last, after seeing the play performed in Weimar in 1856. Liszt conceived the piece as an overture to the play, but it was never performed as such. Its first performance did not come until 1876 at Sonderhausen, more than twenty years after its composition.

The depiction of the play’s action is not essential to the music; rather, the work deals with how Hamlet’s mind is tormented by his father’s murder. The opening statement sounds fearful and uncertain; it seems to ask, “Who goes there?” The rumblings of the second piano part give a ghostly response: the voice of Hamlet’s father. As in the opening of the Allegro Appasionatoed Agitato Assai section, it creeps up on the listener, only to unleash a whirlwind of octaves. The triplet theme that follows evokes a sense of inevitability, as though Hamlet’s actions are fated long before they happen. Hamlet’s ghostly father is always with him, reminding him and demanding that he take action.

At the end of the second large Allegro section, the murder of Claudius is portrayed. Strident, crashing chords depict the violence of Hamlet’s action, followed by a long silence. The questioning theme returns, and once again the otherworldly rumbles respond: the ghost is still with us. After the pesante lugubre “fate” theme, a death-rattle-like tremolo is followed by high-pitched unison octaves, sounding more like a shriek of horror than notes from a piano! The plaintive, questioning theme and deadly dark response return. There is a final shriek of horror, followed by two unison octaves and a final silence. Is this simply Hamlet’s death, or the ghosts of his uncle and father driving him to madness? The listener must decide.

Symphonic Poem No. 11: Hunnenschlacht

Written in 1857, Hunnenschlacht (Huns’ Battle) was inspired by a huge William von Kaulbach mural, depicting the 451 A.D. battle between the pagan Huns under Attila and the Christian forces of Emperor Theodoric for the capture of Rome. Kaulbach’s works were of such keen interest to Liszt that he once considered writing a series of tone poems after the painter’s frescoes, which included Tower of Babylon, Nimrod, Jerusalem, and The Glory of Greece. The battle represented in the Hunnenschlacht fresco is said to have been so fierce that the spirits of the dead were seen continuing to fight in the sky. Liszt had originally intended to depict that idea, but later decided instead to end the work with a full-blown version of the chorale Crux fidelis to represent the victorious Christians.

The work is in two large sections. The first depicts the battle itself, with militaristic themes and horn call motifs thrown wildly back and forth between pianists. The second section develops the chorale theme. One of the most striking moments comes as the music divides into two seemingly separate compositions. One features dotted rhythms that continue the feel of battle, while the other presents an ancient plainchant theme — calm in the midst of a storm of chaos. The effect is most powerful.

Symphonic Poem No. 12: Die Ideal

Die Ideal, written in 1857, was first performed (along with the Faust Symphony) at a concert in Weimar in honor of the laying of the foundation stone for a memorial to Goethe’s patron, Grand Duke Karl August, and the unveiling of memorials to Goethe, Schiller, and Wieland. Various excerpts of Schiller’s poem of the same name appear throughout the score. They guide us through the various moods of the work. Liszt evidently considered his musical intent more important than a faithful account of Schiller’s poetry for he changes the order of the poetic selections. Towards the end of the work Liszt even wrote, “I have allowed to add to Schiller’s poem by repeating the motifs of the first movement joyously and assertively as an apotheosis.” The ending departs totally in intent from Schiller’s. It is here that we realize we are learning more about Liszt’s personal journey than Schiller’s.

The opening section represents the joy of youth, when one is filled with courage, never fearing tomorrow’s hurdles. Then come disappointments: loves lost, friends who were not faithful, and the fear of being alone. The final section, Apotheose, is where Liszt departs from Schiller’s poem. Here, Liszt elevates the soul of a mortal to that of a God. This is mankind’s shining moment, when he sheds his fear of extinction and becomes immortal. Liszt was conscious of his role as a great composer and pianist and wanted to project the idea that his work would survive and become even more vital as time passed.

Returning Liszt’s two-piano versions of the twelve symphonic poems from the Weimar period to the concert repertoire has been a long and thrilling journey for us. Having completed the “tour”, we are convinced that these landmark works are as vibrant and emotionally compelling as ever.

Album Details

Total Time: 65:17

Recorded: August 28, 30, & 31, 1996 in Mandel Hall at the University of Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Lawrence Rock

Cover: “Two Pianos” – Glass Block Impression by Erik S. Lieber

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Robert Silverman; Georgia & Louise Mangos

© 1997 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 031