Store

Store

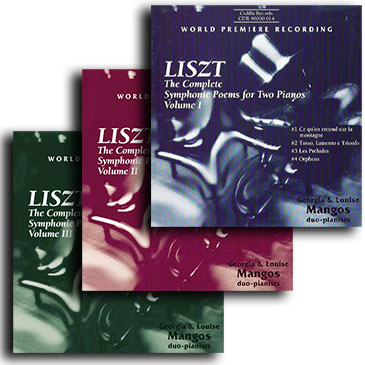

Liszt: The Complete Symphonic Poems Volumes l-lll (Box Set)

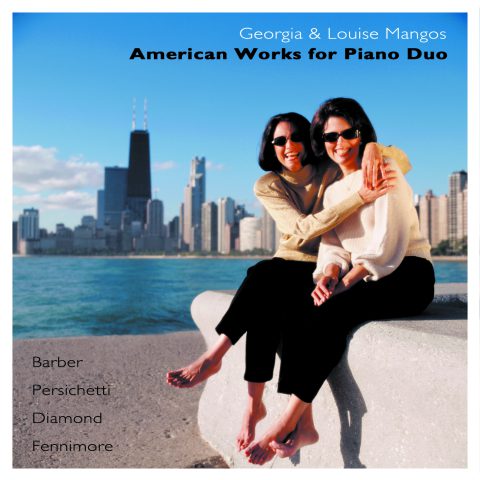

“I gave fairly extravagant praise to the playing of the Mangos sisters in their first disc . . . They almost convinced that this really was intended for two pianos rather than orchestra . . . Further listening reinforces that impression . . . The two Mangos interact wonderfully well with one another. Again, the Cedille recording is of demonstration quality.” (American Record Guide)

“One can only hope that Cedille has further plans for this enormously talented duo.” (Fanfare)

All 3 volumes of our historic collection of Liszt’s own two-piano versions of his 12 symphonic poems from the Weimar period (1848-61). The 3-disc Box Set comprises the first complete recording of these works, most of which had disappeared from the repertoire by the turn of the century.

“Returning Liszt’s two-piano versions to the concert repertoire has been a long and thrilling journey for us,” the Mangos sisters write in the program notes. “We’re convinced that these landmark works are as vibrant and emotionally compelling as ever.”

The Mangos sisters have been performing the Liszt in concert with gratifying results. “These works really have the ability to ignite an audience,” Louise Mangos says. “It’s unusual to get a robust, standing ovation for music that hasn’t been heard in 125 years. But audiences respond to these works as if they were familiar favorites.”

The Chicago-area concert pianists and music professors discovered the scores, which have never been published in modern versions, while scouting for duo-piano repertoire in European libraries, collections, and music shops.

The first Liszt CD released in June 1993 received such comments as: “stunning”, “absolutely smashing,” and “sensitive, virtuosic and idiomatic.” The Chicago Sun-Times praised the second disc, released in October 1995, for its “astounding heavy metal pianism” and “almost surreal musicianship and interpretation.”

On the third CD, the Mangos sisters perform the folk and Gypsy-imbued Hungaria, which resembles an expanded version of one of the Hungarian Rhapsodies (on Cedille’s Liszt for Two) the powerfully compact and eerily ethereal Hamlet; the furious, then contemplative Hunnenschlacht (Hun’s Battle), inspired by a mural depicting a battle “so fierce that the spirits of the dead were seen continuing to fight in the sky” (from the program notes); and the joyful, brooding, and ultimately splendorous Die Ideale, based on Schiller’s poem of disillusionment and spiritual attainment.

“Liszt’s two-piano transcriptions of his tone poems are monumental in scope,” writes former Piano Quarterly publisher Robert Silverman in the CD notes. “These major works take on a whole new meaning when the musical palette is pared down to its essentials. The architecture and various melodic strands are clear to the ear . . . Yet the use of two pianos allows for great outpourings of sound — comparable to that of a full orchestra.”

“I’m not sure [Liszt] conceived the piano as having any limit of coloration,” Louise Mangos said in an interview with Fanfare’s James Reel. Reel echoed other reviewers in commenting, “The riveting Mangoses performances make a far better case for these works than the three integral orchestral cycles I have heard.”

Program Notes

Download Album BookletLiszt's Piano as Orchestra

Notes by Keith T. Johns

Central to an examination of Liszt’s aesthetic was his ability to make the piano sound like an orchestra. One of the earliest accounts of this exceptional ability appeared in The Scotsman (Edinburgh) discussing a performance of Liszt’s second piano concerto on January 21, 1841:

He seems to tear the very soul out of the instrument — he calls into requisition every sound and combination of sounds of which it is capable — to work it up as it were till it produces all the effects of the orchestra.

Liszt’s transcendence from piano virtuoso to composer of “serious” orchestral music sparked controversy among nineteenth century critics debating Zukunftsmusik (the music of the future). Such writers questioned how Liszt could synthesize what they considered two distinct compositional directions: that for orchestra, and that for piano. According to these critics, the most suspect element transplanted by Liszt was virtuosity. In a review of an all- Liszt program given in Berlin’s Singakademie in December 1855, the National-Zeitung printed:

Liszt’s symphonies and cantatas are displays of virtuosity that have only changed their setting: the keys of the piano have been exchanged for the choir and the orchestra.

That same concert touched off a long debate about the place of piano transcription. Otto Lindner, critic for Vossische Zeitung, maintained that the real test of an orchestral work was how well it sounded in piano reduction. Such a reduction, Lindner argued, would reveal the weaknesses in Liszt’s symphonic works. Hans von Bronsart, a tireless fighter for the Liszt cause, attacked Lindner’s assertions in a long article in the Berlin music journal Echo early in 1856. Bronsart illustrated his

discussion with an anecdote about a two-piano performance of Les Préludes in Weimar where a critic exclaimed: “If one thinks that Liszt can compose only for the piano, he should hear the piece for orchestra — then much becomes realized.”

The brilliant musicologist, Franz Brendel, also expounded upon this confusion of piano and orchestra as part of a long review of Liszt’s February 26, 1857 Gewandhaus concert:

It is said that Liszt plays the orchestra as earlier he played the piano. This proposition is at the same time both very correct and very false. When this is said it means that Liszt uses or misuses the orchestra with the aim of virtuosity. Rightly against that is the view that the orchestra and the forms of orchestral composition are no longer an objective power against which the artist stands in opposition but, on the contrary, both [the composition and the orchestra] fit all the impulses of the personality closely like a tight garment. That is the key to these compositions and, at the same time, to the orchestral statement and Liszt’s conducting. The tone poem is now the mirror and truest expression of individuality which is no more confined by the earlier boundaries. Individuality now roams free and unhindered.

From very early in his career, Liszt displayed an uncanny ability, as composer and performer, to extend the orchestral possibilities of the piano. For the piano always was Liszt’s “orchestra.” As recorded by Sir Charles Hallé, Liszt’s celebrated performance of Berlioz’s “March to the Scaffold” vividly demonstrates Liszt’s synthesis of piano, orchestra, composition, and performance:

At an orchestral concert given by Liszt and conducted by Berlioz, the “March to the Scaffold” from Symphonie fantastique, that most gorgeously instrumented piece, was performed, at the conclusion of which Liszt sat down and played his own arrangement for the piano alone, of the same movement, with an effect even surpassing that of the full orchestra, and creating an indescribable furore.

Liszt’s piano transcriptions of overtures by Berlioz and the Beethoven symphonies are testimony to his genius for transcribing orchestral music for the piano.

Liszt’s finest original keyboard works also present the piano-as-orchestra. Such works are by no means second-rate versions of what Liszt could or should have fully realized through the symphony orchestra. They instead represent Liszt’s unprecedented conception of the orchestra through the piano. Although the two-piano versions of Liszt’s Symphonic Poems appear to be transcriptions, they too should not be heard as secondary versions of that which Liszt in this case did write for full orchestra. These two-piano scores are unique creations: superlative examples of Liszt’s pianistic conception of the orchestra.

Pianist and writer, the late Keith T. Johns is author of the forthcoming book The Symphonic Poems of Franz Liszt (Pendragon Press).